Manuscript accepted on : 31-08-2025

Published online on: 24-09-2025

Plagiarism Check: Yes

Reviewed by: Dr. Vivek Anand

Second Review by: Dr. Nehia Hussein

Final Approval by: Dr. Ali Elshafei

Hemamala Selvaraj* , Balachandar Subbu

, Balachandar Subbu and Kiruthiga Periyannan

and Kiruthiga Periyannan

Department of Microbiology, Rathnavel Subramaniam (RVS) College of Arts and Science, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India

Corresponding Author E-mail:haemamala@gmail.com

ABSTRACT: Products derived from shrimp constitute 7.2 lakh tonnes of frozen shrimp exported during 2022–2023, positioning them as the largest contributors to India's total seafood exports in both quantity and value. This volume accounts for nearly 45% of the total exports for the specified period (MPEDA, 2023). In India, the organized shrimp processing sector generates a significant amount of waste, potentially representing 40–60% of the total weight of the shrimp. This substantial waste output can be transformed into a valuable biopolymer, chitosan, sourced from marine crustaceans’ exoskeletons, particularly from shrimp, through demineralization, deproteination, and deacetylation processes. The shell of the shrimp Fenneropenaeus indicus was harvested and processed to yield chitosan with a Degree of Deacetylation (DD) of 79%. Chitosan was subsequently treated with sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and monochloroacetic acid in various concentrations at multiple temperature levels and time intervals to determine the optimal formulation for producing Carboxy Methyl Chitosan (CMCS). The ideal conditions for CMCS production were identified as a concentration of 60% sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and 40% concentration of monochloroacetic acid (MCA) at 60°C for 2 hrs. The Degree of Substitution (DS) for CMCS exceeded 50% across all samples and was characterized using FTIR spectroscopy and solubility tests. The antibacterial properties of CS and CMCS are evaluated against Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, demonstrating sensitivity.

KEYWORDS: Chitosan (CS); Carboxy methyl chitosan (CMCS); Degree of deacetylation (DD); FTIR, Antibacterial activity; Shrimp

| Copy the following to cite this article: Selvaraj H, Subbu B, Periyannan K. Carboxymethyl Chitosan with High Degree of Substitution: Synthesis, Optimization, Characterization, and Antibacterial Activity. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(3). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Selvaraj H, Subbu B, Periyannan K. Carboxymethyl Chitosan with High Degree of Substitution: Synthesis, Optimization, Characterization, and Antibacterial Activity. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(3). Available from: https://bit.ly/4nEJXWG |

Introduction

Global research focuses on converting waste into valuable resources; in this regard, the significant waste discarded in marine environments can be transformed into a biopolymer utilized across multiple applications. One of these polymers is chitin, which can be found in the shells of marine crustaceans such as shrimp.1 The shrimp production industry disposes of 3. 8 million tons of waste worldwide every year.2 The primary source for large-scale production of chitin and its derivatives is the shell waste from crustaceans.3 Chitin is the second most common biopolymer following cellulose. Chitosan, a cationic polysaccharide derived from chitin, possesses numerous unique physical, chemical, and biological properties, which include physico-chemical characteristics like molecular weight, degree of acetylation (DA), and degree of crystallinity,4 as well as biological traits such as biocompatibility and biodegradability.5 Despite its many properties, chitosan is only soluble in acidic solutions, limiting some of its biomedical applications.6 Chitosan and its derivatives are renewable, non-toxic to human cells, and environmentally friendly.5 Chitosan finds extensive use in various biomedical applications, including anti-inflammatory treatments,7 drug delivery,8 wound dressings,9 antidiabetic measures,10 anticoagulant therapies, antibacterial applications, fat binding, haemostatic effects, and hypocholesterolemic benefits.11 The solubility of chitosan is achieved through depolymerization and chemical modifications.12 The reactive amino groups, both primary and secondary alcohols, can be chemically altered to change their properties. Chitosan undergoes chemical modifications such as quaternization, hydrophilization, phosphorylation, and carboxymethylation to enhance its water solubility. The derivatives that are water-soluble are mainly prepared via quaternization or by adding hydrophilic groups like hydroxypropyl, dihydroxyethyl, hydroxylamine, sulfate phosphate, carboxyl groups such as carboxymethyl, carboxyethyl, and carboxybutyl, or by grafting water-soluble polymers onto the macromolecular chain of chitosan.13 Any of the aforementioned methods can be employed to create various derivatives of chitosan. Among the other water-soluble derivatives, carboxymethyl chitosan (CMCS) has garnered considerable attention and has been extensively studied due to its easy synthesis, water solubility, ampholytic nature, and wide range of applications.5 CMCS is primarily utilized in biomedical fields, serving roles as a bactericide,14 in tissue engineering,8 as a blood anticoagulant,15 in wound dressings, as a moisture-retention agent, and for drug administration 16 and haemostatic material.17

The aim of this study is to extract chitin from the exoskeletons of marine crustaceans, which are regarded as waste in coastal regions, and transform it into chitosan (CS). The chitosan is insoluble in water at a neutral pH, so it is subsequently modified into a water-soluble biopolymer known as Carboxy Methyl Chitosan (CMCS), recognized for its beneficial properties in the pharmaceutical sector. During the conversion from CS to CMCS, various factors such as the acid-alkali ratio, alkalization time, and alkalization temperature are systematically altered to identify the optimal conditions for generating high-quality CMCS that is appropriate for pharmaceutical uses.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of chitosan

The shell of the Indian shrimp F. indicus was gathered and rinsed in boiling water to eliminate the adhered flesh and subsequently air-dried and then dried in an oven for 24 hours at 80° C.18 The desiccated samples were finely milled into powder using an electric blender and kept in an airtight container. For 30 minutes 20 g of the powder was treated with 1N HCl in the ratio (W/V) at 30±2°C. After that, it was rinsed under tap water until the pH of the processed sample turned neutral. Then for 2 hours the sample was deproteinized using 3.5 % NaOH in 1:10 (W/V) ratio at 75°C. The sample was washed further with tap water until its pH became neutral. The sample underwent treatment at 120°C for 3 hours with 60 % NaOH 1:10 (W/V) ratio, followed by a water wash, neutralization with tap water, and drying for 4 hours at 60°C.

Physical parameters

The physical parameters such as yield percentage, moisture content, solubility test, ash test, water binding, and fat binding capacity of the chitosan sample was analysed.

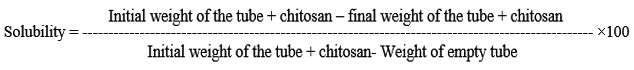

Solubility test

To evaluate the samples solubility test by dissolving 0.1 g of produced chitosan was dissolved in 10 ml of 1% acetic acid in triplicates in centrifuge tube of known weight 19. This was incubated in a shaker incubator at 25° C at 240 ×g for 30 min. The mixture was then centrifuged at 500×g for 10 min after being heated for 10 min in a boiling water bath and cooled to 25˚C. The supernatant was discarded and the undissolved particles washed in 25 ml of distilled water. The remaining particles were dried in an oven and the mass of the particle is weighed and the solubility was calculated using the formula 1

Determination of sulphated ash and inorganics in the sample

One gram of the sample was taken in a crucible that was weighed in an order to determine the inorganics in the sample in accordance with the Brazilian Pharmacopeia20. One millilitre of strong sulphuric acid added to wet the sample and then heated slowly until it charred. After cooling the sample, 1 ml of strong sulphuric acid was added to the sample in the crucible and heated at 600˚ C and kept there until the sample is completely ignited. The crucible was weighed after cooling in a desiccator. Until the constant weight gained, the cycle of heating and cooling repeated. The contents of sulphated ash are calculated as,

![]()

Where, W is the weight of the original test sample (before ashing)

W1, is the weight of the empty crucible (before ignition)

W2, weight of crucible and ash (after ignition)

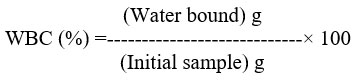

Water binding capacity (WBC)

In a centrifuge tube 10ml of distilled water combined with 0.5 g of produced chitosan and mixed thoroughly. After 30 min of intermittent shaking at room temperature the contents were centrifuged for 25 min at 3500×g. The supernatant was decanted, and the tube was weighed.21

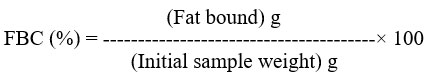

Fat binding capacity (FBC)

In a centrifuge tube, 10 ml of soy bean oil and 0.5 g of produced chitosan are combined and carefully mixed22. After 30 minutes of sporadic shaking (5 s every 10 min) at room temperature, the contents were centrifuged for 25 minutes at 3500 ×g. The tube was weighed after the supernatant was decanted. FBC was determined in this way:

Determination of the degree of deacetylation (DD)

After mixing 200 mg of KBr with 4 g of the sample, the mixture was shaped into pellets. At 25°C±2°C, pellets were scanned in the 400–4000 cm-1 spectral region. A Shimadzu spectrometer was used to record the infrared spectra at room temperature while utilizing the KBr. The formula was used to determine the chitosan’s degree of deacetylation (DD). 23

DD (%) = (A3450/A1655-0.38)÷1.33×100

Where,

A3450 represents the absorbance at 3450 cm-1

A1655 denotes the absorbance at 1655 cm-1,

0.38 and 1. 3 are constants.

Preparation and optimization of carboxy methyl chitosan

The preparation technique was slightly adjusted to determine the optimal concentration for the creation of CMCS, and the optimum concentration was chosen based on the FTIR spectrum and was selected for further investigation.

Treatment of chitosan with sodium hydroxide

A magnetic stirrer was used to mix 50 ml of isopropanol with 2g of chitosan for two hours at room temperature24. Sodium hydroxide was then added at 20%, 40%, and 60% aqueous NaOH, which was refluxed at 85° C every half an hour. This was followed by the addition of 100 ml of 60% aqueous mono chloroacetic acid in five equal steps over ten minutes. For an additional eight hours, the mixture was heated at 65° C while being stirred. In order to neutralize the reaction mixture, 4M HCL was added drop wise. The resulting CMCS was precipitated using methanol after that the undissolved residue was removed by filtering. After being filtered and rinsed with a 3:1 methanol/water ratio, the finished product was allowed to air dry. The ideal concentration of sodium hydroxide for the formation of CMCS will be selected for further treatment based on the results.

Treatment of chitosan with chloroacetic acid

Using a magnetic stirrer, 50 ml of isopropanol and 2g of chitosan were combined and allowed to sit at room temperature for two hours25. After that, at 85° C, the ideal sodium hydroxide concentration was added and refluxed every 30 minutes. One hundred millilitres of aqueous mono chloroacetic acid at 20%, 40%, and 60% were then added in five equal steps over ten minutes. For an additional eight hours, the mixture was heated at 65° C while being stirred. The reaction mixture was neutralized by incrementally adding 4M HCL. The mixture was allowed to cool and was filtered. The undissolved residue was removed by filtration, and the resulting CMCS was precipitated using methanol. The final product was filtered and washed with methanol and water in a 3:1 ratio and air-dried. Based on the findings, the optimal concentration of mono chloroacetic acid for CMCS production will be chosen for further processing.

Determination of optimum alkalization time

Using a magnetic stirrer, 50 ml of isopropanol and 2g of chitosan were mixed for two hours at room temperature 24. After that, the sodium hydroxide concentration was optimized and refluxed at 85° C for one, two, three, four, and six-hour intervals. Five equal parts of the optimal concentration of mono chloroacetic acid were then added over the course of ten minutes. The mixture was cooked for eight hours at 65° C while being stirred. After being progressively added to the reaction mixture, 4M HCL was used to neutralize it. Before being filtered, the mixture was given time to cool. After filtering out the undissolved residue, methanol was used to precipitate the resultant CMCS. The product was filtered, rinsed with a 3:1 solution of methanol and water, and allowed to air dry. The duration of the reaction for the production of CMCS in successive treatments was determined by the results, which also determined the optimal alkalization time.

Determination of alkalization Temperature

For two hours, 50 ml of isopropanol and 2g of chitosan were mixed in a magnetic stirrer at room temperature25. The sodium hydroxide concentration was then added and refluxed at 40°C, 50°C, 60°C, and 70°C for the optimal amount of time. After that, five equal portions of the optimal concentration of mono chloroacetic acid were administered over the course of ten minutes. For eight hours, the mixture was heated at 65° C while being stirred. 4M HCL was progressively added to the reaction mixture in order to neutralize it. After cooling, the mixture was filtered. After filtering out the undissolved residue, methanol was used to precipitate the resulting CMCS. After filtering, the product was rinsed with a 3:1 solution of methanol and water and left to air dry. According to the findings, the ideal alkalization temperature was chosen to be the alkalization reaction temperature for the production of CMCS.

Physical Characterisation

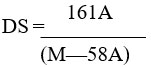

Determination of degree of substitution (DS)

The titrimetric approach was used to determine the CMCS’s degree of substitution (DS).25 20 millilitres of distilled water were used to dissolve a 0.10 gram sample. Standard 0.10 M hydrochloric acid was added to the solutions to bring their pH down to less than 2. After titration of the solutions with 0.050 M standard aqueous NaOH, the pH readings were simultaneously recorded while being constantly stirred until it reaches 11.5.

Where,

The volume of NaOH solution recorded between the two inflection points, C, is equal to A=V NaOH × C NaOH. m is the mass of the samples, and NaOH is the molarity of the aqueous NaOH (0.050 mol/L); the molecular weights of the carboxymethyl group and glucosamine are 58 and 161, respectively.

Characterization using FTIR spectra

The functional groups in CS and CMCS samples were examined by Fourier infrared spectrophotometer (JASCO FT/IR-4600 type A Serial Number E168661786 Accessory ATR PRO ONE) in the 400–4000 cm-1 spectral region26

Solubility tests

The materials’ water solubility was evaluated by visual inspection at room temperature. Using a vortex mixer, 20 mg of the material was first dissolved in 100 ml of distilled water and well mixed. Following the achievement of a clear solution, 10 mg was added repeatedly until precipitation happened. The solubility limit level was defined as the total amount of product added.27

Chitosan’s and carboxymethyl chitosan’s antimicrobial properties

The concentrations of chitosan and carboxymethyl chitosan were made as 100 mg, 15 mg, 20 mg, and 30 mg. In nutrient broth, fresh cultures of S.aureus and P. aeruginosa were created, and the inoculum was adjusted to a predetermined concentration, typically between 1 and 108 CFU/mL. The test organism was dispersed over the agar’s surface. 20 µL of each concentration was added to the properly labeled plates for the test species, such as P.aeruginosa and S. aureus, after wells were made using a gel puncture. The test control was streptomycin sulphate (0.1%). For 18 to 24 hours, the plates were incubated at 37°C. The diameter of the inhibition zone was used to measure the antibacterial activity of CS and CMCS.28

Results

Preparation of chitosan

The yield of extracted chitosan was determined to be 36%, with a moisture content of 4.4%, ash content of 1.9%, pH of 7. 3 and the chitosan were observed to be creamy white flakes (Fig. 1). The WBC of the sample was measured at 654 and the FBC was measured at 400. The degree of deacetylation was calculated to be 79. 4%. Chitosan exhibited solubility in 1% acetic acid and was insoluble in water. The chitosan that was obtained has a degree of deacetylation (DD) of 79%. A DD above 70 % or close to 80 % is considered to be high quality chitosan.

|

Figure 1: ChitosanClick here to view Figure |

|

Figure 2: Carboxy methyl chitosan Click here to view Figure |

Preparation and optimization of carboxy methyl chitosan

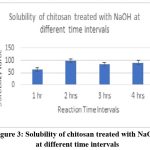

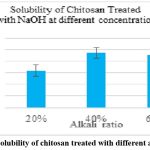

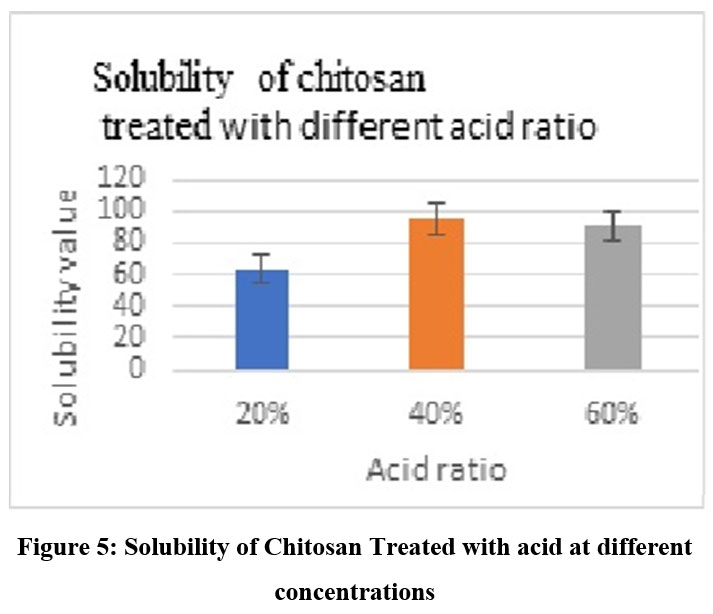

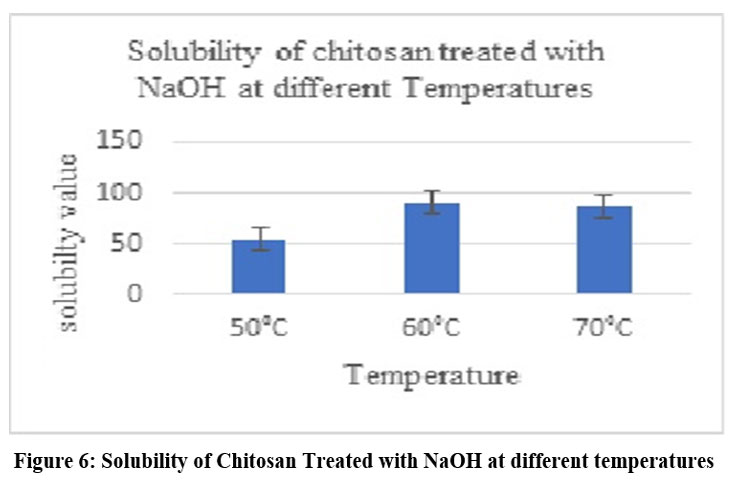

Chitosan was converted to carboxymethyl chitosan, and in certain cases, the samples’ water solubility was found to be partial, while in other cases, it was very high. The degree of CMCS substitution was 50%, and the CMCS was seen as delicate white flakes (Fig. 2). In comparison to other samples, the sample treated with 60% NaOH (Fig. 4), 60% C (Fig. 5), 2 hours of alkalization(Fig. 3), and 40% acid(Fig. 6) was found to be highly soluble this might be because the FTIR spectra (Fig. 8–11) indicated the existence of hydrophilic groups in these samples. According to particular criteria, some samples exhibited just partial water solubility, while others showed noticeably great solubility. All samples’ solubility values were analysed using means plus or minus standard deviation, and the results were displayed visually (Fig. 3-6).

|

Figure 3: Solubility of chitosan treated with NaOH at different time intervalsClick here to view Figure |

|

Figure 4: Solubility of chitosan treated with different alkali ratiosClick here to view Figure |

|

Figure 5: Solubility of Chitosan Treated with acid at different concentrationsClick here to view Figure |

|

Figure 6: Solubility of Chitosan Treated with NaOH at different temperaturesClick here to view Figure |

Modification of chitosan to carboxymethyl chitosan

FTIR Spectrum

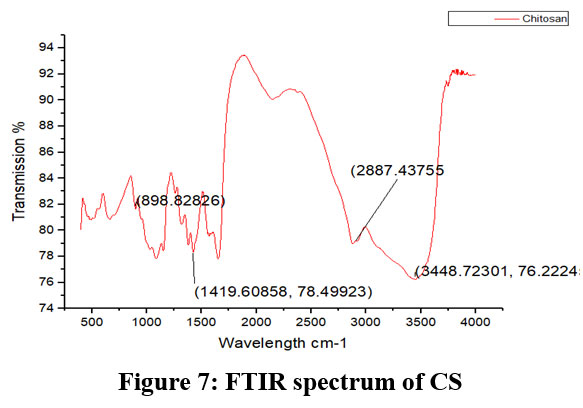

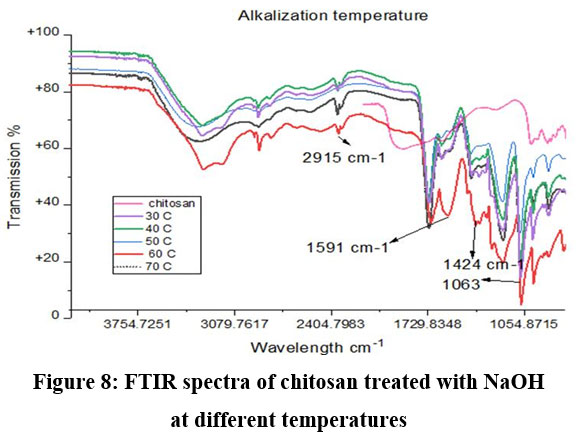

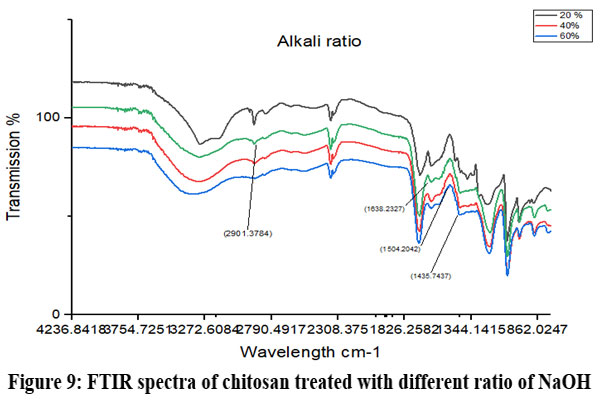

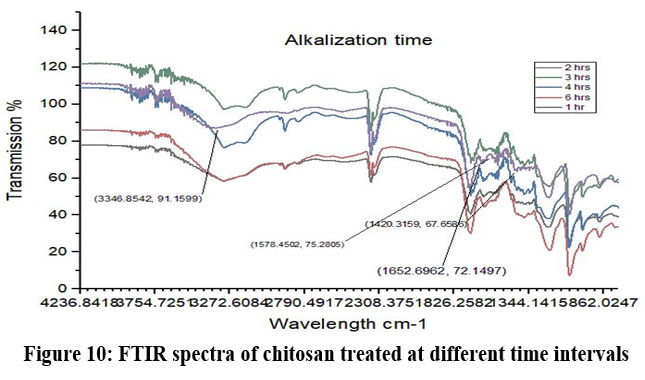

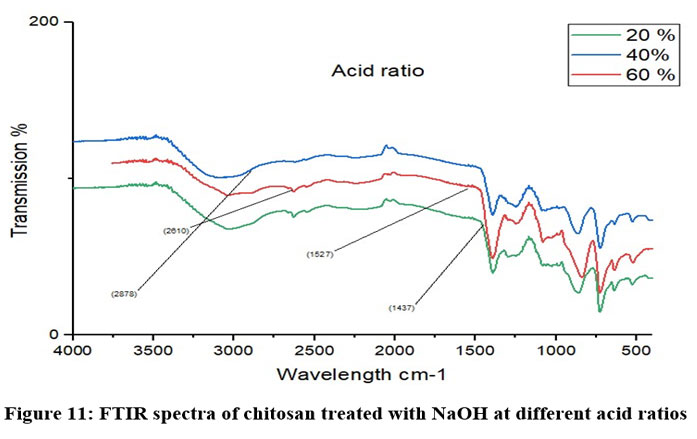

Chitosan’s characteristic spectra were found at 3450 cm-1, 2877 cm-1, 1425 cm-1, 1087 cm-1, and 898 cm-1, respectively (Fig.7). These spectra showed the existence of ring stretching, amino stretching, CH stretching, Amide C=O stretching, and CO stretching (Fig. 7). The alkali ratio, the alkalization timing, the acid ratio, and the alkalization temperature are the four crucial factors in the conversion of chitosan to carboxymethyl chitosan CMCS. The sample treated at 60°C showed hydroxyl stretching at 3312 cm-1, C-H stretching at 2924 cm-1, C=O stretching (carboxyl group) at 1712 cm-1, and asymmetric COO- stretching at 1591 cm-1 with respect to the alkalization temperature (Fig.8). The carboxymethyl chitosan is represented by these distinctive peaks. It was found that the ideal temperature for converting CS to CMCS was 60°C out of all the temperature ranges. When it came to alkali concentration, chitosan CS treated with 60% sodium hydroxide showed C-H stretching in the alkanes, which is pertinent to the chitosan backbone at 2915 cm-1, and C=O stretching in the carbonyl-containing functional group, which is equivalent to the carboxyl group in the carboxymethyl modification of chitosan at 1713 cm-1.29 The major carboxymethyl peaks are aligned with the N-H bending and COO- stretching in carboxymethyl chitosan at 1634 cm-1 and the C-O stretching close to 1224 cm-1. O-H, N-H, C=O, and COO lengths are among its primary functional groups (Fig.9). Peaks showing C-H stretching at 2916 cm-1, C=O stretching at 1719 cm-1, asymmetric COO-stretching at 1592 cm-1, symmetric COO stretching at 1403 cm-1, and N-H bending at 1622 cm-1 were seen during the alkalization stage (Fig.10). The infrared spectrum shows carboxymethyl chitosan from these peaks. The ideal period was found to be two hours, during which the carboxymethyl chitosan functional peaks were visible. The 40% concentration showed the carboxyl group at 1724 cm-1 and symmetric and asymmetric COO- stretching at 1557 cm-1 and 1421 cm-1, respectively, in relation to the chloroacetic acid ratio (Fig.11).

|

Figure 7: FTIR spectrum of CSClick here to view Figure |

|

Figure 8: FTIR spectra of chitosan treated with NaOH at different temperaturesClick here to view Figure |

|

Figure 9: FTIR spectra of chitosan treated with different ratio of NaOHClick here to view Figure |

|

Figure 10: FTIR spectra of chitosan treated at different time intervalsClick here to view Figure |

|

Figure 11: FTIR spectra of chitosan treated with NaOH at different acid ratiosClick here to view Figure |

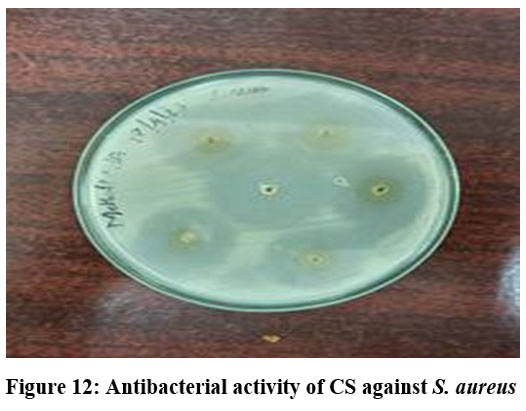

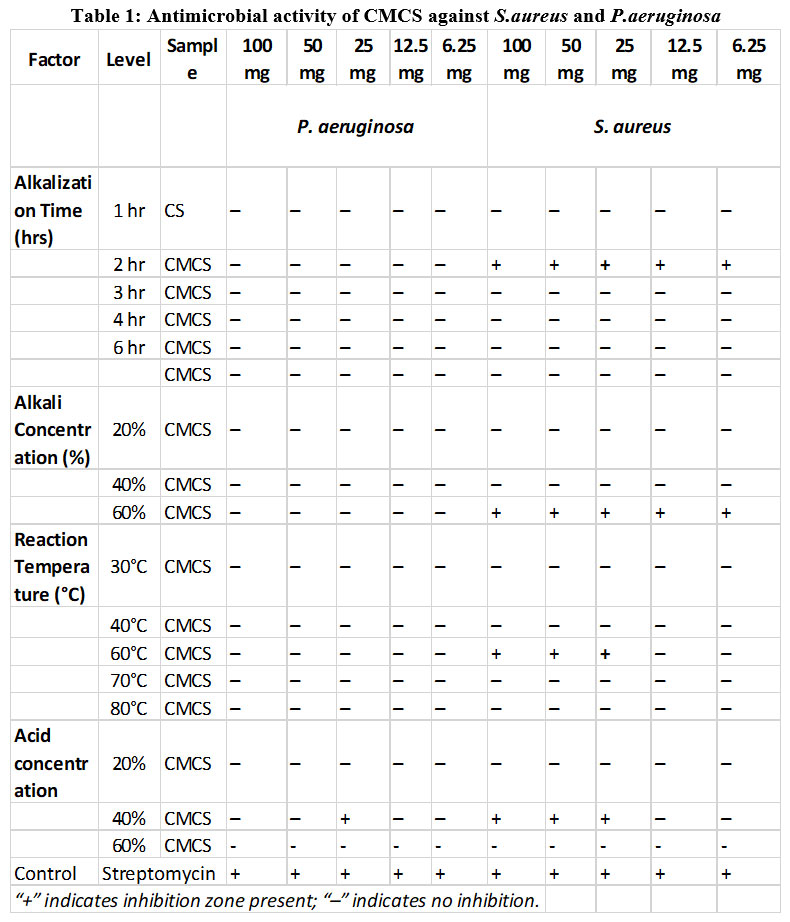

Antibacterial Activity

At a dosage of 25 mg, the antibacterial activity of CS was evaluated against S. aureus and P. aeruginosa. The findings demonstrated that compared to the gram-negative organism, the gram-positive organism had a wider zone of inhibition (Fig.12). Both species demonstrated resistance to the samples when CS and CMCS concentrations increased. There is great potential for the use of carboxymethyl chitosan in medicine because it is an amphoteric, water-soluble chitosan derivative that is nontoxic, biocompatible, and biodegradable. These features result from the increased surface positive charge.30 Gram-positive bacteria responded better to CS than CMCS, while gram-negative bacteria displayed less bactericidal effect from CMCS (Table:1). The greatest inhibition for CMCS was found at a sample concentration of 25 mg, specifically at a reaction temperature of 60°C, an alkalization period of two hours, and an alkali concentration of 40–60%. Reduced or no antibacterial activity was seen at lower concentrations and at less-than-ideal processing conditions.

|

Figure 12: Antibacterial activity of CS against S. aureus Click here to view Figure |

|

Table 1: Antimicrobial activity of CMCS against S.aureus and P.aeruginosaClick here to view Figure |

Discussion

Chitosan’s (CS) molecular weight and suitability for biological systems are related to how much of it has been deacetylated. Chitosan’s solubility, biological activity, and interactions with biological membranes are all enhanced when its DD is greater than 75%. Increased DD levels increase the concentration of amino groups, improving their antibacterial and water-soluble qualities as well as their effectiveness in drug delivery systems. 31 Additionally, the molecular weight is important. Low molecular weight chitosan is suitable for biomedical applications since it is simpler to handle and dissolve. Greater viscosity is a benefit of using high molecular weight chitosan for making films and hydrogels. 32 Depending on the parent material, extraction technique, and degree of purity, chitosan can have an off-white to light brown color. Even after processing, the light brown color of chitosan made from crab shells is influenced by leftover minerals, proteins, and pigments. Its appearance is also influenced by the molecular weight and degree of deacetylation. More purification produces lighter-colored chitosan, which is chitosan with a higher DD. 33 In certain samples, the degree of substitution was found to be higher than 50%, while in others, it was lower. The goal of carboxymethyl chitosan’s (CMCS) degree of substitution has been to enhance its antibacterial, antioxidant, and biological properties. The average number of substituted hydroxyl (-OH) or amino (-NH₂) groups for each glucosamine unit in the chitosan structure is known as the degree of substitution (DS). This measurement is crucial since it affects CMCS’s solubility, viscosity, and biological activity. On average, 50% of the chitosan molecule’s reactive sites (hydroxyl and amino groups) have been substituted out for carboxymethyl groups, according to a 50% substitution prediction. The length of the reaction, temperature, pH, and concentrations of the reagents (NaOH and TCA) all affect this partial substitution of carboxymethyl chitosan. The degree of substitution and the manufacturing method affected how carboxymethyl chitosan looked. 33 Depending on how it is processed and dried, carboxymethyl chitosan can have a granular or fibrous texture.34 The degree of substitution was correlated with the samples’ solubility; the more substitution levels, the more soluble the samples were in water. The chitosan molecule’s water solubility is influenced by the extent to which its carboxymethyl groups have been substituted.

The FTIR spectrum of carboxymethyl chitosan revealed various functional groups; significant peaks include the OH stretching at 3400 cm-1 and the N-H stretching (amine) at 1590-1650 cm-1, indicating residual amine groups. The C=O and COO- stretching observed at 1400-1560 cm-1 is associated with carboxyl groups resulting from carboxymethylation the C-O-C ether bonds at 1050-1150 cm-1 indicate ether linkages arising from modification.35 The antibacterial effects of chitosan and its derivatives are influenced by their physicochemical characteristics, which include molecular weight, hydrophilicity, hydrophobicity, water solubility, positive charge density, degree of deacetylation, concentration, chelating capacity, and pH.

The degree of deacetylation; greater deacetylation results correlate with CS antimicrobial activity, and the higher the level of deacetylation, the stronger the antibacterial activity.6 Xiao et al., investigated the antimicrobial properties of O-carboxy methyl derivatives of chitosan against Bacillus, E. coli, and S. aureus. Gram-positive bacteria were more susceptible to O-CMCS’s bactericidal effects than gram-negative ones. This shows how chitosan affects S. aureus. Because of differences in cell wall construction, the antibacterial impact in this study was different from that seen with gram-negative bacteria. The thick, dense cell wall of gram-positive bacteria is made up of 15–40 interwoven peptidoglycan layers. Free NH₃ groups that are positively charged adhere to the cell wall’s constituent parts, creating holes in the wall that allow a substantial leakage of cell components and ultimately induce cell death. Chitosan has antibacterial properties because it can damage the membranes of bacteria and fungi, among other microbes. Chitosan is efficient against a variety of pathogens, such as bacteria, yeasts, molds, and viruses, according to studies on its antimicrobial properties. 36 E. coli, S. aureus, Salmonella, C. albicans, and A. niger are some of the pathogenic microorganisms that chitosan has been demonstrated to be effective against. Higher positive charge chitosan compounds have less antibacterial action. Chitosan derivatives with higher positive charges show reduced antibacterial activity. This may imply that elevated cationic charge alone does not assure superior antibacterial activity when compared to that of modified versions. Chitosan was observed to be equally active against S. aureus at pH 5.5 and 7.2 (MIC = 256 μg/mL). Chitosan is only active in the acidic medium; however, it was reported that the limited activity above pH 6 may originate from the poor solubility above pH 6.37 Whereas Carboxymethyl chitosan is an amphoteric polymer, meaning it can carry both positive and negative charges depending on the pH of the environment. Farag et al.’s38 study revealed that the nanogel blended with carboxymethyl chitosan and polyvinyl alcohol has greater activity in a gram-negative organism than a gram-positive organism. In general, E. coli was more susceptible to the antibacterial properties of the studied nanogels than S. aureus. Gram-negative bacteria are surrounded by a thin peptidoglycan cell wall, which itself is surrounded by an outer membrane containing lipopolysaccharide. Gram-positive bacteria lack an outer membrane but are surrounded by layers of peptidoglycan many times thicker than is found in the Gram-negatives39. E. coli and P. aeruginosa, both Gram-negative bacteria, have cell walls with a similar overall structure but differ in some key components and their roles in antibiotic resistance. Both possess a thin peptidoglycan layer and an outer membrane. However, the extent of lipoprotein presence and the specific enzymes involved in cell wall synthesis and recycling can differ, impacting their susceptibility to certain antibiotics40

Because the amino groups in chitosan are protonated at low pH (acidic conditions), the dominant charge will be positive; the carboxyl groups introduced by the carboxymethylation process will be deprotonated at high pH (alkaline conditions). Because of this pH-dependent charge behavior, CMC is a useful material for a variety of applications, such as drug delivery, tissue engineering, and environmental remediation.41

Conclusion

This study concentrated on converting chitin found in shrimp waste from the exoskeletons of marine crustaceans into chitosan and subsequently transforming it into its derivative, CMCS, by utilizing different concentrations of alkali and specific temperatures for alkalisation, along with alkalisation duration and acid ratio. The ideal concentration of the alkali was determined to be 60% at a 60°C temperature for 2hrs, with 40 % acid also being identified as the optimal concentration, temperature, and duration. These samples exhibit good solubility, which is fundamental in pharmaceutical applications. Regarding antibacterial activity, when compared to the CS sample, CMCS is less effective towards both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. and to enhance the efficacy of CMCS against bacteria, additional compounds can be added.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the DST FIST lab of RVS CAS for providing help in the instrumental analysis.

Funding Sources

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

This statement does not apply to this article.

Ethics Statement

This research did not involve human participants, animal subjects, or any material that requires ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not involve human participants, and therefore, informed consent was not required.

Clinical Trial Registration

This research does not involve any clinical trials

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

Not Applicable

Author contributions

Hemamala Selvaraj: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft.

Balachandar Subbu: Supervision.

Kiruthiga Periyannan: Visualization.

References

- Tzeng HP, Liu SH, Chiang MT. Antidiabetic Properties of Chitosan and Its derivatives. Mar Drugs. 2022;20(12):784. https://doi.org/10.3390/md20120784

CrossRef - Mawazi SM, Kumar M, Ahmad N, Ge Y, Mahmood S. Recent Applications of Chitosan and Its Derivatives in Antibacterial, Anticancer, Wound Healing, and Tissue Engineering Fields. Polym.J.2024;16(10):1351. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16101351

CrossRef - Casadidio C, Peregrina DV, Gigliobianco MR, Deng S, Censi R, Di Martino P.Chitin and Chitosans: Characteristics, Eco-Friendly Processes, and Applications in Cosmetic Science. Mar Drugs. 2019;17(6):369.https://doi.org/doi:10.3390/md17060369

CrossRef - Aranaz I, Alcántara AR, Civera MC, Arias C, Elorza B, Heras Caballero A, Acosta N. Chitosan: An Overview of Its Properties and Applications. Polymers. 2021; 13(19):3256. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13193256.

CrossRef - Parmaksız, S., & Şenel, S. Carboxymethyl chitosan for drug and vaccine delivery: an overview. In Advances in polymer science. 2023; 225–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/12_2023_156

CrossRef - Wang L, Guo R, Liang X, Ji Y, Zhang J, Gai G, Guo Z. Preparation and Antioxidant Activity of New Carboxymethyl Chitosan Derivatives Bearing Quinoline Groups. Mar Drugs. 2023; 21(12):606. https://doi.org/10.3390/md21120606

CrossRef - Ayaz F, Demir D, Bölgen N. Differential anti-inflammatory properties of chitosan-based cryogel scaffolds depending on chitosan/gelatin ratio. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2021;49(1):682-690. https://doi.org/10.1080/21691401.2021.2012184

CrossRef - Zargar, V., Asghari, M. and Dashti, A. A Review on Chitin and Chitosan Polymers: Structure, Chemistry, Solubility, Derivatives, and Applications. ChemBioEng Reviews. 2015;2,204-226.

https://doi.org/10.1002/cben.201400025

CrossRef - Yousefian F, Hesari R, Jensen T, et al. Antimicrobial Wound Dressings: A Concise Review for Clinicians. Antibiotics (Basel). 2023;12(9):1434. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12091434

CrossRef - Thanakkasaranee S, Jantanasakulwong K, Phimolsiripol Y, et al. High Substitution Synthesis of Carboxymethyl Chitosan for Properties Improvement of Carboxymethyl Chitosan Films Depending on Particle Sizes. Mol. 2021; 26(19):6013. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26196013

CrossRef - Shahidi F, Abuzaytoun R. Chitin, chitosan, and co-products: chemistry, production, applications, and health effects. Adv Food Nutr Res. 2005;49:93-135. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1043-4526(05)49003-8

CrossRef - Thambiliyagodage C, Jayanetti M, Mendis A, Ekanayake G, Liyanaarachchi H, Vigneswaran S. Recent Advances in Chitosan-Based Applications—A Review. J. Mater. 2023; 16(5):2073. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16052073

CrossRef - Nirmal, N.P., Santivarangkna, C., Rajput, M.S., Benjakul, S. Trends in Shrimp Processing Waste Utilization: An Industrial Prospective. Trends Food Sci. Technol., 2020; 103: 20–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2020.07.001

CrossRef - Gao, H., Zhong, Z., Xia, H., Hu, Q., Ye, Q., Wang, Y., and Zhang, L Construction of cellulose nanofibers/quaternized chitin/organic rectorite composites and their application as wound dressing materials. Biomaterials Science. 2019; 7: 2571-2581. Biomater. Sci.,http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/C9BM00 288J

CrossRef - Kruczkowska W, Kłosiński KK, Grabowska KH, et al. Medical Applications and Cellular Mechanisms of Action of Carboxymethyl Chitosan Hydrogels. Mol. 2024;29(18):4360. https://doi.org/10.3390/ molecules29184360

CrossRef - He, Yuanmeng , Guo, Shen et al. Facile preparation of antibacterial hydrogel with multi-functions based on carboxymethyl chitosan and oligomeric procyanidin. RSC Advances. 2022;12. 20897-20905. https://doi.org/10.1039/D2RA04049B

CrossRef - Chen, Q., Qi, Y., Jiang, Y., Quan, W., Luo, H., Wu, K Progress in research of chitosan chemical modification technologies and their applications. Mar Drugs., 2022; 20(8):536. https://doi.org/ 10.3390/md20080536

CrossRef - Varun TK, Senani S, Jayapal N, Chikkerur J, Roy S, Tekulapally VB, Gautam M, Kumar N. Extraction of chitosan and its oligomers from shrimp shell waste, their characterization and antimicrobial effect. Veterinary World, 2017 10(2): 170-175. https://doi.org/10.14202/vetworld.2017.170-175

CrossRef - Rinaudo, M.; Pavlov, G.; Desbrières, J. Influence of acetic acid concentration on the solubilization of chitosan. Polymer 1999, 40, 7029–7032. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0032-3861(99)00056-7

CrossRef - BRASIL. Ministério da Saúde. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. Farmacopeia Brasileira, 6. ed., v.1. Brasília: Anvisa, 2019. Monografia: Chitosan, p. 150–153.

- Wang, J., Chen, L., & Liu, C. Water-binding capacity of chitosan and its effect on functional properties of emulsions. Food Hydrocolloids. 2014; 38 151–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.foodhyd.2013.12.001

CrossRef - El-Araby A, Janati W, Ullah R, Ercisli S, Errachidi F. Chitosan, chitosan derivatives, and chitosan-based nanocomposites: eco-friendly materials for advanced applications (a review). Front Chem. 2024; 11:1327426. https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2023.1327426

CrossRef - Roberts, George A.F., Domszy, Julian G. Determination of the viscometric constants for chitosan. Int.J.Biol. Macromol.1982; 4: 374-377 https://doi.org/10.1016/0141-8130(82)90074-5

CrossRef - Subhash S Vaghani, Madhabhai M Patel, Satish C.S, Kandarp M Patel and Jivani N P. Synthesis and characterization of carboxymethyl chitosan hydrogel: Application as site specific delivery for lercanidipine hydrochloride. Bull. Mater. Sci., 2012 35 (7), pp. 1133–1142. https://doi/10.1007/ s12034-012-0413-4

CrossRef - Ge HC, Luo DK. Preparation of carboxymethyl chitosan in aqueous solution under microwave irradiation. Carbohydr Res. 2005;340(7):1351-1356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carres.2005.02.025

CrossRef - Domínguez, R. Extraction and Characterization of Chitosan from Shrimp Shells. Ph.D. Thesis, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 2003. https://doi.org/10.31390/ gradschool_ disstheses.432

CrossRef - Zhou, Y.; Zhai, Z.; Yao, Y.; Stant, J. C.; Landrum, S. L.; Bortner, M. J.; Frazier, C. E.; Edgar, K. J. Reductive Amination of Oxidized Hydroxypropyl Cellulose with ω-Amino Carboxymethyl Chitosan: Synthesis and Characterization. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2023.121699

CrossRef - Oluwasina, O.O.; Fagbenro, N.O.; Adegbola, E.G.; Ogunleye, P.A. Synthesis, Characterization and Antibacterial Evaluation of Carboxymethyl Chitosan–Zn Complexes. Cogent Chem. 2017, 3, 1294470. https://doi.org/10.1080/23312009.2017.1294470

CrossRef - Carrasco-Sandoval J, Aranda M, Henríquez-Aedo K, Fernández M, López-Rubio A, Fabra MJ. Impact of molecular weight and deacetylation degree of chitosan on the bioaccessibility of quercetin encapsulated in alginate/chitosan-coated zein nanoparticles. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;242(Pt 2):124876. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.124876

CrossRef - Zhong Q-K, Wu Z-Y, Qin Y-Q, Hu Z, Li S-D, Yang Z-M, Li P-W. Preparation and Properties of Carboxymethyl Chitosan/Alginate/Tranexamic Acid Composite Films. Membranes. 2019; 9(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes9010011

CrossRef - Lusine R. Harutyunyan, Elena V. Lasareva R. Chitosan and its Derivatives: A Step Towards Green Chemistry. Biointerface research App Chem., 2023;13: 578. https://doi.org/10.33263/BRIAC136.578

CrossRef - Fatullayeva S, Tagiyev D, Zeynalov N, et al. Recent advances of chitosan-based polymers in biomedical applications and environmental protection. J Polym Res. 2022;29(259). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10965-022-03121-3

CrossRef - Wang L, Guo R, Liang X, et al. Preparation and antioxidant activity of new carboxymethyl chitosan derivatives bearing quinoline groups. Mar Drugs. 2023;21(10): 606. https://doi.org/10.3390/ md21100606

CrossRef - Yan D, Li Y, Liu Y, et al. Antimicrobial properties of chitosan and chitosan derivatives in the treatment of enteric infections. Molecules. 2021;26(23):7136. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26237136

CrossRef - Islam M, Islam R, Hassan SM, et al. Carboxymethyl chitin and chitosan derivatives: Synthesis, characterization and antibacterial activity. Carbohydr Polym Technol Appl. 2023;5:100283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carpta.2023.100283

CrossRef - Xiao B, Wan Y, Zhao M, Liu Y, Zhang S. Preparation and characterization of antimicrobial chitosan-N-arginine with different degrees of substitution. Carbohydr Polym. 2011;83(1):144–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.07.018

CrossRef - Zhou X, Zhou Q, Chen Q, et al. Carboxymethyl chitosan/tannic acid hydrogel with antibacterial, hemostasis, and antioxidant properties promoting skin wound repair. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2023;9(1):437–448. doi: https://doi.org/10.1021/acsbiomaterials.2c00997

CrossRef - Farag, R.K.; Mohamed, R.R. Synthesis and Characterization of Carboxymethyl Chitosan Nanogels for Swelling Studies and Antimicrobial Activity. Molecules2013, 18, 190-203. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules18010190

CrossRef - Silhavy, T. J., Kahne, D., & Walker, S. (2010). The bacterial cell envelope. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology, 2(5), a000414. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a000414

CrossRef - Dhar S, Kumari H, Balasubramanian D, Mathee K. Cell-wall recycling and synthesis in Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa – their role in the development of resistance. J Med Microbiol. 2018 Jan;67(1):1-21. doi: https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.000636

CrossRef - Wang W, Huang WC, He Y, Zhang Y, Mao X. Chitosan-Based Charge-Controllable Supramolecular Carrier for Universal Immobilization of Enzymes with Different Isoelectric Points.J. Agric. Food Chem 202472(42), 23458-23464.https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.4c07748

CrossRef

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.