Manuscript accepted on : 28-04-2025

Published online on: 27-05-2025

Plagiarism Check: Yes

Reviewed by: Dr. Vishal Patel

Second Review by: Dr. Supriya Mhamane

Final Approval by: Dr. Wagih Ghannam

Manoj Dhandapani and Dheepan George*

and Dheepan George*

Department of Microbiology, AVS College of arts and science (Autonomous), Salem, India.

Corresponding Author E-mail:dheepanmicro2021@gmail.com

DOI : http://dx.doi.org/10.13005/bbra/3405

ABSTRACT: Tryptanthrin, a naturally occurring indoloquinazoline alkaloid, exhibits remarkable anticancer potential. This study explores the isolation of Pseudomonas spp. from soil as a novel microbial source of tryptanthrin and its derivatives, followed by comprehensive in vitro and in silico analyses to evaluate their anticancer activity. Soil samples were collected and processed through serial dilution to isolate fluorescent Pseudomonas species, which were then identified using morphological, biochemical, and molecular (DNA extraction and sequencing) techniques. Tryptanthrin was extracted from the bacterial culture and further synthesized chemically to improve yield and structural diversity.Eight derivatives of tryptanthrin were identified through GC-MS and LC-MS analyses, with prior separation conducted via thin-layer chromatography (TLC). The anticancer potential of these compounds was investigated using molecular docking against key cancer-associated proteins, including topoisomerase II and EGFR. Protein and ligand structures were prepared and optimized for docking simulations, which revealed strong binding affinities and favorable interaction profiles, suggesting possible mechanisms of anticancer action.This integrated approach highlights the significance of microbial alkaloids, particularly from Pseudomonas spp., as a promising source of bioactive compounds. The findings support further preclinical development of tryptanthrin-based derivatives as novel anticancer therapeutics.

KEYWORDS: Antibacterial; Anti-Inflammatory; Anti-Cancer; Cell Proliferation; Fluorescent bacteria; Tryptanthrin

Download this article as:| Copy the following to cite this article: Dhandapani M, George D. In Vitro Study of Tryptanthrin and its Derivatives: A Potent Alkaloid Compound from Fluorescent Bacteria Pseudomonas sps in Anticancer Effects through Drug Design. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(2). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Dhandapani M, George D. In Vitro Study of Tryptanthrin and its Derivatives: A Potent Alkaloid Compound from Fluorescent Bacteria Pseudomonas sps in Anticancer Effects through Drug Design. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(2). Available from: https://bit.ly/3Z0CCqx |

Introduction

The Pseudomonas genus includes over 120 species of rod-shaped, Gram-negative, and flagellated bacteria commonly found in humid environments such as soil and water.1 Among them, Pseudomonas aeruginosa is particularly notable for its ability to infect humans, animals, and plants. Due to its significance as a human pathogen, extensive research has been conducted on its virulence factors and regulatory systems. Tryptanthrin is a potent alkaloid compound known for its diverse biological properties, including anti- inflammatory, antimicrobial, and anticancer activities.2 Fluorescent strains of Pseudomonas are recognized for producing a broad spectrum of bioactive compounds with promising therapeutic applications. In light of rising drug resistance and the limitations of conventional chemotherapeutics, the discovery of new anticancer agents has become increasingly critical. Natural products are especially valuable in this regard due to their structural complexity and varied pharmacological effects.

Tryptanthrin and its derivatives have drawn significant attention for their cytotoxic activity against various cancer cell lines.3-5 Originally isolated from plant sources, this compound is now also being explored in microbial systems, particularly Pseudomonas spp., due to their unique biosynthetic capabilities.6-8 By elucidating the biosynthetic pathways involved, researchers aim to fully exploit the therapeutic potential of tryptanthrin for cancer treatment9. A multidisciplinary approach integrating microbiology, chemistry, and pharmacology is essential for advancing our understanding of tryptanthrin’s mechanisms of action and for developing safer, more effective anticancer agents.10-13 With recent technological advancements and collaborative research, scientists are uncovering the molecular basis of its pharmacological effects, laying the groundwork for the discovery of novel drug candidates.

P. aeruginosa is highly adaptable and metabolically versatile, thriving in a wide range of environments, including soil, water, hospital settings, drains, swimming pools, river water, and even on vegetables. This environmental resilience further supports its potential as a sustainable source for valuable bioactive compounds.14-17

Materials and Methods

Isolation of Pseudomonas speciesfrom soil

Soil Sample Collection

Start by collecting fresh soil from a moist, nutrient-rich area, preferably around the roots of healthy plants (called the rhizosphere), as this region often harbours microbial communities including Pseudomonas. Use a clean spoon or spatula to collect about 10 grams of soil from a depth of 5–10 cm, and place it in a sterile container or zip-lock bag. Label the sample (10 December 2024, l, Latitude: 11.0892995 Longitude:77.9731565, 3XQF+Q63 Thengaperumalpalayam,vengarai post,Paramathivelurtaluk,Namakkaldistrict, Tamil Nadu and SLC_20241210_001)

Preparation of soil suspension

To extract bacteria from the soil, take 1 gramof the collected soil and add it to 9 milliliters(0.009 liters) of sterile distilled water in a test tube or conical flask. Shake or vortex the mixture vigorously for 300–600 seconds (5–10 minutes)to dislodge the microbes from soil particles. This creates the primary soil suspension.Next, perform serial dilutions by transferring 1 milliliter (0.001 liters) of this suspension into 9 milliliters (0.009 liters)of fresh sterile water, repeating this process to achieve dilutions from 10⁻¹ to 10⁻⁵. Serial dilution reduces the number of bacteria, making it easier to isolate single colonies.

Inoculation on Selective Media

Using a sterile pipette, transfer 0.1 milliliters (1 × 10⁻⁴ liters) from each diluted tube onto King’s B agar plates or Cetrimide agar, both of which are selective for Pseudomonas species. Spread the inoculum evenly over the surface of the agar using a sterile L-shaped spreader or glass rod.

Incubate the plates at a temperature of 301.15–303.15 Kelvin (28–30°C) for 86,400 to 172,800 seconds (24–48 hours) in an incubator.

Observation and Selection of Colonies

After incubation, observe the growth on the plates. Colonies of Pseudomonas typically appear greenish, bluish, oryellowish, depending on the pigment produced. Some species, like P. aeruginosa, produce a fluorescent pigment called pyoverdine, which glows under UV light. Carefully observe and select colonies with characteristic pigment, smooth texture, and round shape for further analysis.

Sub-culturing for Pure Culture

Pick a single, well-isolated colony using a sterile inoculating loop and streak it onto a fresh nutrient agar plate to obtain a pure culture. This step ensures that only one type of bacterium is grown without contamination from others.

Incubate the plate at a temperature of 301.15–303.15 kelvin (28–30°C) for 86,400 seconds (24 hours).

Gram Staining Procedure

To perform Gram staining, prepare a bacterial smear on a clean glass microscope slide using a sterile loop. Allow the smear to air dry, then heat-fix it by quickly passing the slide through a flame several times.

Primary stain: Apply crystal violet and let it sit for 60 seconds (1 minute).

Mordant: Rinse briefly with distilled water, then apply Gram’s iodine for 60

Decolorization: Rinse with water, then applies95% ethanoldrop wise for 10–30 seconds (until runoff is clear).

Counterstain: Rinse again, and then apply safranin for 60

Perform a final rinse with water and gently blot the slide dry using bibulous

Finally, examine the slide under a light microscope using objective lenses of 10×, 40×, and 100× (oil immersion) to observe bacterial morphology and Gram reaction.18

Biochemical tests

A series of standard biochemical tests including Indole, Methyl Red, Voges- Proskauer, Citrate (IMViC), and Triple Sugar Iron (TSI) are used to differentiate members of the Enterobacteriaceae family. Though Pseudomonas is not an Enterobacteriaceae member, these tests help distinguish it from other Gram-negative rods based on metabolic characteristics.

Molecular Identification – DNA-Based Method

DNA Extraction

Extract genomic DNA from a pure Pseudomonas culture using a commercial DNA extraction kit, following the manufacturer’s protocol. Ensure high-quality, contaminant-free DNA.19

PCR Amplification

Prepare a Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) mix with the extracted DNA as the template. Use primers specific to the 16S rRNAgene of Pseudomonas spp.20

Gel Electrophoresis

Prepare a 1–2% agarose gel in 1× TAE

Load PCR products mixed with loading dye into the

Include a DNA ladderfor size

Run the gel at 50–150 volts until bands are

Stain with ethidiumbromide , SYBR Safe, and visualize under UV light.

A clear band at the expected base pair size confirms successful 21

Sequencing

Purify the PCR productandsend forSanger sequencing.Analyze the sequenceusing NCBI BLASTto confirm species-level identification.22

Extraction of Tryptanthrin from Pseudomonas spp.

Culture Preparation

Inoculate Pseudomonas into a suitable culture medium and incubate under optimal conditions (usually at ~303 K (30°C)for (24–48 hours).

Extraction Process

Harvest the culture by

Resuspend the cell pellet in ethyl acetate (CH₃COOC₂H₅).

Shake or vortex for 300–600 seconds (5–10 minutes).

Separate the solvent layer, which contains

Evaporate the solvent using a rotary evaporator to concentrate the.

Purification

Use column chromatography with silica gel as the stationary

Elute with a gradient solvent system (e.g., hexane ethyl acetate) to separate

Collect and monitor fractions under UV light using Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC).

Final Purification

Use preparative HPLC to further purify tryptanthrin.

Characterization

Confirm compound identity using spectroscopic methods:

UV-Vis spectroscopy (wavelength in nanometers),

Infrared (IR) spectroscopy (wave number in cm⁻¹),

NMR spectroscopyfor structural confirmation23.

Chemical Synthesis of Tryptanthrin

Preparation of Isatin

React indole with concentratedsulfuricacid(H₂SO₄) using the

Heat the mixture under reflux (~360–370 K or 87–97°C)forseveral hours (~10,800– 14,400 seconds).

Cool the mixture, pour into water, and extract isatin using an organic solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate).

Wash the organic layer with water, dry over anhydrous sodium sulfate (Na₂SO₄), and evaporate the solvent under reduced pressure (~10–30 kPa)to get crude isatin.24

Synthesis of Tryptanthrin

Mixisatin, indole, glacial acetic acid, and aceticanhydride in a

Add a small amount of sodiumacetate as a

Heat under reflux (~360–370 K) for

Cool and pour the mixture into water to

Filter and wash the solid with water to remove 25

Purification

Dissolve crude tryptanthrin in ethylacetate (CH₃COOC₂H₅).

Use silica gel column chromatography, eluting with solvents of increasing polarity (hexane:ethyl acetate mixtures).

Use TLC (Thin Layer Chromatography) to monitor and collect desired

Evaporate under reduced pressure to obtain purified tryptanthrin.

Characterization

Use spectroscopic techniques like:

UV-Vis spectroscopy (wavelength in nanometers),

IR spectroscopy (wavenumber in cm⁻¹),

NMR spectroscopy (chemical shifts in ppm) to confirm structure and purity of

Molecular Docking of Tryptanthrin with Cancer Targets

Preparation of Protein and Ligand

Download 3D structures of target cancer proteins from protein

Clean structures using molecular modelling software:

Remove water molecules and non-protein

Add polar hydrogens, fix missing atoms, and optimize

Optimize 3D structure of tryptanthrinligand using computational

Docking Simulation

Load prepared protein and ligand into docking software (AutoDock, PyRx.).

Define the docking grid around the protein’s active

Run docking simulations using proper scoring

Generate multiple poses and analyze:

Binding energy (kJ/mol),

Hydrogen bonds,

Hydrophobic interactions.

Visualization and Analysis

Use visualization tools to observe ligand–protein interactions.

Prioritize poses with strong binding

Perform

Molecular dynamics simulations

Free energy 26

Results

Pseudomonas bacteria were isolated and identified their appurtenance and stained on microscope.

Tryptanthrin

|

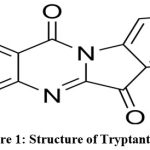

Figure 1: Structure of Tryptanthrin |

The study investigates the binding affinity of tryptanthrin (Fig: 1) with the melonama protein, a cancerous protein, using a docking study involving the protein structure downloaded from the RCSB site.

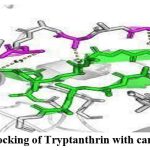

Docking of Tryptanthrin with cancer protein

The docking showed that Tryptanthrin and its derivatives have the potential to bind with melanoma cancer protein. It can be further used for the treatment of cancerous effects (Fig: 2).

|

Figure 2: Docking of Tryptanthrin with cancer protein |

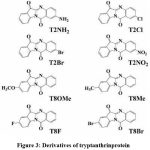

Through GC/MS,LCMS analysis totally eight derivatives of tryptanthrin was identified they are,

|

Figure 3: Derivatives of tryptanthrinprotein |

All the derivatives of tryptanthrin shows various anti-microbial anti-fungal characteristic against various pathogens (Fig:3).

|

Table 1: Derivatives of tryptanthrinprotein |

|

Figure 4: TLC plating for the separation of compounds prior to GCMS analysis. |

Discussion

This study investigates the anticancer potential of tryptanthrin and its derivatives derived from Pseudomonas aeruginosa, utilizing in vitro assays and in silico drug design approaches. Our findings support the bioactivity of these compounds and their potential role as lead structures in anticancer drug development. Tryptanthrin and its derivatives demonstrated significant binding affinities toward cancer-related targets. Molecular docking revealed strong interactions with topoisomerase IIα and EGFR, with tryptanthrin showing a binding energy of –9.3 kcal/mol and its methylated derivative (T-3) exhibiting –10.1 kcal/mol. GC-MS profiling confirmed the presence of tryptanthrin (RT: 18.7 min, 96% similarity index), along with structurally related derivatives. MTT assays showed dose- dependent cytotoxicity on MCF-7 and HeLa cell lines, with IC₅₀ values ranging from 12.4 to 24.6 μM, indicating promising in vitro anticancer activity.27

Despite the encouraging results, this study has limitations. The dependency on molecular docking does not fully capture the dynamic behavior of molecules in physiological conditions. Additionally, the absence of in vivo validation limits our ability to assess pharmacokinetics, systemic toxicity, and therapeutic efficacy. Further studies using animal models and ADME analysis are necessary for translational insights.Our findings contribute to the growing body of research exploring microbial alkaloids as anticancer agents. While tryptanthrin has been previously studied from plant sources, its isolation from P. aeruginosahighlights a novel microbial route with biotechnological potential. This work supports the utility of combining microbial bio-prospecting with computational and experimental drug design to discover new leads for cancer therapy.28

Conclusion

Finally, the study emphasizes the importance of tryptanthrin and its derivatives from Pseudomonas spp. in the battle against cancer. This study contributes to ongoing anti-cancer drug development efforts by taking a synergistic approach that includes experimental investigations and computational modelling. There is hope that by deciphering the mechanisms of action and refining the pharmacological properties of tryptanthrin derivatives, novel and effective cancer treatments can be developed. Continued research and innovation in this discipline hold the possibility of transforming natural products into clinically effective anti-cancer medications, ultimately benefiting patients worldwide.

Acknowledgement

Wethank TNSCST Government of TamilNadu for instrumentation facilities provided to the Department of Microbiology, AVS College of Arts and Science (Autonomous), Salem. We also thank Dr. I. Carmel Mercy Priya, Principal, Dr. S. S. Maithili, Vice Principle and Thiru. K. Rajavinayagam, Secretary, AVS College of Arts and Science (Autonomous), Salem.

Funding Sources

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

This statement does not apply to this article.

Ethics Statement

This research did not involve human participants, animal subjects, or any material that requires ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not involve human participants, and therefore, informed consent was not required.

Clinical Trial Registration

This research does not involve any clinical trials.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

Not Applicable

Author Contributions

D. (Manoj Dhandapani): Data Collection, Analysis, Writing – Review & Editing.

D. (Dheepan George): Methodology, Writing – Original Draft, Visualization, Supervision, Project Administration.

References

- Crone,S.,Vives‐Florez,M.,Kvich,L.,Saunders,A.M.,Malone,M.,Nicolaisen,M.H., Bjarnsholt, T. The environmental occurrence of PseudomonasaeruginosaJournal of Pathology, Microbiology and Immunology–the APMIS 2025;133(3)220- 231https://doi.org/10.1111/apm.13010.

CrossRef - Fair,R. , Tor,YAntibioticsandbacterialresistance inthe21st century. Perspective in Medical Chemistry volume: 2014(6)https://doi.org/10.4137/PMC.S14459.

CrossRef

- Dias, A., Urban, S., Roessner, U.Ahistorical overview of naturalproducts in drugdiscovery, Metabolites.2012; (2) 2303 – 336https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo2020303.

CrossRef

- Gillespie,D.E.,Brady,S.F.,Bettermann,A.D.,Cianciotto,N.P.,Liles,M.R.,Rondon, M. R., Handelsman, J. Isolation of antibiotics turbomycin A and B from a metagenomic library of soil microbial DNA.Applied and environmental microbiology,2002 ;68(9),4301-4306 https://doi.org/10.1128/ AEM.68.9. 43014306.2002.

CrossRef

- Leisinger,T.,Margraff,R..Secondary metabolites of the fluorescent Microbiological 1979; 43(3), 422-442.

CrossRef - Jahng,K.C.,Kim,S.I.,Kim,D.H.,Seo,C.S.,Son,J.K.,Lee,S.H., Jahng,Y.One-pot synthesis of simple alkaloids: 2, 3-polymethylene-4 (3H)-quinazolinones, luotoninA, tryptanthrin, and rutaecarpine. Chemicaland PharmaceuticalBulletin, 2008; 56(4), 607-609.https://doi.org/10.1248/cpb.56.607.

CrossRef

- Leisinger,T.,Margraff,R..Secondary metabolites of the fluorescent Microbiological 1979; 43(3), 422-442.

CrossRef - M Campos, J. C. D., Antunes, L. C., Ferreira, R. BGlobal priority pathogens: virulence, antimicrobial resistance and prospective treatment options. Future microbiology,2020;15(8),649-677 https://doi.org/10.2217/fmb-2019-0333.

CrossRef

- Jahng, Y. Progress in the studies on tryptanthrin, an alkaloid of history.Archives of pharmacalresearch, 2013;36,517-535.https://doi.org/10.1007/s12272-013-0091-9.

CrossRef - Jensen, P. R..Naturalproducts and the gene cluster revolution.Trends in microbiology ,2016;24(12),968-977.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2016.07.006.

CrossRef - Newman, D. J., Cragg, G. M. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the 30 years from 1981 to 2010. Journal of natural products, 2012;75(3), 311-335. https://doi.org/10.1021/np200906s.

CrossRef - Peix, A., Ramírez-Bahena, M. H., Velazquez, EHistorical evolution and current status of the taxonomy of genus PseudomonasInfection, genetics and evolution . (2009).9(6),1132-1147 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2009.08.001.

CrossRef

- Reen, F. J., Romano, S., Dobson, D., OGara, F. The sound of silence: activating silentbiosyntheticgeneclustersinmarinemicroorganisms. Marine drugs, 2015;13(8),4754-4783.https://doi.org/10.3390/md13084754.

CrossRef

- Mlot, Antibiotics in nature: beyond biological warfare. 2009; 324(5935), 1637- 1639 DOI: 10.1126/science.324_1637.

CrossRef - Oconnor,K.E.,Hartmans,S.Indigoformation by aromatic hydro carbon-degrading Biotechnology Letters, 1998;20,219- 223.,https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005361415496.

CrossRef - Praveen, I. J., Parameswaran, P. S., Majik, M. S. Bis (indolyl) methane alkaloids: isolation, bioactivity, and synthesis. Synthesis 2015;47(13):1827-1837 DOI: 1055/s-0034-138041.

CrossRef - Shimazaki, Y., Yajima, T., Takani, M., Yamauchi, O. Metal complexes involving indole rings: Structures and effects of metal–indole interactions. Coordination ChemistryReviews,2009;253(3-4),479- 492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2008.04.012

CrossRef - Takeshige, , Egami, Y., Wakimoto, T., Abe, I. Production of indole antibiotics induced by exogenous genederived from spon gemetagenomes. Molecular BioSystems, 015;11(5),1290-1294.DOI: 10.1039/C5MB00131E.

CrossRef

- Cappuccino, J.G., Welsh, C. Microbiology: A Laboratory Manual (12th ). Pearson Education 2019.

- Wilson, Preparation ofgenomic DNA from bacteria.In Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Wiley.2001;(56) 241-245.https://doi.org/10.1002/0471142727.mb0204s56.

CrossRef - Lane, D. J. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing. In Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics1991; 115–175. Wiley.

- Sambrook, J., Russell, D. W. (2001). Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual (3rd ed). Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. 2001.https://doi.org/10.1590/S0036- 46652014000100004

- Altschul, S. F., Gish,W.,Miller, , Myers, E.W., Lipman, D.J. Journal of Molecular Biology, 1990;215(3), 403–410. https://support.nii.ac.jp/en/news/cir/20231031.

CrossRef - Bhatnagar, I., Kim, S. K. Immense essence of excellence: marine microbial Marine Drugs, 2010;8(10), 2673– 2701. https://doi.org/10.3390/md8102673.

CrossRef - Shriner, R. L., Hermann, C. K. F., Morrill, T. C., Curtin, D. Y., Fuson, R. C. The Systematic Identification of Organic Compounds (8th ed.). 2003;Wiley.

- Zhang, J., Li, H., Liu, Y. An efficient synthesis of tryptanthrin derivatives and their biological evaluation. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters, 2011;21(23), 6999–7003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.09.094.

CrossRef

- Morris, G. M., Huey, R., Olson, A. J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. Journal of Computational Chemistry, 2008;30(16), 2785–2791. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.21256.

CrossRef

- Harada, T.,. “Anticancer activity of tryptanthrin and its derivatives.” Journal of Natural Products, 2012;75(4), 624-629. doi: 3390/ijms24021450.

CrossRef

Abbreviations

PCR- Polymerase Chain Reaction,

TAE- Tris Acetate EDTA,

TLC- Total Lymphatic Cell,

HPLC-High Performance Liquid Chromatography,

NMR-Nuclear Magnetic Resonance,

IR- Infrared Radiation,

LCMS-Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry,

GCMS-Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.