Manuscript accepted on : 18-05-2025

Published online on: 10-06-2025

Plagiarism Check: Yes

Reviewed by: Dr. Makhabbah Jamilatun

Second Review by: Dr. Manita Paneri

Final Approval by: Dr. Ali Elshafei

Ningaraju Srikantaswamy and Manjula Ishwara Kalyani*

and Manjula Ishwara Kalyani*

Department of Studies and Research in Microbiology, Mangalore University, Jnana Kaveri Campus, Chikka Aluvara, Kodagu, India

Corresponding Author E-mail:manjuganesh7176@gmail.com

DOI : http://dx.doi.org/10.13005/bbra/3396

ABSTRACT: Endophytic bacteria found in medicinal plants are emerging as a possible source of novel bioactive chemicals with therapeutic promise, an investigation on the endophyte bacteria from the therapeutically valuable plant Hultholia mimosoides. Resulted in the molecular identification of potential endophyte bacteria belonging to the genus Pseudomonas spp and Bacillus subtilis. The 16S rRNA sequencing revealed a diverse group of bacteria, predominantly from the Pseudomonas genus, including Pseudomonas citronellolis PP843580, Pseudomonas mendocina PQ056994, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa PQ056923, alongside Bacillus subtilis PP795019. Ethyl acetate extracts of these strains were tested against six test pathogenic bacterial strains, including Escherichia coli ATCC8739, Salmonella typhimurium ATCC23564, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC23565, Klebsiella pneumonia ATCC9621, Bacillus cereus ATCC10876, and Proteus vulgaris ATCC13315. The well-diffusion assay revealed significant antimicrobial activity, particularly by Pseudomonas putida PP907914, which showed notable activity against all the test pathogens. Other strains also exhibited broad-spectrum activity, highlighting their potential to combat antibiotic-resistant pathogens. Among these, Pseudomonas citronellolis PP843580, has demonstrated a significant zone of inhibition with 16 mm against E. coli ATCC8739. These findings emphasize the symbiotic relationship between medicinal plants and their endophytic bacteria as a valuable source of novel bioactive compounds. The current study highlights the potential of endophytes as a source of medicine. Further exploration of the bioactive metabolites from these bacterial isolates could lead to the development of innovative therapeutics.

KEYWORDS: Antimicrobial; Bacillus; Hultholia mimosoides; Internal Transcribed Spacer; Pseudomonas

Download this article as:| Copy the following to cite this article: Srikantaswamy N, Kalyani M. I. Prominent Occurrence of Pseudomonas species as Endophytes in Hultholia mimosoides with Potential Antibacterial Activity. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(2). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Srikantaswamy N, Kalyani M. I. Prominent Occurrence of Pseudomonas species as Endophytes in Hultholia mimosoides with Potential Antibacterial Activity. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(2). Available from: https://bit.ly/4dWbyis |

Introduction

Endophytic bacterial composition in any medicinal plant has a major impact on its therapeutic potential. They contribute to maintaining the general physiology of the host plant by promoting growth, defending against pathogens, and enhancing tolerance to environmental stress. They are also involved in the synthesis of certain metabolites, including polyphenols, alkaloids and polysaccharides, which support mutualistic coexistence between the plant and endosymbiotic microbes. Although vast studies have analyzed the endophytic fungal association with plants, the contribution of endophytic bacteria to metabolic processes and plant sustenance cannot be neglected.

The requirement for novel and safe bioactive combinations to bring relief and comfort in human life is escalating. To fight new diseases brought on by contemporary lifestyles and declining environmental health, researchers are compelled to look into possible bioactive components. Medicinal plants are an important source of phytocompounds and act as a pool for numerous endophytic microorganisms.1 These microbes (bacteria or fungi) live in plant tissues without causing harm.2,3 Endophytic bacteria are a potent but unexplored source of phytochemicals. They are screened from a variety of plant parts, including leaves, stems, roots, flowers, and seeds.4 The ability of endophytes to produce metabolites originally known from their host plants, along with their potential to synthesize unique compounds, has drawn increasing research interest in their medicinal importance and minimal environmental impact.5,6 Diverse microbial endophytes inside plant tissues also support plant survival in extreme environments. Although free-living or associative microbes are ubiquitous in nature, there still remains a vast number of bacterial microbes that are still unidentified with potential as beneficial roles to play. Hence, the identification of microbial diversity is crucial for understanding their various roles and natural resources, such as ecological evolutionary relationships and their contributions to biodiversity. Identification protocols suggest that biotechnological uses aid in effective conservation and management strategies. Recently, advanced bacterial identification protocols suggest that molecular techniques, such as 16S rRNA gene sequencing, effectively prove to place unknown bacteria into their taxonomical nomenclature. There is a chance to identify both known and Unknown novel bacterial strains in the process of identification.7

Global health issues caused by pathogenic fungi and bacteria’s evolution of resistance to accessible antibiotics, the ineffectiveness of current antifungal and antibacterial agents against various fungal and bacterial infections, and the emergence of life-threatening viruses necessitate the urgent search for novel and effective antimicrobial agents.8 Antibiotic resistance is caused by a variety of causes, including inadequate hygiene, incorrect antibiotic administration, delayed infection diagnosis, and immunocompromised patients.9 In this context, developing alternate sources of antimicrobial chemicals is critical for combating the growing threat of drug-resistant bacteria, one of the most intriguing aspects of bacteria is their ability to create secondary metabolites with antibiotic properties, such as phenolics, terpenoids, and alkaloids. These compounds can suppress or kill pathogenic microbes, making endophytic bacteria valuable resources in the fight against antibiotic resistance.10 Endophytes are valuable as a “natural arsenal” of antibiotic adjuvants that can improve the effectiveness of traditional medications, as demonstrated by their ability to produce bioactive compounds capable of combating multidrug-resistant infections such as MRSA (Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus).11

Hultholia mimosoides, previously referred to as Caesalpinia mimosoides, is a small, spiky tropical tree or climbing shrub of the Fabaceae family. This plant is widely distributed across Asia. In Chikka Aluvara, Karnataka’s Kodagu region, residents consume the plant’s leaves and young twigs as a traditional appetizer known as “Arijinke Kudi“. Locals say H. mimosoides can help with fainting, dizziness, and flatulence. Furthermore, studies have shown that H. mimosoides leaf extract has anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, antioxidant, and antibacterial properties. The plant includes several phenolic compounds, including flavonoids and gallic acid, which are well-known for their strong antioxidant qualities.12 Based on this notion in the present study we focused our study on the medicinal plant H. mimosoides, growing in the region of Chikka Aluvara Kodagu as this plant is being consumed by the local communities as a side dish for curing ailments. We aimed to decipher any role played by the endophytic bacteria that could contribute to the medicinal properties of the plant.

Materials and Methods

Isolation of endophytic bacteria from H. mimosoides

Endophytic bacteria were isolated from the plant’s leaves and stem parts. The plant material was first washed with tap water to remove dust and debris, then chopped into small pieces in an aseptic environment using a sterilized blade. Surface sterilization was carried out by immersing the plant components in 70% ethanol for 1 minute, followed by submersion in a sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) solution for 30 seconds to 1 minute. The samples were rinsed with sterile distilled water for 1 minute and dried on filter paper. The surface-sterilized leaf and stem fragments were placed on Nutrient Agar (NA) plates and incubated at 37°C for 24 to 48 hours until bacterial colonies appeared. The pure cultures were stored on NA slants at 4°C with appropriate labelling and were subculture periodically for maintenance.13

Morphological and Biochemical characterization of endophytic bacterial isolates from H. mimosoides.

Endophytic bacterial isolates from the leaves and stem parts of H. mimosoides plants were characterized by both morphological and biochemical analyses. Morphological observations of the culture’s shape, color, elevation, and texture, and Gram staining were performed as part of the staining techniques. For biochemical characterization, tests such as IMViC and TSI agar were carried out to further characterize the bacterial cultures.

Molecular Identification of bacterial culture using 16s rRNA method

A volume of 500 µl of CTAB Extraction Buffer was added to the sample. The mixture was then homogenized and heated in a 60°C bath for 30 minutes. After the incubation period, the homogenate was subjected to vertical centrifugation for 5 min at 14000 x g. An equivalent amount of chloroform/isoamyl alcohol in a 24:1 ratio was added. Phase separation was achieved by vertexing the sample for 5 seconds and then centrifuged it at 14,000 x g for 5 minutes. The sample was stirred for 5 seconds, and then spun at 14,000 x g for 5 minutes to split the phases. The upper part of the water was moved to a new tube. 0.7 volume of cold isopropanol was added to precipitate the DNA, and then left to sit at -20°C overnight. Each time, 750 μl was added to the DNA column and spun at 12000 rpm for one minute. The speed was set to 12000 rpm and let it spin for one minute. Step 2 was done again with the wash brush. For two minutes, the DNA column was spun dry at 12000 rpm. The tube was set aside at room temperature for three minutes and spun at 12000 rpm for one minute. After adding 1 μl of RNase solution A, it was left to sit at 37°C for 30 minutes. Using agarose gel electrophoresis, the amount of DNA that was recovered was measured. The PCR conditions were set up with forward 5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′ reverse 5′-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′. To evaluate the amplification efficiency and produce multiplex PCR assays for DNA barcode primers, each PCR reaction consisted of 1µl of DNA template (25 ng), 2µl of 10X reaction buffer, 0.5µl of MgCl2 (50pM), 1µl of dNTPs mix (10mM), 1µl of forward primer (10pM), 1µl of reverse primer (10pM), 0.5µl of Taq polymerase (5 U/pi), and a final volume of 25µl. The final volume was adjusted to 25µl. The primers were standard primers used for amplifying the 16srRNA gene. Electrophoresis of the PCR product was performed using 0.8% agarose over TBE buffer at a voltage of 100 V. The endophytic fungi species were submitted to a sequencing for subsequent study. Analysis of the findings was conducted using the sequencing analysis software Mega11.

Extraction of endophytic bacteria

The isolated endophytic bacterial cultures were inoculated into 100 ml of NB (nutrient broth) medium and incubated at 370 C in the rotary incubator for 2 days. The fermentation broth was centrifuged at 10000 rpm for 20 min at 40 C, mixed with an equal volume of ethyl acetate. The ethyl acetate layer was collected using a separating funnel and dried. Then, the extracts were dissolved in DMSO (Dimethyl Sulfoxide) for anti-microbial activity.16

Antimicrobial activity

The antibacterial activity of the crude bacterial ethyl acetate extracts was tested by the well-diffusion technique. The bacterial pathogens were spread to the Nutrient agar contained in 90 mm petri plates with the help of a L-shaped glass rod. Using a cork borer, 9 mm-diameter wells were made and inoculated with 100 µl (10 mg/mL) of crude endophytic fungal extracts to the agar wells. Chloramphenicol, a common antibiotic, was employed as the positive control (50 µl – 1mg/ml), as a negative control, DMSO was used. For 24 hours, the plates were incubated at 370 C. After 24 hours of incubation, the inhibitory zone’s width was measured.13

Results

Isolation of endophytic bacteria

Endophytic bacteria were isolated from the stem and leaf parts of the H. mimosoides plant using NA (nutrient agar) medium. A total of 40 segments were placed from both the stem and leaves of the H. mimosoides plant. Upon 2 days of growth on NA medium, endophytic bacterial cultures were observed. The colonization rates of the endophytic bacteria isolates were 82.7% from the leaf segments and approximately 80% from the stem segments. Fourteen endophytic bacterial cultures were isolated from both parts of the plant and further subjected to biochemical and morphological characterizations.

Microscopic and Biochemical characterization of endophytic bacteria

Fourteen endophyte bacterial isolates were subjected to microscopic and biochemical characterizations. Based on similarities in morphological and biochemical characterizations seven endophytic bacterial isolates were chosen and subcultured. Preliminary identification was based on morphological differences and distinct biochemical profiles, and isolates of bacteria were allocated a unique code; such as HB-1, HB-2, HB-3, HB-4, HB-5, HB-6, and HB-7 (HB – Hulotholia bacteria).

The biochemical tests such as Indole, Methyl Red-Voges Proskauer (MR-VP), Citrate, Glucose, Sucrose, and Lactose fermentation were negative for bacterial isolate HB-1, whereas Catalase, Oxidase, and Urease activities were positive, it was determined to be positive bacilli after staining and microscopic observation. These characteristics were found to be similarity to the bacterial species of Micrococcus spp and Bacillus spp. Isolate HB-2 exhibited negative in Indole, MR-VP, and Oxidase tests and positive results for Citrate, Glucose, Sucrose, Lactose, catalase, and oxidase tests. Gelatinase and Urease tests were observed that showed negative results. It was found to be negative bacilli upon gram staining. These characteristics according to Bergey’s manual showed Pseudomonas and Aeromonas spp.

Similarly, isolates HB-3, HB-4, and HB-5 exhibited consistent results, the isolates showed negative for indole and MR-VP, here HB-3 and HB-4 both showed positive results for citrate and glucose, and HB-5 showed negative results in the glucose test. both isolates HB-3 and HB4 revealed a negative for sucrose, lactose, and gas production in the TSI test but BH-5 showed positive results, and all three isolates showed positive in catalase, and oxidase and negative for urease and gelatinase these observations indicated the characteristics of genera Pseudomonas spp. Isolate HB-6 test negative for indole and MR-VP and positive for urease, citrate, and catalase, the TSI slant demonstrated a positive glucose fermentation result and was observed to be negative bacilli, these observations, correlating with their biochemical properties, suggest that the isolates are quite similar to Pseudomonas species. Isolate HB-7 showed the characteristics of Klebsiella spp, Pseudomonas spp, and Enterobacter spp such as, negative for indole and citrate, but positive for MR-VP, it showed positive for glucose fermentation, negative for sucrose, lactose, and gas production in the TSI test, this isolate was catalase-positive, oxidase-negative, and positive for gelatinase and urease, this isolated could be characterization as negative bacilli. All the above observations were updated in Table 1 and Figure 1.

Table 1: Biochemical and staining characteristics of endophytic bacteria.

| SL.No | Isolates | IMViC

|

TSI | Catalase | Oxidase | Gelatin | Urease | Staining observation | |||||

| Indole | MR-VP | Citrate | Glucose | Sucrose | Lactose | Gas | |||||||

| 1 | HB-1 | – | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | + | – | – | Positive bacilli |

| 2 | HB-2 | – | – | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | – | – | Negative bacilli |

| 3 | HB-3 | – | – | + | + | – | – | + | + | + | – | – | Negative bacilli |

| 4 | HB-4 | – | – | + | + | – | – | + | + | + | – | – | Negative bacilli |

| 5 | HB-5 | – | – | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | – | – | Negative bacilli |

| 6 | HB-6 | – | – | + | + | – | – | + | + | + | – | – | Negative bacilli |

| 7 | HB-7 | – | + | – | – | + | + | + | + | + | – | – | Negative bacilli |

|

Figure 1: Morphological and microscopically characteristics of the endophytic bacteria from H. mimosoides:- HB1- irregular form, elevation is flat, margin showing Undulate and cream color colony and microscopic characteristics is positive bacilli; |

Molecular identification of endophytic bacteria

Molecular identification is crucial for accurately classifying the microorganisms and understanding their beneficial roles in plant growth, stress tolerance, and ecological interactions. The identification also aid for their biotechnological potential and biomedical applications. In this study, the biochemical and gram staining results lead to the identification of isolates belonging to the genera of Micrococcus, Staphylococcus, Klebsiella , Enterobacter, Pseudomonas, Klebsiella and Enterobacter. The ITS sequencing protocol was followed for taxonomical classification of the bacteria.

The endophytic strains were identified by 16S rRNA sequencing using the 27F and 1492R universal primers. The 16S rRNA sequences of the endophytes were compared with those of other bacterial sequences by way of BLAST. The molecular identification of the bacterial cultures revealed a diverse group of species, predominantly from the Pseudomonas genus. Endophytic bacterial isolate HB-1 was determined to be Bacillus subtilis based on 98.29% sequence identity. With a 98.18% identity rate, isolate HB-2 was determined to be Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Pseudomonas mendocina was matched by isolate HB-3 with a high identity of 99.9%. With a 99.49% match, isolate HB-4 was determined to be Pseudomonas citronellolis, and with a 98.77% identity, isolate HB-5 was determined to be Pseudomonas putida. With 99.29% sequence identity, isolate HB-6 was verified as Pseudomonas flexibilis, and with 99.42% match, isolate HB-7 was determined to be Pseudomonas hunanensis. The high percentage of identity demonstrated in these results, which ranges from 98.18% to 99.9%, validates the accurate determination of the isolated strains. The results illustrate the variety within this genus by demonstrating a majority of Pseudomonas species, one Bacillus species was identified among the selected isolates. All the identified bacterial sequences were submitted to GenBank and obtained the accession numbers mentioned in Table 2. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the partial 16S rRNA sequences of the putative endophytic bacterial isolates and representative bacterial type strains of related taxa generated by the neighbor-joining method is presented in Figure 2.

Table 2: Identification of endophytic bacteria with accession number.

| Sl no | Endophytic bacterial Culture code | Molecular identification | Microscopic obervation | Gen bank accession number |

| 1 | HB-1 | Bacillus subtilis | Positive bacilli | PP795019 |

| 2 | HB-2 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Negative bacilli | PQ056923 |

| 3 | HB-3 | Pseudomonas mendocina | Negative bacilli | PQ056994 |

| 4 | HB-4 | Pseudomonas citronellolis | Negative bacilli | PP843580 |

| 5 | HB-5 | Pseudomonas putida | Negative bacilli | PP907914 |

| 6 | HB-6 | Pseudomonas flexibilis | Negative bacilli | PP907969 |

| 7 | HB-7 | Pseudomonas hunanensis | Negative bacilli | PP908387 |

*HB- Hultholia Bacteria

|

Figure 2: Phylogenetic tree of endophytic bacteria isolated from H. mimosoides based on ITS sequence. The tree was constructed with the maximum Likelihood method in MEGA 11 using default parameters, and bootstrap values were calculated after 1,000 replications. |

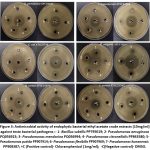

Antimicrobial activity of endophytic bacteria from H. mimosoides

In this study, the well-diffusion method assessed the antibacterial activity of ethyl acetate crude extracts of endophytic bacteria against six test bacterial pathogens. When compared with the positive control, chloramphenicol (1mg/ml), nearly all of the crude extracts demonstrated antibacterial activity against the test bacterial pathogens. The antimicrobial effectiveness of the various bacterial strains was assessed by measuring the zones of inhibition expressed in millimeters (mm), against the selected pathogens: Klebsiella pneumonia ATCC9621, Salmonella typhimurium ATCC23564, Escherichia coli ATCC8739, Proteus vulgaris ATCC13315, Bacillus cereus ATCC10876, and Staphylococcus aureus ATCC23565. Bacillus subtilis PP795019 showed minimal antibacterial activity against S. typhimurium ATCC23564, P. vulgaris ATCC13315, S. aureus ATCC23565, or K. pneumonia ATCC9621. However, it did show modest activity against E. coli ATCC8739, with an inhibition zone of 6 mm, and B. cereus ATCC10876, with a 5 mm inhibition zone. P. aeruginosa PQ056923 demonstrated broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity, showing a 13 mm zone of inhibition against K. pneumonia ATCC9621 and E. coli ATCC8739. Additionally, it inhibited B. cereus ATCC10876 with a 9 mm zone of inhibition, P. vulgaris ATCC13315 with a 10 mm zone, and S. typhimurium ATCC23564 with a 10 mm zone. No detectable inhibition of S. aureus ATCC23565 was found. P. mendocina PQ056994 exhibited inhibition zones of 11 mm and 15 mm, respectively, and was mostly active against E. coli ATCC8739 and B. cereus ATCC10876. Furthermore, it showed no inhibition against S. typhimurium ATCC23564, P. vulgaris ATCC13315, and S. aureus ATCC23565, but a 9 mm zone of inhibition against K. pneumonia ATCC9621.

Strong antibacterial activity against S. typhimurium ATCC23564 (12 mm) and E. coli ATCC8739 (16 mm) demonstrated the effectiveness of P. citronellolis PP843580. It also showed moderate inhibition against K. pneumonia ATCC9621 (6 mm), P. vulgaris ATCC13315 (11 mm), and B. cereus ATCC10876 (12 mm). However, it exhibited no activity against Staphylococcus aureus ATCC23565. P. putida PP907914 displayed weak antimicrobial effects across the board, with inhibition zones of 6 mm for K. pneumonia ATCC9621 and S. typhimurium ATCC23564, 5 mm for E. coli ATCC8739, 9 mm for P. vulgaris ATCC13315, 2 mm for B. cereus ATCC10876, and 4 mm for S. aureus ATCC23565. Low antibacterial activity was demonstrated by P. flexibilis PP907969, which produced modest inhibition zones of 2 mm for E. coli ATCC8739 and K. pneumonia ATCC9621, 8 mm for S. typhimurium ATCC23564, 9 mm for P. vulgaris ATCC13315, and 46 mm for S. aureus ATCC23565. There was no evidence of inhibition against Bacillus cereus ATCC10876. P. hunanensis PP908387 exhibited minimal activity, with slight inhibition against K. pneumonia ATCC9621 (2 mm), S. typhimurium ATCC23564 (4 mm), E. coli ATCC8739 (4 mm), P. vulgaris ATCC13315 (8 mm), and S. aureus ATCC23565 (4 mm). There was no observed activity against B. cereus ATCC10876. Overall, P.citronellolis PP843580 showed effective antimicrobial activity with the highest zone of inhibition against E.coli ATCC8739 (16mm) Figure 3 and Table 3.

|

Figure 3: Antimicrobial activity of endophytic bacterial ethyl acetate crude extracts (10mg/ml) against teste bacterial pathogens: |

Table 3: Antimicrobial activity from bacterial ethyle acetate extract

Sl No |

Endophytic bacteria names | Bacterial pathogens (zone of inhibition in mm) | |||||

| K. pneumonia ATCC9621 | S.typhemurum ATCC23564 | E.coli ATCC8739 | P. vulgaris ATCC13315 | B. cereus ATCC10876 | S. aureus ATCC23565 | ||

| 1 | B.subtilis PP795019 | – | – | 6 | 5 | – | |

| 2 | P.aeruginosa PQ056923 | 13 | 10 | 13 | 10 | 9 | – |

| 3 | P.mendocina PQ056994 | 9 | – | 11 | – | 15 | – |

| 4 | P.citronellolis PP843580 | 6 | 12 | 16 | 11 | 12 | – |

| 5 | P.putida PP907914 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 9 | 2 | 4 |

| 6 | P.flexibilis PP907969 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 9 | – | 6 |

| 7 | P.hunanensis PP908387 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 8 | – | 4 |

Discussion

Endophytic and plant growth-promoting bacteria are essential for improving nodule formation, nutrient uptake, and plant growth in a variety of plants. Microorganisms’ biochemical characterization is crucial for revealing information on both their provisional identification and their roles. Recently, new areas of investigation have emerged as a result of molecular and genetic advances in medicinal plant research. Our study was to discover bacterial endophytes in H. mimosoides’ leaves and stem parts. According to Bergey’s Manual, the biochemical and staining analysis revealed that the isolated endophytic bacteria have shown the characteristics of Aeromonas sp, Pseudomonas sp, Bacillus sp, Micrococcus sp, and Enterobacter sp.

The molecular identification of isolates HB-1 to HB-7 provided precise species-level classification, complementing and refining the biochemical and Gram staining observations. HB-1 was identified as Bacillus subtilis, aligning well with its biochemical profile of Gram-positive bacilli, catalase positivity, and urease activity, confirming the genus Bacillus. HB2, identified as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, showed discrepancies with biochemical results, highlighting the importance of molecular methods for accurate identification. HB3 (P. mendocina), HB-4 (P. citronellolis), HB-5 (P. putida), and HB6 (P. flexibilis) exhibited consistent results between biochemical tests and molecular identification, confirming them as Pseudomonas species. HB-7, identified as P. hunanensis, showed variations in biochemical traits but was confirmed through molecular analysis, demonstrating the variability in phenotypic expression. While biochemical tests provided useful preliminary insights at the genus level, molecular methods ensured accurate species-level identification, particularly for isolates with atypical biochemical profiles. This integrated approach scores its value in bacterial characterization. Molecular methods are essential for precise species-level resolution, whereas biochemical methods offer a helpful preliminary assessment. The dominance of Pseudomonas species suggests their potential ecological significance as plant-associated bacteria.

The endophytic bacteria isolated from medicinal plants, such as Berberis aristata, had characteristics including citrate consumption and urease, which are crucial for nitrogen metabolism and improving the plant’s capacity to absorb vital nutrients. Their symbiotic associations with medicinal plants, which support plant growth in soil low in nutrients, are largely attributed to these biochemical properties.14 Studies on endophytic Bacillus species isolated from therapeutic plants such as Trigonella foenum-graecum have demonstrated promising outcomes for glucose fermentation, urease and catalase activities common metabolic features that support plant development. These endophytic bacteria frequently have important functions in the generation of enzymes, nitrogen fixation, and stress-resilient host plant health. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that Bacillus endophytes contain gelatinase activity, a characteristic that helps break down proteins in the plant’s surroundings and promotes nutrient cycling.15 The bacterial cultures isolated in this study exhibited important biochemical characteristics with plant-beneficial endophytes, including the use of citrate, urease, glucose fermentation, catalase, and gelatinase activity. These metabolic characteristics in the isolated bacterial cultures suggest possible functions in nutrient cycling and promoting plant growth.

A study from Aerva javanica, 16S rRNA sequencing identified bacterial endophytes, including Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas fluorescens, Micrococcus luteus, Enterobacter cloacae, and Delftia tsuruhatensis. These bacteria enhance the health and resilience of plants by producing indole acetic acid (IAA), phosphate solubilization, and stress tolerance, among other characteristics that promote plant growth.16 Significant novel details about the diversity and functions of bacteria have been made possible by the molecular identification of endophytic bacteria from medicinal plants using 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Bacillus and Pseudomonas, for instance, were found in Catharanthus roseus, demonstrating their capacity to promote plant development and therapeutic qualities.17 A variety of bacterial communities, including Firmicutes and Actinobacteria, were discovered in Curcuma longa. Several strains of these bacteria were connected to the enhancement of plant growth, which may have an impact on the plant’s potential as a medicine.18

The antimicrobial activity of endophytic bacteria from medicinal plants is particularly important to combat the developing issue of antimicrobial resistance. These microorganisms frequently generate new bioactive compounds that can improve the effectiveness of current therapies or act as new antibiotics. Additionally, capacity of endophytic bacteria to colonize plant tissues without endangering the host may provide environmentally acceptable and sustainable methods of treating disorders in humans as well as plants, in addition to exhibiting antibacterial qualities, endophytic bacteria isolated from Achillea species also stimulated plant development, indicating potential advantages for both therapeutic and agricultural uses. Human pathogens, including both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, are test against extracts or metabolites produced by these bacteria.19 For instance, the endophytic bacteria isolated from Citrus limon exhibited strong antimicrobial activity against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus.20 Another study on Tamarix aphylla revealed that endophytic strains had broad-spectrum activity, inhibiting the growth of pathogenic bacteria and fungi.21

In this investigation, the isolated endophytic ethyl acetate extract was test for antibacterial efficacy against six pathogenic microorganisms. The results showed that all endophytic bacterial crude extracts had considerable antibacterial activity against the test pathogens.

Notably, P. putida PP907914 was active against all test pathogens and all endophytic bacterial extracts were found to have high efficacy against Escherichia coli. P. aeruginosa (PQ056923) and P. citronellolis (PP843580) had the largest zones of inhibition at 13 mm and 16 mm, respectively but the B. subtilis PP795019 extract showed activity against two pathogens E. coli and B. cereus ATCC10876 as detailed in results part. These findings suggest that Pseudomonas sp. from the medicinal plant H. mimosoides are potential endophytic bacteria with promising antimicrobial properties.

The production of bioactive compounds with antibacterial, antioxidant, and anticancer effects is a well-known characteristic of endophytic Pseudomonas species. These bacteria produce a variety of metabolites with potent biological activity, such as terpenoids, flavonoids, and alkaloids. Pseudomonas aeruginosa inhibits fungal pathogens like Fusarium oxysporum through Pyrrolo [1,2-a]pyrazine-1,4-dione, a potent antifungal compound.22 Its secondary metabolites, including pyocyanin, rhamnolipids, and phenazines, show strong efficacy against resistant bacteria including Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli.23 Other compounds, including nonadecanamide and pyrrolo derivatives, show inhibition zones up to 15.28 mm against E. coli.24 Extracts from medicinal plant-associated strains have also been shown to have antioxidant activity, with cytotoxic effects on HeLa cells.25 The therapeutic potential of Pseudomonas metabolites is further highlighted by solvent-extracted metabolites like flavonoids and aminoglycosides, which present encouraging remedies against infections that are resistant to several drugs.

This study’s findings showed that ethyl acetate extracts of endophytic bacterial strains have significant antimicrobial activity against six test bacterial pathogens. Ethyl acetate is known to extract secondary metabolites, many of which possess antibacterial properties. Because endophytic bacteria produce metabolites that shield their host plants against infections, they are a potential source of novel bioactive compounds. The broad-spectrum efficacy seen against a range of bacterial illnesses indicates that these extracts are capable of combating both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. This suggests that the active components could be useful alternatives to conventional antibiotics.

Conclusion

This study successfully demonstrated the isolation of bacterial endophytes from the medicinal plant H. mimosoides, with seven different bacterial isolates identified and molecularly characterized. Ethyl acetate extracts from all seven isolates showed significant antibacterial activity, with Pseudomonas species having the most promise as manufacturers of bioactive antimicrobial chemicals. These findings suggest that Pseudomonas spp. could serve as promising candidates for the development of new antibacterial agents. However, more in-depth research is required to properly investigate and evaluate their therapeutic potential.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the Department of Studies and Research in Microbiology, Mangalore University, Jnana Kaveri Campus, P. G. Centre, Chikka Aluvara, Kodagu and the Molecular Research Laboratory (SERB, Govt. of India 2017-2022, CISEE VGST Govt. of Karnataka 2019-2023) for helping to conduct this research work for granting the Ph.D. research work.

Funding Sources

Mangalore University SC-ST fellowship (Fellowship sanction No: MU/SCTCell/RF/C.R5/2021-22/SCT-1. Dated: 13-06-2022).

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

This statement does not apply to this article.

Ethics Statement

This research did not involve human participants, animal subjects, or any material that requires ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not involve human participants, and therefore, informed consent was not required.

Clinical Trial Registration

This research does not involve any clinical trials.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

Not Applicable

Author Contributions

Ningaraju Srikantaswamy: Performed all of the tests.

Manjula Ishwara Kalyani: Supervised and guided for writing the publication.

References

- Ghosh S, Bhagwat T, Webster TJ. Endophytic Microbiomes and Their Plant Growth-Promoting Attributes for Plant Health. In: Yadav AN, Singh J, Singh C, Yadav N, eds. Current Trends in Microbial Biotechnology for Sustainable Agriculture. Springer; 2021:245-278. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-6949-4_11

CrossRef - Dastogeer KMG, Tumpa FH, Sultana A, Akter MA, Chakraborty A. Plant microbiome–an account of the factors that shape community composition and diversity. Curr Plant Biol. 2020;23:100161. doi:10.1016/j.cpb.2020.100161

CrossRef - Orozco-Mosqueda Ma del C, Santoyo G. Plant-microbial endophytes interactions: Scrutinizing their beneficial mechanisms from genomic explorations. Curr Plant Biol. 2021;25:100189. doi:10.1016/j.cpb.2020.100189

CrossRef - Bacterial Endophytes from Moringa oleifera Leaves as a Promising Source for Bioactive Compounds. Accessed May 6, 2025. https://www.mdpi.com/2297-8739/10/7/395

CrossRef - Petrini, O. (1991) Fungal Endophytes of Tree Leaves. In Andrews, J.H. and Hirano, S.S., Eds., Microbial Ecology of Leaves, Springer-Verlag, New York, 179-197. – References – Scientific Research Publishing. Accessed February 28, 2025. https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=2576095

CrossRef - Urs D, Giresha AS, Tejaswini HK, Prabhakar BT, Dharmappa KK. Edible Foliage Endophytes and Their Natural Metabolites: Significance in Supporting Human Health. In: Natural Bioactives from the Endophytes of Medicinal Plants. CRC Press; 2025.

CrossRef - Janda JM. The Molecular Technology Revolution and Bacterial Identification: Unexpected Consequences for Clinical Microbiologists. Clin Microbiol Newsl. 2023;45(6):47-54. doi:10.1016/j.clinmicnews.2023.03.001

CrossRef - Gauba A, Rahman KM. Evaluation of Antibiotic Resistance Mechanisms in Gram-Negative Bacteria. Antibiotics. 2023;12(11):1590. doi:10.3390/antibiotics12111590

CrossRef - Alara JA, Alara OR. An Overview of the Global Alarming Increase of Multiple Drug Resistant: A Major Challenge in Clinical Diagnosis. Infect Disord – Drug Targets Former Curr Drug Targets – Infect Disord. 2024;24(3):26-42. doi:10.2174/1871526523666230725103902

CrossRef - Nisa S, Khan N, Shah W, et al. Identification and Bioactivities of Two Endophytic Fungi Fusarium fujikuroi and Aspergillus tubingensis from Foliar Parts of Debregeasia salicifolia. Arab J Sci Eng. 2020;45(6):4477-4487. doi:10.1007/s13369-020-04454-1

CrossRef - Moussa AY. Endophytes: a uniquely tailored source of potential antibiotic adjuvants. Arch Microbiol. 2024;206(5):207. doi:10.1007/s00203-024-03891-y

CrossRef - Feng R, Xu JX, Luan XY, et al. Chemical constituents with antioxidant activity from the branches and leaves of Hultholia mimosoides. Phytochemistry. 2024;223:114131. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2024.114131

CrossRef - Gowthami GA, Das S, Karthik Y, Manjula IK. Study of antibacterial, anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic potential of the cell extracts of endophytic fungi and bacteria isolated from Pajanelia longifolia (Willd.) K. Schuman. Plant Sci Today. 2021;8(3):501-508. doi:10.14719/pst.2021.8.3.1104

CrossRef - Isolation and characterization of endophytic bacteria from medicinal plants (Berberis aristata and Xanthium strumarium)…. Accessed March 4, 2025. http://ouci.dntb.gov.ua/en/works/4YZXWgal/

- Frontiers | Bacillus subtilis ER-08, a multifunctional plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium, promotes the growth of fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum L.) plants under salt and drought stress. Accessed May 6, 2025.https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/microbiology/articles/ 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1208743/full

- Some Direct and Indirect Mechanisms of Endophytic Bacteria That Associated with The Medicinal Plant Areva javanica from Shada Al-Asfal Mountain. SciSpace – Paper. doi:10.20944/preprints 202407.0145.v1

CrossRef - Bhuvaneswari S. Evaluation of In vitro Antibacterial Activity of Endophytic Bacteria Isolated from Catharanthus roseus. SBV J Basic Clin Appl Health Sci. 2024;7(2):42. doi:10.4103/SBVJ.SBVJ_7_24

CrossRef - Frontiers | Rhizobacterial mediated interactions in Curcuma longa for plant growth and enhanced crop productivity: a systematic review. Accessed May 6, 2025.https://www.frontiersin.org/ journals/ plant-science/articles/10.3389/fpls.2023.1231676/full

- Secondary Metabolites Produced by Plant Growth-Promoting Bacte… Accessed May 6, 2025. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/34189

- Buragohain T, Dey P, Osborne WJ. In vitro studies on the inhibition of microbial pathogens by PPDHMP synthesized by Bacillus sp.; an endophyte of Citrus limon (Kaji nemu). Food Biosci. 2023;55:103003. doi:10.1016/j.fbio.2023.103003

CrossRef - Yadav G, Meena M. Bioprospecting of endophytes in medicinal plants of Thar Desert: An attractive resource for biopharmaceuticals. Biotechnol Rep. 2021;30:e00629. doi:10.1016/j.btre.2021.e00629

CrossRef - Drożdżyński P, Rutkowska N, Rodziewicz M, Marchut-Mikołajczyk O. Bioactive Compounds Produced by Endophytic Bacteria and Their Plant Hosts—An Insight into the World of Chosen Herbaceous Ruderal Plants in Central Europe. Molecules. 2024;29(18):4456. doi:10.3390/molecules29184456

CrossRef - Elfadadny A, Ragab RF, AlHarbi M, et al. Antimicrobial resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: navigating clinical impacts, current resistance trends, and innovations in breaking therapies. Front Microbiol. 2024;15. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2024.1374466

CrossRef - Neve RL, Giedraitis E, Akbari MS, Cohen S, Phelan VV. Secondary metabolite profiling of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates reveals rare genomic traits. mSystems. 2024;9(5):e00339. doi:10.1128/msystems.00339-24

CrossRef - Mombeshora M, Mukanganyama S. Antibacterial activities, proposed mode of action and cytotoxicity of leaf extracts from Triumfetta welwitschii against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2019;19:315. doi:10.1186/s12906-019-2713-3

CrossRef

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.