Manuscript accepted on : 04-06-2025

Published online on: 10-06-2025

Plagiarism Check: Yes

Reviewed by: Dr. Sonam Sneha

Second Review by: Dr. Vikas Guleria

Final Approval by: Dr. Everaldo Silvino dos Santos

Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Human Feces of Vegetarian and Non-Vegetarians

Anchal Bamal1 and Amar Prakash Garg2*

and Amar Prakash Garg2*

1School of Biotechnology and Life Sciences, Shobhit Institute of Engineering and Technology, Modipuram, Meerut, Uttar Predesh, India.

2 Research and Development Cell, Swami Vivekanand Subharti University, Subhartipuram, Meerut, Uttar Pradesh, India.

Corresponding Author e-mail: amarprakashgarg@yahoo.com

DOI : http://dx.doi.org/10.13005/bbra/3402

ABSTRACT: The human microbiota is currently receiving significant attention, and the studies have shown that the changes to this microbiome can lead to extensive consequences. The gut microbiota’s diversity and composition can be influenced by dietary choices. Human faeces are the solid waste material excreted as the residual product following the digestion of food within the small intestine. This waste contains a significant number of viruses, bacteria, fungi, actinomycetes, and other microorganisms. Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are prevalent and perform a significant function in immunity and metabolism. This study involved the processing of faecal samples from both vegetarian and non-vegetarian sources to isolate various LAB. Lactococcus spp., Bifidobacterium spp., Leuconostoc spp., Lactobacillus spp., Enterococcus spp., and Pediococcus spp. were isolated from both samples, although the percentages differ in each case. In vegetarian samples, Lactobacillus species were predominant (35%), followed by Lactococcus (24%), Bifidobacterium (20%), Enterococcus (9%), Pediococcus (7%), and Leuconostoc (5%). Conversely, non-vegetarian samples showed a higher proportion of Lactobacillus (44%), Leuconostoc (15%) and Enterococcus (18%), with lower percentages of Lactococcus (9%) and Bifidobacterium (7%) while Pediococcus (7%) remained unaffected. The higher population of Bifidobacterium in vegetarian suggest greater happiness of vegetarians than non-vegetarians as the bacterium is known to reduce depression and increase happiness. The processes of isolation, characterisation, and biochemical identification were conducted using Gram's staining, oxidase test, catalase test, and fermentation of sugar. The most effective isolates were determined through the evaluation of various probiotic characteristics, their antimicrobial properties, and their sensitivity to antibiotics. This study highlights the impact of dietary habits on the formation and probiotic functions of microbiota of gut. A diet of vegetarian appears to encourage a higher prevalence and diversity of LAB that display advantageous probiotic traits.

KEYWORDS: Gut microbiota; happy bacteria; Lactic acid bacteria; Non-vegetarian diet; Probiotics; Vegetarian diet

Download this article as:| Copy the following to cite this article: Bamal A, Garg A. P. Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Human Feces of Vegetarian and Non-Vegetarians. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(2). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Bamal A, Garg A. P. Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Human Feces of Vegetarian and Non-Vegetarians. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(2). Available from: https://bit.ly/4n9vkv8 |

Introduction

The human body co-exists with around 1000 diverse bacterial species that contribute to the maintenance of host homeostasis. The gastrointestinal tract (GIT) constitutes a significant distinct habitat for these microbes, primarily comprising beneficial biota such as lactic acid bacteria (LAB). Dysbiosis of the microbial community can lead to compromised gut function and increased illness susceptibility.1 LAB represent a varied collection of microbes characterised by their production of lactic acid as the main by-product of carbohydrate metabolism. LAB are defined as Gram-positive, typically non-motile, non-sporogenic organisms that generate lactic acid as a primary or exclusive outcome of their fermentative processes. They are a collection of rod-shaped, lactic acid-producing, phylogenetically diverse organisms.2 Lactobacilli are commonly found in various natural environments and are often present in fermented foods, including dairy products, beverages, fish, pork, and vegetables, as well as in sewage.3 Certain species are thought to be part of the commensal flora in the human GIT and are utilised as probiotics to combat diseases.4 The significance of LAB as a primary category of probiotics is recognised by the majority of researchers. Recently, a variety of studies have been conducted on the identification of probiotic microorganisms.5 A variety of bacterial and yeast genera are utilised as probiotics, such as Bifidobacterium, Leuconostoc, Pediococcus, Lactobacillus, and Enterococcus. However, the primary species recognised for their probiotic properties include Bifidobacterium spp., Lactobacillus casei, and Lactobacillus acidophilus. These probiotics are defined as “living microorganisms that, when provided in sufficient quantities, offer a health advantage to the host”.6 Probiotics possess significant potential to positively impact the host by altering immune responses and affecting metabolic functions, such as cholesterol assimilation, lactase activity, and vitamin production.7,8 In this study, the Lactobacillus species was isolated from the faeces of human beings having vegetarian and non-vegetarian diets. Vegetarian and vegan diets cultivate distinct microbiota in comparison to omnivorous diets, with only a slight variation observed between vegans and vegetarians.9 Alterations in microbiota composition may result from discrepancies in microorganisms ingested by food, variances in substrates eaten, and fluctuations in transit time through the gastrointestinal tract. A plant-based diet seems advantageous for human health by fostering a more diversified gut microbial ecosystem and an equitable distribution of various species.10,11

Materials and methods

Collection of samples

Total 50 samples were collected from healthy human individuals, 25 each of vegetarian and non-vegetarian, respectively. Only those volunteers were selected who were not on any medication since last 03 months. The vegetarians and non-vegetarians were advised and requested eat respective diets atleast two meals in a day for one month before collection of their samples for research. The samples were collected in a sterile bottle which was provided to the volunteers. The volunteers were also advised and requested not to consume the alcohol as it has the bactericidal activity. The consent form was filled out by all the volunteers.

Isolation of the lactobacilli isolates from faecal samples

The strains of Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) were isolated from faecal samples by weighing 1 gram of the sample that was suspended in 10 mL sterilized 0.85% normal saline to create the stock solution. The samples were serially diluted in 0.85% sterµile normal saline to a dilution of 10-5. A volume of 100 µL from the dilutions of various samples in triplicate (i.e., 10-3, 10-4, 10-5) was spread onto MRS medium plates aseptically and incubated anaerobically at 37±1 ºC for 24- 48 hours in an anaerobic gas chamber.

LAB Enumeration

Subsequent to incubation, the colonies of bacteria were enumerated utilising a digital colony counter, and the CFU/mL were computed employing reference methodology.

Characterisation of Isolates at the Biochemical Level

Isolated bacteria were sub-cultured to get a pure colony. The chosen pure colonies were further processed for biochemical characterisation. Gram staining, catalase test, oxidase test, and sugar fermentation assays were performed to characterise the isolates.

Gram’s staining

A solitary drop of sterilized water was applied to a clean glass slide, and an isolated colony was meticulously chosen from the plate of MRS media and softly blended to form a smear. The prepared smear was carefully fixed with heat and the prescribed protocol for Gram’s staining was followed, and the slide was examined under an oil immersion lens (10x X 100x) of a binocular LED research microscope ( Carl Zeiss).

Catalase Test

The catalase test was conducted for each Gram-positive isolated culture. Catalase is an enzyme synthesised by several microorganisms that catalyses the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide into water and oxygen, leading to the generation of gas bubbles. A 3% hydrogen peroxide solution was meticulously administered to a clean and sterilized glass slide and examined for the formation of bubbles.12

Oxidase Test

All isolates demonstrating negative activity of catalase enzymes were further analysed using the oxidase test. Enzyme, Cytochrome c oxidase is found in multiple bacterial electron transport chains, which catalyses the oxidation of the reagent tetramethyl-phenylenediamine, leading to the production of indophenols that display a purple hue as the final product.13

Sugar fermentation Test

Microorganisms generate an acid or an acid with gas as a by-product during carbohydrate fermentation. The final output may differ depending on the particular microorganisms engaged. All isolates demonstrating Gram-positive traits and negative results for both catalase and oxidase were assessed for this test. Inoculation of each isolate was done in solutions of various carbohydrates (Lactose, Fructose, Glucose, Maltose, Mannitol, Sucrose, and Starch) including inverted Durham tubes and incubated for 48 hours at 37±1℃. The isolates were identified based on their sugar fermentation activity, using Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology.14

Determination of Probiotic Potentials

Following the biochemical characterisation, all test isolates underwent evaluation for their probiotic efficacy through assessments of development at lower pH, varying temperatures, bile salt tolerance, pancreatin tolerance, and antimicrobial and antibiotic resistance.

Growth at low Acidity

The pH level in the human stomach typically falls between 2 and 3. It is commonly understood that the food we consume remains in the stomach for a minimum of 4 hours. For evaluation of the growth of isolated Lactic acid bacteria at low acidity, overnight cultured isolated bacteria were firstly inoculated in MRS broth with acidic pH levels (pH 3.0, 4.0 and 5.0) and incubated for a duration of 0 hours, 2 hours and 4 hours. The test cultures were subsequently inoculated on the plates of MRS agar and incubated at 37±1°C for a duration of 48 hours.15

Growth at different temperatures

The growth of isolates was assessed at various temperatures by inoculating active cultures onto MRS agar plates, which were then incubated under anaerobic conditions at temperatures of 25, 30, 35, and 40°C. The isolates demonstrating optimal growth at both elevated and reduced temperatures underwent additional screening.16

Bile Tolerance

The typical bile concentration found in the human intestine is estimated to be 0.3% (w/v). The duration for which the food we consume remains in the small intestine is approximately 4 hours. Isolates were tested for their resistance to different stress factors. For bile tolerance, 1 mL of test culture (O.D at 600nm using UV-Spectroscopy model-PC based double beam Spectrophotometer 2206- Systonic) was transferred into a fresh broth of MRS media (added with 0.3% bile) which was diluted serially at every 0, 3 and 6 h and 100 µL was spread onto MRS agar plates. The method of plate count was used for observing and enumerating viable colonies, after incubation at 37±1°C for 48 h and expressed in log cfu/mL.17 Tests were performed in triplicate and the survival rate (%) was calculated as follows:

Pancreatin Tolerance

For pancreatin tolerance 1 mL of test cultures (O.D. 1.0 at 600nm) was inoculated into fresh MRS broth with 0.5% pancreatin further diluted serially and from the final dilution of 100 µL was spread onto MRS plates at 0, 3, and 6 hours.18 The feasibility of the isolates was determined by the method of plate count after incubation at 37±1°C for 48 h and expressed in log cfu/mL. The survival rate was calculated with the help of the above formula used for the calculation of the bile salt tolerance.19

Antibiotics Resistance

The isolates demonstrating optimal growth at both elevated and reduced temperatures were assessed for their resistance to standard antibiotics using the Kirby Bauer method. The isolates exhibited a uniform distribution across the complete surface of the MRS agar plates, while the antibiotic discs, featuring different concentrations, were placed on the agar surface and gently pressed into position.20 The plates were allowed to incubate at room temperature for a period of 24 to 48 hours. The isolates that failed to generate the anticipated zone of inhibition surrounding the antibiotic discs, according to the standard chart, were then examined for their antimicrobial activities against common human pathogens.21

Resistance to Human Pathogens

All the isolates that met the specified criteria underwent additional testing for their antimicrobial activities against prevalent pathogens of humans through the agar well diffusion method. The indicator pathogenic microorganisms were distributed across the entire surface of MRS agar plates using a sterile core borer with a diameter of 6 mm. The overnight grown culture of the isolate was inoculated into the wells using micropipettes. The plates were maintained in an upright position for the duration of 24 hours during incubation. Subsequently, the inhibition zone was measured. The isolates that exhibited larger inhibition zones were deemed to possess significant probiotic potential.21,22

Results

A total of 50 human faecal samples (24 each from healthy vegetarian and non-vegetarian diets respectively) were examined in this study. The results indicated a good growth of LAB on MRS agar plates. (Figure 1). A total of 120 colonies were successfully isolated under anaerobic conditions from the collected samples. Total 75 bacterial cultures were isolated from the vegetarian samples and only 45 from the non-vegetarian samples which clearly suggest higher quantity and greater diversity of microbiome in vegetarians. The identification of the isolates was conducted based on their physiological and biochemical characteristics. The identification was done on the basis of fermentation of sugar with the help of the Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. The Colony forming unit /mL varies from the range of 102 to 108 and was counted with the help of the colony counter. The traits of colonies developed on the MRS plates differed across the various samples. As the diet influences the growth of gut microbiota, the MRS plates spread with the vegetarian samples shows the high growth of the LAB isolates whereas the plates spread with the non-vegetarian stool sample having less count of colonies and the types of colonies on the spread plates were also decreased (Table 1).

|

Figure 1: (a) MRS plate showing the growth of LAB from vegetarian samples whereas (b) shows the growth of LAB from non-vegetarian samples. |

Table 1: Average number CFU/mL of LAB isolated from the human faecal samples using Standard Plate Count (S1-S10 Vegetarian samples and NV1-NV10 non-vegetarian samples). Each figure is an average of three independent replicates.

| Sample No. | No. of CFU/mL from vegetarian samples | Sample No. | No. of CFU/mL from vegetarian samples | Sample No. | No. of CFU/mL from non-vegetarian samples | Sample No. | No. of CFU/mL from non-vegetarian samples | |

| S1 | 7.4×107 | S14 | 8.6×107 | NV1 | 4.2×104 | NV14 | 4.7×105 | |

| S2 | 5.9×108 | S15 | 3.9×104 | NV2 | 3.5×103 | NV15 | 6.3×103 | |

| S3 | 4.6×107 | S16 | 6.7×104 | NV3 | 2.8×102 | NV16 | 2.8×103 | |

| S4 | 6.6×106 | S17 | 4.4×103 | NV4 | 6.3×103 | NV17 | 3.5×104 | |

| S5 | 5.8×106 | S18 | 7.6×105 | NV5 | 4.2×103 | NV18 | 5.8×105 | |

| S6 | 6.3×107 | S19 | 8.1×108 | NV6 | 8.7×104 | NV19 | 7.2×102 | |

| S7 | 7.2×108 | S20 | 3.3×106 | NV7 | 7.5×105 | NV20 | 8.1×104 | |

| S8 | 3.9×107 | S21 | 8.8×108 | NV8 | 3.2×103 | NV21 | 7.5×102 | |

| S9 | 4.2×106 | S22 | 2.8×108 | NV9 | 4.6×105 | NV22 | 2.2×103 | |

| S10 | 8.9×105 | S23 | 6.1×106 | NV10 | 3.6×104 | NV23 | 8.8×104 | |

| S11 | 5.2×106 | S24 | 4.9×107 | NV11 | 5.9×105 | NV24 | 1.3×104 | |

| S12 | 9.8×105 | S25 | 9.9×103 | NV12 | 3.8×103 | NV25 | 8.2×102 | |

| S13 | 5.9×103 | NV13 | 3.5×102 | |||||

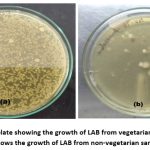

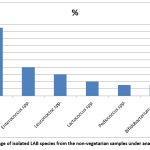

All the isolates in our study were identified as Gram-positive (Figure 2) and tested negative for both catalase and oxidase, indicating their classification within the Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) group. Considering the morphological characteristics, texture, and colour of the colony, along with physiological and biochemical assessments such as fermentation of sugar and production of gas, many bacterial species were isolated including Lactobacillus species, Lactococcus species, Leuconostoc species, Bifidobacterium species, Enterococcus species, Pediococcus species according to the Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. It is found that Lactobacillus species were isolated in the highest percentage (35%) from the vegetarian stool samples processed under anaerobic conditions followed by Lactococcus species (24%), Bifidobacterium spp (20%), Enterococcus spp (9%), Pediococcus spp (7%) and Leuconostoc spp (5%), respectively (Figure 3). The species isolated from the non-vegetarian stool samples were Lactobacillus spp. (44%), Enterococcus spp. (18%), Leuconostoc spp. (15%), Lactococcus spp. (9%), Pediococcus spp. (7%) and the Bifidobacterium spp. (7%) (Figure 4).

|

Figure 2: Gram’s staining observation under 10 x 100 magnifications using binocular LED research microscope (A- Lactobacillus acidophilus, B- Lactobacillus plantarum , C- Lactobacillus fermentum, |

|

Figure 3: Percentage of isolated LAB species from the vegetarian samples under anaerobic conditions. |

|

Figure 4: Percentage of isolated LAB species from the non-vegetarian samples under anaerobic conditions. |

All isolates identified as LAB via biochemical tests underwent additional screening to assess their probiotic efficacy. Initially, the development of isolates was assessed at lower pH levels. Among the 120 isolates examined, 82 exhibited positive growth at pH 3, with 54 of these bacterial isolates originating from the vegetarian samples and the remaining from the non-vegetarian samples. The growth of these isolates was subsequently analysed across various temperature conditions. Out of 82 isolates, 69 demonstrated robust growth at temp. 40°C and also at temp. 25°C. The isolates underwent additional screening to assess their tolerance to bile salts and their ability to withstand pancreatin exposure. Among the 69 isolates examined, 28 demonstrated significant tolerance to the concentrations of 0.3% (w/v) bile salts and 0.5% pancreatin. Out of the 28 isolates, 18 were obtained from the vegetarian sample, while 10 were derived from the non-vegetarian samples. Based on antibiotic resistance and antimicrobial activity against prevalent human pathogens, only five demonstrated the most favourable outcomes. The pathogenic micro-organisms used for detecting the antagonistic activity were Escherichia coli ATCC25922, Salmonella typhi MTCC733, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC25923, Shigella dysenteriae ATCC 13313, Klebsiella pneumoniae MTCC3384, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC27853. The clinical and laboratory standards institute’s criteria for determining the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) were followed in order to assess antibiotic susceptibility. The CLSI breakpoints were used to interpret the data.23,24

Discussion

This study sought to assess how vegetarian and non-vegetarian diets affect the prevalence and characteristics of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) in human faecal samples. The results demonstrate a greater prevalence and diversity of LAB among individuals following a vegetarian diet in contrast to those on a non-vegetarian diet. A total of 75 LAB isolates were sourced from vegetarian samples, while 45 were derived from non-vegetarian samples. This difference indicates that diets rich in plant-based foods could enhance the proliferation of LAB within the gut microbiota. This observation is consistent with earlier findings that indicate plant-based diets improve microbial diversity and stability in the gut.25 The colony-forming units CFU/mL varied between 10² and 10⁸, with vegetarian samples showing elevated LAB counts. This reinforces the idea that dietary habits play a pivotal role in shaping the composition of microbiota of gut.26

Morphological, physiological, and biochemical analysis identified several genera of LAB, including Leuconostoc, Lactococcus, Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, Enterococcus, and Pediococcus. In vegetarian samples, Lactobacillus species were predominant (35%), followed by Lactococcus (24%), Bifidobacterium (20%), Enterococcus (9%), Pediococcus (7%), and Leuconostoc (5%). Conversely, non-vegetarian samples showed a higher proportion of Lactobacillus (44%), Leuconostoc (15%) and Enterococcus (18%), with lower percentage of Lactococcus (9%) and Bifidobacterium (7%) while Pediococcus (7%) showed no difference. Interesting, the higher percentage of bifidobacteria from vegetarian samples suggest that the vegetarians are less susceptible to dipression and harbour higher percentage of happy bacteria than non-vegetarians. Bifidobacteria are known toproduce short chain fatty acids, particularle butyric acid which cause happiness. The prevalence of Lactobacillus species in both dietary groups aligns with current literature emphasising their common presence in the human gut.27 The heightened occurrence of Enterococcus species in non-vegetarian samples could be linked to dietary elements that promote their proliferation. The evaluation of probiotic potential showed that 82 out of 120 isolates demonstrated growth at pH 3, highlighting their acid tolerance. Of these, 69 strains exhibited strong growth at both at 25°C and 40°C, indicating their adaptability to different temperature conditions. Subsequent screening revealed 28 isolates exhibiting notable tolerance to 0.3% bile salts and 0.5% pancreatin, which are critical characteristics for endurance in the gastrointestinal environment. The results align with previous studies that have identified LAB strains exhibiting probiotic characteristics, such as tolerance to acid and bile.28 The increased quantity of probiotic derived from vegetarian samples (18 out of 28) may indicate the impact of plant-based diets on enhancing LAB with beneficial probiotic characteristics.29

Five isolates demonstrated significant antimicrobial activity against prevalent human pathogens, such as E. coli, S. aureus, K. pneumoniae, S. typhi, S. dysenteriae, and P. aeruginosa. This antagonistic effect highlights the promise of these LAB strains as probiotic candidates that can improve gut health by suppressing pathogenic bacteria. Comparable antimicrobial characteristics have been documented in LAB strains obtained from diverse sources, reinforcing their potential use in enhancing human health.30 Plant based diets contain a variety of carbohydrates that provide direct energy and facilitate sugar fermentation and the production of either lactic acid alone (homofermentation) or lactic acid with acetic acid (heterofermentation) that provide a suitable environment for the growth and development of diversity of LAB. Animal proteins, though, are good sources of proteins but have raised serious environmental issues like emission of greenhouse gases during meat production and red meat increases the health risks including various chronic diseases31. The digestibility of animal proteins is also poor in comparison to plant-based protiens that contain a large variety of amino acids in the form of oligopeptides that provide a wide range of nutrients to the growing LAB in the gut. Replacement of animal meat proteins by plant-based proteins maintains a nutritional balance that facilitates greater and higher diversity of LAB in the gut32.

Conclusion

This investigation emphasises the influence of dietary practices on the makeup and probiotic capabilities of gut microbiota. A vegetarian diet seems to promote a greater prevalence and diversity of LAB that exhibits beneficial probiotic characteristics. The identified LAB strains, especially those exhibiting antimicrobial properties, show potential for development as probiotic supplements aimed at enhancing gastrointestinal health. Plant-based diet is good for healthy gut microbiome. Vegetarian diet supports higher quantity and greater diversity of gut microbiome including the higher population of bifidobacteria that are commonly known as happy bacteria.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to Professor Jayanand, Pro Vice Chancellor, Shobhit Institute of Engineering & Technology, Deemed to-be-University, Meerut for constant encouragement and help in various ways.

Funding Sources

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

This statement does not apply to this article.

Ethics Statement

This research did not involve human participants, animal subjects, or any material that requires ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not involve human participants, and therefore, informed consent was not required.

Clinical Trial Registration

This research does not involve any clinical trials.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

Not Applicable

Author’s Contribution:

Anchal Bamal: Collected and analysed the samples,

Amar Prakash Garg: Helped in the identification of samples and their analysis and interpretation.

The paper is drafted by both the authors collectively.

References

- Hemarajata P, Versalovic J. Effects of probiotics on gut microbiota: mechanisms of intestinal immunomodulation and neuromodulation. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2013;6(1):39-51. doi:10.1177/1756283X12459294.

CrossRef - Kandler O., Weiss N. Genus Lactobacillus Beijerinck 1901, 212AL. In: Sneath, P.H.A., Mair, N.S., Sharpe, M.E., Holt, J.G. (Eds.), Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. Williams & Wilkins Co., Baltimore, 1986;1209-1234.

- Stiles ME, Holzapfel WH. Lactic acid bacteria of foods and their current taxonomy. Int J Food Microbiol. 1997;36(1):1-29. doi:10.1016/s0168-1605(96)01233-0.

CrossRef - Zhang YJ, Li S, Gan RY, Zhou T, Xu DP, Li HB. Impacts of gut bacteria on human health and diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(4):7493-7519. doi:10.3390/ijms16047493.

CrossRef - Granato D, Branco GF, Nazzaro F, Cruz AG, and Faria JAF. Functional Foods and Nondairy Probiotic Food Development: Trends, Concepts, and Products. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2010;9(3):292-302. doi:10.1111/j.1541-4337.2010.00110.x.

CrossRef - Shah, N. P. Functional cultures and health benefits. Dairy J. 2007;17:1262–1277. doi:10.1016/j.idairyj.2007.01.014.

CrossRef - Dunne C, Murphy L, Flynn S, et al. Probiotics: from myth to reality. Demonstration of functionality in animal models of disease and in human clinical trials. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1999;76(1-4):279-292.

CrossRef - Bisht N., and Garg A. P. Role of gut microbiota in human health. J. Biotech. 2021;16(1): 202-212.

- Glick-Bauer M, and Yeh M-C. The Health Advantage of a Vegan Diet: Exploring the Gut Microbiota Connection. 2014;6(11):4822-4838. doi:10.3390/nu6114822.

CrossRef - Derrien M and Veiga P. Rethinking Diet to Aid Human-Microbe Symbiosis. Trends Microbiol. 2017;25(2):100-112. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2016.09.011.

CrossRef - Wong M-W, Yi C-H, Liu T-T, et al. Impact of vegan diets on gut microbiota: An update on the clinical implications. Tzu-Chi Med J. 2018;30(4):200-203. doi:10.4103/tcmj.tcmj_21_18.

CrossRef - Astó E, Méndez I, Audivert S, Farran-Codina A, Espadaler J. The Efficacy of Probiotics, Prebiotic Inulin-Type Fructans, and Synbiotics in Human Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. 2019;11(2):293. doi:10.3390/nu11020293.

CrossRef - Kumar AR, Singh J, and Garg AP. Isolation, Characterization and Evaluation of Probiotic Potential of Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Human Colostrum. Biotech. Res. Comm. 2020;13(1):296-306. doi:10.21786/bbrc/13.1/48.

CrossRef - Hammes PH, Hertel C, Vos PD, et al. Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Springer, New York, 2009;3:456-479.

- Siddique S.P., Garg A. P. Isolation, characterization and quantitative enumeration of Lactic acid bacteria from human faeces. Biotech. Res. Comm. 2022;15:1. doi:10.21786/bbrc/15.1.33.

CrossRef - Bisht N., and Garg A.P. Isolation, characterization and probiotics value of Lactic acid bacteria from Milk and milk products. Biotech Today. 2019;9(2):54-63. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.21786/bbrc/ 14.1/28.

CrossRef - Tankoano A, Diop BM, Lingani SH, et al. Isolation and Characterization of Lactic Acid Bacteria producing Bacteriocin like inhibitory substance (BLIS) from “Gappal”, a dairy product from Burkina Faso. Microbi. 2019;9:343-358. doi:10.4236/aim.2019.94020.

CrossRef - Padmavathi T, Bhargavi R, Priyanka PR, Niranjan NR, Pavitra PV. Screening of potential probiotic lactic acid bacteria and production of amylase and its partial purification. J Genet Eng Biotechnol. 2018;16(2):357-362. doi:10.1016/j.jgeb.2018.03.005.

CrossRef - Leska A, Nowak A, Szulc J, Motyl I and Czarnecka-Chrebelska KH. Antagonistic activity of potentially Probiotic Lactic Acid Bacteria against Honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) Pathogens. 2022;11(11):1367. doi:10.3390/pathogens11111367.

CrossRef - Arya R. K., Singh J. and Garg A. P. In vitro evaluation of probiotic potentials of Lactic acid bacteria isolated from human colostrum. Biores. 2020;11(4):93-99. doi: 10.15515/abr.0976-4585.11.4.9399.

- Bin Masalam MS, Bahieldin A, Alharbi MG, et al. Isolation, Molecular Characterization and Probiotic Potential of Lactic Acid Bacteria in Saudi Raw and Fermented Milk. Evidence Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine (ECAM). 2018;2018:7970463. doi:10.1155/2018/7970463.

CrossRef - Khushboo, Karnwal A, Malik T. Characterization and selection of probiotic lactic acid bacteria from different dietary sources for development of functional foods. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1170725. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2023.1170725

CrossRef - CLSI Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically; Approved Standard—Tenth Edition. CLSI document M07-A10. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2015.

- CLSI Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 27th ed. CLSI supplement M100. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2017.

- Tomova A, Bukovsky I, Rembert E, et al. The Effects of Vegetarian and Vegan Diets on Gut Microbiota. Front Nutr. 2019;6:47. doi:10.3389/fnut.2019.00047.

CrossRef - Singh RK, Chang HW, Yan D, et al. Influence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human health. J Transl Med. 2017;15(1):73. doi:10.1186/s12967-017-1175-y.

CrossRef - Kiliç GB and Karahan AG. Identification of lactic acid bacteria isolated from the fecal samples of healthy humans and patients with dyspepsia, and determination of their ph, bile, and antibiotic tolerance properties. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;18(4):220-229. doi:10.1159/000319597

CrossRef - Wu H, Shum TF, and Chiou J. Characterization of the Probiotic Potential of Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Kimchi, Yogurt, and Baby Feces in Hong Kong and Their Performance in Soymilk Fermentation. Microorganisms. 2021;9(12):2544. doi:10.3390/microorganisms9122544.

CrossRef - Chen Z, Leng X, Zhou F, et al. Screening and Identification of Probiotic Lactobacilli from the Infant Gut Microbiota to Alleviate Lead Toxicity. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. 2023;15(4):821-831. doi:10.1007/s12602-021-09895-0.

CrossRef - Li B, Pan LL, and Sun J. Novel Probiotic Lactic Acid Bacteria were Identified from Healthy Infant Feces and Exhibited Anti-Inflammatory Capacities. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022;11(7):1246. doi:10.3390/antiox11071246.

CrossRef - Chaudhary V, Garg AP, and Kumar U. Physical, Nutritional, Textural and Sensory Properties of Wheat Bread Supplemented With Soybean: Finger Millet and Flax Seeds Flour”. European Journal of Nutrition & Food Safety.2024;16(5):80-92. https://doi.org/10.9734/ejnfs/2024/v16i51424.

CrossRef - Bisht N, Garg AP. Health management using probiotics. J Adv Pediatr Child Health. 2023;6:001-006. DOI: 10.29328/journal.japch.1001053

CrossRef

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.