Manuscript accepted on : 22-05-2025

Published online on: 10-06-2025

Plagiarism Check: Yes

Reviewed by: Dr. Kranthi Kumar

Second Review by: Dr. Ramdas Bhat

Final Approval by: Dr. Wagih Ghannam

Niranjana Edakannoth Sasidharan* , Kowski Shebina Dhas Christu Dhas Arul Sornabai

, Kowski Shebina Dhas Christu Dhas Arul Sornabai , Mohammed Umar Ali Niyamath Ali

, Mohammed Umar Ali Niyamath Ali , Nikitaa Rangasamy Vijayaragavan

, Nikitaa Rangasamy Vijayaragavan , Nithishkumar Amritharaj

, Nithishkumar Amritharaj , Bergin Vijayakumar Thankam

, Bergin Vijayakumar Thankam , Kannan Subramaniam

, Kannan Subramaniam and Ananadhasayanam Aravamuthan

and Ananadhasayanam Aravamuthan

Department of Pharmacy practice, SSM College of Pharmacy, Erode, Tamil Nadu, India.

Corresponding Author E mail: niranjanaes@gmail.com

DOI : http://dx.doi.org/10.13005/bbra/3403

ABSTRACT: Anticoagulant therapy is a cornerstone in the management of various cardiovascular and neurological disorders as it can impose high risk of thromboembolic events. Time in Therapeutic Range (TTR) is a key indicator of anticoagulant therapy by measuring how often a patient’s INR remains within the target range to ensure the safe use of oral anticoagulant therapy.The cohort study involved 110 outpatients in the department of cardiology (n=80) and neurology (n=30) who were on oral anticoagulant treatment (WARFARIN/ACENOCOUMAROL) for not <6 months. Rosendaal’s linear interpolation method was used to calculate TTR with TTR ≥ 60% indicating good control and TTR < 60% as poor control. The data on clinical events such as alopecia, gum bleeding, and allergic reactions and factors influencing TTR were collected through patient interactions and medical records.In cardiology, 57.5% of patients had TTR<60% and had a higher incidence of adverse clinical effects when compared to neurology patients where the distribution was more balanced and clinical events were less frequent. Average monthly doses were 7±2.31 mg of Warfarin and 2.5±1.45 mg of Acenocoumarol in cardiology, and 1.98±0.62 mg of Acenocoumarol in neurology. The findings reveal that while body weight shows a significant association with TTR (p<0.002), other variables such as age, gender, and co morbidities did not exhibit strong statistical correlations. Importantly, there was no significant link between TTR and the occurrence of adverse effects, suggesting that factors beyond TTR may play a critical role in clinical outcomes.

KEYWORDS: Anticoagulants; Acenocoumarol; Cardiology; Neurology; Rosendaal’s Method; Warfarin

Download this article as:| Copy the following to cite this article: Sasidharan N. E, Sornabai K. S. D. C. D. A, Ali M. U. A. N, Vijayaragavan N. R, Amritharaj N, Thankam B. V, Subramaniam K, Aravamuthan A. Estimating Time in Therapeutic Range in Cardiology and Neurology Patients on Warfarin/Acenocoumarol: Assessing its Association with Clinical Outcomes and Influencing Factors for it’s Reliable Use in General Practice. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(2). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Sasidharan N. E, Sornabai K. S. D. C. D. A, Ali M. U. A. N, Vijayaragavan N. R, Amritharaj N, Thankam B. V, Subramaniam K, Aravamuthan A. Estimating Time in Therapeutic Range in Cardiology and Neurology Patients on Warfarin/Acenocoumarol: Assessing its Association with Clinical Outcomes and Influencing Factors for it’s Reliable Use in General Practice. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(2). Available from: https://bit.ly/3SKdbWQ |

Introduction

Anticoagulant therapy is a cornerstone in the management of various cardiovascular diseases and neurological disorders, including atrial fibrillation, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and stroke prevention. These medications have well-proven effectiveness for those indications but pose significant challenges including increased bleeding risk due to the narrow therapeutic window and the high variability in patient response.1 According to several studies, anticoagulants, particularly in ambulatory care, were accountable for 12% of adverse reactions because of their risk of bleeding. Keeping patients within their therapeutic range, which is commonly expressed as time in therapeutic range (TTR), will help to enhance the efficacy of anticoagulant medication.TTR is a critical parameter indicating the proportion of time a patient’s International Normalized Ratio (INR) is within the target range, reflecting effective anticoagulation and minimizing the risk of adverse events and it is important to determine the current standard of anticoagulation care and establish new objectives. It has been found that TTR can strongly predict both bleeding and thromboembolic events.2A greater TTR can improve anticoagulation therapy whereas suboptimal TTR is associated with increased risks of thromboembolic events when INR is too low and hemorrhagic complications when INR is too high.Using these integrated statistics, TTR shows the days with INRs between 2.0 and 3.0 over the total number of days.2Therefore, regular monitoring and appropriate dose adjustments are essential to maintain therapeutic efficacy and safety.The most used method to calculate TTR is the Rosendaal linear interpolation method.3-4 The value is calculated from the number of days within target range divided by the total number of days in the observation period. The cardiology and neurology departments are at the forefront of managing patients requiring anticoagulant therapy due to the high prevalence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular conditions in these specialties.5 A thorough evaluation of TTR and safety audits in these settings can provide valuable insights into current practices, identify areas for improvement, and enhance patient outcomes. The current study aims to evaluate the TTR and conduct a safety audit of anticoagulant therapy in patients attending the cardiology and neurology departments. By analyzing TTR, adverse drug reactions (ADRs), and adherence to clinical guidelines, this research seeks to optimize anticoagulant management, lessen the incidence of complications, and enhance the standard of care for patients on anticoagulant therapy.

Materials and Methods

The cohort study was carried out in the outpatient department of cardiology and neurology department of a tertiary care hospital, Erode, Tamil Nadu for a period of 6 months with approval from hospital ethical committee. Patients greater than 18 years of age with VKA or OAC therapy had at least three INR values not more than 9 weeks apart with informed consent were recruited in the study whereas patients with a history of any blood related disorders were excluded. All the data were collected by direct interaction with patients and from patient medical records after getting approval from the hospital ethical committee. (Reg.No: ECR/948/Inst/TN/2018/RR-22)

International Normalized Ratio

The target range for INR in our hospital is 2 to 3. INR < 2 is defined as subtherapeutic range while INR > 3 as supratherapeutic range. The study designed maximum monitoring interval of 4 weeks both for cardiology and neurology patients.

Time in Therapeutic Range

The time in therapeutic range (TTR) is calculated by dividing the total number of person-days on anticoagulant medication by the number of person-days that fall within a predefined therapeutic range. TTR was determined using the Rosendaal linear interpolation approach,4-6 which assigns a particular INR value to each patient on each day and assumes a linear relationship between two INR values. The patients were categorized into two groups based on their TTR interpretation.

Statistical Analysis

The data obtained was entered into Microsoft office Excel and analyzed using SPSS. Logistic regression analysis was used to estimate the probability of events happening.

Results

The current study recruited 110 outpatients in the cardiology and neurology department of tertiary care hospital, (cardiology = 80; neurology =30) who were on oral anticoagulant therapy for a period of less than 6 months.

|

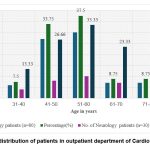

Figure 1: Age wise distribution of patients in outpatient department of Cardiology and Neurology. |

|

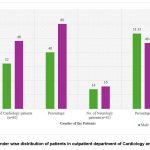

Figure 2: Gender wise distribution of patients in outpatient department of Cardiology and Neurology |

Figure 1 & 2 showed that, most of the patients recruited in the study were females (60% in cardiology and 53.33% in neurology patients) with the age group of 51-60 years (37.5% of cardiac patients and 33.33% of neurologic patients) followed by 41-50 years (33.75% of cardiology patients and 26.66 % of neurologic patients), 61-70 years (8.75% of cardiac and 23.33% of neurologic patients) and 71 -80 years for only cardiac patients (8.75%).

|

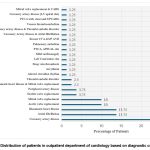

Figure 3: Distribution of patients in outpatient department of cardiology based on diagnostic conditions |

|

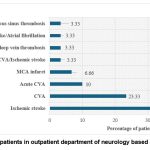

Figure 4: Distribution of patients in outpatient department of neurology based on diagnostic conditions |

Coronary artery disease (CAD) (22.5%), atrial fibrillation (AF) (13.75%), rheumatic heart disease (13.75%), other thromboembolic disorders (pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, venous thromboembolism etc.) (13.75%), Aortic valve replacement (7.5%) and Double valve replacement (3.75%) were the common diagnostic conditions identified in patients visited cardiology department. In neurological patients, cerebrovascular accident (43.33%) was more common. (Figure 3& 4).

Table 1: Pattern of Anticoagulation treatment among cardiology and neurology patients

| S. No | Treatment | Cardiology Patients (n=80) | Neurology Patients (n=30) | ||

| Average monthly dose(In mg) | Percentage (%) | Average monthly dose(In mg) | Percentage(%) | ||

| 1 | T.Warfarin | 7±2.31 | 6.25 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | T.Acenocoumarol | 2.50±1.45 | 93.75 | 1.98±0.62 | 100 |

Table 1 depicts the pattern of anticoagulant treatment among the two study groups. The majority of patients (93.75%) with cardiovascular conditions were treated with Tab. Acenocoumarol at an average dose of 2.50±1.45 mg per month (± SD), while 6.25% of patients were treated with Tab. Warfarin at an average dose of 7±2.31 (± SD) as therse are the mainstay treatment for thromboembolic conditions. In neurology, patients were solely given Tab. Acenocoumarol, which is a primary drug for cerebral embolism, with an average monthly dose of 1.98±0.62.

|

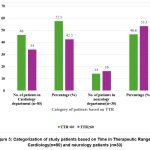

Figure 5: Categorization of study patients based on Time in Therapeutic Range in Cardiology(n=80) and neurology patients (n=30). |

Figure 5 categorized the patients (both cardiology and neurology) based on their Time in Therapeutic Range (TTR) which calculated by Rosendaal method into two groups as good control group (TTR≥60%) and poor control group (TTR< 60%). In cardiology department, 46 (57.5%) patients had a TTR of less than 60%, indicating that most patients struggled to maintain their anticoagulation within the therapeutic range. Conversely, 34 (42.5%) patients achieved a TTR ≥60%, reflecting better management of anticoagulation therapy in this group. In neurology department, the distribution was more balanced, with 14 patients (46.6%) having a TTR of less than 60% and 16 patients (53.3%) achieving a TTR above 60%.

Table 2: Characteristics of Anticoagulation therapy among study patients in Cardiology and Neurology department.

| Characteristics | Cardiology Patients (n=80) | Neurology Patients (n=30) | ||

| TTR<60% | TTR ≥60% | TTR <60% | TTR ≥60% | |

| Average INR | 2.186±0.65 | 2.5±0.33 | 1.69±0.39 | 2.36±0.23 |

| Average time between INR checks (In Days) | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

In patients with cardiac conditions, of 240 INR values collected, patients with a TTR of less than 60% had an average INR of 2.186 ± 0.65, while those with a TTR greater than or equal to 60% had a higher average INR of 2.5 ± 0.33. In the neurology department, patients with a TTR of less than 60% had an average INR of 1.69 ± 0.30, whereas those with a TTR greater than 60% had an average INR of 2.36 ± 0.23. Similarly, the average interval between INR checks was 60 days for both groups. (Table 2)

Table 3: Clinical events occurred in study patients receiving Anticoagulation treatment in Cardiology and Neurology department.

| S. No | Adverse clinical Effects | Cardiology Patients (n=80) | Neurology Patients (n=30) | ||||

| TTR <60%(n=46) | TTR ≥60%(n=34) | Odds ratio (P value) (Logistic regression | TTR <60%(n=14) | TTR ≥60%(n=16) | Odds ratio (P value) (Logistic regression) | ||

| 1 | Alopecia | 3 | 2 | 0.893(0.904) | 3 | 1 | 0.200 (0.221) |

| 2 | Gum bleeding | 6 | 4 | 0.373(0.641) | 2 | 1 | 0.073 (0.090) |

| 3 | Allergic reactions (rashes &Itching) | 7 | 2 | 0.360(0.224) | 3 | 1 | 0.021 (0.215) |

P value <0.05 is considered as significant

Table 3 depicts that, in cardiology patients, 15.04% of patients in category of TTR<60% experienced allergic reactions (rashes, itching) followed by gum bleeding (7.5%) and alopecia (6.5%). In contrast, among those with a TTR ≥60%, 4 patients had gum bleeding, 2 had alopecia and 2 reported allergic reactions. These findings suggest that patients with poorer TTR may be more susceptible to these adverse events, especially gum bleeding in cardiology patients highlighting the need for improved anticoagulation management. The statistical analysis showed that, the TTR does not predict the likelihood of alopecia (OR 0.893, p value>0.05), gum bleeding (OR 0.373, p value>0.05) and allergic reactions (OR 0.360, p value>0.05) In the neurology department, patients with a TTR of less than 60% had 3 cases of alopecia, 2 cases of gum bleeding, and 3 cases of allergic reactions. Those with a TTR ≥60% there was 1 reported case of alopecia and gum bleeding and 1 case of an allergic reaction. This indicates a lower frequency of adverse events in patients with better TTR, but overall, the incidence of these events was lower in the neurology department compared to cardiology. The statistical analysis showed that TTR does not have a statistically significant association on the likelihood of these clinical events as indicated by p values>0.05. Although the odds ratios (Alopecia OR 0.200 (p value 0.221), gum bleed OR 0.073 (p value 0.090) and allergic reactions 0.021 (p value 0.215) suggested a reduced likelihood of these events with TTR≥60%.

Table 4: Factors influencing Time in Therapeutic range among study cardiac patients (n=80)

| S. No | Factors | Cardiology Patients(n=80) | ||||

| TTR <60%(n=46) | TTR≥ 60%(n=34) | P value

|

Odds ratio | |||

| 1 | Age | 54±12.65 | 52.15±10.3 | 0.103 | 0.954 | |

| 2 | Gender | M | 20 | 12 | 0.555 | 1.491 |

| F | 26 | 22 | ||||

| 3 | Comorbidities | 30 | 29 | 0.067 | 2.988 | |

| 4 | Smoking habits | 6 | 2 | 0.075 | 1.780 | |

| 5 | Alcoholism | 4 | 2 | |||

| 6 | Smoking &Alcohol | 4 | 1 | |||

| 7 | Underweight | 1 | 0 | <0.002 | 0.224 | |

| Normal | 14 | 25 | ||||

| Overweight | 21 | 8 | ||||

| Obese | 10 | 1 | ||||

| 8 | Polypharmacy | 20 | 20 | 0.618 | 1.354 | |

P value <0.05 is considered as significant

Table 4 showed that, in cardiology patients in both the groups(TTR<60%; TTR≥60%) there was no significant difference in the average age (54 ± 12.65 in TTR<60%; 52.15 ± 10.3 years in TTR≥60%) (OR 0.954, p value 0.103), female patients were high in number 26 (56.5%) in TTR<60% and 22 (35.2%) in TTR≥60% (OR 1.491, p value 0.555). The presence of comorbid conditions was comparatively high among patients with TTR<60% (65.2%) but showed as statistically non-significant (OR 2.988, p value 0.067). Smoking and alcoholism were found to be a major sedentary lifestyle habit among the study patients.In patients with TTR<60%, 30.43% of patients exhibited the habits of smoking and alcoholism and 14.7% in patients with TTR≥60%. The statistical analysis showed that the lower rates of these risk factors may contribute to better TTR but found to be less significant as p value>0.05 (OR 1.780, p value 0.075). There was a significant difference in BMI categories between the groups, with the TTR <60% group having a higher percentage of underweight and obese patients (, p value< 0.002). Both study groups had similar rates of polypharmacy (20 patients in each group), with no significant impact on TTR (p = 0.618). (Table 4)

Table 5: Factors influencing Time in Therapeutic range among neurologic patients (n=30)

| S. No | Factors | Neurology Patients (n=30) | ||||

| TTR <60%)(n=14) | TTR≥ 60%(n=16) | P value | Odds ratio | |||

| 1 | Age | 50.85±8.96 | 50.85±8.96 | 0.562 | 1.021 | |

| 2 | Gender | M | 8 | 6 | 0.962 | 0.946 |

| F | 6 | 10 | ||||

| 3 | Comorbidities | 10 | 8 | 0.166 | 0.274 | |

| 4 | Smoking habits | 3 | 1 | 0.700 | 1.163 | |

| 5 | Alcoholism | 0 | 3 | |||

| 6 | Smoking &Alcohol | 3 | 0 | |||

| 7 | Underweight | 0 | 0 | 0.420 | 0.555 | |

| Normal | 7 | 11 | ||||

| Overweight | 6 | 4 | ||||

| Obese | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 8 | Polypharmacy | 5 | 7 | 0.520 | 1.828 | |

P value <0.05 is considered as significant

In neurology patients, the average age was same for both TTR <60% and TTR ≥60% groups (50.85 ± 8.96), with no significant difference (p value = 0.562). It was also noted that male to female ratio was also similar. In patients with TTR <60%, 8 were males and 6 were females, while in the TTR ≥60% group, 6 were males and 10 were. The difference in gender distribution was not statistically significant (OR 0.946, p value 0.962). About 10 patients had comorbidities in TTR <60% group whereas 8 had in TTR ≥60% group which was not statistically significant (p value = 0.166).Smoking was high in patients with TTR <60% (3 patients) compared to the TTR ≥60% group (1 patient), but this was also not statistically significant (p value = 0.700). Alcoholism was reported by 3 patients in the TTR ≥60% group, while no patients in the TTR <60% group had a history of alcoholism. The distribution of BMI was the same in the study groups. In the TTR <60% group, 7 were normal weight, 6 overweight, and 1 obese. In the TTR ≥60% group, 11 were normal weight, 4 overweight, and 1 obese. The difference was not statistically significant (p value= 0.420). Polypharmacy was observed in 5 patients with TTR <60% group and 7 with TTR ≥60% group and this difference was not statistically significant (p value= 0.520). (Table 5)

Discussion

The evaluation of TTR (time in therapeutic range) and safety audit of anticoagulant prescriptions are significant in ensuring optimal patient outcomes in cardiac and neurology departments where the risk of thromboembolic events is high. The study findings given in figures 1 & 2 indicated that older female adult patients were mainly experiencing cardiovascular and neurological conditions, which indicated age and gender can act as major risk factors in disease progression. Another research conducted by Sevda Turen et al., involved 518 patients with an average age of 57.6±12.3 years, of whom 54.4% were female, which are similar to our study findings.7 Coronary artery disease (22.5%), atrial fibrillation (13.75%), and rheumatic heart Disease (13.75%) were the most common diagnoses among cardiology patients, serving as primary indications for anticoagulant therapy. Similarly, Majerczyk et al., reported that atrial fibrillation, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism⁸ were the leading indications of anticoagulation therapy. In neurology patients, cerebrovascular accident (43.33%) was more common. (Figures 3 & 4).

Table 1 depicted the pattern of anticoagulant treatment among the two study groups. In patients with cardiovascular conditions, 93.75% were treated with Tab. Acenocoumarol [average dose of 2.50±1.45 mg per month (± SD)] whereas 6.25 % of patients were treated with Tab. Warfarin [average dose of 7±2.31 (± SD)]. In neurology patients were only treated with Tab. Acenocoumarol [average monthly dose of 1.98±0.62], which is a drug of choice for cerebral embolism. The variety of conditions treated with oral anticoagulants showed how complex patient care is and denoted that the anticoagulation treatment needs to be tailored to everyone, as these patients are at high risk and need careful management to prevent further complications. In another study conducted by Dalmau Llorca MR et al., 41,430 patients were evaluated, with 93% receiving acenocoumarol and 7% treated with warfarin, which indicated the common use of oral anticoagulants among the patients. 9 Top of FormBottom of Form

Time in Therapeutic Range (TTR) was calculated by the Rosendaal method, and the patients were categorised into two groups: the good control group (TTR≥60%) and the poor control group (TTR<60%). In the cardiology department, more than half of the patients struggled to maintain their anticoagulation within the therapeutic range. Whereas in the neurology department, the distribution was more balanced. (Figure 5) These findings suggested the need for individualised treatment strategies, close monitoring and patient education. This aligns with the findings of a study conducted by Xiliang Zhu et al., which stated that the time in therapeutic range (TTR) was calculated, and patients were classified into two groups: the Good Control group (TTR ≥ 60%) and the Poor Control group (TTR < 60%). Out of 274 patients, 153 were in the Good Control group, while 121 were in the Poor Control group.10 Table 2 shows that in cardiology, patients with TTR < 60% had a lower average INR (2.186 ± 0.65), indicating more variability in anticoagulation. In neurology, those with TTR < 60% had a significantly lower INR (1.69 ± 0.30) than patients with TTR ≥ 60% (2.36 ± 0.23), suggesting a higher risk of subtherapeutic anticoagulation. These findings emphasize the importance of maintaining a stable INR for better patient outcomes.

Table 3 showed that, in the cardiology department, patients with poorer TTR (< 60%) experienced a higher rate of adverse drug reactions. Among which gum bleeding was more common in the poor control group, which indicated the need for more effective anticoagulation management in this population. Contrast to this, those with TTR ≥ 60% had fewer adverse effects. However, these findings were not statistically significant as there is no correlation between TTR and the likelihood of events indicating the presence of other attributing factors to ADRs. In neurology department, the occurrence of adverse effects was lower in patients with TTR < 60% and very fewer reports in those with TTR ≥ 60. Despite the lower overall incidence of ADRs in neurology patients, statistical analysis again showed no significant association between TTR and these adverse events, with p value>0.05.

The current study also discussed the possible factors which can influence TTR among both cardiology and neurology patients. Age, gender, presence of co morbid conditions, lifestyle habits like smoking, alcoholism etc., BMI interpretations and polypharmacy were considered as the major influencing factors. The findings suggested that, among cardiology patients, age [(54 ± 12.65 in TTR<60%; 52.15 ±10.3 in TTR≥60%); (OR 0.954, p value 0.103)] may not be a significant factor affecting TTR in this cohort. The proportion of female patients was high in poor TTR control group (TTR<60%) but not statistically significant. In another study conducted by Xiliang Zhu et al., found that female gender is associated with TTR<60%.10 Comorbid conditions were comparatively high in the TTR <60% group indicating the least probability of influence on anticoagulation control (p value = 0.067). Smoking (30.43%) and alcoholism (14.7%) were more prevalent in the poor control group. However, the statistical analysis (p value = 0.075) showed a marginal statistical significance implying that these factors cannot be considered as the main determinants of TTR. In a study conducted by Derek Gateman et al., the lifestyle habits were suggested that current smoking might be associated with a TTR of less than 60% (OR = 4.71, 95% CI 0.97 to 22.93).11Additionally, a study by Dalmau Llorca MR et al., found that poor anticoagulation control was primarily linked to advanced alcoholism (OR = 1.38).8 There was a significant difference in BMI categories between the groups, with the TTR <60% group having a higher percentage of underweight and obese patients (p < 0.002). This suggested that BMI have an important role in anticoagulation control, with an increase in body weight potentially affecting drug metabolism or treatment adherence. Both study groups had similar rates of polypharmacy (20 patients in each group), with no significant impact on TTR (p = 0.618). This suggested that polypharmacy may not be a major influencing factor in this study population. In contrast to our findings another study by Bahram-Fariborz Farsad et al., found that taking more than four medications is associated with a poor TTR (TTR <60%).12(Table 4)

The study findings given in Table 5 indicated that the factors examined in this study—such as age, gender, comorbidities, smoking, alcoholism, BMI, and polypharmacy did not show statistically significant associations with TTR in neurology patients. Although it was also observed that the higher smoking rates in the poor control group, these differences were not substantial enough to be considered significant. This could indicate that while these factors may have some influence on anticoagulation control, their impact may be limited by other factors not fully captured in this study. Further research with larger sample sizes may provide clearer insights into the influences on anticoagulation management in this population.

Conclusion

The study emphasizesthe importance of monitoring and evaluation of Time in Therapeutic Range (TTR) and conducting safety audits of oral anticoagulant therapy particularly among cardiovascular and neurology patients who are at the risk of thromboembolic events. Similarly, the patients with TTR≥60% experienced fewer clinical events like alopecia, gum bleeding and allergic reactions though these outcomes were not statistically significant. The influencing factors such as age, gender, co morbid conditions, bodyweight, lifestyle habits like smoking and alcoholism and polypharmacy were examined for their influence on TTR control and bodyweight had a marginal influence in cardiovascular patients. While TTR did not significantly predict clinical events, these findings highlight the necessity for further research to better understand the factors affecting anticoagulation control and to improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgement

We gratefully acknowledge SSM College of Pharmacy, Erode, Tamil Nadu, and Sudha Institute of Medical Sciences, Erode, for providing the research facilities necessary for this study.We are also thankful to the staff at the cardiology and neurology departments of the tertiary care hospital for their assistance during the data collection phase, as well as to colleagues who offered valuable feedback throughout the research process.

Funding Sources

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

This statement does not apply to this article.

Ethics Statement

After submitting the proposal with study title, duration, inclusion and exclusion criteria, objectives and brief methodology of the work to be carried, Institutional Review Board of Sudha hospital has approved our study. Registration Number:ECR/948/Inst/TN/2018/RR-22 SH/IEC/Approval-34 February 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not involve human participants, and therefore, informed consent was not required.

Clinical Trial Registration

This research does not involve any clinical trials.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

Not Applicable

Author Contributions

Niranjana Edakannoth Sasidharan: Concept, designing Methodology, Overall Supervision, Manuscript correction

Kowski Shebina Dhas Christu Dhas Arul Sornabai: Data collection, Data Analysis, Review, Writing

Mohammed Umar Ali Niyamath Ali: Data collection, Data Analysis, Review, Writing – original draft

Nikitaa Rangasamy Vijayaragavan: Data collection, Data Analysis, Review, Writing – original draft

Nithishkumar Amritharaj: Data collection, Data Analysis, Review, Writing – original draft

Bergin Vijayakumar Thankam: Supervision, manuscript correction

Kannan Subramaniam: Critical Review, Intellectual guidance

Ananadhasayanam Aravamuthan: Critical Review, Intellectual guidance

References

- GregoryYH Lip, Marco Proietti, Tatjana Potpara, et al. Atrial fibrillation and stroke prevention: 25 years of research at EP Europace journal. Europace.2023;25(9):euad226.DOI: 1093/europace/euad226

CrossRef - Razouki Z, Ozonoff A, Zhao S, Jasuja GK, Rose AJ. Improving quality measurement for anticoagulation adding international normalized ratio variability to percent time in therapeutic range. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes.2014;7(5):664-669.DOI: 1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.114.000804

CrossRef - James AReiffel. Time in the Therapeutic Range for Patients Taking Warfarin in Clinical Trials: Useful, but Also Misleading, Misused, and Overinterpreted. Circ.2017; 35(16):1475-1457. DOI: 1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026854

CrossRef - ScheinJR, WhiteCM, NelsonWW, KlugerJ, Mearns ES, ColemanCI. Vitamin K antagonist use: evidence of the difficulty of achieving and maintaining target INR range and subsequent consequences. Thrombosis J. 2016;14(1):14.DOI: 1186/s12959-016-0088-y

CrossRef - Gregory YH Lip, Deirdre ALane, RadosławLenarczyk, et al. Integrated care for optimizing the management of stroke and associated heart disease: a position paper of the European Society of Cardiology Council on Stroke.Eur Heart J.2022;43(26): 2442–2460.OI: 1093/eurheartj/ehac245

CrossRef - Rosendaal FR, Cannegieter SC, Van der Meer FJ,BrietE.A method to determine the optimal intensity of oral anticoagulant therapy. Thromb Haemost.1993;69(3):236–239.PMID: 8470047

CrossRef - TurenS,Turen S. Determination of Factors Affecting Time in Therapeutic Range in Patients on Warfarin Therapy. Biol Res Nurs.2023;25(1):170-178.DOI: 1177/10998004221127977

CrossRef - MajerczykD,Rusche K,SakharkarP. Assessment of time in therapeutic range with warfarin therapy in pharmacist versus usual care group: a retrospective cohort study”. Asian J Pharm Clin Res.2020;13(7):68-71.DOI:22159/ajpcr.2020.v13i7.37699

CrossRef - Dalmau LlorcaMR, Aguilar Martin C, Carrasco-QuerolN, et al. Anticoagulation Control with Acenocoumarol or Warfarin in Non-Valvular Atrial Fibrillation in Primary Care (Fantas-TIC Study). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(11):5700.DOI: 3390/ijerph18115700

CrossRef - Zhu X, XiaoX, Wang S, Chen X, LuG, LiX.Rosendaal linear interpolation method appraising of time in therapeutic range in patients with 12-week follow-up interval after mechanical heart valve replacement. Front. Cardiovasc. Med.2022;9:1-7.DOI: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.925571

CrossRef - DerekGateman., Melissa ElizabethTrojnar., GinaAgarwa. Time in therapeutic range Warfarin anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation in a community-based practice.Can. Fam. Physician. 2017; 63(10):425-431.PMID: 29025819; PMCID: PMC5638490.

- Farsad B.F., AbbasinazariM., Dabagh A., Bakshandeh H. Evaluation of Time in Therapeutic Range (TTR) in Patients with Non-Valvular Atrial Fibrillation Receiving Treatment with Warfarin in Tehran, Iran: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(9):FC04-6.doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/ 21955 .8457

CrossRef

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.