Manuscript accepted on : 18-09-2025

Published online on: 29-09-2025

Plagiarism Check: Yes

Reviewed by: Dr. Mostafa Norizadeh

Second Review by: Dr. Mahmoud Mohamed Elalfy Elhefnawy and Dr. Sura Maan Salim

and Dr. Sura Maan Salim

Final Approval by: Dr. Eugene A. Silow

Shashikala Metri1* , Rohini Rasamallu2

, Rohini Rasamallu2 , Ceema Mathew3

, Ceema Mathew3 , Ganga Raju Mudunuri2

, Ganga Raju Mudunuri2 and Shaheda Mohammad2

and Shaheda Mohammad2

1Department of Pharmacognosy, Gokaraju Rangaraju College of Pharmacy, Hyderabad, India.

2Department of Pharmacology, Gokaraju Rangaraju College of Pharmacy, Hyderabad, India.

3Department of Pharmaceutical Analysis, Gokaraju Rangaraju College of Pharmacy, Hyderabad, India.

Corresponding Author E-mail:shashikala8052@grcp.ac.in

ABSTRACT: The liver plays crucial role in metabolic homeostasis, detoxification, and biosynthesis, yet it is highly susceptible to damage from xenobiotics, alcohol, metabolic disorders, and infections. Hepatotoxicity, a major contributor to liver disease, progresses from reversible steatosis to irreversible cirrhosis, driven by genetic, environmental, and metabolic factors. Early detection and monitoring of liver injury rely heavily on biomarkers, with conventional options such as aspartate aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase, bilirubin, and gamma-glutamyl transferase being widely used but limited in specificity. Recent advances in omics technologies have uncovered novel biomarkers, including microRNAs, high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), keratin-18, and glutamate dehydrogenase that provide enhanced sensitivity and earlier detection. This review consolidates current knowledge on conventional, emerging, and omics-based biomarkers, exploring their mechanistic roles and clinical potential. Broader adoption of validated biomarker panels could enhance diagnostic accuracy, guide treatment strategies, and ultimately enhance results for liver disease patients.

KEYWORDS: ALT; AST; Biomarkers; Clinical diagnostics; Hepatotoxicity; Hepatic injury; HMGB1; microRNAs; Omics

| Copy the following to cite this article: Metri S, Rasamallu R, Mathew C, Mudunuri G. R, Mohammad S. Comprehensive Review on Biomarkers in Hepatotoxicity: From Conventional Indicators to Omics Driven Discoveries. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(3). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Metri S, Rasamallu R, Mathew C, Mudunuri G. R, Mohammad S. Comprehensive Review on Biomarkers in Hepatotoxicity: From Conventional Indicators to Omics Driven Discoveries. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(3). |

Introduction

The liver is the principal organ essential for metabolizing proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids. Working alongside the spleen, it facilitates elimination of senescent red blood cells, produces bile for digestion, and synthesizes plasma proteins and lipoproteins, including clotting factors.1 It performs numerous critical functions that maintain the body’s equilibrium and overall well-being. Proper liver function is indispensable for nearly all essential metabolic processes, including growth, immune response, nutrient metabolism, energy production, and reproduction.2 Most hepatotoxic substances damage liver cells by inducing lipid peroxidation, oxidative stress, and elevating serum biomarkers such as alkaline phosphatase, transaminases, bilirubin, triglycerides, and cholesterol.3,4

Following are the key functions performed by liver

Regulating nutrient absorption and metabolismfrom the intestines.

Modulating endocrine functionsto facilitate growth and development.

Maintaining energy metabolism (e.g., glycogen storage and gluconeogenesis.

Synthesizing and biotransforming proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids.

Regulating fluid and electrolyte balance.

Producing bile for digestion and eliminating hydrophobic compounds.

Supporting immune function via Kupffer cells and acute-phase proteins.

Detoxifying drugs and xenobiotics through enzymatic metabolism.

The liver synthesizes approximately 15% of the body’s total proteins, with most being secreted directly into the bloodstream. This process begins when transcription factors activate promoter sequences in the DNA, initiating gene expression. Following translation and post-translational modifications, the newly synthesized proteins are released from the sinusoidal surface of hepatocytes into the circulation. Hepatic protein production is tightly regulated by nutritional status and hormonal signals. Among the liver’s diverse protein products, are albumin (maintains oncotic pressure and transports molecules) ceruloplasmin (copper transport and oxidation) coagulation factors (fibrinogen, prothrombin, etc.) and fibrinolytic proteins, complement system proteins (immune defense), protease inhibitors (e.g., α1-antitrypsin). Notably, C-reactive protein (CRP), a key acute-phase reactant, is the most commonly measured hepatic protein in clinical practice. While the liver does not store proteins, it efficiently recycles amino acids to sustain ongoing protein synthesis.5

Global Burden

Alcohol-associated Liver Disease

Global annual per capita alcohol consumption (2016) reached 6.4 liters, with 5.1% of the worldwide population affected by alcohol use disorder. Alcohol remains the leading cause of cirrhosis globally, accounting for nearly 60% of cases in North America, Europe, and Latin America. In recent years, the incidence of alcohol-associated hepatitis has risen significantly particularly among young adults and women. Given the synergistic interaction between alcohol consumption and metabolic risk factors, Europe and North America face a heightened risk of increasing liver disease burden in coming years.

Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

It impacts approximately 32.4% of people worldwide. Its contribution to global mortality has increased from 0.9% to 0.16% of all deaths. Currently NAFLD ranks as the second most common cause of liver transplants overall and the leading cause in women. Emerging metabolic risk factors in children and adolescents represent one of the most significant impending threats to global health.6

Various Stages of Hepatotoxicity

Hepatotoxicity progresses through distinct clinical stages, with severity and manifestations varying based on etiology including alcohol abuse, metabolic dysfunction, or drug-induced injury, and outlined in Table 1 and Figure 1.

Table 1: Clinical stages of hepatotoxicity and their common etiological factors

| Stage | Description | Causes/Associations | |

| Normal liver | Healthy liver with intact structure; normal metabolism, detoxification, and synthesis. | – | |

| Fatty liver (Steatosis) | Reversible fat accumulation within hepatocytes. | Poor diet, obesity, alcohol, certain drugs. | |

| NAFLD | Fatty liver related to obesity, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome. | Sedentary lifestyle, high-calorie intake. | |

| SMAFLD | Fatty liver due to both metabolic issues and alcohol use. | Combined metabolic syndrome + alcohol consumption. | |

| AFLD | Fatty liver caused by prolonged excessive alcohol intake. | Chronic alcohol abuse. | |

| Steatohepatitis | Fat buildup with inflammation and liver cell injury. | Progression of fatty liver disease. | |

| NASH / MASH | Steatohepatitis associated with non-alcoholic or metabolic dysfunction | NAFLD progression with inflammation. | |

| ASH | Alcoholic steatohepatitis. | Chronic heavy drinking. | |

| SMASH | Steatohepatitis from metabolic dysfunction plus alcohol intake. | Metabolic syndrome + alcohol abuse. | |

| Cirrhosis | Irreversible fibrosis with regenerative nodules; severe functional loss; risk of liver failure or cancer. | Chronic liver injury from any cause. | |

|

Figure 1: The sequential phases of hepatic damage in liver toxicity7 |

Risk factors of hepatotoxicity

Multiple variables influence hepatotoxicity risk, idiosyncratic factors, age, sex, lifestyle exposures like alcohol intake, smoking, pre-existing liver illness, concurrent use of other medicines, and genetic and environmental influences [Figure 2].8,9 Mitochondrial dysfunction, impairing energy metabolism, or aberrant lipid metabolism through beta-oxidation have all been linked to the mechanisms of hepatotoxicity.10,11

|

Figure 2: Common predisposing factors for liver toxicity |

Biomarkers in Hepatotoxicity

Definition and Classification:

The NIH defines a biomarker as “a characteristic that is objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biologic processes, pathogenic processes, or pharmacologic responses to therapeutic intervention”.12 Biochemical markers can be classed based on their purpose (Table 2).

Table 2: Biomarkers based on their purpose

| Biomarker type | Definition | Purpose |

| Type 0–Prognostic biomarkers | Indicators of illness risk or natural progression | Predict the likelihood of disease onset or monitor its natural course |

| Type 1–Response biomarkers | Characterize biological activity in response to treatment interventions | Assess physiological or molecular changes induced by therapy |

| Type 2–Surrogate efficacy biomarkers | Determine clinical outcomes and treatment efficacy | Serve as substitutes for direct clinical endpoints in evaluating treatment success |

| Pharmacodynamic biomarkers | Biological response in a patient after exposure to a medical product | Demonstrate target engagement, confirm drug activity, and guide dose optimization |

Biomarkers serve as valuable diagnostic tools in clinical hepatology, complementing other methods to accurately detect liver conditions such as DILI (drug-induced liver injury) and HILI (herbal medicine–induced liver injury) are commonly studied using biomarkers. These indicators usually involve the detection of RNA, DNA, or protein molecules in biological samples, including blood, plasma, and urine.13-20 The development and implementation of new biomarkers require rigorous validation through testing in confirmed patient populations and comparison with existing diagnostic standards.16 This ensures their diagnostic accuracy and reproducibility, which clearly differentiate between healthy and sick states and deliver consistent results across laboratories and populations.14,20

When properly validated, these biomarkers become essential for early detection of hepatotoxicity, monitoring disease progression, guiding treatment decisions, and ultimately improving patient safety in cases of suspected DILI or HILI.

Conventional Biomarkers

Conventional biomarkers for evaluating liver injury can be classified into two primary categories: (a) markers of impaired liver function or homeostasis, and (b) markers of cellular damage. The liver maintains critical physiological functions including protein synthesis, bile acid metabolism, and waste excretion examples include bilirubin and urea. Changes may also be observed in circulating bile acids, overall bilirubin levels, and blood proteins – frequently observed following hepatotoxic drug exposure or in liver disease – serve as well-established indicators of compromised hepatic function.

Indicators of liver cell damage are usually enzymes that leak into the bloodstream when hepatocytes are injured or undergo necrosis. Common examples are alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), and glutamate dehydrogenase (GLDH).21 Additional biochemical parameters such as albumin levels, total protein, triglycerides, and coagulation markers (particularly PT/INR) provide valuable assessment of hepatic synthetic capacity, especially in chronic liver disease.22, 23

Standard biochemical markers (Table 3) outline the routine laboratory parameters evaluated during preclinical assessment of drug-related liver toxicity.

Table 3: Principal conventional biomarkers used in the assessment of liver injury

| Biomarker | Organ distribution | Diagnostic indication | Associated injury / Role | |

| AST | Found in liver, brain, heart and skeletal muscle | Released into circulation upon hepatocellular damage | Necrosis of hepatocytes | |

| TB (Total bilirubin) |

|

Indicator of hepatobiliary dysfunction; also elevated in hemolysis | Hepatic insufficiency, cholestasis, biliary injury. | |

| ALP | Found in diverse tissues | Sign of hepatobiliary impairment | Biliary stasis | |

| Clotting time | – | Increased with severe liver injury | Liver function | |

| GGT | Liver, pancreas and kidney | Leads to cholestasis and biliary injury | Cholestasis with biliary damage | |

| Bile salts | Secreted via bile ducts | Rises with liver injury and dysfunction | Altered function | |

| Protein levels | – | Declines with advanced liver damage | Reflects liver function | |

| ALT | Hepatocytes | Hepatocellular necrosis; may also rise in cardiac or muscle injury | Cellular death |

ALT and AST

ALT and AST are sensitive biomarkers of hepatocellular injury, with ALT being more liver-specific due to its predominant hepatic localization, while AST is widely distributed across tissues.24 Their differing plasma half-lives (ALT~47 h; AST~17 h) enhance diagnostic interpretation.25 Although elevations occur in hepatitis, alcohol-related liver disease, cirrhosis, and drug-induced injury, their limitation is poor specificity, as increases are also seen in muscle damage and myocardial infarction.26, 27

The study by Kunutsor et al. further noted that despite associations with cardiovascular outcomes, aminotransferases add little predictive value to CVD risk models, emphasizing the need to interpret them alongside other biomarkers and clinical findings.28

Gamma-glutamyl transferase

GGT is a validated marker of liver disease, biliary disorders, and chronic alcohol consumption.29 Elevated levels also correlate with increased risk of stroke, type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, and heart failure, even within the normal reference range.30,31 Biochemically, GGT regulates glutathione (GSH) turnover through the glutamyl cycle, influencing cellular redox balance.32,33 Its strength lies in its high sensitivity to hepatobiliary injury, oxidative stress, and alcohol intake; however, its major limitation is poor specificity, since elevations are also observed in obesity, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, and with certain medications. 34-38 In hepatic steatosis, increased GGT reflects oxidative stress–induced GSH depletion, compensatory enzyme upregulation, and inflammation, with fatty liver progression more common in patients with abnormal GGT.39-44 Persistent GGT elevation further predicts fatty liver risk, and in some hepatotoxicity cases, GGT may rise disproportionately compared with other enzymes.45

Alkaline Phosphatase

ALP exists in tissue-specific forms (placenta, germinal tissue, colon) and non–tissue-specific forms present in liver, bone, and kidney. 46 Physiologically, levels may rise during bone growth or pregnancy due to increased osteoblast or placental activity.47,48

Clinically, ALP is a useful and sensitive marker for cholestatic liver disorders, with about 75% of patients with intrahepatic or extrahepatic cholestasis showing enzyme levels fourfold above the upper limit of normal.49 A strength of ALP is its ability to detect biliary obstruction and cholestasis, even persisting for up to a week after resolution of obstruction.50 However, its limitation lies in poor specificity, since elevations also occur in bone disease, pregnancy, infiltrative liver conditions, and sepsis, making it necessary to interpret ALP alongside other biomarkers and clinical findings. 51

Glutamate dehydrogenase

GLDH is a mitochondrial matrix enzyme occurring predominantly in liver lobules, with smaller amounts in kidney, brain, intestine, and pancreas, and minimal presence in muscle.52-55 Its abundance in the liver’s matrix-rich mitochondria, coupled with low activity outside the liver, makes GLDH a highly specific marker of hepatocellular injury.56 Unlike ALT, which can be elevated in muscle disorders, GLDH remains unaffected, making it particularly valuable for detecting liver damage in patients with concomitant muscle disease.52,57 Its shorter plasma half-life (16–18 h) compared to ALT 52,54 also allows more accurate reflection of current hepatic injury. However, GLDH testing is not widely available in routine clinical practice, can be influenced by mitochondrial disorders, and is less validated in large patient populations, which limits its broader clinical application.

Alternative indicators of drug-related liver toxicity

Nuclear DNA and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) fragments have been investigated as both mechanistic markers and predictors of hepatotoxicity. Nuclear DNA fragments can be quantified by antihistone immune assays, while mtDNA is measured using quantitative PCR. In N‑acetyl‑para‑aminophenol (APAP) overdose, ALT, GLDH, and mtDNA levels increase in both mice and humans, with mtDNA potentially specific for mitochondrial injury.58

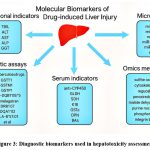

Several biomarkers are utilized to detect liver disease and assess the extent of hepatic injury. Some are disease-specific, while others represent general liver parameters that tend to rise across most liver disorders, as shown in [Figure 3].

|

Figure 3: Diagnostic biomarkers used in hepatotoxicity assessment |

Novel Biomarkers

MicroRNAs, especially miR-122 and miR-192, are considered highly promising biomarkers, as their levels increase in the blood of both mice and humans following APAP overdose, often preceding the rise of ALT.59,60 Similarly, HMGB1, a nuclear protein involved in transcription regulation, nucleosome organization, and DNA repair,61 acts as a marker of necrosis when measured in total form, and of inflammation when present in its acetylated form. Keratin‑18 (K18), a cytoskeletal protein, is cleaved by caspases during apoptosis to form a fragment recognized by the M30 antibody.62 Both total and cleaved K18 are elevated in APAP overdose, with total levels markedly higher in APAP and other hepatotoxicities, indicating that oncotic necrosis predominates.63-65Additional proteins such as argininosuccinate synthetase,66 paraoxonase‑1, glutathione‑S‑transferase (GST), liver‑type fatty acid binding protein‑1, cadherin‑5,67,68 macrophage colony‑stimulating factor receptor, and aldolase‑B are cAMP‑regulated and show potential as mechanistic markers. While some, such as macrophage colony‑stimulating factor receptor, have been proposed as inflammatory biomarkers, their role in hepatotoxicity remains under explored.69

Emerging Biomarkers and Omics Approaches

Several serum protein–based biomarkers have been explored for assessing liver injury, based on the leakage of hepatocellular proteins into circulation. Most remain experimental and are not yet qualified for routine use. ALT isozymes-ALT1 (mainly hepatic but also in renal and salivary tissue) and ALT2 (present in adrenal cortex, neurons, cardiac and skeletal muscle, and pancreas)—may help localize the source of injury.70

Other candidates include sorbitol dehydrogenase, glutamate dehydrogenase (GLDH), serum F protein, GST-alpha, and arginase I.71Sorbitol dehydrogenase marks acute hepatic injury in rodents; GLDH is highly liver-specific and unaffected by muscle injury; serum F protein correlates with histopathology in humans72 but lacks preclinical validation; GST-alpha reflects centrilobular damage but can be induced by xenobiotics; and arginase I rises earliest and most markedly after thioacetamide injury, paralleling ALT/AST.73,74

While these markers offer advantages in sensitivity or specificity, their limited validation and overlap with extrahepatic sources constrain their clinical application, and they may be most effective when used in panels with conventional enzymes. Emerging omics techniques provide additional promise: transcriptomics highlights gene-expression changes, proteomics enables broad protein profiling, and metabolomics captures metabolic disturbances, often preceding biochemical alterations. Collectively, these approaches could deliver biomarker panels with greater specificity, sensitivity, and earlier detection potential than current assays.

Transcriptomics has been widely applied in hepatotoxicity research to identify gene expression signatures associated with drug-induced liver injury (DILI). By revealing how hepatotoxins alter gene activation, transcriptomic profiling can uncover predictive patterns such as those linked to hepatic steatosis or oxidative stress pathways, providing early biomarkers and mechanistic insight into liver damage.

Proteomics complements transcriptomics by mapping protein-level changes in response to toxic injury. It highlights alterations in protein abundance and post-translational modifications that reflect hepatocellular stress and damage. As proteins are functional executors of gene expression, proteomic biomarkers help connect molecular changes with phenotypic outcomes, improving the diagnostic value for DILI.

Metabolomics offers a direct view of the hepatocellular state by capturing end products of biochemical pathways. It reveals actual metabolic disruptions during DILI, including mitochondrial dysfunction, bile acid imbalance, and energy metabolism defects. This approach enables earlier detection of injury and supports individualized risk assessment through metabolic phenotyping. 75-76

Cellular Stress Markers

The cellular stress response regulates hepatocyte survival or death after toxicant exposure. Proteomic methods such as two-dimensional gel electrophoresis, mass spectrometry and iTRAQ™ have identified stress-related markers in rat hepatocarcinogenesis, including annexins, metabolic enzymes, aflatoxin B₁ aldehyde reductase, and GST-P form. Keratin-18 indicates apoptosis and necrosis, while HMGB1 reflects necrosis and inflammation only. Malate dehydrogenase (MDH), purine nucleoside phosphorylase, and paraoxonase-1 correlate strongly with histopathology in hepatotoxicant-exposed rats; the first is elevated in hepatic and cardiac injury, the second rises early after galactosamine or endotoxin exposure, and the third, an HDL-associated hepatic enzyme, decreases in drug-induced and chronic liver injury. In humans, 92 altered serum proteins were identified in DILI, with apolipoprotein E distinguishing the cases from controls, with 89% accuracy. 77 The catalogue of emerging and omics-based biomarkers in hepatotoxicity, is given in Table 4.

Table 4: Catalogue of emerging and omics-based biomarkers in hepatotoxicity

| Proposed biomarker | Origin | Specimen | Clinical/Experimental Relevance |

| Proteomics | |||

| Interleukin-1, TNF- α | Kupffer cells (major) | Plasma | Hepatic cellular stress |

| GST-P | Liver cells | Serum | Liver cell damage |

| Keratin-18 | Epithelial cells | Serum | Marker of apoptosis or necrosis |

| HMGB1 | Multiple tissues | Serum | DILI and acute liver failure |

| Apolipoprotein E | Produced in the liver and many other tissues, including brain and kidney | Serum | Marker of drug-induced liver

injury |

| Metabolomics | |||

| Lactate | End product of anaerobic glycolysis | Serum/

Plasma |

Impaired heapatic clearence |

| Acylcarnitines | Mitochondrial β-oxidation | Serum/

Plasma |

Reflect mitochondrial dysfunction and altered lipid metabolism |

| Transcriptomics | |||

| lncRNAs (various) | Non-coding RNAs | Liver tissue/

Serum |

Regulatory roles in liver injury |

| miRNA-122 | Liver specific expression | Plasma | Viral-, alcohol-, and toxin-induced liver injury |

| miRNA-192 | Liver – enriched expression | Plasma | Chemical-induced

liver injury |

Conclusion

Biomarkers are indispensable for the timely detection, monitoring, and prognosis of hepatotoxicity. While conventional markers remain clinically valuable, their limitations necessitate the adoption of novel and omics‑based indicators that can enhance diagnostic specificity and enable earlier intervention. The future of hepatotoxicity assessment lies in integrated biomarker panels supported by high‑throughput, cost‑effective technologies and robust validation protocols. Such advancements will not only refine clinical decision‑making but also improve therapeutic outcomes, ultimately reducing the global burden of liver disease.

Acknowledgement

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support and encouragement provided by Head of The Institution and Management of Gokaraju Rangaraju College of Pharmacy, Hyderabad.

Funding Sources

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

This statement does not apply to this article.

Ethics Statement

This research did not involve human participants, animal subjects, or any material that requires ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not involve human participants, and therefore, informed consent was not required.

Clinical Trial Registration

This research does not involve any clinical trials.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

Not Applicable

Author Contributions

Shashikala Metri – Wrote the final draft of the work and edited, supervised the entire work.

Rohini Rasamallu & Shaheda Mohammad – Completed all reference work and formatting.

Rohini Rasamallu & Shaheda Mohammad – Collected all the data and completed the literature review.

Mudunuri Ganga Raju – Provided valuable guidance.

Shashikala Metri & Ceema Mathew – Data editing.

References

- Moritz A. The liver and gallbladder miracle cleanse: an all-natural, at-home flush to purify and rejuvenate your body. Ulysses Press; 2007.

- Sardesai V. Introduction to Clinical Nutrition. London UK: CRC Press; 2011. https://doi.org/10.1201/b16601

CrossRef - Shanmugam G, Ayyavu M, Rao DM, Devarajan T, Subramaniam G. Hepatoprotective effect of Caralluma umbellata against acetaminophen induced oxidative stress and liver damage in rat. J Pharm Res. 2013;6(3):342-5. https://doi.org/10.15171/bi.2018.04

CrossRef - Subramaniam S, Hedayathullah Khan HB, Elumalai N, Sudha Lakshmi SY. Hepatoprotective effect of ethanolic extract of whole plant of Andrographis paniculata against CCl4-induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Comparative Clinical Pathology. 2015 Sep;24(5):1245-51. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00580-015-2067-2

CrossRef - Moore KL, Dalley AF. Clinically oriented anatomy. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. 1209 p.

- Devarbhavi H, Asrani SK, Arab JP, Nartey YA, Pose E, Kamath PS. Global burden of liver disease: 2023 update. J Hepatol. 2023;79(2):516-37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2023.03.017

CrossRef - Senussi NH, McCarthy DM. Simultaneous metabolic and alcohol-associated fatty liver disease (SMAFLD) and simultaneous metabolic and alcohol-associated steatohepatitis (SMASH). Ann Hepatol. 2021;24:100526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aohep.2021.100526

CrossRef - Fisher K, Vuppalanchi R, Saxena R. Drug-induced liver injury. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139(7):876-887. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2014-0214-RA

CrossRef - Kwok R, Tse YK, Wong GH, Ha Y, Lee AU, Ngu MC, Chan HY, Wong VS. Systematic review with meta‐analysis: non‐invasive assessment of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease–the role of transient elastography and plasma cytokeratin‐18 fragments. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2014 Feb;39(3):254-69. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.12569

CrossRef - Pessayre D, Fromenty B, Berson A, et al. Central role of mitochondria in drug-induced liver injury. Drug Metab Rev. 2012;44(1):34-87. https://doi.org/10.3109/03602532.2011.604086

CrossRef - Pessayre D, Mansouri A, Berson A, Fromenty B. Mitochondrial involvement in drug-induced liver injury. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2010;(196):311-65. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-00663-0_11

CrossRef - Plourde G. Biomarkers in health product development: commentary. Int J Drug Saf. 2018;2(2):2.

- Yang X, Salminen WF, Schnackenberg LK. Current and emerging biomarkers of hepatotoxicity. Curr Biomark Find. 2012;2:43-55. https://doi.org/10.2147/CBF.S27901

CrossRef - Senior JR. Editorial. New biomarkers for drug-induced liver injury: are they really better? What do they diagnose? Liver Int. 2014;34:325-7. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.12384

CrossRef - Liu Y, Li P, Liu L, Zhang Y. The diagnostic role of miR-122 in drug-induced liver injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(49):e13428. https://doi.org/10.1097/ MD.0000000000013478

CrossRef - Teschke R, Schulze J, Eickhoff A, Danan G. Drug-induced liver injury: can biomarkers assist RUCAM in causality assessment? Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(4):803. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18040803

CrossRef - Kumana CR, Ng M, Lin HJ, Ko W, Wu PC, Todd D. Herbal tea induced hepatic veno-occlusive disease: quantification of toxic alkaloid exposure in adults. Gut. 1985;26:101-4. https://doi.org/10.1136/ gut.26.1.101

CrossRef - Teschke R, Larrey D, Melchart D, Danan G. Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) and herbal hepatotoxicity: RUCAM and the role of novel diagnostic biomarkers such as microRNAs. Medicines (Basel). 2016;3(3):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicines3030018

CrossRef - Teschke R. Idiosyncratic DILI: analysis of 46,266 cases assessed for causality by RUCAM and published from 2014 to early 2019. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:730. https://doi.org/10.3389/ fphar.2019.00730

CrossRef - Davis MA, Eldridge S, Louden C. Handbook of toxicologic pathology. 3rd ed. In: Haschek W, Rousseaux C, editors. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2013.

- Boone L, Meyer D, Cusick P, et al. Selection and interpretation of clinical pathology indicators of hepatic injury in preclinical studies. Vet Clin Pathol. 2005;34(3):182-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-165X.2005.tb00041.x

CrossRef - Evans GO. Animal clinical chemistry: a practical handbook for toxicologists and biomedical researchers. Florida (USA): CRC Press; 2009. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420080124

CrossRef - Temple R. Hy’s law: predicting serious hepatotoxicity. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15(4):241-3. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.1211

CrossRef - Thapa BR, Walia A. Liver function tests and their interpretation. Indian J Pediatr. 2007;74:663-71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-007-0118-7

CrossRef - Kwo PY, Cohen SM, Lim JK. ACG clinical guideline: evaluation of abnormal liver chemistries. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(1):18-35. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2016.517

CrossRef - Bradbury MW, Stump D, Guarnieri F, Berk PD. Molecular modeling and functional confirmation of a predicted fatty acid binding site of mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase. J Mol Biol. 2011;412(3):412-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2011.07.034

CrossRef - Pratt DS, Kaplan MM. Evaluation of abnormal liver-enzyme results in asymptomatic patients. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(17):1266-71. https://doi.org/1056/NEJM200004273421707

CrossRef - Kunutsor SK, Bakker SJ, Kootstra-Ros JE, Blokzijl H, Gansevoort RT, Dullaart RP. Inverse linear associations between liver aminotransferases and incident cardiovascular disease risk: the PREVEND study. Atherosclerosis. 2015 Nov 1;243(1):138-47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis. 2015.09.006

CrossRef - Koenig G, Seneff S. Gamma-glutamyl transferase: a predictive biomarker of cellular antioxidant inadequacy and disease risk. Dis Markers. 2015;2015:2-14. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/818570

CrossRef - Whitfield J. Gamma glutamyl transferase. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2001;38(4):263-355. https://doi.org/10.1080/20014091084227

CrossRef - Dhingra R, Gona P, Wang TJ, et al. Serum γ-glutamyl transferase and risk of heart failure in the community. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30(9):1855-60. https://doi.org/10.1161/ atvbaha.110.207340

CrossRef - Corti A, Duarte TL, Giommarelli C, et al. Membrane gamma-glutamyl transferase activity promotes iron-dependent oxidative DNA damage in melanoma cells. Mutat Res. 2009;669(1-2):112-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2009.05.010

CrossRef - Devi PR, Kumari SK, Kokilavani C. Effect of Vitex negundo leaf extract on the free radicals scavengers in complete Freund’s adjuvant induced arthritic rats. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2007;22:143-7. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02912899

CrossRef - Aberkane H, Stoltz JF, Galteau MM, Wellman M. Erythrocytes as targets for gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase initiated pro-oxidant reaction. Eur J Haematol. 2002;68(5):262-71. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0609.2002.01636.x

CrossRef - Stefano GB, Kream RM. Nitric oxide regulation of mitochondrial processes: commonality in medical disorders. Ann Transplant. 2015;20:402-7. https://doi.org/10.12659/AOT.894289

CrossRef - Emdin M, Pompella A, Paolicchi A. Gamma-glutamyltransferase, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular disease: triggering oxidative stress within the plaque. Circulation. 2005;112(14):2078-80. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.105.571919

CrossRef - Pompella A, Emdin M, Passino C, Paolicchi A. The significance of serum γ-glutamyltransferase in cardiovascular diseases. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2004;42(10):1085-91. https://doi.org/10.1515/ cclm.2004.224

CrossRef - Jarcuska P, Janicko M, Drazilova S, et al. Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase level associated with metabolic syndrome and proinflammatory parameters in the young Roma population in eastern Slovakia: a population-based study. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2014;22(Suppl):S43-50. https://doi.org/10.21101/cejph.a3901

CrossRef - Clark JM, Brancati FL, Diehl AM. The prevalence and etiology of elevated aminotransferase levels in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(5):960-7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07486.x

CrossRef - Loguercio C, De Simone T, D’Auria M, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a multicentre clinical study by the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36(6):398-405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2004.01.022

CrossRef - Fishbein MH, Miner M, Mogren C, Chalekson J. The spectrum of fatty liver in obese children and the relationship of serum aminotransferases to severity of steatosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;36(1):54-61. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005176-200301000-00012

CrossRef - Kain K, Carter AM, Grant PJ, Scott EM. Alanine aminotransferase is associated with atherothrombotic risk factors in a British South Asian population. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6(5):737-41. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.02935.x

CrossRef - Adams LA, Angulo P, Lindor KD. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. CMAJ. 2005;172(7):899-905. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.045232

CrossRef - Fujii H, Ko T, Fukuma T, et al. Frequently abnormal serum gamma-glutamyl transferase activity is associated with future development of fatty liver: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20(1):1-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-020-01369-x

CrossRef - Weber S, Allgeier J, Denk G, Gerbes AL. Marked increase of gamma-glutamyltransferase as an indicator of drug-induced liver injury in patients without conventional diagnostic criteria of acute liver injury. Visc Med. 2022;38(3):223-8. https://doi.org/10.1159/000519752

CrossRef - Azpiazu D, Gonzalo S, Villa-Bellosta R. Tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase and vascular calcification: a potential therapeutic target. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2019;15(2):91-5. https://doi.org/10.2174/1573403×14666181031141226

CrossRef - Zaher DM, El-Gamal MI, Omar HA, et al. Recent advances with alkaline phosphatase isoenzymes and their inhibitors. Arch Pharm (Weinheim). 2020;353(5):e2000011. https://doi.org/10.1002/ardp. 202000011

CrossRef - Masrour Roudsari J, Mahjoub S. Quantification and comparison of bone-specific alkaline phosphatase with two methods in normal and Paget’s specimens. Caspian J Intern Med. 2012;3(3):478-83.

- Sharma U, Pal D, Prasad R. Alkaline phosphatase: an overview. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2014;29:269-78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12291-013-0408-y

CrossRef - Green MR, Sambrook J. Alkaline phosphatase. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2020;2020(8):100768. https://doi.org/10.1101/pdb.top100768

CrossRef - Wiwanitkit V. High serum alkaline phosphatase levels, a study in 181 Thai adult hospitalized patients. BMC Fam Pract. 2001;2(1):1-4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-2-2

CrossRef - Schomaker S, Potter D, Warner R, et al. Serum glutamate dehydrogenase activity enables early detection of liver injury in subjects with underlying muscle impairments. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0229753. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229753

CrossRef - Kasarala G, Tillmann HL. Standard liver tests. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2016;8(1):13. https://doi.org/10.1002/cld.562

CrossRef - Macedo de Oliveira M. Implications of sex and extra-hepatic ammonia metabolism in chronic liver disease and development of hepatic encephalopathy [thesis]. Montreal: Université de Montréal; 2022. p.130-3.

- Mastorodemos V, Zaganas I, Spanaki C, et al. Molecular basis of human glutamate dehydrogenase regulation under changing energy demands. J Neurosci Res. 2005;79(1-2):65-73. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.20353

CrossRef - McGill MR, Jaeschke H. Biomarkers of mitotoxicity after acute liver injury: further insights into the interpretation of glutamate dehydrogenase. J Clin Transl Res. 2021;7(1):61.

- McMillan HJ, Gregas M, Darras BT, Kang PB. Serum transaminase levels in boys with Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy. Pediatrics. 2011;127(1):e132-6. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-0929

CrossRef - He Y, Feng D, Li M, et al. Hepatic mitochondrial DNA/toll-like receptor 9/microRNA-223 forms a negative feedback loop to limit neutrophil overactivation in acetaminophen hepatotoxicity in mice. Hepatology. 2017;66(1):220-34. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29153

CrossRef - Dear JW, Clarke JI, Francis B, et al. Risk stratification after paracetamol overdose using mechanistic biomarkers: results from two prospective cohort studies. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3(2):104-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-1253(17)30266-2

CrossRef - McGill MR, Jaeschke H. MicroRNAs as signaling mediators and biomarkers of drug- and chemical-induced liver injury. J Clin Med. 2015;4(5):1063-78. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm4051063

CrossRef - Bianchi ME, Agresti A. HMG proteins: dynamic players in gene regulation and differentiation. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2005;15(5):496-506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gde.2005.08.007

CrossRef - Leers MP, Kogen W, Bjorklund V, et al. Immunocytochemical detection and mapping of a cytokeratin 18 neo-epitope exposed during early apoptosis. J Pathol. 1999;187(5):567-72.

https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1096-9896(199904)187:5%3C567::aid-path288%3E3.0.co;2-j

CrossRef - Björnsson E, Olsson R. Outcome and prognostic markers in severe drug-induced liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;42(2):481-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.20800

CrossRef - Ghem C, Sarmento-Leite RE, de Quadros AS, et al. Serum bilirubin concentration in patients with an established coronary artery disease. Int Heart J. 2010;51(2):86-91. https://doi.org/10.1536/ihj.51.86

CrossRef - Antoine DJ, Dear JW, Lewis PS, et al. Mechanistic biomarkers provide early and sensitive detection of acetaminophen-induced acute liver injury at first presentation to hospital. Hepatology. 2013;58(2):777-87. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.26294

CrossRef - McGill MR, Cao M, Svetlov A, et al. Argininosuccinate synthetase as a plasma biomarker of liver injury after acetaminophen overdose in rodents and humans. Biomarkers. 2014;19(3):222-30. https://doi.org/10.3109/1354750x.2014.897757

CrossRef - Church RJ, Kullak-Ublick GA, Aubrecht J, et al. Candidate biomarkers for the diagnosis and prognosis of drug-induced liver injury: an international collaborative effort. Hepatology. 2018;67(5):2000-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29802

CrossRef - Mikus M, Drobin K, Gry M, et al. Elevated levels of circulating CDH5 and FABP1 in association with human drug-induced liver injury. Liver Int. 2017;37(1):132-40. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.13174

CrossRef - Qin S, Zhou Y, Gray L, et al. Identification of organ-enriched protein biomarkers of acute liver injury by targeted quantitative proteomics of blood in acetaminophen- and carbon-tetrachloride-treated mouse models and acetaminophen overdose patients. J Proteome Res. 2016;15(9):3724-40. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.13174

CrossRef - Ozer J, Ratner M, Shaw M, Bailey W, Schomaker S. The current state of serum biomarkers of hepatotoxicity. Toxicology. 2008;245(3):194-205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tox.2007.11.021

CrossRef - Lindblom P, Rafter I, Copley C, et al. Isoforms of alanine aminotransferases in human tissues and serum: differential tissue expression using novel antibodies. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;466(1):66-77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abb.2007.07.023

CrossRef - Foster GR, Goldin RD, Oliveira DB. Serum F protein: a new sensitive and specific test of hepatocellular damage. Clin Chim Acta. 1989;184(1):85-92. https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-8981(89)90259-3

CrossRef - Ashamiss F, Wierzbicki Z, Chrzanowska A, et al. Clinical significance of arginase after liver transplantation. Ann Transplant. 2004;9(3):58-60.

- Murayama H, Ikemoto M, Fukuda Y, Tsunekawa S, Nagata A. Advantage of serum type-I arginase and ornithine carbamoyl transferase in the evaluation of acute and chronic liver damage induced by thioacetamide in rats. Clin Chim Acta. 2007;375(1-2):63-8 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2006.06.018

CrossRef - Kohonen, P., Parkkinen, J., Willighagen, E. et al.A transcriptomics data-driven gene space accurately predicts liver cytopathology and drug-induced liver injury. Nat Commun.2017;8(1): 15932. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15932

CrossRef - Moreno-Torres M, Quintás G, Castell JV. The potential role of metabolomics in drug-induced liver injury (DILI) assessment. Metabolites. 2022;12(6):564. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo12060564

CrossRef - Yang X, Salminen WF, Schnackenberg LK. Current and emerging biomarkers of hepatotoxicity. Curr Biomark Find. 2012;(2):43-55. https://doi.org/10.2147/CBF.S27901

CrossRef

Abbreviations List

ALT: Alanine aminotransferase,

AST: Aspartate aminotransferase,

HMGB1: High mobility group box-1,

ALD: Alcohol-associated Liver Disease,

NAFLD: Non- alcoholic fatty liver disease,

MAFLD: Metabolic dysfunction associated fatty liver disease,

DILI: Drug-induced liver injury,

HILI: Herbal medicine–induced liver injury,

ALP: Alkaline phosphatase,

GGT: Gamma-gltutamyl transferase,

GLDH: Glutamate dehydrogenase,

mtDNA: Mitochondrial DNA,

PCR: Polymerase chain reaction,

GST: Glutathione‑S‑transferase,

MDH: Malate dehydrogenase,

NAD⁺ : Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (oxidized form),

NADH: Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (reduced form),

NASH: Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis,

MASH: Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis,

SMASH: Smoking-associated steatohepatitis,

ASH: alcoholic steatohepatitis

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.