Manuscript accepted on : 20-07-2025

Published online on: 23-09-2025

Plagiarism Check: Yes

Reviewed by: Dr. M M V Baig

Second Review by: Dr. Aisha Belal

Final Approval by: Dr. Wagih Ghannam

Joy Ogana1 , Victor Eshu Okpashi2*

, Victor Eshu Okpashi2* , Ogechukwu Frances Nworji1

, Ogechukwu Frances Nworji1 , Orji Ejike Celestine1

, Orji Ejike Celestine1 , Ezenwelu Chijioke Obinna1

, Ezenwelu Chijioke Obinna1 and Akpo David Mbu3

and Akpo David Mbu3

1Department of Applied Sciences, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awaka, Anambra State, Nigeria

2Department of Biochemistry, University of Cross River State, Nigeria.

3Department of Environmental Education, University of Calabar, Nigeria

Corresponding Author E-mail: vic2reshu@gmail.com

ABSTRACT: Earthworms play an important role in the soil ecosystem, it promotes soil structure and fertility. This study was designed to assess the toxic outcome of contaminated soil samples from an electrical transformer site and condensate dump site on the antioxidant enzymes of earthworms that are exposed to different dilutions of the polluted soil. The effects were assayed by measuring superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione reductases, glutathione peroxidase and metallothione activities, respectively. The result exposed a substantial rise in the activities of the enzymes assayed in a percentage dependent manner. It is concluded that the antioxidants are directly involved in the adaptive response of earthworm survival in a contaminated environment. The activities of glutathione reductase expressed as mean ± SD revealed a substantial rise in the contaminated soil samples compare to the control. Metallothione activities of earthworm exposed to different percentage soil dilutions rom condensate dumpsites, and electrical installation locations, revealed a reduction in metallothionine activities. Contaminants in the soil samples had a marked increase in catalase, SOD, and GR activities of earthworms after exposure. Therefore, one can infer that the contaminants in dumpsites and condensate may have severe effect on the health of the soil ecosystem and biodiversity.

KEYWORDS: Condensate; Electrical-Transformer; Forensic Science; Industrial-Biotechnology

| Copy the following to cite this article: Ogana J, Okpashi V. E, Nworji O. F, Celestine O. E, Obinna E. C, Mbu A. D. Effects of contaminated Soil from Electric Transformer and Condensate of Thermal Power Station on Antioxidants Enzyme and Metallothionein of exposed Earthworms. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(3). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Ogana J, Okpashi V. E, Nworji O. F, Celestine O. E, Obinna E. C, Mbu A. D. Effects of contaminated Soil from Electric Transformer and Condensate of Thermal Power Station on Antioxidants Enzyme and Metallothionein of exposed Earthworms. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(3). Available from: https://bit.ly/42Egeov |

Introduction

Anthropogenic endeavors, such as thermal power generation facilities, have persistently contributed to environmental degradation, thereby jeopardizing the safety of humans and other living organisms.1. Power-generating infrastructures are extensive undertakings that necessitate not only substantial financial investment but also a variety of natural resources, including fossil fuels and water, consequently exerting an immeasurable influence on the environment by imposing significant strain on the ecosystem Pokale.2 Thermal power plants represent a predominant source of electrical energy for any nation in the process of development. Approximately 60% of the electricity produced in Nigeria is supplied by thermal power facilities.3. In thermal power stations, electrical energy is derived from thermal energy. Given that heat is produced through the burning of fossil fuels, these facilities are also collectively designated as fossil-fueled power plants. Fossil fuels are primarily composed of a complex amalgamation of molecules referred to as hydrocarbons, which encompass straight-chain, branched, and cyclic hydrocarbons; polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons; and inorganic compounds Okpashi et al.4 At elevated concentrations, petroleum derivatives exhibit considerable toxicity to a multitude of organisms, including humans, terrestrial organisms, and aquatic life.5

Pollutants originating particularly from electrical transformers, degreasers, inhibitors used in cooling systems, detergents, lubricants, and wastewater produced in washrooms represent significant contributors to environmental contamination. In the context of a gas thermal plant, these pollutants, when introduced into the soil or aquatic systems, may become sequestered within aquatic strata or soil-dwelling organisms, notably earthworms, ultimately resulting in toxic concentrations. Such scenarios pose considerable risks to the health of these organisms due to prolonged exposure to elevated levels of these hazardous substances.6

Earthworms serve as an integral organism within terrestrial ecosystems, where they facilitate crucial chemical elemental transformations.7 Representing the predominant fraction of invertebrate biomass in numerous soil profiles, earthworms are both abundant and essential for various soil processes. The pivotal role of earthworms in the putrefaction of organic matter and the successive recycling of nutrients has brought in significant awareness, positioning them as valuable indicator for assessing the impact of soil pollutants.8 This interest has consequently spurred a substantial body of research dedicated to the field of environmental forensic and soil toxicology.9 They serve as optimal indicators of soil fertility enriched with organic compost. Furthermore, the manipulation of earthworms is relatively straightforward, facilitating the measurement of various life-cycle parameters, including growth indices, reproductive output, and the dynamics of pollutant accumulation and excretion,10 alongside biochemical responses involving antioxidant enzymes and metallothionein. Consequently, earthworms are regarded as appropriate organisms for conducting soil toxicity investigations.10 They utilize substantial quantities of organic soil for sustenance, generate significant quantities of biogenic compounds to influence the activities of microorganisms and by inhabiting their ecological niches.

Earthworms may encounter exposure through direct dermal contact with pollutants present in the soil solution or via the ingestion of pore water, contaminated food sources, and/or soil particulates. Given their interfaces with the soil milieu, they are profoundly obstructed by contaminants that penetrate the soil profile. Contamination arising from both organic and inorganic pollutants can significantly disrupt the functional integrity of soil ecosystems, either qualitatively or quantitatively, by interfering with the activities of soil fauna.11 This disruption may subsequently precipitate contamination within the terrestrial food web. The assimilation of contaminated earthworm tissue by predatory organisms can result in the bioaccumulation of toxic substances throughout the trophic hierarchy. The concentrations of pollutants in the soil can be determined through the assessment of the total soil contents are recognized as indicators of soil pollution.12

An exposure to organic or inorganic pollutants is well-documented as the bases for generating oxidative stress within cellular structures. A by-product of xenobiotic encompasses the generation of free radicals. Conversely, exposure to pollutants give way to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), including hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), superoxide (O₂⁻), and hydroxyl (OH) radicals Dazy et al.13 To mitigate the detrimental effects of reactive oxygen species (ROS), the cells must employ protective mechanisms involving enzymatic activities and low molecular weight antioxidants, such as glutathione and metallothioneins.14 Key antioxidants enzymes such as catalase, superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase, and glutathione reductase function in cellular response to oxidative stress.

Metallothioneins (MTs) are considered as low-molecular-weight, cysteine-rich, metal-binding proteins that participate in the maintenances of needed elements like copper (Cu) and zinc (Zn), while also facilitating the detoxification of nonessential metals such as silver (Ag), cadmium (Cd), and mercury (Hg).15,16 Beyond their role as chelators, MTs function as integral components of the antioxidant defense system, participating in the scavenging of free radicals and reactive oxygen species.17 These proteins consist of approximately 25%–30% cysteine, exhibiting a scarcity of aromatic or histidine residues. Metallothioneins from both vertebrates and invertebrates encompass two distinctive metal-thiolate clusters, which are dictated by the presence of metal-protein chelating Cys-X-Cys sequences, where X represents any amino acid, excluding cysteine.18

Despite the elucidation of amino acid sequences for over 50 invertebrate MT and MT-like proteins, the biochemical properties of earthworm metallothioneins remain largely unexplored. To date, five MT genes have been successfully cloned from species such as Lumbricus castaneus, Eisenia fetida, Lumbricus rubellus, and Lumbricus terrestris, with their expression exhibiting differential regulation as a reaction to various metals.19, 20 In addition to oxidative enzymes, the induction of metallothioneins serves as a prevalent biomarker within earthworm studies, utilized as an early indicator of exposure to metals toxicity in soil monitoring, thereby establishing the foundation for this investigation aimed at accurately determining the impact of thermal-condensate-contaminated soil on the biochemical indices of earthworms. This investigation covers a wide scope ranging from industrial biotechnology to environmental toxicology.

Materials and Methods

Acute toxicity tests with earthworms

Different percentages of contaminated soil were prepared by mixing 900g of contaminated soil and 100g of non-contaminated soil for 90 %, 800g and 200g for 80 %, 700 and 300 for 70 %, 600 and 400 for 60 %, 500 and 500 for 50 %, 400 and 600 for 40 %, 300 and 700 for 30 %, 200 and 800 for 20 %, 100 and 900 for 10 %, respectively. The different percentages of diluted soil were placed into small, perforated buckets. Thereafter, ten matured earthworms were placed in each bucket. To prevent the worms from escaping the containers were covered with mosquito net with tiny mesh. After 2 days of introduction, the surviving worms were counted. Three replicates were applied for this test.

Chronic toxicity test on the earthworm

70%, 50%, 30%, 10%, and 0% of the control (non-contaminated soil sample) were made in triplicate and put in a bucket for the chronic test. As in the acute test, ten earthworms were put in each bucket and covered with a mosquito net. Some were removed for biochemical testing after 14 days to test for the enzyme’s glutathione reductase, catalase, superoxide dismutase, and glutathione peroxidase, respectively. The biochemical tests (antioxidant enzyme analysis) were conducted after the remaining 28 days.

Sample preparation for earthworm

The earthworms’ guts were cleaned, frozen, and a 10% whole body homogenate was made in 50 mM phosphate buffer with a pH of 7.4 at the conclusion of the exposure period. To get the post-mitochondrial fraction (supernatant), the homogenate was subsequently ultra-centrifuged at 100,000 rpm for 60 minutes at 4 oC. Before being used, aliquots of the supernatant were kept at 80 OC. Based on the methodology outlined by Mirna and Branimir.21

Catalase activity Assay

Serum catalase activity was determined using the method outlined by Sinha’s22.

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity

To assess superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity, the serum was first diluted 20-fold. Then, 0.2 ml of this diluted serum was combined with 2.5 ml of a freshly prepared adrenaline solution. This mixture was quickly inverted in a cuvette to ensure thorough mixing. For comparison, a reference cuvette contained 2.5 ml of buffer, 0.3 ml of adrenaline, and 0.2 ml of the sample. The increase in absorbance was measured at 480 nm over a period of 150 seconds, with readings taken every 30 seconds.

The outcomes were determined using the equation provided below.

Where A0 = absorbance after 30 seconds

A3 =absorbance after 150 seconds

%inhibition = (increase in absorbance for substrate) x 100/ (increase in absorbance for blank)

Gpx-Reagent 2: (5mg); contains NADPH

GPx- Reagent3: (10ml); contains cumene Hydroperoxide. Sodium bicarbonate G

GPX- Reagent 4 🙁 1 m); contains KPO4 and GSSG-R

QC- Material: (0.5ml): contains human source material

Assay procedure

The prepared solution (25 ml of GPX-Assay + GPX-Reagent 1 + 20 µl GPX-Reagent 4) and the initial solution (2.14 ml GPX-Reagent 3 + 1 vial of GPX-Reagent 2) were transferred into the cuvette using a pipette. The reaction commenced with the addition of 30 µl of the sample or deionized water to the blank, followed by thorough mixing. The cuvette was sealed with paraffin, and the absorbance was measured at 340nm. The outcome was determined in this manner:

A =Asample Ablank

GPX activity = A/min x f; where f = factor

F = (TV/SV) X 103/ 6.22 where

TV = Total volume in ml

Sv = sample volume in ml

103 = coverts ml to l

6.22= Millimolar absorbance coefficient

Glutathione peroxidase (GPX) activity Assay

The glutathione peroxidase assay was performed using the techniques developed by Paglia and Valentine.23

Glutathione reductase (GR) activity

GR activity was assessed following the approach outlined by Mostafavi-Pour.24

Measuring Metallothioneins Levels

Metallothionein (MT) levels were determined using a method adapted from a previously established technique. First, tissue samples were prepared by adding three times their volume of a specific homogenization buffer (containing 0.5 M sucrose, 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer at pH 8.6, and 0.01% β-mercaptoethanol) to plastic tubes. These tissues were then blended to create a homogenate, which was divided into 3 mL aliquots. Next, the homogenates were centrifuged at 30,000 x g for 20 minutes to separate a supernatant rich in MT. To each 1 mL of this supernatant, 1.05 mL of cold absolute ethanol (at -20°C) and 80 µL of chloroform were added. The samples were then centrifuged again at a low temperature (0-4°C) at 6000 x g for 10 minutes.

The resulting supernatant was mixed with three volumes of cold ethanol and stored at -20°C for one hour to further purify the MT. For final purification and quantification, the supernatant was centrifuged once more at 6000 x g for 10 minutes. The solid pellets obtained were washed with a solution of ethanol, chloroform, and homogenization buffer (in an 87:1:12 ratio) and then centrifuged again under the same conditions. Finally, the purified pellets were dried using a nitrogen gas flow to remove any remaining solvent. These dried pellets were then re-suspended in 300 µL of a pH 7 solution containing 5 mM Tris-HCl and 1 mM EDTA. To this re-suspended MT fraction, 4.2 mL of 0.43 mM 5,5-dithiobis (nitrobenzoic acid) in a 0.2 M phosphate buffer (pH 8) was added. This mixture was allowed to sit for 30 minutes at room temperature. The concentration of reduced sulfhydryl groups, an indicator of MT levels, was then measured by spectrophotometry at 412 nm.

A standard curve using GSH (glutathione) was essential for accurate MT measurement. GSH was chosen as a benchmark because each of its molecules contains a single cysteine residue, making it suitable for quantifying cysteine levels, which are characteristic of MT.

Statistical Analysis

Investigations were carried out in triplicates and analyzed with Scientific Package for Science Student (SPSS) version 21. A one-way analysis of variance was used to compare the mean difference among samples. Significance was accepted at p < 0.05. Data are presented in mean ± standard deviation using descriptive statistics.

Results

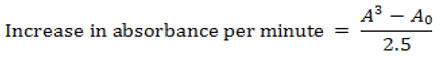

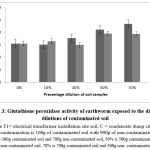

The catalase activity of earthworm exposed to different dilutions of contaminated soil

The catalase activity of earthworms subjected to various percentage dilutions of polluted soil samples is shown as mean ± SD in Figure 10. A notable rise (p < 0.05) in the catalase activities of all the contaminated soil samples was noted when compared to the control 0% (non-contaminated soil). In the soil of the condensate dump site, the activity of catalase depended on the percentage dilution, as increasing the contamination’s percentage dilution significantly raised catalase activities (p < 0.05). For the soil earthworm samples from the electrical transformer site, the enzyme activity notably (p < 0.05) rose at 10%; refer to Figure 1.

Superoxide dismutase activity of earthworm exposed to different dilutions of contaminated soil

The SOD expressed as mean ± SD across all the earthworms in the contaminated soil samples showed a significant increase (p < 0.05) compared to 0% (control). For the soil samples of earthworms from the electrical transformer site, the enzyme activity increased significantly at 10% contamination, but then markedly declined at 30% contamination and reached a stable level. This pattern was similarly noted with earthworms from the condensate dump site; a significant (p<0.05) rise of 10% was evident in Figure 2.

Glutathione peroxidase activity of earthworm exposed to the different dilutions of contaminated soil

The findings indicated a notable (p < 0.05) reduction in glutathione peroxidase activity expressed as mean ± SD of the control earthworm (0%), in contrast to the earthworm samples from contaminated soil. For soil earthworms at electrical transformer sites, the rise in enzyme activity was influenced by contamination; a higher percentage of contamination was linked to a rise in enzyme activity. In condensate soil, when the contamination percentage rises, the enzyme activity significantly increases (p < 0.05) up to a 30% contamination level, after which the activity decreases markedly (p < 0.05) but then rapidly rises again at 50% contamination (refer to Figure 3).

|

Figure 1: The catalase activity of earthworm exposed to different percentages dilution of contaminated soil sample. |

|

Figure 2: Superoxide dismutase activity of earthworm exposed to different dilutions of contaminated soil samples |

|

Figure 3: Glutathione peroxidase activity of earthworm exposed to the different dilutions of contaminated soil |

The Glutathione reductase activity of earthworms exposed to different dilutions of contaminated soil

The activity of glutathione reductase, expressed as mean ± SD, showed a significant increase (p < 0.05) in all contaminated soil earthworm samples when compared to the control. The activity of glutathione reductase in earthworms exposed to varying percentage dilutions of soil from electrical transformer installation sites was reliant on the level of contamination. For the earthworm samples from the condensate dump site, the rise in enzyme activity was also dependent on the percentage dilution of contamination, except for the 30% dilution, as shown in Figure 4.

Metallothionein activity of earthworm exposed to different dilution of contaminated soil

Figure 5 below shows the metallothionein activity in earthworms subjected to various percentage dilutions of soil from condensate dump sites and electrical transformer installation locations. The findings reveal a notable reduction (p < 0.05) in the metallothionein activity of earthworms subjected to 0% (control) in comparison to those exposed to various percentage dilutions of contaminated soil samples. For the soil earthworm at the electrical transformer site, the rise in metallothionein levels was contingent on the increase in percentage dilution of pollution. In the condensate soil samples, the rise in contamination percentage notably elevated (p < 0.05) the metallothionein levels up to 70% contamination, after which the value declined.

|

Figure 4: Glutathione reductase activity of earthworm exposed to different percentage dilution of contaminated soil samples. |

|

Figure 5: The metallothionein activity of earthworm exposed to different percentage dilution of contaminated soil samples. |

Discussion

Earthworms are the most crucial soil invertebrates in enhancing soil fertility. They decompose organic matter and release nutrients by enhancing aeration, drainage, and soil aggregation through their feeding and burrowing behaviors. Earthworms play a role in the diets of various higher animals and are used as bioindicators of soil health and moisture levels. The biochemical reactions of organisms to environmental stressors may serve as early indicators of pollution in the soil ecosystem. When earthworms are exposed to xenobiotics, their bodies can produce free radicals, such as reactive oxygen species (ROS). These include harmful molecules – hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), superoxide (O2−), and hydroxyl (OH) radicals.

Earthworm cells have a defense mechanism in place to shield them from the harm that these ROS can do to vital biological elements including proteins, DNA, and fats (lipids). Enzymes like glutathione reductase, catalase, superoxide dismutase, and glutathione peroxidase are part of this system. Additionally, they make use of smaller antioxidant molecules such as metallothionein and glutathione. By neutralizing free radicals, these defense mechanisms stop oxidative damage14

Our findings shows that the pollutants in the polluted soil samples caused a concentration-dependent increase in catalase, SOD, and GR activities in earthworms exposed to the soil from the electrical transformer site and the condensate disposal site. Similarly, a rise in metallothioneine and GPx was observed.

Under normal conditions, cells utilize their electron transport chains to convert oxygen into water and protect themselves from reactive oxygen species (ROS) damage using enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase26. SOD is a key component of an organism’s antioxidant defense, helping to prevent lipid peroxidation by neutralizing the initiators of this process and transforming superoxide radicals into hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) and oxygen (O₂)27.

In this study, earthworms exposed to contaminated soils from a condensate dump site and an electrical transformer site showed significantly increased SOD activity compared to those in uncontaminated control soil. This increase was dependent on the concentration of pollutants: SOD activity rose sharply at 10% contamination, dipped slightly at 30%, and then stabilized. These results suggest that the earthworms experienced oxidative stress due to exposure to the polluted soil environments.

Changes in superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity can serve as an indirect indicator of the toxic effects of pollutants on earthworms found in soils contaminated with condensate and transformer oil. These effects can lead to reduced earthworm diversity and a decline in soil fertility. Similar findings were reported by Adomako et al. 28, who observed that SOD activity increased during the early stages of phenanthrene exposure but decreased with prolonged exposure. Under normal physiological conditions, SOD maintains a balance that helps the organism manage reactive oxygen species. However, environmental stress can disrupt this balance, affecting the production and removal of oxygen radicals. Also, a low dose of atrazine stimulated SOD activity in earthworms, while higher concentrations suppressed it Leng.29

Catalase (CAT) is a key enzyme in the body’s natural detoxification process (Phase II), is essential for neutralizing harmful hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) by converting it into water. Our study found that exposing earthworms to soil contaminated with condensate and electric transformer waste led to an increase in catalase activity. Specifically, a 10% dilution of polluted soil resulted in a concentration-dependent rise in catalase, meaning higher contamination levels correlated with increased enzyme activity. This suggests the earthworms were actively working to combat the oxidative stress caused by the pollutants. However, the response of catalase isn’t always straightforward. Other studies have shown varied reactions including the Bell-shaped response which observed that exposing Eisenia fetida to chemicals like toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylene initially stimulated catalase activity but then inhibited it at higher pollutant concentrations, creating a “bell-shaped” curve Dada et al.30. This also, highlights that while low levels of pollution might trigger a protective response, excessive exposure can overwhelm the system, leading to enzyme dysfunction. Inhibition at high concentrations resulted in catalase reduction in L. rubellus after prolonged exposure to organophosphate insecticides Mirna and Branimir.21

Similarly, it has been found that olaquindox significantly decreased catalase activity in various parts of E. fetida Khaldoon et al.31. These findings suggest that high concentrations or prolonged exposure to certain pollutants can inhibit catalase activity, indicating severe toxicity and a compromised antioxidant defense system. This ultimately harms earthworm populations and reduces soil fertility. Interestingly, no significant change in catalase activity in E. fetida exposed to benzo(a)pyrene (B[a]P), a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) was found by Saint-Denis et al.32. This indicates that not all pollutants elicit the same catalase response, and some may not trigger an increase in CAT activity.

Another important enzyme, glutathione reductase (GR), is vital for cellular defense as it regenerates reduced glutathione (GSH), a powerful antioxidant, from its oxidized form. Our research showed elevated GR levels at 10% pollutant dilution, suggesting that the earthworms were indeed experiencing significant oxidative harm. However, at higher dilution concentrations, no further notable variation in GR content was observed. This could imply that beyond a certain point, the GR response plateaus or the enzyme system becomes overwhelmed.

Metallothioneins (MTs) are proteins crucial for mitigating environmental stress caused by various pollutants, especially metals. Their production is carefully regulated, and their increase in this study suggests the earthworms were not only managing vital metals like copper (Cu) and zinc (Zn) but also detoxifying non-essential toxic metals. This aligns with other research, including an observed significant rise in metallothionein levels in E. andrei exposed to minimal levels of essential metals (copper) and non-essential metals (Cadmium) Gaston et al.37 An increased metallothionein in Lumbricus mauritii exposed to lead (Pb) and zinc (Zn) contaminated soil was observed by Maity et al.38 Studies involving Lumbricus terrestris exposed to Cadmium, copper, and mercury also support the notable induction of metallothioneins.39

These consistent findings across different studies underscore the importance of metallothioneins in earthworm metal detoxification. The combined findings indicate that earthworms possess a remarkable capacity to tolerate moderate levels of pollutants and effectively manage oxidative stress. Their ability to adjust internal biochemical reactions, such as increasing catalase and glutathione reductase activity or inducing metallothionein production, helps mitigate the harmful impacts of chemicals. This highlights the crucial role of initial biochemical responses in assessing the potential negative effects of chemicals on the environment. This research supports the idea that antioxidant enzymes and antioxidant concentrations can fluctuate based on pollutant stress levels, making them valuable general biomarkers for early and low-concentration detection of pollution impacts in terrestrial ecosystems Wang et al.35

More so, while this study highlights the potential of these biomarkers, it also points out the inconsistent and unreliable dose-response correlations. This is a critical challenge in using these markers for precise environmental monitoring. Future research should focus on understanding the factors that contribute to this variability, such as the specific type of pollutant, duration of exposure, environmental conditions, and the earthworm species. Also, considering specificity against general biomarkers: Catalase and glutathione reductase are general indicators of oxidative stress. While it will be useful for initial screening, they don’t pinpoint the specific pollutant causing the stress. Metallothioneins, being more directly involved in metal binding, offer slightly more specificity for metal contamination. Developing a panel of biomarkers that provides both general stress indicators and more specific pollutant-related responses would be highly beneficial. Going beyond enzyme activity, although enzyme activity is important, examining other aspects of earthworm health, such as growth, reproduction, DNA damage, and histological changes, can provide a more comprehensive picture of pollutant impact. Integrating these different levels of biological response can strengthen the validity of earthworms as bioindicators.

Conclusion

The research found that exposure to polluted soil samples increased the activity of key enzymes like catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and glutathione reductase (GR) in earthworms. These enzymes are crucial for combating reactive oxygen species (ROS), which cause cellular damage. Specifically, SOD activity peaked at a 10% contaminant concentration before leveling off, indicating stress. Similarly, catalase activity showed a concentration-dependent increase with higher pollution levels. While these responses suggest earthworms can adapt to a certain degree of contamination, prolonged or severe exposure can negatively impact earthworm populations and soil fertility.

Metallothioneins (MTs), proteins involved in countering environmental stress from pollutants, particularly metals, were also elevated in the study. This indicates the earthworms were actively regulating essential metals like copper and zinc while detoxifying non-essential toxic metals. Overall, the findings suggest that the responses of antioxidant enzymes and metallothioneins in earthworms could serve as valuable biomarkers for assessing environmental pollution. However, the study also noted inconsistencies in these biomarker responses, highlighting a lack of reliable dose-response correlations.

Moving forward, leveraging earthworms as reliable bioindicators for soil health requires addressing the current limitations in biomarker consistency. Future research should focus on standardizing monitoring protocols. By developing standardized methods for earthworm exposure studies, including consistent contaminant concentrations, exposure durations, and environmental conditions, will be crucial. This will help reduce variability and improve the reliability of biomarker responses. Instead of relying on single enzymes, a more comprehensive approach would involve using a panel of diverse biomarkers. This panel could include not only enzymatic activities and protein levels but also genetic markers (e.g., gene expression of stress-related proteins), cellular damage indicators (e.g., DNA damage), and even behavioral changes. A multi-faceted approach could provide a more robust and nuanced understanding of pollutant effects. Real-world contamination often involves complex mixtures of pollutants. Future studies should investigate the cumulative and synergistic effects of multiple contaminants on earthworm biomarkers, rather than focusing on single substances. This will better reflect environmental realities. Although, controlled laboratory studies provide valuable mechanistic insights, validating these biomarkers in diverse field settings is paramount. Long-term field studies in contaminated areas can help confirm the ecological relevance and predictive power of these indicators under real-world conditions. The ultimate goal is to link biomarker responses to actual ecological impacts, such as changes in earthworm diversity, population dynamics, and the overall health and fertility of the soil. This integration will demonstrate the practical utility of earthworm biomarkers in environmental risk assessment and management. By pursuing these avenues, we can refine the use of earthworms as sensitive and effective sentinels of soil pollution, providing early warnings and guiding more sustainable environmental practices.

Acknowledgment

We hereby thank Mr. Paul Odey and Lady Esther for their supports and guide during our investigation.

Funding Sources

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

This statement does not apply to this article.

Ethics Statement

This research did not involve human participants, animal subjects, or any material that requires ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not involve human participants, and therefore, informed consent was not required.

Clinical Trial Registration

This research does not involve any clinical trials.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources –

Not Applicable

Author Contributions

Joy Ogana and Victor Eshu Okpashi: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Original Draft.

Ogechukwu Frances Nworji: Data Collection, Analysis, Writing – Review & Editing.

Orji Ejike Celestine, and Ezenwelu Chijioke Obinna: Visualization, Supervision ,Project Administration.

Akpo David Mbu: Resources and Supervision.

Reference

- Akhtar N, Syakir Ishak MI, Bhawani SA, Umar K. Various Natural and Anthropogenic Factors Responsible for Water Quality Degradation: A Review. Water. 2021;13(19):2660. doi:10.3390/w13192660.

CrossRef - Pokale WK. Effects of thermal power plants on environment. Scientific Reviews and Chemical Communication. 2012;2(2):212-215.

- Adeoye OS, Bamisaye AJ. Performamance evaluation and analysis of Omotoso power plant in Nigeria. Innovative Energy and Research. 2016; 5:134.

- Okpashi VE, Ogugua VN, Onwurah INE, Ubani CS, Ezike TC. Comparative assessment of TPHs and bioaccumulation in some fresh fish species in the Qua Ibeo River of Eket of Akwa Ibom State in Nigeria. Bangladesh J Sci Ind Res. 2016;51(2):147-154.

CrossRef - Shamiyan R, Khan JI, Nirmal K, Rita NK, Jignasha GP. Physicochemical properties, heavy metal content and fungal characterization of an old gasoline-contaminated soil site in Anand, Gujarat, India. Environmental and Experimental Biology. 2013; 11:137-143.

- Okpashi VE. Estimation Of Redox-Sensitive Metals in Lafarge Cement Company’s Area in Akamkpa Nigeria: Assessment of Ecological Health Risk. Science World Journal. 2024;19(1). doi:10.4314/swj. v19i1.27.

CrossRef - Ogana J, Okpashi VE, Nworji OF, Oriji EC, Eze SO, Onwurah INE. Assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, polychlorinated biphenyl, in used electrical transformer oil, condensate, thermal power effluent soil and dump sites. Science World Journal. 2024;19(3). doi:10.4314/swj. v19i3.1.

CrossRef - Gudeta K, Kumar V, Bhagat A, et al. Ecological adaptation of earthworms for coping with plant polyphenols, heavy metals, and microplastics in the soil: A review. Heliyon. 2023;9(3): e14572. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon. 2023.e14572.

CrossRef - Spurgeon DJ, Weeks JM, Van Gestel CA. A summary of eleven years’ progress in earthworm ecotoxicology. Pedobiologia. 2003;47(5-6):588-606.

CrossRef - Okpashi VE, Igori W, Akpo DM. Crude oil pollution and bioremediation using brewery mash and earthworm (Nsukkadrilus mbae) a consortium to cleaning-up and restoring the soil fertility potential. J Petroleum Environ Biotechnol. 2015; 6:223. doi:10.4172/2157-7463.1000223.

CrossRef - Jun D, Thierry B, James HR, et al. Heavy metal accumulation by two earthworm species and its relationship to total and DTPA-extractable metals in soils. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2004;36(1):91-98. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2003.09.001.

CrossRef - Sheppard SC. Summary of phytotoxic levels of soil arsenic. Water Air Soil Pollution. 1992; 64:539-550.

CrossRef - Dazy M, Masfaraud JF, Férard JF. Induction of Oxidative Biomarkers Associated with Heavy Metal Stress in Fontinalis antipyretica Chemosphere. 2009; 75:297-302.

CrossRef - Valavanidis A, Vlahogianni T, Dassenakis M, Scoullos M. Molecular Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress in Aquatic Organisms in Relation to Toxic Environmental Pollutants. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 2006; 64:178-189.

CrossRef - Costello LC, Guan Z, Franklin RB, Feng P. Metallothionein can function as a chaperone for zinc uptake transport into prostate and liver mitochondria. Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry. 2004;98(4):664-666.

CrossRef - Amiard JC, Amiard-Triquet C, Barka S, Pellerin J, Rainbow PS. Metallothioneins in aquatic invertebrates: their role in metal detoxification and their use as biomarkers. Aquatic Toxicology. 2006;76(2):160-202.

CrossRef - Min KS. The Physiological Significance of metallothionein in oxidative stress. Journal of Pharmaceutical Society Japan. 2007;127(4):695-702.

CrossRef - Stürzenbaum SR, Winters C, Galay M, Morgan AJ, Kille P. Metal ion trafficking in earthworms—Identification of a cadmium-specific metallothionein. J Biol Chem. 2001; 276:34013-34018.

CrossRef - Gruber C, Stürzenbaum S, Gehrig P, et al. Isolation and characterization of a self-sufficient one-domain protein—(Cd)-metallothionein from Eisenia foetida. Eur J Biochem. 2000; 267:573-582.

CrossRef - Gudeta K, Kumar V, Bhagat A, et al. Ecological adaptation of earthworms for coping with plant polyphenols, heavy metals, and microplastics in the soil: A review. Heliyon. 2023;9(3): e14572. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon. 2023.e14572.

CrossRef - Mirna V, Branimir KH. Different Sensitivities of Biomarker Responses in Two Epigeic earthworm species after exposure to pyrethroid and Organophosphate Insecticides. Archive in Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 2012; 6:22-31.

- Sinha AK. Colorimetric assay of catalase. Analytical Biochemistry. 1972; 47:389-394.

CrossRef - Paglia DE, Valentine WN. Studies on the quantitative and qualitative characterization of erythrocyte glutathione peroxidase. J Lab Clin Med. 1967;70(1):158-169.

- Mostafavi-Pour Z, Khademi F, Zal F, Sardarian AR, Amini F. In Vitro Analysis of CsA-Induced Hepatotoxicity in HepG2 Cell Line: Oxidative Stress and α2 and β1 Integrin Subunits Expression. Hepat Mon. 2013;13(8):e11447. doi:10.5812/hepatmon.11447.

CrossRef - Dabrio M, Rodríguez AR, Bordin G, et al. Recent developments in quantification methods for metallothionein. J Inorg Biochem. 2002;88(2):123-134. doi:10.1016/s0162-0134(01)00374-9.

CrossRef - Bhattacharyya A, Chattopadhyay R, Mitra S, Crowe SE. Oxidative stress: an essential factor in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal mucosal diseases. Physiol Rev. 2014;94(2):329-354. doi:10.1152/physrev.00040.2012.

CrossRef - Zheng M, Liu Y, Zhang G, et al. The Applications and Mechanisms of Superoxide Dismutase in Medicine, Food, and Cosmetics. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023;12(9):1675. doi:10.3390/antiox12091675.

CrossRef - Adomako MO, Xue W, Roiloa S, et al. Earthworms Modulate Impacts of Soil Heterogeneity on Plant Growth at Different Spatial Scales. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2021; 12:735495. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.735495.

CrossRef - Leng C. (2007). Effects of Low-Level Atrazine Exposure on the Activities of Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) in Carassius auratus. Journal of Agro-Environment Science.

- Dada E.O, Akinola M.O, Owa S.O, Dedeke G.A, Aladesida A.A, Owagboriaye F.O, et al, Efficacy of Vermiremediation to Remove Contaminants from Soil. J Health Pollut. 2021, 11(29):210302. doi: 10.5696/2156-9614-11.29.210302.

CrossRef - Khaldoon S, Lalung J, Maheer U, Kamaruddin M.A, Yhaya M.F, Alsolami E.S, et al., A Review on the Role of Earthworms in Plastics Degradation: Issues and Challenges. Polymers (Basel). 2022 14(21):4770. doi: 10.3390/polym14214770.

CrossRef - Saint-Denis M, Narbonne J.F, Arnaud C, Thybaud E, Ribera D. Bio- Chemical Responses of the Earthworm Eisenia fetida andrei Exposed to Contaminated Artificial Soil: Effects of Benzo(a)pyrene. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 1999, 31: 1837-1846.

CrossRef - Ran X, Amjad A, Yaqiong, X., Hamada, A., Ronghua, L., Yanbing, L., Nanthi, B., Sabry, M., Shaheen, J. R., & Zengqiang, Z (2022). Earthworms as candidates for remediation of potentially toxic elements contaminated soil and mitigating the environmental and human health risks: A review, Environment International, Volume 158, doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2021.106924

CrossRef - Zeb A, Li S, Wu J, Lian J, Liu W, Sun Y. Insights into the mechanisms underlying the remediation potential of earthworms in contaminated soil: A critical review of research progress and prospects. Sci Total Environ. 2020; 740:140145. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140145.

CrossRef - Wang Y, Wang ZJ, Huang JC, Chachar A, Zhou C, He S. Bioremediation of selenium-contaminated soil using earthworm Eisenia fetida: effects of gut bacteria in feces on the soil microbiome. Chemosphere. 2022; 300:134544. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.134544.

CrossRef - Mosleh Y, Paris-Palacios S, Ahmed M, Mahmoud F, Osman F, Biagianti-Risbourg S. Effect of chitosan on oxidative stress and metahothionein in aquatic worm Tubifex tubifix (oligochaeta, Tubificidac). Chemosphere. 2006; 67:167-175.

CrossRef - Gaston KJ, Davies RG, Orme CDL, et al. Sptial turnover in the global avifauna. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 2007;274(1618):1567-1574.

CrossRef - Maity, S.Bhattacharya, S. and Chaudhury, S. (2009). Metallothionein response in earthworms Lampito mauritii (Kinberg) exposed to fly ash. Chemosphere,77: 319–324.

CrossRef - Calisi, A., Lionetto, M.G. & Schettino, T. (2009). Pollutant-induced alterations of granulocyte morphology in the earthworm Eisenia foetida. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 72(5):1369-1377.

CrossRef

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.