Manuscript accepted on : 15-04-2025

Published online on: 06-05-2025

Plagiarism Check: Yes

Reviewed by: Dr. Rishee K Kalaria

Second Review by: Dr. Ankur Vashi

Final Approval by: Dr. Wagih Ghannam

Numerical Modelling of Alveolar Gas Exchange to Calculate the Fractional Pressure of Carbon Monoxide

Nirali Patel* and Kaushal Patel

and Kaushal Patel

Department of Mathematics, Veer Narmad South Gujarat University, Surat, India.

Corresponding Author E-mail: niralipatel2038@gmail.com

DOI : http://dx.doi.org/10.13005/bbra/3397

ABSTRACT: The primary function of the human respiratory system is gas exchange, encompassing the exchange of various gases. This work focuses on analyzing the transport of carbon monoxide ( ) within the human body. We have divided the human body into two compartments: alveolar and pulmonary capillaries. A mathematical model is required to derive the fractional pressure of carbon monoxide from the air. In this work, we study the lung compartment model for carbon monoxide exchange during human respiration. Our objective is to create a classical differential model for the volume of carbon monoxide present in the alveolar and capillary compartments of the lungs. We also numerically solve the concentration of carbon monoxide in the hemoglobin equation and estimate the carbon dioxide diffusing capacity under various conditions.

KEYWORDS: Carbon monoxide; Concertation; Fractional Pressure; Gas Exchange; Mathematical Model; Volume

Download this article as:| Copy the following to cite this article: Patel N, Patel K. Numerical Modelling of Alveolar Gas Exchange to Calculate the Fractional Pressure of Carbon Monoxide. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(2). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Patel N, Patel K. Numerical Modelling of Alveolar Gas Exchange to Calculate the Fractional Pressure of Carbon Monoxide. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(2). Available from: https://bit.ly/4m1OQcf |

Introduction

The gas carbon monoxide (Co) has no color, no smell, and no taste. Accidental poisoning deaths have been the main cause. It also makes a significant contribution to atmospheric pollutants arising from both natural sources and human activities. Burning fossil fuels (coal, oil, and natural gas) is the main source of Co, and motorized vehicles are the main contributors. Also, the human body produces Co in tiny amounts.2,3

Supplying oxygen (O2) to the tissues and removing the carbon dioxide ( CO2) they produce are the primary functions of the human respiratory system. The blood carries the greatest amount of O2 and reacts with hemoglobin molecules.4,5 Although carbon monoxide (Co) is delivered similarly to oxygen (O2), its affinity for hemoglobin is more than 200 times greater. The blood carrying capacity to transport O2 reduces when Co is present. Consequently, high concentrations of Co can lead the tissues to become oxygen-deficient.6

The association between hemoglobin and carbon monoxide (Co), known as concentration of carbon monoxide in the hemoglobin, indicates the amount of hemoglobin that has reacted with Co7. Which is evaluated by blood analysis or exhaled air, is used to relate the effects of Co in the human body.8,9

The fractional pressures in the alveoli determine in which gases such as O2, CO2, and Co are exchange in the blood by the pulmonary capillaries and the alveolar air. It is easy to calculate the fractional pressures or concentrations of these gases in inspired air.10,11 However, it often challenging to calculate the corresponding fractional pressures in the alveoli as a function of exposure time.12,13

Raffe and Marc utilized the ventilation-perfusion equation to model gas exchange in the lungs. Factors such as the fractional pressure of inspired air, the ventilation-perfusion ratio, several factors affect alveolar fractional pressure, including the gas exchange ratio and the intake and release of gases in the pulmonary circulation.1-14

Olszowka and Farhi developed a model to calculate the fractional pressure of gases in alveolar air based on the corresponding pressure in inspired air.1-15 West and Wagner also created a computer application for this method.16

“Tsega and Katiya proposed that for the diffusion of gases between capillary blood and alveolar air, the pressure differential between the capillary blood and the alveolar end is negligible for all gases1,17. Motterlini and Roberto introduced a model for calculating the alveolar fractional pressure of CO, as its mean value varies unlike O₂ and CO₂, and diffusion limits the amount of CO transport in the lungs.1-18

“Calculating the alveolar fractional pressure of CO (PA CO) necessitates the development of a mathematical model to determine concentration of carbon monoxide levels in blood based on exposure time and atmospheric CO concentration.19

The model considers factors such as the blood flow rate, lung diffusion capacity, inspired and expired airflow rates, atmospheric CO concentration, and the non-linear CO dissociation curve. Additionally, it explains the effects of blood O2 on the CO dissociation curve.20, 21

These facts were used by Filley and MacIntosh to calculate the pulmonary diffusing capacity of people during steady-state CO absorption during at rest. They created a clinically useful technique for figuring out the diffusing capacity for CO during exercise that circumvents the difficulties of direct alveolar gas sampling. The results of research on a group of healthy participants who breathed 0.1 percent CO in the air both at rest and while exercising was presented using this technique.22,23

Studies have shown that PACO increases exponentially over time and eventually reaches an asymptotic value for a given atmospheric CO concentration. As atmosphere CO concentration rises, alveolar PCO increases further. Concentration of carbon monoxide levels in the hemoglobin as a function of exposure time can also be measured with this model, and the results are comparable to the values obtained experimentally and using the CFK equation.24,25

Materials and Methods

In this work, we present a model that predicts the alveolar fractional pressure of CO based on the corresponding atmospheric concentration.

|

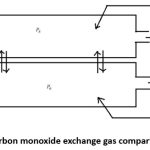

Figure 1: Carbon monoxide exchange gas compartment model. |

According to this model, the liquids and gases within the compartments are uniform. The time variations of each compartment’s gas composition are described by the ordinary differential equations, with one equation for carbon monoxide gas and one for each compartment.

The model comprises two compartments. Inspired air enters the first compartment, representing the lungs, at body temperature and pressure, with a flow rate of QI. Under BTPS conditions, the air is saturated with water vapor and exits as expired air with a flow rate of QE. Venous blood enters the second compartment, representing the vascular system in the lungs, at a flow rate of Qb and exits as arterial blood, maintaining the same flow rate, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

The blood-gas barrier separates these compartments and diffusion through them to communicate with each other. It is considered that the gas in both compartments is well mixed.

In the well-mixed alveolar compartment, let PI represent the fractional pressure of a gas in the humidified inspired air, and PA be the corresponding fractional pressure of the gas in the alveolar air. As a result, the expired air leaves the compartment with the same fractional pressure. The fractional pressures in the pulmonary capillary and venous blood compartments are denoted by Pa and Pv, respectively

The rate at which the alveolar compartment’s air lost/gained gas is

Here, β represents the conversion of air flow rate (QE) from BTPS conditions to standard temperature, pressure, and dry conditions (STPD). The barometric pressure is denoted by PB.

The rate at which the amount of gas gained/ lost in the blood compartment is,

![]()

A portion of the gas is physically dissolved in plasma and transported by the blood, while the remainder combines with hemoglobin, depending on the gas’s nature. We acknowledge the potential significance of the gas’s non-equilibrium chemical kinetics with hemoglobin.

We assume that the chemical reaction between the gas and hemoglobin is in equilibrium. The following defines the total gas content (C) in the blood.:

![]()

where P represents the fractional pressure of the gas in the blood, αb denotes the solubility of the gas in the blood, S(P) is the saturation function dependent on P, and N is the blood’s carrying capacity for the gas.

The rate at which gas diffuses across the blood-gas barrier is defined as follows:

![]()

The alveolar compartment serves as the initial interface between the human body and external air. It contains the gas within the lung alveoli and is traversed by alveolar ventilation flow.

Gas transfer by diffusion across the respiratory membrane to the pulmonary capillary compartment is another important process in the alveolar compartment. The subsequent equations represent entire process, taking into account the diffusion coefficient from STPD to BTPS.

At body temperature, the gas in the alveoli is always saturated with water vapor. Measurements at body temperature and pressure saturated (BTPS) conditions are used to determine the fractional pressure of alveolar gas. However, the conventional method to measure blood gas concentration is at standard temperature and pressure, dry (STPD) conditions.

The amount of gas present in the alveolar compartment,

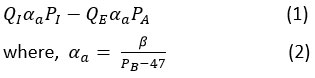

Differential equation derived of eq. (6) we get,

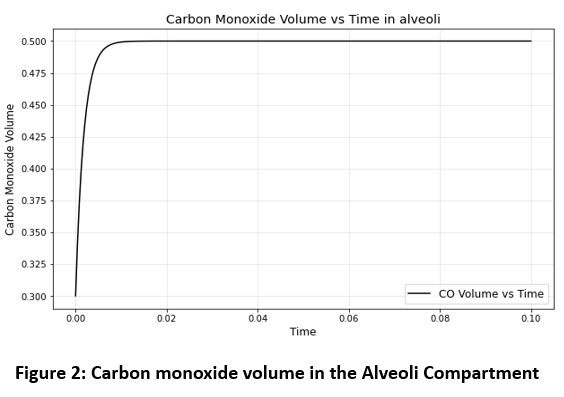

For equation (7) derived the graph for the carbon monoxide volume in alveoli compartment, it depends on the carbon monoxide partial pressure in the alveoli.

|

Figure 2: Carbon monoxide volume in the Alveoli Compartment |

A series of compartments represents the pulmonary capillaries. After passing through the respiratory membrane and entering the next pulmonary compartment, venous blood exchanges gases with the alveolar compartment.

The rate at which the venous compartment’s amount of gas changes is

![]()

where the gas volume in venous blood is represented by Vv

Carbon monoxide has a greater affinity for hemoglobin compared to O₂. The maximum amount of Co that blood can carry is equivalent to that of O₂. While O₂ is released at the tissue sites, allowing for new binding opportunities, Co remains strongly bound to hemoglobin. Consequently, during the capillary transit time, the fractional pressure of Co in the blood (Pco) does not reach equilibrium with the alveolar and atmospheric Pco, which typically occurs within approximately 0.75 seconds.

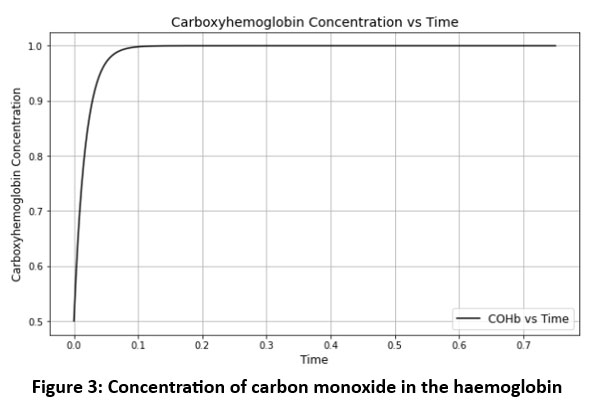

Blood transports Co similarly to O₂, both dissolved and chemically bound to hemoglobin. The reversible interaction between Co and hemoglobin forms concertation of carbon monoxide in the haemoglobin. Concentration of carbon monoxide in the haemoglobin as known as Carboxyhaemoglobin (COHb), also referred to as Co hemoglobin saturation (COHb).

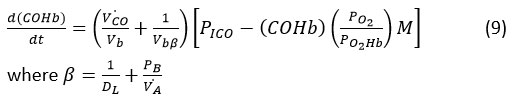

We have resolved the CFK equation to determine COHb levels in the blood.

where

Additionally, we employ the method developed by Roughton for estimating the oxygen dissociation curve ODC in the presence of carbon monoxide to determine the saturation of hemoglobin with Co in the presence of O₂. According to Haldane’s first law, the ratio of hemoglobin’s fractional pressure to its saturation with Co and O₂ is proportional.

From equation (9) and (11),

![]()

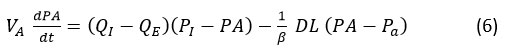

Differential equation derived of eq. (12), we get

For equation (13) derived graph for the concentration of carbon monoxide in the haemoglobin.

|

Figure 3: Concentration of carbon monoxide in the haemoglobin |

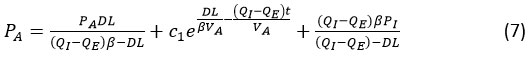

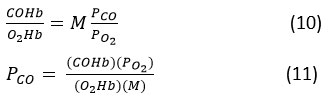

The volume of the gas in pulmonary capillary compartment,

![]()

Where σ is the blood fraction.

|

Figure 4: Carbon monoxide volume in the Pulmonary Capillary Compartment |

As a result, through systemic circulation, the blood’s concentration of CO and COHb remains constant. After one circulatory cycle, the arterial blood that leaves the pulmonary capillary returns as venous blood, but the CO concentration is the same as it remains in the arterial blood.

Table 1: Values of the model parameters for the carbon monoxide gas 22

| Parameter | Unit | Values |

| PA | mmHg | 0.3 |

| Pα | mmHg | 0.5 |

| P1 | mmHg | 1.0 |

| DL | mL.min-1 mmHg-1 | 30 |

| Q1 | L.min-1 | 0.000075 |

| QE | L.min-1 | 0.00075 |

| Qb | L.min-1 | 5.0 |

| Ca | mL.L-1 | 0.05 |

| Cv | mL.L-1 | 0.03 |

| β | L.mmHg-1 | 0.054188 |

Results

|

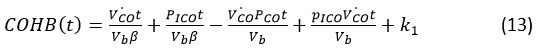

Figure 5: Carbon monoxide volume in various situations. |

Use the various value of the diffusing capacity in the equation (12) and derived the above the graph show that CO diffusing capacity depends on the fractional pressure. When the diffusion rate increases as the fractional pressure of CO increases. The graph illustrates the CO volume for various situations and different diffusing capacity values.

Discussion

In the study, the CO fractional pressure difference between alveoli and capillary compartment (PA – Pa) that depends on the diffusion capacity of the CO (DL), gas contact difference between arterial and venous blood are (Ca – Cv). The model can be derived for the carbon monoxide volume in alveoli and capillary compartment, it depends the carbon monoxide partial pressure in the compartment. For a given atmospheric CO concentration, the model can also be used to predict the variation of the blood’s COHb levels changes in exposure time. As the atmospheric concentration of increases, the blood’s COHb concentration also increases. The blood’s CO concentration depends on the fractional pressure and volume of CO. Also derived the graph for the carbon monoxide volume in the various situations it depends the various value of the diffusing capacity in the compartment. We were able to verify this by using Python to solve the differential equation. In the study, the model predicted only carbon monoxide gas is not for the remaining multi gases. Reducing of complexity of the model we can only consider exchanges of the gases at lungs only.

Conclusion

In the lungs, diffusion occurs to exchange carbon monoxide between the capillary blood and alveolar air. The differential equation for the volume of CO in the pulmonary capillary and alveolar compartments is derived by model. In the model, the diffusion process from the alveoli to the pulmonary capillary compartment is described, and the relationship between CO fractional pressure and volume in each compartment is defined. The concentration of the carbon monoxide in the haemoglobin in the capillary is described by the relationship between CO fractional pressure in the blood and blood volume. The numerical solution for the model was implemented using Python. A graphical representation was created to illustrate carbon monoxide diffusion in the pulmonary capillary and alveolar compartment model and to define the CO volume for various situations. Real air is composed of various gases. This model is valuable for understanding gas exchange between the alveoli and capillaries. Our future work will focus on improving the model to consider the exchange of several gases under such conditions.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank Veer Narmad South Gujarat University for granting the Ph.D. I am deeply grateful for the invaluable support offered by the Department of Mathematics, Veer Narmad South Gujarat University, Surat, throughout my research work. I extend my heartfelt gratitude to the facilities and resources provided were extremely helpful and have been instrumental in completing this work.

Funding Sources

The authors received no external funding support for this research work.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

This statement does not apply to this article.

Ethics Statement

This research did not involve human participants, animal subjects, or any material that requires ethical approval.

Consent Statement

This study did not involve human participants, and therefore, informed consent was not required.

Clinical Trial Registration

This research does not involve any clinical trials.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources –

Not Applicable

Authors’ Contribution

Conceptualization: Kaushal Patel and Nirali Patel developed the Model and designed the study.

Methodology: Kaushal Patel and Nirali Patel contributed to the development of the methodology.

Numerical and Programming: Nirali Patel performed Numerical analysis and Programming.

Writing: Nirali Patel wrote the initial draft of the manuscript.

Review & Editing: Kaushal Patel reviewed and edited the manuscript for intellectual content.

Supervision: Kaushal Patel supervised the work provided oversight.

Reference

- Sharan, Maithili, S. Selvakumar, and M. P. Singh. Mathematical model for the computation of alveolar partial pressure of carbon monoxide. International journal of bio-medical computing. 1990; 26(3): 135-147. https://doi.org/10.1016/0020-7101(90)90038-V

CrossRef - Macintyre, N., Crapo, R. O., Standardisation of the single-breath determination of carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. European Respiratory Journal. 2005;26(4):720-735. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.05.00034905

CrossRef - Leblanc P., Physiology of the respiratory system. Applied Respiratory Pathophysiology 2017: 15-32. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315177052

CrossRef - Fishman, A. P. Respiratory gases in the Regulation of the Pulmonary Circulation. Physiological Reviews. 1961; 41(1): 214-280. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.1961.41.1.214

CrossRef - Patel N. and Patel K., Mathematical Study of the Pulmonary Gas Exchange for the Respiratory System under Normal and Abnormal Conditions. Indian Journal of Science and Technology. December 2023; 16 (1): 1-7. 10.17485/IJST/v16iSP4.ICAMS10

CrossRef - Motterlini R., Clark, C. J., carbon monoxide releasing molecules: characterization of biochemical and vascular activities. Circulation research. 2002; 90(2) :17-24. https://doi.org/10.1161/hh0202.104530

CrossRef - Chien S., Peter P.C.Y., and Fung Y., pulmonary gas exchange. An introductory text to bioengineering. 2008: 181-207. 10.1109/MEMB.2009.934241

CrossRef - Holland RAB, Reaction rate of Carbon monoxide and hemoglobin. Ann NY Acad Sci 1970: 155-177. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1970.tb49782.x

CrossRef - Ryter, Stefan W., Kevin C. Ma, and Augustine MK Choi., Carbon monoxide in lung cell physiology and disease. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology. 2018; 314: 211-227. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpcell.00022.2017

CrossRef - Karbing D. S., Kjaergaard S., Andreassen S., and Rees S. E., Mathematical modeling of pulmonary gas exchange. Modeling methodology for physiology and medicine. 2014: 281-309. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-411557-6.00013-6

CrossRef - Patel, N., & Patel, K. A study of the exchange of carbon dioxide in the human respiration system using lumped constant model. Proceedings of 4th Prof. PC Vaidya. Department of mathematics, Veer Narmad South Gujarat University. 2024:1-17

- Ike I. S., and Aneke L. E. and Mbah G. C. E., Mathematical Modeling and Simulation of a Diffusion Process in the Human Bloodstream. Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences. 2022: 260-268.

- Patel N. and Patel K., Estimation of Pulmonary Gas Exchange in The Human Respiratory System Under Normal and Abnormal Conditions. Bioscience Biotechnology Research Asia, January. 2023. http://dx.doi.org/10.13005/bbra/3086

CrossRef - Raffe, Marc R., Respiratory gas transport, The Veterinary ICU Book. CRC Press, 2020: 15-23. https://doi.org/10.1201/9780138719128

CrossRef - Pendergast, David R., Albert Olszowka, and Leon E. Farhi., Cardiovascular and pulmonary responses to increased acceleration forces during rest and exercise. Aviation, space, and environmental medicine. 2012; 83(5): 488-495. 10.3357/ASEM.3127.2012

CrossRef - Wagner, Peter D., and John B. West. Ventilation-Perfusion. Ventilation, Blood Flow, and Diffusion. 2012: 219.

CrossRef - Tsega E. G. and Katiya V. K., A Mathematical Modeling of Pulmonary Gas Exchange in Human. International Journal of Current Advanced Research. 2018: 11974-11977.

- Motterlini, Roberto, and Roberta Foresti., Biological signaling by carbon monoxide and carbon monoxide-releasing molecules. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology. 2017; 312: 302-313. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpcell.00360.2016

CrossRef - Collier CR, Oxygen affinity of human blood in presence of Carbon monoxide. J Appl Physiol. 1976: 487-490. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.1976.40.3.487

CrossRef - Heinemann, Stefan H., Toshinori, Matthias, Alexander Schiller., Carbon monoxide physiology, detection and controlled release. Chemical Communications. 2014; 50(8) :3644-3660. https://doi.org/10.1039/C3CC49196J

CrossRef - Hughes, J. M. B., Pride, N. B., Examination of the carbon monoxide diffusing capacity (DLCO) in relation to its KCO and VA compartments. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2012; 186(2) :132-139. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201112-2160CI

CrossRef

- Filley, G. F. Maclntosh, D. J., Carbon monoxide uptake and pulmonary diffusing capacity in normal subjects at rest and during exercise. The journal of clinical investigation. 1954; 33(4) :530-539. 10.1172/JCI102923

CrossRef - Okada Y, Tyuma I, Ueda Y and Sugimoto T: Effect of carbon monoxide on equilibrium between oxygen and hemoglobin, (1976): 471-475. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplegacy.1976.230.2.471

CrossRef - Maithili, S. selvankumar, M.P. singh., Mathematical model for the Computation of Alveolar Fractional Pressure of Carbon monoxide. International journal biomed compute 1990; 26(3): 135-47. https://doi.org/10.1016/0020-7101(90)90038-V

CrossRef - Roughton FJW, The equilibrium of carbon monoxide with human hemoglobin in whole blood. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1970: 177-188. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1970.tb49784.x

CrossRef

Abbreviations

PI : entire fractional pressure in the alveoli

PA : alveoli fractional pressure

Pa : pulmonary capillary Fractional Pressure

Pv : venous blood fractional pressure

DL : diffusing capacity

Ca : gas content in arterial blood

Cv : gas content in venous blood

Ct : gas content in tissues

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.