Manuscript accepted on : 21-03-2025

Published online on: 22-05-2025

Plagiarism Check: Yes

Reviewed by: Dr. Karuna Priyachitra

Second Review by: Dr. Ramdas Bhat

Final Approval by: Dr. Ahmad Ali

GCMS Analysis of Anti-Diabetic and Antioxidant Metabolites from PENICILLIUM Javanicum NZ JNTU

Shaik Nasireen Begum1* , Pachalapalli Dinesh Sankar Reddy2

, Pachalapalli Dinesh Sankar Reddy2 and Gandavaram Syam Prasad3

and Gandavaram Syam Prasad3

1Department of Biotechnology, Jawaharlal Technological University Anantapur, AP, India.

2Department of Chemical Engineering, National Institute of Technology NIT-AP Tadepalligudem, AP, India.

3Department of Chemistry, Sree Vidyanikethan Engineering College, Tirupathi, AP, India.

Corresponding Author E mail- sn.nasireen4@gmail.com

DOI : http://dx.doi.org/10.13005/bbra/3398

ABSTRACT: The most promising sources of possible secondary metabolites with biological and pharmacological characteristics are fungi. Biological uses of soil fungus are less studied than those of marine and endophytic fungi. The soil fungus Penicillium javanicum was isolated and examined for antioxidant and anti-diabetic properties in the current study. Optimal growing conditions were used to develop the fungus on a wide scale, and serial solvent extraction was used to extract the crude metabolites. Amid P. javanicum extracts ethyl acetate extract presented the highest anti-diabetic activity conforming to 73.24% α-amylase inhibition activity at 400µg/ml to IC50 value of 261.52µg/ml compared to 15.47µg/ml of standard Acarbose. Chloroform extract of P. javanicum inhibited 53.33% amylase activity in contrast to 24.94% and 8.69% anti-diabetic activity of 400µg/ml of ethanol and petroleum ether extracts. Further, ethyl acetate extract evaluated for free radical scavenging potential indicated 70.14% antioxidant activity at 300µg/ml with IC50 value of IC50 value of 166.17µg/ml. The secondary metabolites of P. javanicum in all the extracts analyzed by Gas Chromatography Mass Spectroscopy (GCMS) revealed three dominant peaks corresponded to 1-Hexadecanol, 9,12-Octadecadienoyl chloride, (Z,Z)-, and 2-Methyl-1-undecanol in the ethyl acetate extract. Whereas, chloroform and ethanol extracts contained 17-Octadecynoic acid and Z,Z-3,13-Octadecedien-1-ol along Nonadecane respectively as dominant metabolites. These metabolites have been reported for antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-malignancy activities, and biocontrol agents against plant pathogens. However, the anti-diabetic and antioxidant activity of metabolites of P. javanicum are scarce and being reported for the first time in the present study. The biological activities of secondary metabolites of P. javanicum reported currently are other than soil fungi such as plants and other sources. Hence there is a huge scope to study these metabolites exclusively to discover a novel anti-diabetic drug.

KEYWORDS: Anti-diabetic; Antioxidant; GCMS analysis; Penicillium javanicum; Pharmacological properties; Secondary metabolites,Soil fungi

Download this article as:| Copy the following to cite this article: Begum S. N, Reddy P. D. S. Prasad G. S. GCMS Analysis of Anti-Diabetic and Antioxidant Metabolites from PENICILLIUM Javanicum NZ JNTU. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(2). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Begum S. N, Reddy P. D. S. Prasad G. S. GCMS Analysis of Anti-Diabetic and Antioxidant Metabolites from PENICILLIUM Javanicum NZ JNTU. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(2). Available from: https://bit.ly/4mr0IVp |

Introduction

Genomic research in fungal species indicated a huge potential for secondary metabolite biosynthesis in which about 80% of fungal secondary metabolites are yet to be discovered and only 20% is known1. This is because the majority of secondary metabolites are synthesized against genetic signals in coordination with numerous genes organized in the biosynthetic gene cluster (BGCs) in which only a small fraction is encoded for currently available pharmaceutical and antibiotic compounds. Hence presently, the study of these gene clusters is a major challenge in research as they are known to be cryptic or silent when cultured under laboratory condition and these unexplored inactive genes are the large reservoir of secondary metabolites2. Several ways of gene organization in BGCs are a basis for encoding a core or tailoring enzyme responsible for the biosynthesis of various backbones of secondary metabolites3,4. Therefore, intense research in fungal genomics and secondary metabolites plays a substantial role in the drug discovery process.

A review of scientific articles published in 2023 revealed the majority of fungal metabolites i.e., 1/3rd (39%) are of plant origin, only a few amounts of metabolites are derived from marine (31%), soil (12%), animals (6%), and others (12%)1. Henceforward, there is a huge scope to explore these soil fungi in the production of various secondary metabolites for various scientific applications. Among the fungi, the genus Penicillium is one of a versatile group representing more than 300 species with different habitats, and lifestyles, and ubiquitous. The study of large-scale genome among 24 Penicillium species revealed the majority of the core genome is encoded for chemically and structurally diverse secondary metabolites. For instance, the cytochrome P450 genes variation is associated with a wide diversity of secondary metabolites, and about 1317 putative BGCs, non-ribosomal peptide synthetase, and polyketide synthase have been mapped and identified5.

The genus of Penicillium has been proven for its diverse production of bioactive metabolites with potential medical applications such as antimicrobials active against various bacteria, fungi, and viruses, antioxidant, anticancer, anti-diabetic, anti-inflammatory and other activities6,7. As far as the anti-diabetic potential of genus Penicillium is concerned many α-glucosidase inhibitor molecules have been reported since 2010. Some of α-glucosidase inhibiting compounds include BenzomalvinA, Benzomalvin B, Quinolactacins A1, Quinolactacins B1, Asperphenamate isolated from Penicilliumspathulatum, Chrysines B, C, Methyl-30-methoxy-3,5-dichloroasterric acid, Methyl chloroasterrate, Mono-chlorosulochrin synthesized from Penicilliumchrysogenum and Bacillisporin A, Bacillisporin B isolated from Penicilliumaculeatum8,-10.

P.javanicum isolated from various sources has been reported to produce various important bioactive metabolites. Among seven indole-diterpenes and two polyketides isolated from marine-derived P. javanicum, no significant activity was noticed by all indole diterpenes, and moderate to significant antibacterial activity was observed when polyketides were tested11 . P. javanicumMSC-R1 an endophyte from Millettiaspeciosa Champ synthesis an acid polysaccharide which showed no toxicity towards RAW 264.7 cells and indicated strong anti-inflammatory activity12. Two novel unsaturated fatty acids and a sesquiterpenoid isolated from soil fungus P. javanicumHK1-22 were evaluated for antifungal activity in which a sesquiterpenoid indicated strong antifungal activity against four plant pathogens13. However, metabolites of P.javanicum active against diabetes are not been reported in either crude or pure form. Therefore, the present study is undertaken to investigate the anti-diabetic and antioxidant activities of crude metabolites of P.javanicum.

Materials and Methods

Media, Enzyme, and Chemicals Potato dextrose broth, Petroleum ether, Chloroform, Ethyl acetate, Ethanol, 0.02 M Sodium Phosphate Buffer, Sodium chloride (NaCl), Starch, Dinitrosalicylic acid (DNSA) reagent,Acarbose,α−Amylase, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), Methanol, Ascorbic acidConc. Sulfuric acid (H2SO4), Sodium hydroxide (NaOH), 70% Ethanol, Disodium hydrogen phosphate (Na2HPO4.2H2O), Sodium dihydrogen phosphate (NaH2PO4.H2O), Sodium Chloride (NaCl), Potassium sodium tartrate tetrahydrate, Sodium hydroxide (NaOH),and Dextrosewere purchased from Hi Media company from Bangalore.

Mass production, extraction, and anti-diabetic activity of P. javanicumNZ JNTU extracts

The secondary metabolites of P. javanicumare rarely explored for scientific applications. Hence in the current investigation, P. javanicam is cultivated in optimum growth conditions using optimum inoculum concentration of spore suspension. The fungus was grown until maximum anti-diabetic secondary metabolites were produced in potato dextrose broth and the fungal mat was separated from the medium and extracted using petroleum ether, chloroform, ethyl acetate, and ethanol solvents successfully. The ethyl extract which showed the highest anti-diabetic activity was further evaluated for various biological applications.

Anti-diabetic activity

All the extracts of P. javanicumwere evaluated for anti-diabetic potential using a slightly modified α-amylase inhibition assay14. To 100µl of different concentrations of all extracts of P. javanicumi.e., 12.5, 25, 50, 100, 200, and 400µg/ml, 200µl of α-amylase prepared at 0.5mg/ml in 0.02 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.9) with 0.006M NaCl was added. All the tubes were incubated for 20 minutes at 37ºC and 250µl of 1%starch prepared in 0.02 M sodium phosphate buffer with 0.006M NaCl (pH 6.9) was added. The tubes were incubated for 15 minutes at 37ºC and 2ml of DNS reagent was added to all the tubes and incubated at 100°C in a water bath for 10 minutes. The absorbance was recorded at 540nm using a blank solution (buffer and amylase) in a spectrophotometer. The absorbance of positive control containing acarbose in place of the extract was also measured. The percentage of inhibition of α-amylase activity was calculated using the below-mentioned formula.

Where, A control -absorbance of the control and A sample – absorbance of the sample

Antioxidant activity

Free radical scavenging capacity of ethyl acetate extract of P. javanicum was established by DPPH radical scavenging assay15. Ethyl acetate extract of P. javanicum was prepared at different concentrations i.e., 50, 100, 150, 200, 250, and 300µg/ml in methanol. DPPH solution was prepared by dissolving 24mg DPPH in 100 ml. Both solutions were mixed at a 1:1 ratio and incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature. Ascorbic acid was used as a positive control. Post incubation, absorbance was recorded at 517nm using a spectrophotometer using methanol as blank.

GCMS Analysis of P. javanicumextracts

The secondary metabolites present in all extracts of P. javanicum except petroleum ether extract showing moderate to significant anti-diabetic were further investigated by analyzing extracts by GCMS and matching the chromatogram peak with the NIST library. All the extracts except petroleum ether extract were dissolved HPLC grade methanol and resultant solutions were filtered using 0.22µm pore size filters. The total run time of the samples was set for 30 minutes and 1µl of each extracted sample was injected through auto-injection mode at a temperature of 250°C using 10:1 split mode. All the extract samples of the fungus were run with a flow rate of 1ml/minute. The oven temperature of the gas chromatography (GC) was initially maintained at 60°C for 2 minutes and further increased at 10ºC/minute until its attained temperature of 300ºC for 6 minutes of holding time. Elite-5MS column with an internal diameter of 250μm df was used and the carrier gas used was Helium. The molecular mass of metabolites present in each extract was detected in the mass spectrum using mass condition of 230°C source temperature and transfer temperature of 230°C with 2 minutes solvent delay. Metabolites of the extracts were scanned from 50 – 600 Daltons in the Mass spectrum and the electron impact method was used as the detection system. After running each extract for a total run time the chromatogram was obtained. The peaks present in the chromatogram of each fungal extract were interpreted by matching with possible compounds present in the NIST library and the first ten possible compounds that matched with peaks were identified along with their mass.

Results

Novel biological applications particularly the anti-diabetic activity of a rare speciesP. javanicum isolated from soil are investigated in the current investigation. The fungus isolated from soil was cultured in mass scale in an optimized medium and metabolites were extracted using different solvents. All the fungal extracts were tested for anti-diabetic activity and the ethyl acetate extract of the fungus revealing substantial anti-diabetic activity was further evaluated for various other biological applications

α-Amylase inhibition activity of P. javanicum extracts

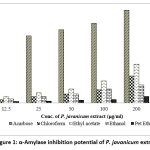

All the extracts of P. javanicum investigated for anti-diabetic activity showed increased α-amylase inhibition activity with increased concentration of all fungal extracts tested (dose-dependent manner) and the results of anti-diabetic activity are indicated in Figure 1. Amid fungal extracts, the highest anti-diabetic activity was observed in the ethyl acetate extract of the fungus which inhibited 73.24% of α-amylase activity at 400µg/ml of extract. Following this, the same concentration of chloroform extract of fungus showed 53.33% α-amylase inhibition activity being the second most anti-diabetic crude metabolites.

|

Figure 1: α-Amylase inhibition potential of P. javanicum extracts |

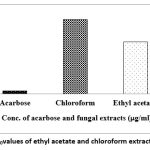

The IC50 values of crude metabolites of ethyl acetate and chloroform extracts of the fungus were 261.52µg/ml and 374.67µg/ml respectively compared to the IC50 value of 15.47µg/ml of acarbose standard (Figure 2). However, the ethanol extracts of the fungus showed moderate anti-diabetic potential indicating 24.88% α-amylase inhibition activity compared to the least activity of petroleum ether i.e., 2.24%. Hence in current research, ethyl acetate extract of P. javanicum showed significant anti-diabetic activity i.e., 73.24% against 99.14% ant-diabetic activity of a positive control acarbose tested at same concentration.

|

Figure 2: The IC50values of ethyl acetate and chloroform extract of P. javanicum |

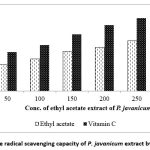

Antioxidant activity of ethyl acetate extract of P. javanicum

Ethyl acetate extract of P. javanicum assessed for antioxidant activity showed significant free radical scavenging capacity with an increased amount of fungal extract when tested by DPPH assay as shown in Figure 3. The antioxidant activity was increased with an increased concentration of ethyl acetate in which the highest activity was observed at 300µg/ml of ethyl acetate corresponding to 70.14% of antioxidant activity. The IC50 value of ethyl acetate extract was found to be 166.17µg/ml compared to the IC50 value of 62.53 µg/ml of the standard vitamin C. The IC50 values of ethyl acetate and vitamin C are mentioned in Table 1. Therefore, the crude metabolites of ethyl acetate extract of P. javanicum revealed considerable free radical scavenging potential in tested concentration.

Table 1: Antioxidant potential and IC50 value of P. javanicum extract

| Conc. of Extract/Ascorbic C (µg/ml) | Antioxidant activity (%) | |

| Ethyl acetate | Vitamin C | |

| 50 | 32.83± 0.030 | 47.13± 0.032 |

| 100 | 39.92± 0.030 | 57.09±0.025 |

| 150 | 49.25± 0.010 | 70.52±0.015 |

| 200 | 54.10± 0.015 | 81.81±0.032 |

| 250 | 62.31± 0. 010 | 92.43±0.015 |

| 300 | 70.14± 0.020 | 96.59±0.020 |

| Control | 00.00 ± 0.020 | 00.00± 0.020 |

| IC50 value (µg/ml) | 166.17 | 62.53 |

|

Figure 3: Free radical scavenging capacity of P. javanicum extract by DPPH assay |

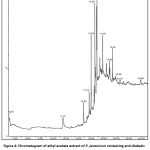

GCMS-based secondary metabolites detection in P. javanicum extracts

The extracts showing anti-diabetic activity were analyzed by GCMS and results indicated various bioactive compounds in all the extracts. The list of possible secondary metabolites present in the extracts of P. javanicum which were detected using the NIST library available with GCMS. The chromatogram of ethyl acetate extract of P. javanicum indicating several peaks with different retention time (RT) values is shown in Figure 4. On the whole, 11 peaks were noticed in the chromatogram of ethyl acetate extract corresponding to various compounds eluted at 11.57, 14.82, 15.73, 16.03, 16.62, 16.96, 17.86, 18.92, 19.42, 19.88, 20.61, and 23.89 minutes. Matching peaks of RT values 11.58 and 14.82 with NIST library attributed to the compounds Undecane and Decyloctyl ether with a molecular mass of 156 and 270 respectively. The peaks with RT values 15.73 and 16.03 were found due to the presence of Hydroxylamine, O-decyl- and 2-Methyl-1-undecanolin ethyl acetate extract of the fungus. The fungal secondary metabolites detected in all extracts of P. javanicum with their elution time (RT), mass, and molecular formula are shown in Table 2. Although, bothchromatograms of chloroform and ethanol extracts of the fungus showed similar peaks as found in the ethyl acetate with the same RT values they corresponded to different metabolites in the NIST library except peak values 16.03, 18.92, and 19.42 which are due to the presence of Pentadecanoic acid, 2,6,10,14-tetramethyl-, methyl ester, Didodecyl phthalate, and Nonadecane respectively Figure 4.. However, ethyl acetate extract of Penicillium species also revealed similar peaks as noticed in chloroform extract along with two additional peaks detected at 14.8 and 15.7 minutes.

Table 2: Secondary metabolites of P. javanicumextracted using different solvents

| Peak | RT | Molecular formula, Mass | Secondary metabolites present in the extracts of P. javanicum | ||

| Chloroform | Ethyl acetate | Ethanol | |||

| 1 | 11.50 | C15H32, 212 | Dodecane, 2,6,11-trimethyl- | – | – |

| 2 | 11.57 | C11H24, 156 | – | Undecane | – |

| 3 | 14.82 | C18H38O, 270 | – | Decyloctyl ether | |

| 4 | 15.73 | C10H23NO, 173 | – | Hydroxylamine, O-decyl- | – |

| 5 | 16.03 | C20H40O2, 312 | – | 2-Methyl-1-undecanol | – |

| 6 | 16.08 | C20H40O2, 312 | Pentadecanoic acid, 2,6,10,14-tetramethyl-, methyl ester | – | Pentadecanoic acid, 2,6,10,14-tetramethyl-, methyl ester |

| 7 | 16.62 | C18H31ClO, 298 | 9,12-Octadecadienoyl chloride, (Z,Z)- | ||

| 8 | 16.63 | C12H24O, 184 | Oxirane, decyl- | – | – |

| 9 | 16.65 | C20H42O2S, 346 | – | – | Di-n-decylsulfone |

| 10 | 16.90 | C18H32O2, 280 | 17-Octadecynoic acid | – | – |

| 11 | 16.91 | C18H34O, 266 | – | – | Z,Z-3,13-Octadecedien-1-ol |

| 12 | 16.96 | C16H34O, 242 | – | 1-Hexadecanol | – |

| 13 | 17.86 | C20H42O2S, 346 | – | Di-n-decylsulfone | |

| 14 | 17.87 | C12H22Si2, 222 and C6H18O3Si3, 222 | 1,4-Bis(trimethylsilyl)benzene | – | Cyclotrisiloxane, hexamethyl- |

| 15 | 18.91 | C32H54O4, 502 | Didodecyl phthalate | – | – |

| 16 | 18.92 | C32H54O4, 502 and C18H45AsO3Si3, 468 | Didodecyl phthalate | Tris(tert-butyldimethylsilyloxy)arsane | |

| 17 | 19.42 | C19H40, 268 | Nonadecane | Nonadecane | Nonadecane |

| 18 | 20.61 | C20H42O2S, 346 | – | Di-n-decylsulfone | – |

| 19 | 23.87 | C18H45AsO3Si3, 468 | – | – | Tris(tert-butyldimethylsilyloxy)arsane |

| 20 | 23.88 | C9H27AsO3Si3, 342 | Arsenous acid, tris(trimethylsilyl) ester | – | – |

| 21 | 23.89 | C18H45AsO3Si3, 468 | – | Tris(tert-butyldimethylsilyloxy)arsane | – |

|

Figure 4: Chromatogram of ethyl acetate extract of P. javanicum containing anti-diabetic metabolites. |

In total, 18 compounds have been detected in all the extracts of P. javanicum in which the majority of compounds i.e., 10 metabolites have been detected in ethyl acetate extract. The peaks with RT values 16.90, 16.91, and 16.96 in chloroform, ethanol, and ethyl acetate extracts matched with the fungal metabolite 17-Octadecynoic acid, Z,Z-3,13-Octadecedien-1-ol, and 1-Hexadecanol respectively were dominantly found in the fungal extracts. In chloroform and ethanol extract of P. javanicum total of eight and seven metabolites were detected out of which two metabolites as Pentadecanoic acid, 2,6,10,14-tetramethyl-, methyl ester, and Nonadecane are detected in all the extracts. The structures of all the metabolites of P. javanicumdetected in all the extracts are shown in Figure 5.

|

Figure 5: Structures of secondary metabolites of P. javanicum detected using GCMS library |

Discussion

The prevalence of diabetes across the world is worsening every year in terms of morbidity and mortality as evidenced by World Health Organization (WHO) Report 2024. Incidences of diabetes escalated from 200 million to 830 million from 1993 to 2022, particularly in low and middle-income nations. The percentage of adults aged 18 or older suffering from diabetes doubled from 1990 to 2022 ranging from 7% -to 14% respectively. In addition, more than 50% of total diabetic cases aged 30 or more are still not under medications due to being unaware of the diseases. Alongside, the death rate associated with diabetes or its complications mainly cardiovascular, kidney, chronic respiratory diseases, and malignancies also intensified globally by 20% from 2000 to 201917. In 2021, 1.6 million deaths were directly contributed by diabetes (47% are of those aged 30-70 years) about 11% of deaths were due to cardiovascular problems and 5,30,000 were attributed to high blood glucose and kidney diseases17.18.

Through the already residing global burden of the diabetic, a global rise in the prevalence of adolescent and young diabetes among the age 10-24years from 56.02 per 1,00,000 to 123.86 per 1,00,000 from 1990 to 2021 is further posed a challenge to public health19. Consequently, there is a need for an emergency measure to tackle the rising incidence of diabetes in all age groups across the globe. Besides the perilous upswing in diabetes cases, increased literacy, wakefulness about diabetes, and awareness programs driven by modern literature, and media have led to increased demand for the novel drug for complete uprooting of diabetes. Hence, in the current research, soil fungi were tried to explore for anti-diabetic applications.

Diabetes is a chronic metabolic disorder associated with defective or scarce insulin production attributing subsequently to anomalous carbohydrate metabolism such as a rise in blood glucose and other diabetic-associated problems20. Several anti-diabetic resources have been reported in the nature in which plants, marine microflora, and recently endophytic fungi have been extensively studied21-23. However anti-diabetic molecules from soil fungi are not much explored. Therefore, in the present investigation, a soil fungus P. javanicum was screened for anti-diabetic and antioxidant activity. Mass production of metabolites was carried out using optimized growth conditions. Metabolites of the fungus were extracted from the fungal mat by successive extraction using different solvents. The crude metabolites of ethyl acetate extract revealed a significant anti-diabetic activity compared to other fungal extracts.

Further, ethyl acetate evaluated for antioxidant capacity showed promising free radical scavenging activity. The crude metabolites present in chloroform, ethyl acetate, and ethanol extracts of P. javanicam were analyzed by GCMS, and peaks thus obtained were matched in the NIST library. The library revealed several secondary metabolites of fungi in which dominantly found metabolites were 17-Octadecyn;oic acid, Z,Z-3,13-Octadecedien-1-ol, and 1-Hexadecanol, followed by 9,12-Octadecadienoyl chloride, (Z,Z)-, Oxirane, decyl-, Di-n-decylsulfone, 2-Methyl-1-undecanol, and Pentadecanoic acid, 2,6,10,14-tetramethyl-, methyl ester. Many of these have been reported for various biological activities. Although methanol extract from the needles of AbiesmarocanaTrab containing 17-Octadecynoic acid revealed antioxidant activity, the metabolites are widely reported for several medical applications such as development of periapical abscesses, improvement of contractile response, and as a suicide-substrate inhibitor24-27, etc,. The metabolites Z,Z-3,13-Octadecedien-1-ol was identified in the isopropanol extract of Actinidiaarguta fruit revealed substantial antioxidant and antibacterial activity compared to other reported values31. The hydrodistilled oil extracted from the plant Myricaesculenta(stem bark) containing n-hexadecanol as the major volatile oil indicated potential antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-inflammatory activity32.

Dodecane, 2,6,11-trimethyl- detected in the chloroform extract was previously identified in various extracts of Gymnemasylvestre plant which have been reported for free radical scavenging activity33. The hydrocarbon secondary metabolite, undecane was also synthesized by several Penicillium species including by P. jenseii28. 2-Methyl-1-undecanol was isolated from the crude extract of the fungus Trichodermaharzianum which is widely reported as a biocontrol agent against various plant pathogens and as a plant growth-promoting fungus36. The GCMS analysis of Oyster mushrooms, Pleurotusostreatus indicated 32 bioactive compounds including 9,12-Octadecadienoyl chloride, (Z,Z)- and other compounds revealed antioxidant, anticancer, and antibacterial activities38. The crude extract of dried leaves of Feronia limonia containing Oxirane, decyl-, n-hexadecanoic acid, and other constituents is antimicrobial and anti-larvicidal37.

Ethyl acetate extract of three endophytic fungi such as Cladosporiumcladosporioides, Bipolarisaustraliensis, and Graminicolous helminthosporium containing Tris(tert-butyldimethylsilyloxy) arsane, Arsenous acid, 1,4-Bis(trimethylsilyl)benzene, 2-Ethylacridine, Cyclotrisiloxane, and other components revealed potential antibacterial, antifungal, and antioxidant activities39. Phthalate compounds namely Didodecyl phthalate and Di-n-decylsulfone present in the crude extract of Pleione maculate and Cardiospermumhalicacabum l. revealed several biological activities such as larvicidal, antagonistic, antihelminthic, antitumor, and antimicrobial properties40,41. Another phthalate substance such as didodecyl phthalate present in the extract of Mukiamaderaspatana (linn.) M. Roem of family Cucurbitaceae and Trigonellafoenumgrecum showed wide therapeutic potential of antifouling, antimicrobial, diuretic, stimulation of excretion of uric acid, antihypertensive, and vasodilator properties42,43.

Nonadecane reported earlier in the crude fungal extracts of P. purpurogenum, P. limosum Strain AK-7, and Pestalotiopsisneglecta BAB-5510 possess antioxidant, antibacterial, cytotoxicity against cancer cells28-30. The crude extract of leaves of the plant Sonchusmaritimuscontaining decyloctyl ether revealed considerable anti-inflammatory activity34 . The Hydroxylamine, O-decyl- and nonadecane-containing crude extract of endophytic fungi such as Aspergilluscejpiiwas found to be active against both Gram-positive and negative bacterial pathogens including antibiotic resistance bacterial pathogens35.Therefore, the detailed GCMS analysis confers the immense potential of secondary metabolites of P. javanicum as far as their biological activity and their application in medicine as potential therapeutic agents are concerned. Although the metabolites of P. javanicum showed wide biological activities as discussed above, studies related to antidiabetic and antioxidant activity are very scarce, particularly from P. javanicum, and probably this is the first report. Moreover, the reported studies are yet in the preliminary stage as they are studied in crude metabolite form which promises enormous and diverse biological activities. Majority of these secondary metabolites have majorly reported other than soil fungi such as plants and other sources. Hence there is a huge scope to study these metabolites individually for the benefit of medical science.

Conclusion

The soil fungus, P. javanicum screened for anti-diabetic activity and was cultivated on a mass scale, and secondary metabolites were extracted from the fungal mat. Ethyl acetate extract of P. javanicum revealed significant α-amylase inhibition and antioxidant activity. Analysis of metabolites present in the crude extracts of the fungus by GCMS indicated several bioactive molecules possessing antibacterial, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties. However, these metabolites are yet to be explored for their anti-diabetic potential. Moreover, most of these secondary metabolites have scarcely been reported from Penicillium species, particularly for anti-diabetic activity. Hence, in the current study anti-diabetic activity ofcrude metabolites of P. javanicum is reported for the first time. Furthermore, a promising biological application of these metabolites at the preliminary stage using crude extract indicated huge hope for a better anti-diabetic drug development process.

Acknowledgement

The Authors would like to thank JNTUA University for providing necessary to carry the Ph.D work. M S Kori Laboratory is highly appreciated from allowing the growth and characterization studies.

Funding Sources

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement-

This statement does not apply to this article.

Ethics Statement

This research did not involve human participants, animal subjects, or any material that requires ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not involve human participants, and therefore, informed consent was not required.

Clinical Trial Registration

This research does not involve any clinical trials.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

Not Applicable

Author Contributions

Shaik Nasireen Begum: Writing – Original Draft.

Puchalapalli DInesh Sankar Reddy: Review & Editing.

Gandavaram Syam Prasad: final approval of the manuscript

References

- Shi, Ying, Minhui Ji, Jiayu Dong, Dongxiao Shi, Yitong Wang, Longhui Liu, Shuangshuang Feng, and Ling Liu. 2024. “New Bioactive Secondary Metabolites from Fungi: 2023.” Mycology 15 (3): 283–321. doi:10.1080/21501203.2024.2354302.

CrossRef - Zakariyah, R.F., Ajijolakewu, K.A., Ayodele, A.J. et al. Progress in endophytic fungi secondary metabolites: biosynthetic gene cluster reactivation and advances in metabolomics. Bull Natl Res Cent 48, 44 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-024-01199-x

CrossRef

- Zhgun AA (2023) Fungal BGCs for production of secondary metabolites: main types. Central Roles in Strain Improvement, and Regulation According to the Piano Principle 24(13):11184–11184. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241311184

CrossRef

- Keller NP (2018) Fungal secondary metabolism: regulation, function and drug discovery. Nat Rev Microbiol 17(3):167–180. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-018-0121-1

CrossRef

- Jintu Rabha, Dhruva K. Jha Chapter 12 – Metabolic Diversity of Penicillium. New and Future Developments in Microbial Biotechnology and BioengineeringPenicillum System Properties and Applications2018, Pages 217-234.

CrossRef

- Xiaoqin Zhang, Qizhao Yin, Xuanyi Li, Xiaowan Liu, Houxing Lei, Bin WuStructures and bioactivities of secondary metabolites from Penicillium genus since 2010. Fitoterapia, Volume 163, November 2022, 105349

CrossRef

- Lu-TingDai, Li Yang, Jiao-Cen Guo, Qing-Yun Ma, Qing-Yi Xie, Li Jiang, Zhi-Fang Yu, Hao-Fu Dai, You-Xing Anti-diabetic and anti-inflammatory indole diterpenes from the marine-derived fungus Penicillium sp. ZYX-Z-143. Bioorganic Chemistry, Volume 145, April 2024, 107205.

CrossRef - Wang JF, Zhou LM, Chen ST et al (2018) New chlorinated diphenyl ethers and xanthones from a deep-sea-derived fungus Penicilliumchrysogenum SCSIO 41001. Fitoterapia, 125:49–54.

CrossRef - Valle PD, Martı´nez AL, FigueroaMet al (2016) Alkaloids fromthe fungus Penicilliumspathulatum as a-glucosidase inhibitors. Planta Med 82:1286–1294.

CrossRef - Huang H, Feng X, Xiao Z et al (2011) Azaphilones and p-terphenyls from the mangrove endophytic fungus Penicilliumchermesinum (ZH4-E2) isolated from the South China Sea. J Nat Prod 74:997–1002.

CrossRef - Liang, ZY., Shen, NX., Zhou, XJ. et al.Bioactive Indole Diterpenoids and Polyketides from the Marine-Derived Fungus Penicilliumjavanicum. Chem Nat Compd 56, 379–382 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10600-020-03039-6.

CrossRef - Lin-Hao Lai, Min-Hua Zong, Zhi Huang, Zi-Fu Ni, Pei Xu, Wen-Yong Lou. Purification, structural elucidation and biological activities of exopolysaccharide produced by the endophytic Penicilliumjavanicumfrom Millettiaspeciosa Champ. Journal of Biotechnology, Volume 362, 20 January 2023, 54-62.

CrossRef - Zhao-Yang Liang, Nan-Xing Shen, Yao-Yao Zheng, Jin-Tao Wu, Li Miao, Xiu-Mei Fu, Min Chen, Chang-Yun Wang. Two new unsaturated fatty acids from the mangrove rhizosphere soil-derived fungus Penicilliumjavanicum HK1-22. Bioorganic ChemistryVolume 93, December 2019, 103331

CrossRef - Elyasiyan U, Nudel A, Skalka N, Rozenberg K, Drori E, Oppenheimer R, Kerem Z, Rosenzweig T. Anti-diabetic activity of aerial parts of Sarcopoteriumspinosum. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017 Jul 6;17(1):356. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-1860-7. PMID: 28683738; PMCID: PMC5501114.

CrossRef - Huneif M.A., Alshehri D.B., Alshaibari K.S., Dammaj M.Z., Mahnashi M.H., Majid S.U., Javed M.A., Ahmad S., Rashid U., Sadiq A. Design, synthesis and bioevaluation of new vanillin hybrid as multitarget inhibitor of α-glucosidase, α-amylase, PTP-1B and DPP4 for the treatment of type-II diabetes. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022;150:113038. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113038.[DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

CrossRef - Suriyaprom S, Srisai P, Intachaisri V, Kaewkod T, Pekkoh J, Desvaux M, Tragoolpua Y. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activity on LPS-Stimulated RAW 264.7 Macrophage Cells of White Mulberry (Morus alba L.) Leaf Extracts. Molecules. 2023 May 28;28(11):4395. doi: 10.3390/molecules28114395. PMID: 37298871; PMCID: PMC10254316.

CrossRef - Diabetes-World health organization report 2024. Retrieved from tttps://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes#: ~:text=In%202022,%2014%%20of %20adults%20aged% 2018%20years %20and accessed on 05-01-2025.

- Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Results. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. 2024 (https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/).

- Xu, ST., Sun, M. & Xiang, Y. Global, regional, and national trends in type 2 diabetes mellitus burden among adolescents and young adults aged 10–24 years from 1990 to 2021: a trend analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. World J Pediatr(2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-024-00861-8.

CrossRef - Ye G, Huang C, Li J, Chen T, Tang J, Liu W, Long Y. Isolation, Structural Characterization and Antidiabetic Activity of New Diketopiperazine Alkaloids from Mangrove Endophytic Fungus Aspergillus 16-5c. Mar Drugs. 2021 Jul 20;19(7):402. doi: 10.3390/md19070402. PMID: 34356827; PMCID: PMC8304462.

CrossRef - Alam S, Sarker MMR, Sultana TN, Chowdhury MNR, Rashid MA, Chaity NI, Zhao C, Xiao J, Hafez EE, Khan SA, Mohamed IN. Antidiabetic Phytochemicals From Medicinal Plants: Prospective Candidates for New Drug Discovery and Development. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022 Feb 24;13:800714. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.800714. PMID: 35282429; PMCID: PMC8907382.

CrossRef - Lauritano, C., &Ianora, A. (2016). Marine Organisms with Anti-Diabetes Properties. Marine Drugs, 14(12), 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/md14120220

CrossRef - Agrawal, S., Samanta, S., &Deshmukh, S. K. (2022). The antidiabetic potential of endophytic fungi: Future prospects as therapeutic agents. Biotechnology and applied biochemistry, 69(3), 1159–1165. https://doi.org/10.1002/bab.2192

CrossRef - Zirari M, Aouji M, Imtara H, Hmouni D, Tarayrah M, Noman OM and El Mejdoub N (2024) Nutritional composition, phytochemicals, and antioxidant activities of Abiesmarocana Trab. needles. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 8:1348141. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2024.1348141

CrossRef - Alaa M. Altaie, Mohammad G. Mohammad, Mohamed I. Madkour, Sarra B. Shakartalla, ManjuNidagodu Jayakumar, MS, Aghila Rani K.G., Rabih Halwani, R. Samsudin, Rifat A. Hamoudi, The Essential Role of 17-Octadecynoic Acid in the Pathogenesis of Periapical Abscesses. Basic ResearchVolume 49, Issue 2p169-177.e3February 2023.

CrossRef - Jerez, S., Sierra, L., & de Bruno, M. P. (2012). 17-Octadecynoic acid improves contractile response to angiotensin II by releasing vasocontrictor prostaglandins. Prostaglandins & other lipid mediators, 97(1-2), 36–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2011.07.008

CrossRef - Zou AP, Ma YH, Sui ZH, et al. Effects of 17-octadecynoic acid, a suicide-substrate inhibitor of cytochrome P450 fatty acid omega-hydroxylase, on renal function in rats. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1994 Jan;268(1):474-481. PMID: 8301590

CrossRef - A. TajickGhanbari H. SeidMohammadkhani* V. Babaeizad. Identification of some secondary metabolites produced by four Penicillium species. MycologiaIranica 1(2): 107 – 113, 2014.

- Basavarajappa, D.S.; Niazi, S.K.; Bepari, A.; Assiri, R.A.; Hussain, S.A.; Muzaheed; Nayaka, S.;Hiremath, H.; Rudrappa, M.; Chakraborty, B.; et al. Efficacy of Penicilliumlimosum Strain AK-7 Derived Bioactive Metabolites on Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, and Anticancer Activity against Human Ovarian Teratocarcinoma (PA-1) Cell Line. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2480. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11102480.

CrossRef - Sharma D, Pramanik A, Agrawal PK. Evaluation of bioactive secondary metabolites from endophytic fungus Pestalotiopsisneglecta BAB-5510 isolated from leaves of CupressustorulosaD.Don. 3 Biotech. 2016 Dec;6(2):210. doi: 10.1007/s13205-016-0518-3. Epub 2016 Sep 29. PMID: 28330281; PMCID: PMC5042905.

CrossRef - O. Khromykh, Y. V. Lykholat, O. O. Didur, T. V. Sklyar, V. R. Davydov, K. V. Lavrentievа, T. Y. Lykholat, Phytochemical profiles, antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of Actinidiapolygama and A. arguta fruits and leaves. Biosyst. Divers., 2022, 30(1) 39-45.

CrossRef - Agnihotri, S., Wakode, S., & Ali, M. (2012). Essential oil of MyricaesculentaBuch. Ham.: composition, antimicrobial and topical anti-inflammatory activities. Natural product research, 26(23), 2266–2269. https://doi.org/10.1080/14786419.2011.652959

CrossRef - Sundarapandian Subramanian1 , Mohammed Junaid Hussain Dowlath1 , Sathish Kumar Karuppannan1 , Saravanan M2 , Kantha Devi Arunachalam. Effect of Solvent on the Phytochemical Extraction and GC-MS Analysis of Gymnemasylvestre. Pharmacogn J. 2020; 12(4): 749-761

CrossRef - Chetehouna S, Derouiche S, Réggami Y, Boulaares I, Frahtia A. Gas Chromatography Analysis, Mineral Contents and Anti-inflammatory Activity of Sonchusmaritimus. Trop J Nat Prod Res. 2024; 8(4):6787-6798.

- Techaoei, S., Jirayuthcharoenkul, C., Jarmkom, K., Dumrongphuttidecha, T., &Khobjai, W. (2020). Chemical evaluation and antibacterial activity of novel bioactive compounds from endophytic fungi in Nelumbonucifera. Saudi journal of biological sciences, 27(11), 2883–2889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.08.037.

CrossRef - Shafiquzzaman Siddiquee1*, Bo Eng Cheong1, Khanam Taslima2, Hossain Kausar3 and MdMainul Hasan. Separation and Identification of Volatile Compounds from Liquid Cultures of Trichodermaharzianum by GC-MS using Three Different Capillary Columns. Journal of Chromatographic Science 2012;50:358–367

CrossRef - Rahuman, A. A., Gopalakrishnan, G., Ghouse, B. S., Arumugam, S., & Himalayan, B. (2000). Effect of Feronia limonia on mosquito larvae. Fitoterapia, 71(5), 553–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0367-326x(00)00164-7

CrossRef - Mishra V, Tomar S, Yadav P, Vishwakarma S, Singh MP. Elemental Analysis, Phytochemical Screening and Evaluation of Antioxidant, Antibacterial and Anticancer Activity of Pleurotusostreatusthrough In Vitro and In Silico Approaches. Metabolites. 2022 Aug 31;12(9):821. doi: 10.3390/metabo12090821. PMID: 36144225; PMCID: PMC9502197.

CrossRef - Muthukrishnan S, Prakathi P, Sivakumar T, Thiruvengadam M, Jayaprakash B, Baskar V, Rebezov M, Derkho M, Zengin G, Shariati MA. Bioactive Components and Health Potential of Endophytic Micro-Fungal Diversity in Medicinal Plants. Antibiotics (Basel). 2022 Nov 2;11(11):1533. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11111533. PMID: 36358188; PMCID: PMC9686567.

CrossRef - Sympli H. D. (2021). Estimation of drug-likeness properties of GC-MS separated bioactive compounds in rare medicinal Pleione maculatausing molecular docking technique and SwissADME in silico tools. Network modeling and analysis in health informatics and bioinformatics, 10(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13721-020-00276-1

CrossRef - Nathiya S., Kumar B. S., Devi K. Phytochemical screening and gc-ms analysis of cardiospermumhalicacabum l. leaf extract. International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development . 2018;2(5):512–516. doi: 10.31142/ijtsrd15849.

CrossRef - Mallikadevi T., Paulsamy S., Jamuna S., Karthika K. Analysis for phytoceuticals and bioinformatics approach for the evaluation of therapetic properties of whole plant methanolic extract of mukiamaderaspatana (l.) m.roem (cucurbitaceae)- a traditional medicinal plant in western districts of tamilnadu, i. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research . 2012;5:163–168.

- Priya V., Jananie R. K., Vijayalakshmi K. GC/MS determination of bioactive components of Trigonellafoenumgrecum. Journal of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Research .2011;3:35–40.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.