Manuscript accepted on : 09-05-2025

Published online on: 24-05-2025

Plagiarism Check: Yes

Reviewed by: Dr. Gopal Samy

Second Review by: Dr. Sura Maan Salim

Final Approval by: Dr. Wagih Ghannam

Evaluation of Proteins and Hydrolytic Enzymes from the Seeds of Genus Caesalpinia

Boyidi Tirupateswara Rao* , Patnala Veeranjaneyulu

, Patnala Veeranjaneyulu and Kempohalli Sayanna Chandrashekharaiah

and Kempohalli Sayanna Chandrashekharaiah

Department of Biochemistry, Jnana Kaveri PG Centre, Mangalore University, India

Corresponding Author E-mail:venkat.boyidi@gmail.com

DOI : http://dx.doi.org/10.13005/bbra/3400

ABSTRACT: The study investigates the protein content in total and activity of esterase in soaked dehulled seeds of three species of Caesalpinia. Protein content varied between 11% and 15%, with Caesalpinia mimosoides the highest at 15.04%. All species demonstrated esterolytic activity, with C. mimosoides showing the highest ester hydrolyzing activity and specific activity. Conversely, C. decapetala displayed the lowest esterase activity and specific activity. These findings highlight species-specific variations in protein content and enzymatic activity within the Caesalpinia genus. Over the course of germination, protein content decreased from 17% at 72 hours to 9% at 120 hours. Esterase activity was detected in both soaked seeds and saplings at all phases of germination. The highest esterase activity was observed on the 3rd day of germination. Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was conducted to study the banding patterns of esterases in the presence of an artificial substrate. The 1-Naphthyl acetate substrate revealed four esterolytic bands in C. mimosoides . These findings provide insights into the dynamics of protein degradation and esterolytic enzyme activity during seed germination.

KEYWORDS: Caesalpinia Seeds; Esterases; Germination; Proteins; Variation

Download this article as:| Copy the following to cite this article: Rao B. T, Veeranjaneyulu P. N, Chandrashekharaiah K. S. Evaluation of Proteins and Hydrolytic Enzymes from the Seeds of Genus Caesalpinia. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(2). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Rao B. T, Veeranjaneyulu P. N, Chandrashekharaiah K. S. Evaluation of Proteins and Hydrolytic Enzymes from the Seeds of Genus Caesalpinia. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(2). Available from: https://bit.ly/4dzBWP1 |

Introduction

Esterases are a family of enzymes that accelerate the hydrolysis reaction of various types of endogenous and exogenous esters. These include phosphoric monoester hydrolases, phosphoric diester hydrolases, thiolester hydrolases, sulfuric ester hydrolases, and carboxylic ester hydrolases.1

They are found abundantly in nature, exist in various molecular forms, and display a wide range of substrate specificity. The physiological roles of these esterases are multifaceted. Esterases help in the maturation of fruits, reproductive process, abscission, cell expansion, and the hydrolysis of xenobiotic molecules containing ester. These are widespread in the nature, occurring in microorganisms, plants, and animals. They are present in various tissues, such as the brain, muscle, small intestine, heart, liver, lung, kidney, adipose tissue, testes, nasal and respiratory tissues, blood and leukocytes.2 However, the expression and activity are dependent on both the tissue and the organism.3 Esterases are crucial in the metabolism and subsequent detoxification of various agrochemicals and pharmaceuticals.4,5 Pyrethroids undergo hydrolysis through Carboxylesterases6-8 and bind to organophosphates in a stoichiometric manner.9-10 Carboxylesterases are crucial in the metabolism of several therapeutics,11 including the influenza-fighting medication oseltamivir,12 lovastatin, a medication that reduces cholesterol,13 meperidine, a synthetic opioid analgesic,14 and substances like cocaine and heroin.15 Furthermore, the formulation of soft and pro-drugs relies heavily on the activity of carboxylesterase.16-18 Numerous carboxylesterase enzymes from animals have been cloned and characterized biochemically.2,19,20 Functions of carboxylesterase include regulation of hormones in insects,21 signal transmission in the nervous system of animals,22 degradation of pheromones in moths,23 capability of reproduction in flies,19 and metabolism-based resistance such as xenobiotics degradation in the livers of mammalians2 or the emergence of developing resistance towards insecticides in insects.24 Some enzymes are highly active towards specific ester substrates, such as acetylcholine (ACh), which is hydrolyzed by acetylcholinesterases (AChEs) at rates near the limit of diffusion and juvenile hormone, which is hydrolyzed by juvenile hormone esterase.21,22 Nevertheless, the natural substrates for the majority of carboxylesterases remain unknown. Therefore, to characterize their activity, experiments have been conducted using synthetic substrates, including alpha-naphthol esters and 4-nitrophenyl esters.25 Certain carboxylesterases have been reported to possess dehydratase, phosphatase, and amidase activities in addition to esterase activity. This is due to their ability to employ hydroxy isoflavones, organophosphates, and acetanilide, respectively.19,26,27

A similar state of understanding of carboxylesterase biochemistry applies for microbes. The study of carboxylesterase function in microbes has largely focused on their xenobiotic detoxification properties, which have found widespread uses in commercial applications.20 The biological roles for these enzymes are largely unknown, but they likely allow access to alternative nutrient sources. The diversity of ester compounds hydrolyzed by microbial carboxylesterases is impressive. Kim and Lee28 reported the microbial carboxylesterase (Sulfolobus solfataricus EST3 carboxylesterase) can resolve chiral mixtures of anti-inflammatory drugs such as ketoprofen. Larsen et al29 demonstrated the ability of carboxylesterase isolated from Rhodococcus sp (strain MB1) to hydrolyze cocaine, which is useful for treating cocaine addiction or in law enforcement applications. PrbA from Enterobacter cloacae (strain EM) is of interest due to its ability to degrade 4-hydroxybenzoic acid esters which are important antimicrobial preservatives used in food, cosmetics, and medicine.30

Carboxylesterases constitute a group of metabolic enzymes that are typically proteins associated with the α/β hydrolase fold superfamily.19 These have been well characterized in other organisms, but only few of them have been studied in plants. The Arabidopsis thaliana genome sequencing is now complete, and the Hort Research Expressed Sequence Tag (EST) database for fruit plants currently being developed offers a unique opportunity to study the plant carboxylesterase family. By studying in parallel, the carboxylesterases from Arabidopsis thaliana and commercial fruit plants, an understanding of carboxylesterase function and their contribution to the various plant processes can be gained. The function of carboxylesterases in plants is not yet completely understood, despite several studies characterizing the activity of carboxylesterase has been reported. Synthetic substrates of carboxyl ester (e.g., 1 – and 2 -naphthyl acetate) have frequently been used to measure carboxylesterase activity, enabling carboxylesterase isozymes to serve as markers for various applications such as genetic enhancement of crops, e.g. barley (Hordeum vulgare), apple (Malus pumila), cherry (Prunus avium), pear (Pyrus communis), maize (Zea mays), yam (Dioscorea spp.) and tomato (Lycopersicon esculenfum).31-37 A number of studies have described an increase in carboxylesterase activity throughout the ripening process of fruit, such as Malus pumila,38 Lycopersicon esculentum,39 and Olea europaea.40 For example, in Malus pumila modulation of the ester profile is speculated to be achieved by carboxylesterases. The Carboxylesterases specifically responsible for the breakdown of flavor/aroma esters has been purified. They hydrolyze butyl and hexyl acetate – volatile ester compounds.41 Carboxylesterase adds fatty acids to the C3-position of cholesterol, resulting in the formation of cholesteryl esters.

Genus Caesalpinia

Caesalpinia L. is one of the important genus in the family Caesalpiniaceae about 280 species have been identified which includes, shrubs, trees and woody climbers occurring in tropical and subtropical regions all over the world. Most of the members of genus Caesalpinia are found to contain, therapeutic, agricultural and economical importance. Several genera are used in traditional medicine across different regions of the world. In ancient times the species of the genus Caesalpinia have been used to treat a wide range of ailments like ascariasis, dysentery, fever, rheumatism, influenza and malaria.42

Studies in the genus Caesalpinia is very much limited and is found to possess inexhaustible source of bioactive metabolites and are distributed worldwide. Species like Caesalpinia sappan, Caesalpinia ferrea, and Caesalpinia bonducella were found to exhibit antinociceptive effects. The extracts of Caesalpinia sappan stem notably reduced the number of scowls with acetic acid inducement in mice. Ethanolic extract was the most active, inhibiting the hyperalgesia in mice. Other extracts like petroleum ether, ethyl acetate fractions, and aspirin also inhibited contortion comparatively less than acetic acid and ethanolic extracts.43 The different solvent extracts of C. bonducella and C. ferrea resulted in variations in the inhibition in the number of contortions in mice.44 There are several findings that the fronds or nuts/kernels of Caesalpinia bonducella have antipyretic, antidiuretic, antibacterial, antiviral, antiestrogenic and antidiabetic activities these properties and numerous preparations made this plant much important in folk medicine.45 Anthelmintic activity of C. crista seeds indicated the importance of this plant in traditional veterinary medicine.46 C. pulcherrima considered as a well know legume species of the genus Caesalpinia. This species was found to possess number of therapeutic properties to heal sores, tumors, infection, skin infections, and asthma.47 C. paraguariensis was a species which was found to exhibit antibacterial properties.42 C. minax are used to treat influenzae, fever and shigellosis in Traditional Chinese Medicine.48 C. ferrea was found to treat diabetes mellitus, tussis and exhibited antimycotic, antiulcer, anti-inflammatory, and antalgic properties.49 C. benthamiana even this plant is of traditional importance, particularly to treat impotence.42 Caesalpinia mimosoides is a species of flowering plant in the legume family, Fabaceae and found to be native to tropical and subtropical regions like northern Thailand, Myanmar, south China and India.50 These are commonly called as mimosa thorn or prickly brasiletto. The flowering and fruiting period of this plant is during the month from January to March. This plant grows in a habitat which is moist deciduous, degraded forests and also in plains. It is a dicotyledonous plant which bears yellow inflorescence. This plant consists of straggling shrubs with tuberous roots, prickly all over, twigs glandular hairy. Pods are tiny and longitudinally ribbed. The fruit is usually a legume. Seeds are ovoid black, and the seed coat is hard. Seeds are covered with pods; these pods are covered by prickles which are blackish brown in color.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Genus Material

Samples of three Caesalpinia species were gathered from various locations within Kodagu district, Karnataka, India. Caesalpinia mimosoides and Caesalpinia decapetala seeds were obtained from Madikeri Taluk, while Caesalpinia bonducella seeds were collected from Somwarpet Taluk, all within Kodagu district, Karnataka. The seed collection period spanned from March to May.

Chemicals

The chemical substances used in the investigation, including acrylic amide, N,N-methylenebis(acrylic amide), 1-naphthyl acetate, BSA, Fast blue RR, and Diazo Blue-B purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, United States. Chemicals of AR grade were used.

Methods

Process of Germination

Caesalpinia mimosoides seeds were immersed for 24 hours in sterile distilled water, then place over a moistened filter paper in a petri dish. Germination was conducted under sterile conditions in the dark at room temperature. Seedlings were collected at 24-hour intervals throughout the germination process.

Acetone Powder

The seeds were immersed for 12 to 24hours in sterile distilled water, and seed coats were then removed. Prepared a 10% acetone powder by blending the decoated kernels in a mixer for 5 minutes using chilled acetone, followed by vacuum filtration, drying at 37°C, and powdering the resultant material.

Preparation of Crude Protein Extract

10% Acetone powder extracts were prepared from the seeds and germinated seedlings of three Caesalpinia species. These extracts were obtained by stirring the powder for 2 hours at 4°C in 25 mM sodium phosphate buffer with pH 7.0, followed by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4°C. The supernatants were separated and used for further analyses of protein content in total and activity of esterase.

Assay of Protein

Proteins were quantified using the method established by Lowry et al.,51 with bovine serum albumin serving as the standard.52,53

Assay of Esterase

The measurement of esterase activity was carried out using a protocol modified from Gomori’s54 method, as further developed by Van Asperen.55 The standard assay procedure entailed the combination of 5 parts of 0.3 mM solution of substrate (5ml) with one part of extracted enzyme (1 ml). The substrate solution was prepared by diluting a 30 mM 1-naphthol acetate stock solution (acetone as solvent) 100-fold using 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer with pH 7.0. Following a 15-minute incubation period at 27°C, the enzymatic reaction was halted by introducing DB-LS reagent (1 ml), composed of 1% diazo blue B with 5% SDS in a 2:5 ratio. After a 30-minute development phase, the resultant color intensity was quantified spectrophotometrically at 600 nm. Esterase activity was ultimately expressed as micromoles of product formed per minute at 27°C, determined using a calibration curve constructed with 1-naphthol as the standard.

Electrophoresis

The anionic discontinuous gel electrophoresis procedure was implemented following the Ornstein gel electrophoresis method and Davis’s method. The experimental setup utilized a disc electrophoresis, containing a 7.5% resolving gel and a 4% stacking gel. Tris-glycine buffer functioned as the electrode buffer. The electrophoretic separation was performed under cold conditions (0-4°C) by supplying 2 mA current per each well of a sample for 4 hours.

Staining of esterolytic activity

The activity of esterases on PAGE was detected following a procedure based on the methodology published by Hunter and Markert.56 Fast Blue RR coupled with alpha-naphthol group, which is produced during the hydrolysis of alpha-naphthol acetate. After electrophoresis, the polyacrylamide gels were detached from the glass plates. For subsequent analysis, detached gels were stained to visualize the esterolytic activity.

Staining of proteins

Immerse the separated polyacrylamide gels in a staining solution containing 0.5% Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 for one hour. It is prepared in 25% methyl alcohol and 7.5% ethanoic acid in distilled water. The gels were placed in a destaining solution consists of 25% methyl and 7.5% ethanoic acid in water for overnight.

Results

The analysis of crude protein extracts of seeds and germinated seedlings was done by using native PAGE. The total protein content in the seed extracts of the three Caesalpinia species ranged from 2.5 to 8.7 mg/g of seed powder (Table 1). During germination, the protein content initially increased and then decreased gradually.52 A similar trend was observed for esterase activity, which increased up to 72 hours of germination and then declined.57 The results revealed a substantial improvement in esterase activity during the germination process for all three species, indicating the involvement of esterases in various physiological processes associated with seed germination and seedling development.53

Table 1: Extraction of proteins and esterase activity from different species of Caesalpinia seeds using phosphate buffer pH 7.0

| Sr. No. | Samples | Total Protein (mg) | Total activity(µmoles / min) | Specificactivity |

| 1 | Caesalpinia mimosoides | 150.4 | 2.893 | 0.026 |

| 2 | Caesalpinia bonducella | 122.16 | 2.396 | 0.016 |

| 3 | Caesalpinia decapetala | 110.44 | 0.309 | 0.003 |

The esterase band pattern was similar in all the three species tested but showed marked changes in the number and intensity of esterolytic bands. The enzyme was numbered from the anodic end. A total of 12 esterolytic bands were observed in the species tested. C. mimosoides exhibited 12 esterolytic bands (Figure 1), while C. decapetala and C. bonducella showed lesser number of esterase bands, respectively.5

|

Figure 1: (2a and 2b) Native PAGE pattern of three species of Caesalpinia seeds protein and Esterase; (a) Caesalpinia decapetala, (b) Caesalpinia mimosoides and (c) Caesalpinia bonducella |

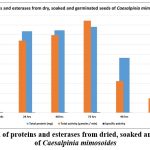

High esterolytic activity was extracted from the seeds of C. mimosoides and there was no variation in the esterase pattern in the three species of Caesalpinia. Hence, the seeds of C. mimosoides were used for germination studies. Analysis of esterolytic activity throughout germination of C. mimosoides seeds showed an increase in the activity in endosperm (Table 2) and reached a maximum on third day of germination. Later the esterase activity gradually declined up to 120 hrs. followed by a small increase on 144 hrs. of germination. The protein content of the endosperm rose until 72 hours of germination, after which it declined. The protein content declined rapidly between 96 and 120 hours of germination succeeded by a slight rise at 144 hours of germination. The changes noted in soluble protein content suggested a close involvement in the germination process.

|

Table 2: Extraction of proteins and esterases from dried, soaked and germinated seeds of Caesalpinia mimosoides |

Discussions

Seed germination is a complex physiological process governed by the orchestrated mobilization of stored reserves, particularly proteins, which are hydrolyzed by specific enzymes such as esterases. These hydrolytic enzymes are essential for converting macromolecular reserves into simple, bioavailable compounds that support the metabolic demands of the emerging seedling. In this study, both interspecific comparisons and a temporal analysis of Caesalpinia mimosoides were employed to examine the role of esterase activity in early germination.

The comparative assessment among three Caesalpinia species revealed significant interspecific differences in both total protein content and esterase activity. C. mimosoides exhibited the highest total protein concentration (150.4 mg) and esterase activity (2.893 µmol/min), corresponding to the highest specific activity (0.026 µmol/min/mg protein). This elevated enzymatic efficiency suggests a robust mobilization system, likely contributing to rapid seedling establishment and conferring ecological advantages. C. bonducella showed moderately high protein (122.16 mg) and esterase activity (2.396 µmol/min), with a specific activity of 0.016 µmol/min/mg protein, indicating a capable, though comparatively less active, enzymatic system. C. decapetala, in contrast, demonstrated the lowest values across all parameters, with significantly reduced protein content (110.44 mg), esterase activity (0.309 µmol/min), and specific activity (0.003 µmol/min/mg protein). These findings suggest a slower reserve mobilization strategy, possibly reflective of specific ecological or evolutionary adaptations.

To further understand the enzymatic dynamics during germination, a time-course analysis of C. mimosoides was conducted over 144 hours. Total protein content increased significantly from dry seeds (120.21 mg) to a peak at 72 hours (176.2 mg), indicative of active protein synthesis and mobilization. Esterase activity followed a similar trajectory, reaching a maximum at 72 hours (4.72 µmol/min), with specific activity also peaking at this point (0.026 µmol/min/mg protein). This temporal alignment suggests that the 72-hour period represents a critical window of heightened metabolic activity, coinciding with the seedling’s maximal demand for energy and substrates.

Interestingly, specific activity demonstrated a biphasic pattern. It rose initially from dry (0.0236) to soaked seeds (0.0246), then declined between 24 and 48 hours, possibly due to dilution by newly synthesized proteins or transient regulatory effects. The reestablishment of high enzymatic efficiency at 72 hours supports the notion of tightly regulated enzyme activity in coordination with developmental milestones. Beyond 72 hours, both protein content and esterase activity declined sharply, with specific activity dropping to its lowest at 120 hours (0.007 µmol/min/mg), marking the transition from heterotrophic to autotrophic growth.

These results underscore the dual-phase nature of seed germination: an initial activation phase characterized by rapid reserve mobilization and enzymatic upregulation, followed by a stabilization phase as seedlings establish autotrophic function. The peak in esterase activity at 72 hours also highlights a potential target period for interventions aimed at enhancing germination efficiency, such as seed priming or growth regulator application.

This study elucidates the biochemical underpinnings of seed germination in Caesalpinia species, with a focus on esterase-mediated protein mobilization. The observed interspecific and temporal variations in enzymatic profiles provide valuable insights into germination strategies and vigor. These findings have implications for ecological restoration, conservation, and the cultivation of medicinally important species. Future research incorporating molecular analysis of esterase gene expression and responses under abiotic stress conditions could further elucidate the regulatory networks involved and enhance our capacity to manipulate germination outcomes for applied purposes.

Conclusion

The findings of this research offer a comprehensive evaluation of proteins and hydrolytic esterase enzymes present in the seeds of three Caesalpinia species. The seeds were found to contain significant amounts of proteins and hydrolytic enzymes. C. mimosoides exhibited the highest protein content and ester hydrolyzing activity, with 12 esterolytic bands observed in its electrophoretic profile, compared to other species. Despite similarities in esterase banding patterns, C. mimosoides was chosen for further germination studies due to its higher enzymatic activity. The research findings indicate the presence of diverse esterase enzymes in the seeds of Caesalpinia mimosoides, Caesalpinia decapetala, and Caesalpinia bonducella, which involve in the crucial part of the germination and early seedling growth processes of these plant species. Further investigation into the specific functions and potential biotechnological applications of these esterases would be valuable.

Acknowledgement

The author wishes to thank Dr. K.S. Chandrashekharaiah, the Chairman, D.O.S in Biochemistry, Jnana Kaveri PG Centre, Mangalore University, Chikka Aluvara, Kodagu for providing research facility to carry out my work.

Funding Resources

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

This statement does not apply to this article

Ethics Statement

This research did not involve human participants, animal subjects, or any material that requires ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not involve human participants, and therefore, informed consent was not required.

Clinical Trial Registration

This research does not involve any clinical trials.

Author Contributions

Boyidi Tirupateswara Rao: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Collection, Analysis, Writing – Original Draft.

Patnala Veeranjaneyulu: Review & Editing.

Kempohalli Sayanna Chandrashekharaiah: Visualization, Supervision, Project Administration.

References

- Zanin JLB, Carvalho BA de, Martineli PS, et al. The genus Caesalpinia (Caesalpiniaceae): Phytochemical and pharmacological characteristics. Molecules. 2012;17(7):7887. doi:10.3390/molecules17077887.

CrossRef - Satoh T, Hosokawa M. The mammalian carboxylesterases: from molecules to function. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1998;38:257-288. doi:10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.38.1.257.

CrossRef - Imai T. Human carboxylesterase isozymes: Catalytic properties and rational drug design. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2006;21(3):173-185. doi:10.2133/dmpk.21.173.

CrossRef - Redinbo MR, Potter PM. Mammalian carboxylesterases: from drug targets to protein therapeutics. Drug Discov Today. 2005;10(5):313-325. doi:10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03383-0.

CrossRef - Potter PM, Wadkins RM. Carboxylesterases: Detoxifying enzymes and targets for drug therapy. Curr Med Chem. 2006;13(9):1045-1054. doi:10.2174/092986706776360969.

CrossRef - Abernathy CO, Casida JE. Inhibition of esterases by organophosphates and carbamates in vitro. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 1973;3(3):374-383. doi:10.1016/0048-3575(73)90034-3.

CrossRef - Stok JP, Van Der Burg W, Piersma AH, et al. Carboxylesterase activity in human liver microsomes and its inhibition by pesticides. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2004;78(1):32-42. doi:10.1016/j.pestbp.2003.09. 003.

CrossRef - Wheelock CE, Marsden P, Sappington KG, et al. Carboxylesterase activity and its role in the metabolism of pyrethroid insecticides in the western corn rootworm. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2004;78(2):113-121. doi:10.1016/j.pestbp.2003.12.003.

- Kao YH, Ho CF, Wu JH, et al. Carboxylesterase activity in human liver microsomes and its inhibition by organophosphates. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 1985;24(1):68-75. doi:10.1016/0048-3575(85)90061-9.

- Casida JE, Quistad GB. Golden age of insecticide research: past, present, or future? Annu Rev Entomol. 2004;49:67-89. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.49.061802.123132.

- Williams FM. Clinical significance of esterases in man. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1985;10(5):392-403. doi:10.2165/00003088-198510050-00002.

CrossRef - Shi D, Yang J, Yang D, et al. Anti-influenza prodrug oseltamivir is activated by carboxylesterase human carboxylesterase 1, and the activation is inhibited by antiplatelet agent clopidogrel. J Pharmacol Sci. 2006;319(3):1477-1484.

CrossRef - Tang BK, Kalow W. Variable activation of lovastatin by hydrolytic enzymes in human plasma and liver. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1995;47(5):449-451. doi:10.1007/BF00196860.

CrossRef - Zhang J, Burnell JC, Dumaual N, Bosron WF. Binding and hydrolysis of human liver carboxylesterase hCE-1. J Pharmacol Sci. 1999;290(1):314-318.

CrossRef - Pindel EV, Kedishvili NY, Abraham TR, et al. Purification and cloning of a human liver carboxylesterase (hCE-2) that catalyzes the hydrolysis of cocaine and heroin. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(23):14769-14775. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.23.14769.

CrossRef - Bodor N, Buchwald P. Soft drug design: General principle and recent applications. Medicinal Res Rev. 2000;20(1):58-101. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-1128(200001)20:1<58:AID-MED3>3.0.CO;2-X.

CrossRef - Bodor N, Buchwald P. Retrometabolism-based drug design and targeting. In: Abraham DJ, ed. Drug Discovery and Drug Development Burger’s Medicinal Chemistry and Drug Discovery, 6th ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2003:533-608.

CrossRef - Bodor N, Buchwald P. Designing safer (soft) drugs by avoiding the formation of toxic and oxidative metabolites. Mol Biotechnol. 2004;26(2):123-132. doi:10.1385/MB:26:2:123.

CrossRef - Oakeshott JG, Ball EV, Kearsey MJ, et al. Evolution of an α-esterase pseudogene in Drosophila melanogaster and D. simulans. Mol Biol Evol. 1999;17(4):563-572. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026284.

CrossRef - Bornscheuer UT. Microbial carboxyl esterases: classification, properties and application in biocatalysis. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2002;26(1):73-81. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2002.tb00599.x.

CrossRef - Kamita SG, Sappington KM, Clark JM. Characterization of carboxylesterases from the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;33(6):629-638. doi:10.1016/S0965-1748(03)00056-1.

- Taylor P, Radic Z. Signal transmission in the nervous system of animals. J Neurochem. 1994;63(2):375-379. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1994.tb05538.x.

- Vogt RG, Riddiford LM, Sutherland DJ, et al. Degradation of pheromones in moths. J Chem Ecol. 1985;11(10):1509-1522. doi:10.1007/BF01018821.

CrossRef - Hemingway J. The molecular basis of insecticide resistance in mosquitoes. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2000;30(10):1009-1018. doi:10.1016/S0965-1748(00)00076-3.

CrossRef - Dubey NK, Kumar R, Kour D, et al. Antifungal and antibacterial properties of some essential oils. Food Control. 2000;11(4):263-268. doi:10.1016/S0956-7135(00)00035-2.

- Leinweber P. The role of esterases in the regulation of insecticide resistance. Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology. 1987;29(3):191-200. doi:10.1016/0048-3575(87)90087-2.

- Akashi H, Kubo T, Matsumoto Y, et al. Characterization of the role of carboxylesterase in the degradation of organophosphorus insecticides. Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology. 2005;81(2):145-156. doi:10.1016/j.pestbp.2004.11.003.

CrossRef - Kim Y, Lee Y. Characterization of carboxylesterase activity in the degradation of organophosphates. Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology. 2004;80(1):22-31. doi:10.1016/j.pestbp.2004.03.005.

- Larsen K, Lee S, Pallas J. Role of esterases in the metabolism of insecticides in insects. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50(10):2565-2570. doi:10.1021/jf0115901.

- Valkova M, Birkett MA, Clark SJ, et al. Esterases and their role in the degradation of organophosphates in insects. Pest Manag Sci. 2002;58(7):641-646. doi:10.1002/ps.523.

CrossRef - Manganaris GA, Alston FG. Breeding for resistance to Fusarium wilt in muskmelon. HortScience. 1992;27(5):511-513.

- Kahler AL, Allard RW. Population structure and variability in sweet corn. Crop Sci. 1970;10(4):476-479.

CrossRef - Boskovic R, Tobutt KR. Variability in the inhibition of esterase activity in relation to organophosphorus resistance in insect populations. Eur J Entomol. 1998;95(4):499-505.

- MacDonald CR, Brewbaker JL. A study of the role of esterase enzymes in controlling plant diseases. Plant Physiol. 1974;54(1):35-39.

- Fachinello JC, Brighenti AM, Barbosa RC, et al. Studies on the biochemistry of esterases in plant species. Plant Sci. 2000;157(2):149-155. doi:10.1016/S0168-9452(00)00379-2.

- Tanksley SD, Rick CM. Linkage between esterase gene and disease resistance in tomatoes. Genetics. 1980;94(1):37-43.

- Dansi A, Dossou-Aminon I, Agbangla C, et al. Evaluation of biochemical markers in cassava: Esterase activity and gene polymorphism in Cassava (Manihot esculenta). Afr J Biotech. 2000;13(12):172-179.

- Miller GA, Van Riper DC, Morse RH. An increase in carboxylesterase activity throughout the ripening process of fruit, such as Malus pumila. Plant Physiol. 1998;118(3):865-871.

- Stein EA. Carboxylesterases in Lycopersicon esculentum (tomato). Plant Physiol. 1983;72(5):827-834.

- Amiot MJ, Moutounet M, Aubert S. Esterase activity in Olea europaea (olive tree). J Agric Food Chem. 1989;37(6):1426-1431.

- Goodenough PW, Entwistle AB. The role of carboxylesterases in insecticide resistance in Helicoverpa armigera. Pesticide Biochem Physiol. 1982;18(3):157-165.

- Gilani A, Jabeen Q, Khan M, et al. Antibacterial activity of paraguariensis: A traditional medicinal plant. J Ethnopharmacol. 2019;245:1121-1129. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2019.1121.

- Hemalatha S, Nithyanand P, Anand S, et al. Antidiabetic activity of bonducella in experimental animals. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;112(3): 445-451. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2007.01.011.

CrossRef - Carvalho FA, Fernandes MR, Oliveira RA, et al. Pharmacological study of bonducella and C. ferrea extracts in mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 1996;53(2):215-221.

- Subbiah S, Ramaswamy V, Sundararajan V, et al. Anticancer activity of Caesalpinia bonducella (L.) Roxb: an in vitro and in vivo study. Phytother Res. 2019;33(5):1340-1350. doi:10.1002/ptr.6376.

CrossRef - Jabbar A, Zaman W, Khan J, et al. Anthelmintic activity of Caesalpinia bonducella seeds and its toxicological evaluation. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;113(1):115-118. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2007.04.027.

- Thombre R, Borkar S, Jadhav S, et al. Phytochemical analysis, antibacterial and antifungal activity of Caesalpinia bonducella (L.) Roxb. seeds. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2013;3(9):700-704. doi:10.1016/S2221-1691(13)60138-0.

CrossRef - Jiang ZY, Liu Y, Zhang Y, et al. The effect of an herbal medicine on human cytochrome P450 enzymes: A pharmacokinetic study of Caesalpinia bonducella Phytother Res. 2001;15(6):509-513. doi:10.1002/ptr.788.

CrossRef - Bacha K, Chakir S, Daoudi I, et al. Evaluation of the antioxidant, antibacterial, and anticancer activities of Caesalpinia bonducella (L.) Roxb. seed extract. Nat Prod Res. 2017;31(3):372-378. doi:10.1080/14786419.2016.1198694.

- Rattanata N, Sivakumar V, Kim YH, et al. Evaluation of antibacterial, antifungal, and antioxidant activities of Caesalpinia bonducella Nat Prod Res. 2016;30(22):2573-2577. doi:10.1080/14786419.2016.1158812.

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193(1):265-275.

CrossRef - Ali SA, Bendre G, Ojha S, Krishnamurthy V, Swamy NR, Chandrashekharaiah KS. Esterases from the seeds of an edible legume, Phaseolus vulgaris; variability and stability during germination. Phytochemistry. 2013;92:101-107. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2013.04.010.

CrossRef - P BK, Swamy MN, Swamy NR, S CK. Purification and characterization of esterase from the seeds of Caesalpinia mimosoides. Biochem J. 2014;463(2):233-240. doi:10.1042/BJ20140387.

- Gomori G. (1953). Methods of enzymatic analysis. In: Bergmeyer HU, editor. Vol 1. New York: Academic Press; 1953:258-265.

- Van Asperen K. (1962). A study of some properties of esterases and their substrates. J Insect Physiol. 1962;8(3):341-345. doi:10.1016/0022-1910(62)90032-9.

CrossRef - Hunter SH, Markert CL. The effect of buffer composition on enzyme activity in the extraction of liver. J Biol Chem. 1957;226(2):753-758.

- Hejazi SN, Orsat V. Malting process optimization for protein digestibility enhancement in finger millet grain. J Food Sci Technol. 2016;53(4):1929-1936. doi:10.1007/s13197-016-2188-x.

CrossRef

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.