Manuscript accepted on : 13-09-2025

Published online on: 24-09-2025

Plagiarism Check: Yes

Reviewed by: Dr. Ana Golez

Second Review by: Dr. Seyedeh Maryam Mousavi and Dr. Aisha Belal

and Dr. Aisha Belal

Final Approval by: Dr. Wagih Ghannam

Patrícia Maria Rocha , Carlos Eduardo de Araújo Padilha

, Carlos Eduardo de Araújo Padilha and Everaldo Silvino dos Santos*

and Everaldo Silvino dos Santos*

Department of Chemical Engineering, Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, Brazil

Corresponding Author E-mail: everaldo.santos@ufrn.br

ABSTRACT: Biosurfactants have potential applications in environmental sectors, as well as in the pharmaceutical, food, and other industries. Among the various classes of biosurfactants, lipopeptides, particularly surfactin and iturin, stand out. In the present study, the kinetic parameters related to the synthesis of surfactin and iturin were evaluated, along with the characterization of these biosurfactants produced by Bacillus subtilis UFPEDA 438. Additionally, extraction assays were conducted using a range of organic solvents (n-hexane, n-octanol, and chloroform-methanol 2:1, v/v), both with and without the addition of di-(2-ethylhexyl) phosphoric acid (D2EHPA). Maximum concentrations of surfactin and iturin were reached at 24 hours, corresponding to 187.01 ± 0.37 mg/L and 10.80 ± 1.03 mg/L, respectively. The lipopeptides exhibited good stability across a wide range of temperatures (20 to 100°C) and pH values from 6 to 9, and a critical micelle concentration (CMC) of 18.70 mg/L. The addition of the complexing agent D2EHPA, in combination with n-octanol (76.36%) and n-hexane (72.96%), improved the recovery efficiency of iturin. Regarding surfactin, n-octanol alone provided the highest recovery rate, reaching 72.22%.

KEYWORDS: Biosurfactants; D2EHPA; Iturin; Liquid-liquid extraction; Surfactin

| Copy the following to cite this article: Rocha P. M, Padilha C. E. D. A, Santos E. S. D. Lipopeptides Produced by Bacillus subtilis UFPEDA 438 using Sugarcane Molasses as a Carbon and Energy Source. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(3). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Rocha P. M, Padilha C. E. D. A, Santos E. S. D. Lipopeptides Produced by Bacillus subtilis UFPEDA 438 using Sugarcane Molasses as a Carbon and Energy Source. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(3). Available from: https://bit.ly/4nLSaYX |

Introduction

Biosurfactants are biological molecules that exhibit particularly high surface activity. They offer several advantages over synthetic surfactants, including high activity under extreme conditions (temperature, pH, salinity), low toxicity, and high biodegradability. These characteristics make them especially suitable for environmental applications such as bioremediation and enhanced oil recovery.1,2 Furthermore, biosurfactants are considered promising candidates to replace synthetic surfactants, especially in the food, pharmaceutical, cosmetic, healthcare, and industrial cleaning sectors, as well as in environmental applications.3-6

Surfactin and iturin are biosurfactants that belong to the family of cyclic lipopeptides, mostly isolated from Bacillus spp. Strains.7,8 Each lipopeptide family comprises several homologues, which vary in the amino acid sequence of the peptide moiety or the length of the fatty acid chain.9 Typically, strains are capable of synthesizing multiple isoforms of lipopeptides.10,11 These structural variations result in distinct functional and surfactant properties.

Regarding their functional properties, each lipopeptide family exhibits specific bioactivities. For example, surfactin is known for its antibacterial, antiviral, and antitumor activities, whereas iturins are reported to possess antifungal properties.11-13

For many biotechnological products, the downstream processing stage accounts for up to 60% of the total production cost, representing a major challenge for commercial applications.9 A major bottleneck in surfactin commercialization is its extraction and purification from complex fermentation broths. Preparative-scale separation of biosurfactants typically involves multiple steps, including precipitation, extraction with organic solvents, and chromatographic adsorption.14

Solvent extraction is commonly employed as an intermediate step in the recovery of bioproducts, facilitating their concentration and purification.15 Various organic solvents such as ethanol, ethyl acetate, butanol, methanol, acetone, n-hexane, chloroform, and dichloromethane can be used in this technique, either individually or in combination.14,16 However, researchers have been exploring new solvent systems to enhance the extraction efficiency of different types of biomolecules.

Given this context, the present study aimed to investigate the production of surfactin and iturin by Bacillus subtilis UFPEDA 438 grown in sugarcane molasses, as well as to evaluate the cultivation kinetics and characterize the functional properties of the biosurfactants. In addition, extractions were performed using different organic solvents (n-hexane, n-octanol, and chloroform–methanol 2:1, v/v). The effect of adding the extractant di-(2-ethylhexyl) phosphoric acid (D2EHPA) on the efficiency of the extraction process was also evaluated. To the best of our knowledge, the use of D2EHPA for lipopeptide recovery remains unexplored in literature.

Materials and Methods

Substrate

The sugarcane molasses used in this study was supplied by Usina Vale Verde, located in the municipality of Ceará-Mirim, state of Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil. Storage was carried out in a plastic container at -18°C.

Microorganism and maintenance medium

The Bacillus subtilis UFPEDA 438 strain was provided by the Department of Antibiotics at the Federal University of Pernambuco, Brazil. Cultures were maintained at 4°C on Plate Count Agar (PCA), and subculturing was performed every 60 days.

Inoculum preparation

Inoculum was prepared in a 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask containing 100 mL of culture medium. The medium was composed of 4.0% (w/v) sugarcane molasses, 1.0 g/L (NH₄)₂SO₄, and 0.1% (v/v) of a stock salt solution (0.3 g/L MnSO₄·H₂O, 0.1 g/L FeSO₄·7H₂O, 0.1 g/L EDTA, 0.1 g/L CoCl₂·6H₂O, 0.1 g/L ZnSO₄·7H₂O, and 0.1 g/L CaCl₂). The medium was previously adjusted to pH 7.0 using a 2.0 M NaOH solution. Cells from the maintenance medium were aseptically transferred into the flask and incubated on a shaker (Tecnal – TE-139, São Paulo, Brazil) for 19 h at 150 rpm and 30°C.

Cultivation

The cultures were carried out in 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 100 mL of medium supplemented with 4.0% (w/v) sugarcane molasses, 1.0 g/L (NH₄)₂SO₄, and 0.1% (v/v) of the salt stock solution. The flasks were inoculated with 10% (v/v) of the inoculum and incubated at 36°C and 200 rpm in a shaker (Tecnal – TE-139, São Paulo, Brazil) for 72 h to evaluate the kinetic parameters. For extraction assays, the cultivation time was 24 h.

Pre-treatment of cell-free broth

All samples subjected to extraction underwent acid precipitation to improve lipopeptide recovery from the fermentation broth. For this, the broth was centrifuged at 700 ×g for 15 minutes at 4°C. The pH of the supernatant was then adjusted to 2.0 by adding 2.0 M HCl. The solution was kept at 4°C for 12 hours. After this period, the precipitate formed was collected by centrifugation at 700 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C.17 The resulting precipitate was subsequently used in surfactin and iturin extraction assays.

Lipopeptide recovery assays

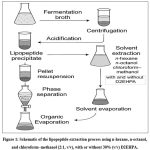

A 40 mL aliquot of broth was subjected to acid precipitation (see item 2.5). The resulting precipitate was resuspended in 10 mL of deionized water, and the pH of the solution was adjusted to 7.0 using 1 M NaOH. Then, 1 mL of organic solvent was gently layered over the solution. Extractions were carried out using the following organic solvents: n-hexane, n-octanol, and chloroform–methanol (2:1, v/v), with and without the addition of 30% (v/v) of the extractant di-(2-ethylhexyl) phosphoric acid (D2EHPA). The extraction was performed twice using the same amount of solvent. After extraction, the bioproduct was resuspended in an acetonitrile–methanol solution (1:1, v/v), and aliquots of the aqueous and organic phases were collected for biosurfactant concentration analysis (see item 2.7.3).17 Figure 1 shows a schematic representation of the lipopeptide recovery process employing the different solvent systems tested.

Extraction efficiency was calculated using the following Equation 1:

![]()

where Corg is the concentration of surfactin in the organic phase, and Cwi is the initial surfactin concentration in the aqueous phase.

|

Figure 1: Schematic of the lipopeptide extraction process using n-hexane, n-octanol, and chloroform–methanol (2:1, v/v), with or without 30% (v/v) D2EHPA. |

Analytical methods

Determination of substrate concentration

Substrate quantification was performed using the 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) method.18 Initially, 1.0 mL of the sample (cell-free fermentation broth), 0.5 mL of HCl, and 6.0 mL of water were heated in a water bath at 70°C for 10 minutes. The sample was then cooled, neutralized with 1.0 M NaOH, and diluted with distilled water. Aliquots of 0.5 mL of the hydrolyzed sample were transferred to test tubes containing 0.5 mL of DNS reagent and heated at 100°C for 5 minutes. Then, 4 mL of distilled water was added to the tubes, and absorbance was measured using a Ultraviolet (UV) spectrophotometer (Genesys 10, Thermo Scientific, USA) at 540 nm. Reducing sugar concentration was calculated based on a standard glucose calibration curve. All analyses were performed in triplicate.

Biomass concentration determination

Biomass concentration was determined by the dry weight method. Samples of 2.0 mL of fermentation broth were transferred to centrifuge tubes and spun at 15,000 × g for 15 minutes. The supernatant was removed, and the tubes containing the wet biomass were dried in a convection oven (TE-394/I, Tecnal, Brazil) at 70°C for 24 h.19 Biomass concentration (X) was estimated using Equation 2:

![]()

where m₁ is the mass of the centrifuge tube containing the cells and m₂ is the mass of the empty centrifuge tube.

Lipopeptide concentration determination

Lipopeptide concentration was determined by High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC; Accela-Thermo Scientific, USA) using a reversed-phase C18 column (Shim-pack CLC-ODS (M)TM, Shimadzu Co., Japan; 250 × 4.5 mm, 100 Å, 5 µm particle size). The mobile phase consisted of 20.0% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid (3.8 mM) and 80.0% (v/v) acetonitrile, with a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min at 30°C. Detection was performed at 205 nm using a UV detector. The injection volume was 20.0 µL, and the elution time was 30 minutes.20 Lipopeptide concentration was determined from a calibration curve using surfactin and iturin standards (95.0%, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA). All analyses were performed in triplicate.

Stability assays

For stability assays, 20 mL of cell-free broth were incubated at 20, 30, 40, 60, 80, and 100 °C for 30 minutes, then cooled to room temperature for surface tension measurements.21 To assess pH stability, samples were also subjected to a pH range from 3 to 10. All experiments were conducted in triplicate.

Critical micelle concentration (CMC)

CMC was estimated using the pendant drop technique with a Krüss DSA100 goniometer (Hamburg, Germany). Surface tension measurements were performed on cell-free broth samples. The CMC value was determined from the intersection point of the two linear segments on the plot of surface tension against surfactin concentration.

Fermentation parameter calculations

Lipopeptide productivity (surfactin and iturin) (PP, g/L·h) was calculated according to Equation 3:

where Pₜ and P₀ are the concentrations of product (surfactin or iturin, g/L) at a given time t and the start of cultivation, respectively; tf is the cultivation time (h).

The product yield relative to biomass (Yp/x, g product/g biomass) was calculated using Equation 4:

![]()

where P and X are the product and biomass concentrations at time t, respectively, and P0 and X0 are their respective initial concentrations.

Results

Production of surfactin and iturin by Bacillus subtilis UFPEDA 438

The lipopeptides surfactin and iturin were produced by submerged fermentation using sugarcane as a source of carbon and energy. Graph 1 shows the substrate consumption profile, cell concentration, and biosurfactant production by B. subtilis UFPEDA 438 after 72 hours of fermentation.

A lag phase was evident during the initial 4 hours of cultivation, with no significant increase in cell concentration. Maximum cell density (1.52 ± 0.01 g/L) was attained at 12 hours. The maximum biosurfactant concentrations were achieved after 24 hours of cultivation, corresponding to 187.01 ± 0.37 mg/L for surfactin and 10.80 ± 1.03 mg/L for iturin.

At 24 hours, product-to-biomass yield (Yₚ/ₓ) values were 0.03 g/g for surfactin and 0.02 g/g for iturin, with final productivities reaching 7.60 mg/L·h and 0.45 mg/L·h, respectively. By the end of fermentation, the residual substrate concentration was 70.44%.

|

Graph 1: Time-course profiles of substrate, biomass, and lipopeptide concentrations produced by B. subtilis UFPEDA 438 over time (36°C, 200 rpm agitation). (A) Surfactin concentration; (B) Iturin concentration. |

Lipopeptide recovery assays

Recovery assays were performed to evaluate the influence of solvent type and the presence of the complexing agent D2EHPA on the extraction of surfactin and iturin. The results showed statistically significant differences in both the concentration and recovery of surfactin (p < 0.05), as indicated by the distinct letters assigned to the treatments in Table 1. In contrast, for iturin, although numerical differences were observed among the treatments, Analysis of variance (ANOVA) did not indicate statistical significance (p = 0.476).

Table 1: Concentration (mg/L) and recovery (%) of surfactin and iturin obtained in extraction assays using B. subtilis UFPEDA 438.

| Solvent system | Surfactin | Iturin | ||

| Concentration (mg/L) | Recovery (%) | Concentration (mg/L) | Recovery (%) | |

| n-octanol | 200.08 ± 4.13ᵃ | 72.22a | 6.19 ± 5.75 | 51.57b |

| n-octanol + D2EHPA (30%) | 44.85 ± 0.33d | 18.36d | 9.52 ± 4.32 | 76.36a |

| n-hexane | 90.81 ± 4.09c | 35.01b | 3.15 ± 3.88 | 26.74c |

| n-hexane + D2EHPA (30%) | 79.12 ± 6.44c | 28.89c | 8.75 ± 5.96 | 72.96a |

| Chloroform–methanol (2:1, v/v) | 38.20 ± 1.29d | 14.87e | 9.75 ± 2.44 | 78.24a |

| Chloroform–methanol (2:1, v/v) + D2EHPA (30%) | 32.07 ± 0.58e | 12.55f | 8.18 ± 3.17 | 65.04a |

Note: Means followed by different letters in the same column differ significantly according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.05). No statistically significant difference was observed among treatments for iturin concentration (ANOVA, p = 0.476).

The highest surfactin concentration was obtained using n-octanol (200 ± 4.13 mg/L), with a recovery rate of 72.22%. The chloroform–methanol system (2:1, v/v) proved to be more effective for iturin recovery (78.24%), yielding a concentration of 9.75 ± 2.44 mg/L. However, this same solvent system exhibited significantly lower efficiency for surfactin recovery (14.87%).

Regarding extraction with n-hexane, this solvent demonstrated higher efficiency in recovering surfactin (35.01%) compared to iturin (26.74%). The addition of D2EHPA to n-hexane resulted in a surfactin recovery of 28.89%. Conversely, the addition of D2EHPA enhanced iturin recovery when combined with n-octanol (76.36%) and n-hexane (72.96%).

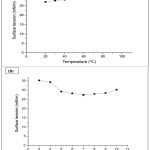

Stability study

To investigate the effect of temperature, the biosurfactants were exposed to a temperature range from 20 to 100°C (Graph 2a). The lipopeptides produced exhibited good thermal stability, with minimum and maximum surface tension values of 27.03 mN/m (at 20°C) and 29.85 mN/m (at 100°C), respectively.

To analyze the influence of pH, biosurfactant samples were exposed to a pH range from 3 to 10 (Graph 2b). The lipopeptides reached a minimum surface tension value of 27.38 mN/m at pH 7, exhibiting greater stability within the range of pH 6 to 9.

|

Graph 2: Effect of (A) temperature and (B) pH on surface tension (mN/m) of lipopeptides produced by B. subtilis UFPEDA 438. |

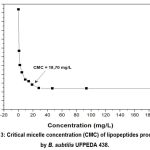

Critical micelle concentration (CMC)

The CMC of the biosurfactant was determined by measuring surface tension at various lipopeptide concentrations (mg/L). A surface tension versus concentration curve was constructed (Graph 3). Distilled water exhibited a surface tension of 72.00 ± 0.03 mN/m, which was reduced to as low as 27.02 ± 0.18 mN/m upon the addition of the biosurfactant. The lipopeptides produced by B. subtilis UFPEDA 438 reached a CMC of 18.70 mg/L, corresponding to a surface tension of 29.19 ± 0.07 mN/m.

|

Graph 3: Critical micelle concentration (CMC) of lipopeptides produced by B. subtilis UFPEDA 438. |

Discussion

Production of surfactin and iturin by Bacillus subtilis UFPEDA 438

The concentration of surfactin obtained in this study was similar to that reported in a previous study using the same microorganism, which reached 199 mg/L.17 Comparable results have been documented with a surfactin yield of 230 mg/L obtained using crude glycerol from the biodiesel industry as a substrate.22 However, these concentrations are lower than those reported in another study,23 which achieved 1.75 g/L using B. subtilis MTCC 2415 in a medium supplemented with salt and glucose.

The production of iturin has garnered increasing attention due to its promising industrial and agricultural applications. However, comprehensive studies on the biosynthesis of this antifungal lipopeptide remain scarce. The iturin concentration achieved here (10.80 mg/L) is lower than yields reported by other studies. For instance, high iturin concentrations (559 mg/L) were achieved by B. amyloliquefaciens BPD1 through supplementation with complex amino acids.24 Under optimized solid-state fermentation conditions, B. subtilis S3 produced 11.45 mg of iturin per gram of moist solid substrate.25 A subsequent study found a high iturin titer of 932 mg/L using B. subtilis RB14 after 120 hours of cultivation.26

The residual substrate concentration observed at the end of fermentation (70.44%) is comparable to results observed for B. subtilis LAMI005 cultivated in clarified cashew juice at varying substrate concentrations,27 with residual levels ranging from 61.4% to 69.8%.

Lipopeptide recovery assays

Surfactin and iturin are the two most prominent lipopeptide families, characterized by structurally similar frameworks and multiple homologues.28 Surfactin is composed of a cyclic heptapeptide linked to a β-hydroxy fatty acid, whereas in iturin, this moiety is replaced by a β-amino fatty acid. This fundamental structural difference can affect the molecule’s physicochemical properties, including the stability of the heptapeptide ring and its interaction with solvents29, which helps explain the divergent recovery behaviors observed.

The lack of statistical significance in iturin recovery across treatments (p = 0.476), despite numerical variations, suggests a more uniform behavior of this lipopeptide under the tested extraction conditions. This is possibly due to its lower sensitivity to solvent polarity and selectivity compared to surfactin.

The superior recovery of surfactin using pure n-octanol (72.22%) indicates a greater affinity of this lipopeptide for this solvent. In contrast, the chloroform–methanol system was highly effective for iturin but poor for surfactin. The low efficiency of n-hexane for surfactin recovery (35.01%) aligns with findings from a previous study using B. subtilis ATCC 21332, which also resulted in a low recovery yield (<21%).30 This outcome is likely due to the low polarity of n-hexane, which is not ideal for solubilizing the more polar regions of the surfactin molecule.

The addition of the liquid ion-exchange agent D2EHPA, previously effective for L-phenylalanine recovery,31 was tested for the first time for lipopeptide extraction. Although it did not improve surfactin recovery, the addition of D2EHPA proved highly beneficial for iturin recovery in specific systems, significantly enhancing the yield to 76.36% with n-octanol and 72.96% with n-hexane. This suggests a stronger and more selective interaction between D2EHPA and iturin molecules, likely through complex formation with the amino group in their β-amino fatty acid chains,32 thereby enabling more efficient extraction.

In conclusion, lipopeptide recovery using this method depends critically on the polarity of the biomolecule and the solvent selection. Due to its amphiphilic nature, surfactin exhibits variable interactions between its polar and nonpolar groups depending on the solvent used.33,34 This study demonstrates that both solvent polarity and the presence of the extractant D2EHPA significantly influence the recovery efficiency of surfactin and iturin, with iturin showing a particular affinity for systems containing the complexing agent.

Stability study

The thermal stability observed (a minimal change in surface tension from 27.03 to 29.85 mN/m over an 80°C range) is a key feature of biosurfactants. This property makes them suitable for applications in the pharmaceutical, food, and cosmetic industries, where sterilization is essential. Furthermore, they are promising candidates for enhanced oil recovery processes, which typically occur under high-temperature conditions.35

The finding that the lipopeptides exhibited greater stability within the pH range of 6 to 9, with optimal activity at pH 7, is consistent with previous reports, 21,35,36 which also observed enhanced stability under neutral to alkaline conditions. This behavior is attributed to increased micelle solubility and the prevention of secondary metabolite precipitation in alkaline environments.36 Similarly, the biosurfactant produced by B. subtilis BR-15 showed stability in the pH range of 7 to 9.37

The ability of biosurfactants to maintain stability across a broad range of temperatures and pH values has been supported by several studies.37,38,39 These properties broaden their potential applications in various industrial sectors.

Critical micelle concentration (CMC)

The reduction in surface tension is associated with the critical micelle concentration (CMC), which represents the minimum concentration required for micelle formation. The CMC value may vary depending on the size and shape of micelles, which are influenced by the types of groups present in the hydrophobic tail and the head groups of the monomers involved in micelle assembly.40

The lipopeptides produced in this study demonstrated a high surface-active performance, reducing the surface tension of water to 27.02 mN/m and achieving a low CMC of 18.70 mg/L. This represents a superior surface tension-reducing ability compared to lipopeptides synthesized by other strains. For instance, B. subtilis R1 grown in molasses-based medium showed a CMC of 39.5 ± 0.66 mg/L,41 and a CMC of 185 ± 10 mg/L was reported for lipopeptides produced by B. subtilis CN2.37 Even higher CMC values were recorded for B. subtilis ATCC 21332 (100 mg/L) and Bacillus sp. I-15 (200 mg/L).42

Lipopeptides are widely recognized for their efficiency and versatility, particularly due to their ability to reduce the surface tension of water to values below 30 mN/m.37 The result presented here is consistent with findings by Heryani and Putra,43 who achieved a surface tension reduction to 27.0 mN/m using a biosurfactant produced by Bacillus sp. A value of 26.52 mN/m was reached with B. atrophaeus 5-2a in another study.44 The high efficacy of a biosurfactant from B. subtilis BR-15 was also demonstrated, with surface tension lowered to 20.2 mN/m.3

In this context, given its low CMC and ability to significantly reduce surface tension, B. subtilis UFPEDA 438 emerges as a promising biosurfactant producer with potential applications in environmental remediation and enhanced oil recovery.

Conclusion

In summary, the biosurfactants produced by Bacillus subtilis UFPEDA 438 reached maximum production after 24 hours of cultivation, with surfactin and iturin concentrations of 187.01 ± 0.37 mg/L and 10.80 ± 1.03 mg/L, respectively. Stability tests confirmed that the lipopeptides were thermostable across a broad temperature range (20 to 100°C) and remained stable within a pH range from 6 to 9, making them suitable for applications under extreme conditions. In addition, a CMC value of 18.70 mg/L was recorded, indicating high surface activity.

Regarding lipopeptide recovery, the use of the complexing agent D2EHPA combined with the diluent solvents n-octanol and n-hexane enhanced the extraction efficiency of iturin, achieving recovery rates of 76.36% and 72.96%, respectively. However, this effect was not observed for surfactin, for which n-octanol alone yielded the highest recovery rate (72.22%). These findings highlight the need for further research to develop a recovery protocol that ensures efficient separation of lipopeptides, which may support future advances in this field.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank all individuals and institutions that contributed to this work, particularly the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN) for providing research facilities.

Funding Source

This study was supported by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), Brazil.

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

This statement does not apply to this article.

Ethics Statement

This research did not involve human participants, animal subjects, or any material that requires ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not involve human participants, and therefore, informed consent was not required.

Clinical Trial Registration

This research does not involve any clinical trials.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

Not Applicable

Authors contribution

Patrícia Maria Rocha: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing

Carlos Eduardo de Araújo Padilha: Methodology, Investigation, Extraction Process Input

Everaldo Silvino dos Santos: Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing, Guidance.

References

- De Almeida DG, Silva RC, Luna JM, et al. Biosurfactants: Promising molecules for petroleum biotechnology advances. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1718. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.01718

CrossRef - Hsu C-Y, Mahmoud ZH, Hussein UAR, Abduvalieva D, Alsultany FH, Kianfar E. Biosurfactants: Properties, applications and emerging trends. S Afr J Chem Eng. 2025;53:21–39. doi:10.1016/j.sajce.2025.04.002

CrossRef - Chen WC, Juang RS, Wei YH. Applications of a lipopeptide biosurfactant, surfactin, produced by microorganisms. Biochem Eng J. 2015;103:158–69. doi:10.1016/j.bej.2015.07.009

CrossRef - Ceresa C, Fracchia L, Sansotera AC, De Rienzo MAD, Banat IM. Harnessing the potential of biosurfactants for biomedical and pharmaceutical applications. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15(8):2156. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics15082156

CrossRef - Roy A, Khan MR, Mukherjee AK. Recent advances in the application of microbial biosurfactants in food industries: Opportunities and challenges. Food Control. 2024;163:110465. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2024.110465

CrossRef - Vigil TN, Felton SM, Fahy WE, et al. Biosurfactants as templates to inspire new environmental and health applications. Front Synth Biol. 2024;2:1303423. doi:10.3389/fsybi.2024.1303423

CrossRef - Dlamini B, Rangarajan V, Clarke KG. A simple thin layer chromatography based method for the quantitative analysis of biosurfactant surfactin vis-a-vis the presence of lipid and protein impurities in the processing liquid. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2020;25:101587. doi:10.1016/j.bcab.2020.101587

CrossRef - Wu G, Zhou J, Zheng J, et al. Construction of lipopeptide mono-producing Bacillus strains and comparison of their antimicrobial activity. Food Biosci. 2023;53:102813. doi:10.1016/j.fbio.2023.102813

CrossRef - Inès M, Dhouha G. Lipopeptide surfactants: Production, recovery and pore forming capacity. Peptides. 2015;71:100–12. doi:10.1016/j.peptides.2015.07.006

CrossRef - Gu Q, Yang Y, Yuan Q, et al. Bacillomycin D Produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens Is Involved in the Antagonistic Interaction with the Plant-Pathogenic Fungus Fusarium graminearum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2017;83(19):e01075-17. doi:10.1128/AEM.01075-17

CrossRef - Rasiya, Sebastian D. Iturin and surfactin from the endophyte Bacillus amyloliquefaciens strain RKEA3 exhibits antagonism against Staphylococcus aureus. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2021;36:102125. doi:10.1016/j.bcab.2021.102125

CrossRef - Meena KR, Kanwar SS. Lipopeptides as the antifungal and antibacterial agents: applications in food safety and therapeutics. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:473050. doi:10.1155/2015/473050

CrossRef - Zhen C, Ge XF, Lu YT, Liu WZ. Chemical structure, properties and potential applications of surfactin, as well as advanced strategies for improving its microbial production. AIMS Microbiol. 2023;9(2):195–217. doi:10.3934/microbiol.2023012

CrossRef - Kim SK, Shin KH. Marine Surfactants: Preparations and Applications. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2022. doi:10.1201/9781003307464

CrossRef - Rangarajan V, Clarke KG. Towards bacterial lipopeptide products for specific applications — a review of appropriate downstream processing schemes. Process Biochem. 2016;51(12):2176–85. doi:10.1016/j.procbio.2016.08.026

CrossRef - Biniarz P, Łukaszewicz M, Janek T. Screening concepts, characterization and structural analysis of microbial-derived bioactive lipopeptides: a review. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2017;37(3):393–410. doi:10.3109/07388551.2016.1163324

CrossRef - Rocha PM, Mendes ACS, Oliveira Júnior SD, et al. Kinetic study and characterization of surfactin production by Bacillus subtilis UFPEDA 438 using sugarcane molasses as carbon source. Prep Biochem Biotechnol. 2021;51(3):300–8. doi:10.1080/10826068.2020.1815055

CrossRef - Miller GL. Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal Chem. 1959;31(3):426–8. doi:10.1021/ac60147a030

CrossRef - Reis RS, Pacheco GJ, Pereira AG, Freire DMG. Biosurfactants: Production and Applications. In: Biodegradation – Life of Science. Rijeka, Croatia: InTech; 2013. doi:10.5772/56144

CrossRef - Wei YH, Chu IM. Enhancement of surfactin production in iron-enriched media by Bacillus subtilis ATCC 21332. Enzyme Microb Technol. 1998;22(8):724–8. doi:10.1016/s0141-0229(98)00016-7

CrossRef - Giri SS, Ryu EC, Sukumaran V, Park SC. Antioxidant, antibacterial, and anti-adhesive activities of biosurfactants isolated from Bacillus strains. Microb Pathog. 2019;132:66–72. doi:10.1016/j.micpath.2019.04.035

CrossRef - Faria AF, Teodoro-Martinez DS, Oliveira BGN, et al. Production and structural characterization of surfactin (C14/Leu7) produced by Bacillus subtilis isolate LSFM-05 grown on raw glycerol from the biodiesel industry. Process Biochem. 2011;46(10):1951–7. doi:10.1016/j.procbio.2011.07.001

CrossRef - Ganesan NG, Rangarajan V. A kinetics study on surfactin production from Bacillus subtilis MTCC 2415 for application in green cosmetics. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2021;33:102001. doi:10.1016/j.bcab.2021.102001

CrossRef - Wu JY, Liao JH, Shieh CJ, Hsieh FC, Liu YC. Kinetic analysis on precursors for iturin A production from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens BPD1. J Biosci Bioeng. 2018;126(5):630–5. doi:10.1016/j.jbiosc.2018.05.002

CrossRef - Shih IL, Kuo CY, Hsieh FC, Kao SS, Hsieh C. Use of surface response methodology to optimize culture conditions for iturin A production by Bacillus subtilis in solid-state fermentation. J Chin Inst Chem Eng. 2008;39(6):635–43. doi:10.1016/j.jcice.2008.05.005

CrossRef - Habe H, Taira T, Sato Y, Imura T, Ano T. Evaluation of yield and surface tension-lowering activity of iturin A produced by Bacillus subtilis RB14. J Oleo Sci. 2019;68(11):1157–62. doi:10.5650/jos.ess19182

CrossRef - Oliveira DWF, França IWL, Félix AKN, et al. Kinetic study of biosurfactant production by Bacillus subtilis LAMI005 grown in clarified cashew apple juice. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2013;101:34–43. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.06.011

CrossRef - Deng Q, Wang W, Sun L, et al. A sensitive method for simultaneous quantitative determination of surfactin and iturin by LC-MS/MS. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2017;409(1):179–91. doi:10.1007/s00216-016-9984-z

CrossRef - Hoefler BC, Gorzelnik KV, Yang JY, Hendricks N, Dorrestein PC, Straight PD. Enzymatic resistance to the lipopeptide surfactin as identified through imaging mass spectrometry of bacterial competition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(32):13082–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.1205586109

CrossRef - Chen HL, Juang RS. Recovery and separation of surfactin from pretreated fermentation broths by physical and chemical extraction. Biochem Eng J. 2008;38(1):39–46. doi:10.1016/j.bej.2007.06.003

CrossRef - Bi PY, Dong HR, Yu HB, Chang L. A new technique for separation and purification of l-phenylalanine from fermentation liquid: Flotation complexation extraction. Sep Purif Technol. 2008;63(2):487–91. doi:10.1016/j.seppur.2008.06.016

CrossRef - Chang Z, Zhou X, Bai H, Li D, Zhang L. Intensified reactive extraction of 4-hydroxypyridine with di(2-ethylhexyl) phosphoric acid in 1-octanol by using tributyl phosphate. Chin J Chem Eng. 2023;54:199–205. doi:10.1016/j.cjche.2022.03.021

CrossRef - Yang H, Li X, Li X, Yu H, Shen Z. Identification of lipopeptide isoforms by MALDI-TOF-MS/MS based on the simultaneous purification of iturin, fengycin, and surfactin by RP-HPLC. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2015;407(9):2529–42. doi:10.1007/s00216-015-8486-8

CrossRef - Otzen DE. Biosurfactants and surfactants interacting with membranes and proteins: Same but different? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2017;1859(4):639–49. doi:10.1016/j.bbamem.2016.09.024

CrossRef - Khopade A, Ren B, Liu XY, Mahadik K, Zhang L, Kokare C. Production and characterization of biosurfactant from marine Streptomyces species B3. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2012;367(1):311–8. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2011.11.009

CrossRef - Bezza FA, Chirwa EMN. Production and applications of lipopeptide biosurfactant for bioremediation and oil recovery by Bacillus subtilis CN2. Biochem Eng J. 2015;101:168–78. doi:10.1016/j.bej.2015.05.007

CrossRef - Sharma R, Singh J, Verma N. Production, characterization and environmental applications of biosurfactants from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens and Bacillus subtilis. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2018;16:132–9. doi:10.1016/j.bcab.2018.07.028

CrossRef - Varadavenkatesan T, Murty VR. Production of a lipopeptide biosurfactant by a novel Bacillus sp. and its applicability to enhanced oil recovery. ISRN Microbiol. 2013;2013:621519. doi:10.1155/2013/621519

CrossRef - Pathak KV, Keharia H. Application of extracellular lipopeptide biosurfactant produced by endophytic Bacillus subtilis K1 isolated from aerial roots of banyan (Ficus benghalensis) in microbially enhanced oil recovery (MEOR). 3 Biotech. 2014;4(1):41–8. doi:10.1007/s13205-013-0119-3

CrossRef - Cooper DG, Macdonald CR, Duff SJ, Kosaric N. Enhanced production of surfactin from Bacillus subtilis by continuous product removal and metal cation additions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1981;42(3):408–12. doi:10.1128/aem.42.3.408-412.1981

CrossRef - Joshi SJ, Desai AJ. Bench-scale production of biosurfactants and their potential in ex-situ MEOR application. Soil Sediment Contam. 2013;22(6):701–15. doi:10.1080/15320383.2013.756450

CrossRef - Fox SL, Bala GA. Production of surfactant from Bacillus subtilis ATCC 21332 using potato substrates. Bioresour Technol. 2000;75(3):235–40. doi:10.1016/s0960-8524(00)00059-6

CrossRef - Heryani H, Putra MD. Kinetic study and modeling of biosurfactant production using Bacillus sp. Electron J Biotechnol. 2017;27:49–54. doi:10.1016/j.ejbt.2017.03.005

CrossRef - Zhang J, Xue Q, Gao H, Lai H, Wang P. Production of lipopeptide biosurfactants by Bacillus atrophaeus 5-2a and their potential use in microbial enhanced oil recovery. Microb Cell Fact. 2016;15(1):168. doi:10.1186/s12934-016-0574-8

CrossRef

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.