Manuscript accepted on : 09-09-2025

Published online on: 18-09-2025

Plagiarism Check: Yes

Reviewed by: Dr. Vivek Anand

Second Review by: Dr. Aisha Belal

Final Approval by: Dr. Wagih Ghannam

Nano-Based Antibiofilm Strategy Against Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Anju Sivasankaran* and Sarada Jonnalagadda

and Sarada Jonnalagadda

Department of Microbiology, Bhavan’s Vivekananda College of Science, Humanities and Commerce, Sainikpuri, India.

Corresponding Author E-mail:anjunair227 @gmail.com

ABSTRACT: The biofilm formation in P. aeruginosa is controlled by a network of signalling systems well-known as quorum sensing. This QS system is known to control the virulence factors like production of siderophores, rhamnolipids, exopolysaccharide matrix and motility. Pseudomonas infections have been proven to be resistant to most of the conventional antibiotics and their susceptibility is achieved only at their high concentrations. Since the development of biofilm in P. aeruginosa is a consequence of multiple pressures that has triggered resistance to antibiotics, targeting biofilm needs to be based on mode of action that can weaken more than one of its features. Biogenic Silver Nanoparticles (BSNPs) have been proved to have the highest antimicrobial property and highest level of biocompatibility when compared to other metal nanoparticles. In the present study Biogenic Nano Formulation (BgNF) was developed as an antibiofilm agent which showed 96% of biofilm inhibition and 89.93% of biofilm dispersal. BgNF could inhibit exopolysaccharide matrix, and rhamnolipids production by 100%. Siderophores reduction was noted to be 95% for PVD while 92% was observed for PCH. Swarming motility also was found to be inhibited by 69%. Absence of QS signals was also identified by UPLC-MS analysis.

KEYWORDS: Biofilm; Biogenic Nanoformulation; Biogenic Silver nanoparticles; Chromobacterium violaceum4212; Pseudomonas aeruginosa YU-V10

| Copy the following to cite this article: Sivasankaran A, Jonnalagadda S. Nano-Based Antibiofilm Strategy Against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(3). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Sivasankaran A, Jonnalagadda S. Nano-Based Antibiofilm Strategy Against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(3). Available from: https://bit.ly/4gwB1Ab |

Introduction

Formation of biofilm is one of the important traits among infectious pathogens which promotes multi drug resistance. Resistance to drugs is accelerated in biofilm lifestyle due to evolution in mechanisms of drug inactivation, reduced penetrability and existence of cells that have low metabolic rate. Therefore, there is a constant demand for development of antibiofilm agents since the conventional antibiotics fail to show a prolonged and sustainable effect. Typical structural organization of biofilm microcolonies enclosing the bacterial cells, is known to protect them from instantaneous exposure to drugs as they are encapsulated by extracellular polymeric matrix. Bacterial cells in the biofilm undergo drastic transformation at genetic level, which enhance the virulence factor expressions.1 The bacterial cells within a biofilm community have diversified metabolic activity and heightened quorum sensing features that build a regulation to promote survival under stress conditions. Most of the actively motile, metabolizing cells are found to flourish on the surface layers while the innermost layers are populated by dormant inactive cells. Consequently, antibiotics are effective only on the bacteria at peripheral layers of the micro colonies that are actively proliferating. Whereas the core of biofilm is predominated by dormant cells which remain unaffected to treatment and thus, may elevate the conditions to chronic infection after the antibiotic therapy is withdrawn.2

As an opportunistic pathogen, Pseudomonas aeruginosa is known to develop into profound biofilm. The adaptability of this ubiquitous organism to diverse environments and its ability to develop resistance to many classes of antimicrobial agents brings in a major threat to human health. Infections caused by this organism have become a matter of concern due to its ability to cause chronic infections that are mostly resistant to several antibiotics and host immune responses.3

Owing to the lack of effective treatment against the thriving biofilm-based infections in Pseudomonas sps, there exists a constant quest for development of potent antibiofilm agents that have the ability to penetrate into the biofilm matrix and prevent induction drug resistance. At present most of the therapies against biofilm have been carried out with a combinatorial approach. Antibiotics found to be resistant initially upon combination with QQ agents or nanoparticles had become potentially effective. Among the different metal nanoparticles, silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) were reported to have greater antimicrobial potential due to their broad spectrum of action at cellular level.4

Over the years, development of antibiofilm agents against various pathogens have been reported but a definitive respite has not been achieved with reference to recalcitrant infections. Even though the majority of clinical pathogens are reported to form biofilm, studies on P. aeruginosa are found to have outstanding relevance in biofilm research due to their structural and regulatory complexity hence chosen as a model organism to assess the efficacy of antibiofilm agents.5 Green synthesized silver nanoparticles are cost effective, nontoxic and high output forms of therapeutic agents. In a biologically mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticle, phytochemicals and microbial enzymes that have reducing antioxidant properties attribute to the reduction of metal ions into metal nanoparticles there by making them more compatible. Secondary metabolites of plants like phenolic compounds, glycosides, flavonoids, steroids and other bio active constituents are responsible for the biological compatibility factor for green synthesized silver nanoparticles. This property enhances the attachment of silver nanoparticles to the cell wall of bacteria and easy penetration through the cellular membrane. The disorganization of the cell membrane results in leakage of the cellular contents. Apart from that, biogenic silver nanoparticles have easy penetration abilities through the exopolysaccharide (EPS) matrix when compared to conventional antibiotics This results in exposure of the biofilm cell to high concentration of nanoparticles causing immediate cell death.

In the earlier study, determination of quorum quenching activity of extracts as well as that of biogenic silver nanoparticles (BSNPs) synthesized from medicinal aqueous extracts of Garcinia cambogia, Terminalia chebula, Trachyspermum ammi, Zingiber officinale and Agaricus bisporous was established using Chromobacterium violaceum4212. The results indicating the potential QQ activity has been communicated to peer reviewed journal that is yet to be published. After establishing the QQ potential and anti-virulent properties of BSNPs against C. violaceum 4212 strain, Pseudomonas aeruginosa YU-V10, a clinically established urinary catheter pathogen having multi drug resistance was selected as a test organism to develop the antibiofilm formulation using the BSNPs.

Further studies on a clinical pathogen, owing to the medical scenario where biofilm resistant strains being a menace in devices such as catheters, was carried out against a clinical isolate YU-V10 purchased from MCC, Pune. The study intended to develop a nano formulation against P. aeruginosa YU-V10 biofilm, that can have a broad range of mode of action, greater penetrability into the matrix and overcome challenges of drug resistance. Since biofilm are primarily regulated by the quorum sensing (QS) mechanism, inhibition of this would be a promising approach to target biofilm. Pseudomonas aeruginosa YU-V10 (MCC 3457), urinary catheter isolate has been selected to evaluate the efficacy of BSNPs. The strain with accession number MCC 3457 has been purchased from NCCS, Pune. This is a multi-drug-resistant clinical isolate with a strong biofilm forming ability and diverse virulent factors.6

This multi drug resistant strain was chosen in present study because of its ability to form biofilm, produce multiple virulence factors like rhamnolipids, pyoverdine, pyochelin and swarming motility.

Materials and Methods

Biofilm dynamics of Pseudomonas aeruginosa YU-V10

This study was carried out to identify the ideal media and incubation period for maximum biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa YU-V10. The actively growing P. aeruginosa culture at 0.5 OD600 corresponding to 1x 108 CFU/ml, was inoculated into the sterile Nutrient Broth and Luria Broth and was evaluated for biofilm development at 24 hrs. interval for five days. The biofilm quantification was performed by method O’Toole G et al., 2000 as described above. The experiment was set up in triplicates and the OD values at 630 nm were determined to figure out the incubation period with respect to the media for maximum biofilm formation.

Determination of MBEC of BSNPs against P. aeruginosa YU-V10

Overnight grown P. aeruginosa YU-V10 culture was diluted in sterile nutrient broth to obtain cell density equivalent to 0.5 McFarland corresponding to 1x 108 CFU/ml. The concentrations range for BSNPs tested were from 2µg/ml, 4µg/ml, 6µg/ml ,8µg/ml, 10µg/ml and 12µg/ml. To 50 µl of nutrient broth, aliquots of BSNPs with the above-mentioned concentrations were added making it to 100 µl volume, this was followed by addition of 10µl of Pseudomonas culture to all wells in the microtiter plate. After incubation for 24 hrs., resazurin indicator was added to determine the viability of the cells which was indicated by color change from blue to pink and thereby MIC was determined. The MIC concentrations and the next higher concentrations containing test solutions were plated on the solid media plates to detect the bacteriostatic as well as bactericidal concentrations based on the presence and absence of bacterial colonies. (Loo YY et al., 2018). The MIC values were also referred to as Minimum Biofilm Eradication Concentration (MBEC).7

Extraction of Exopolysaccharide (EPS)

P. aeruginosa culture treated with and without BgNF was centrifuged at 3000g for 20 min at room temperature to harvest cell pellet. Later these cells were resuspended in 1.5ml of 30% (w/v) NaOH and boiled for 15min in water bath and the suspension was centrifuged at 15000 g to obtain the supernatant. To precipitate EPS from the supernatants drops of 60% cold ethanol were added.8

Quantification of Exopolysaccharide

After extraction, precipitated EPS was resuspended in the sterile water and mixed with 7ml of 77% (v/v) H2SO4. The mixture was cooled in an ice bath for 10min. To this solution, 1ml of 1% (w/v) cold Tryptophan was added and boiled 20mins for complete hydrolysis. Acid hydrolysis of EPS produced a furan which condenses with tryptophan to form a colored product which was measured after cooling at OD500. Calibration curves or standard graph of dextran was constructed to estimate the EPS.

Extraction and Estimation of Rhamnolipids

For extraction, 5ml of overnight grown P. aeruginosa culture was centrifuged at 3200g, for 5 min at 240 C. Cell free supernatants were collected and acidified with 1N HCl to pH 2.0. Then 4ml of supernatant was mixed with 4ml of ethyl acetate and vigorously vortexed at 600 rpm for 20 sec. Upper Rhamnolipid containing ethyl acetate phase was transferred into a separate tube. This step of rhamnolipid extraction with ethyl acetate was repeated 3 times. Ethyl acetate extracts were dried in the evaporator for further analysis.

1 ml of chloroform (lower) phase was transferred in a clear microcentrifuge tube. It was mixed with 500µl of HCl 0.2 N. The mixture was centrifuged at a speed of 100 x g for 1min and the solution was left at room temperature for 10min to optimize methylene blue extraction in HCl. Later 200µl of upper acidic phase complexed methylene blue was transferred in 96-well microplate and the absorbance was measured at 638nm against HCl 0.2 N blank. The estimation of Rhamnolipid was done against the standard curve plotted.9

Detection of Pyoverdine (PVD)

For detection of pyoverdine, 100µl of Pseudomonas culture was mixed with 1ml of Pyridine Acetic acid buffer (50mM, pH 5.0). The mixture was taken in a quartz cuvette and absorbance was recorded at 360 nm and 380 nm against a blank of Pyridine Acetic acid Buffer. The maximum absorbance at wavelength 360 nm and 380 nm indicates presence of pyoverdine. (Hoegy F et al., 2014) The absorbance values were recorded in triplicates and concentrations were determined using Molar Extinction Coefficient (Ɛ). The formula: Concentration (C) = A/ Lx Ɛ, where C- concentration; A- Absorbance, L- Path Length. The Ɛ value for PVD is 16,500 M-1 Cm-1 .10

Extraction of Pyochelin (PCH)

Extraction of Pyochelin was carried out by adding solid citric acid to 100ml of Pseudomonas culture supernatant to obtain a pH 3.0. Twice acidified supernatant was extracted with 50ml of CH2Cl2 in a separating funnel. Organic phase was collected and dried over Magnesium Sulfate.

Detection of Pyochelin (PCH)

Extracted PCH was dissolved in methanol – water solution. Absorbance was measured at 313 nm against a blank of methanol- water. The absorbance values were recorded in triplicates and concentrations were determined using Molar Extinction Coefficient (Ɛ). The formula: Concentration (C) = A/ Lx Ɛ, where C- concentration; A- Absorbance, L- Path Length. The Ɛ value for PCH is 4,900 M-1 Cm-1.

Results

Study of biofilm dynamics of Pseudomonas aeruginosa YU-V10 (MCC 3457)

Experiments were performed in two medias i.e., Nutrient Broth and Luria Broth. Biofilm formation has been quantified by crystal violet staining method (O’Toole GA, Kolter R) in microtiter plates. Pseudomonas aeruginosa YU-V10 (MCC 3457) has shown an increase in the biofilm development for 4 days after which no noteworthy increase in the absorbance. The trend line showed a significant enhancement in the biofilm constituents up to 4 days thereafter a plateau indicated the culmination of biofilm formation. Based on these observations further experiments were always conducted in nutrient broth for four days of incubation. The cell density of P. aeruginosa YU-V10 at which the biofilm dynamics were determined was standardized based on the 0.5 McFarland which corresponds to 0.5 optical density. All the experiments were carried out at OD value 0.5 at 630 nm that corresponds to 1×106 CFU/ml.

Further studies to determine the efficacy of BSNPs as antibiofilm agent was done by using the P. aeruginosa YU-V10 culture, that had cell density of 1×106 CFU/ml and was incubated at 370C for 96 hrs.

The test organism on which the antibiofilm agent was aimed to be developed was further characterized for susceptibility of various antibiotics commonly available in the laboratory.

Determination of MIC and MBC for BSNPs on Pseudomonas aeruginosa YU-V10

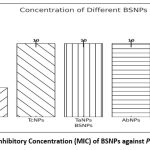

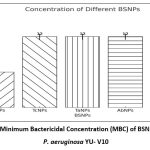

In order to formulate potent antibiofilm agent, the efficacy of BSNPs against the pathogenic P. aeruginosa YU-V10 was determined as Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (MIC) as shown in Figure 2 and Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) as shown in Figure 3 by Resazurin Assay. A comparative analysis of MIC & MBC of medicinal extracts and the BSNPs was carried out in order to determine the difference in their activity potential. The MIC of BSNPs was in range 4µg/ml – 12 µg/ml. The MIC determined against a biofilm forming pathogen can be considered as the Minimum Biofilm Eradication Concentration- MBEC

|

Figure 1: Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of BSNPs against P. aeruginosa YU-V10 |

|

Figure 2: Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) of BSNPs against P. aeruginosa YU- V10 |

Antibiofilm activity of BSNPs

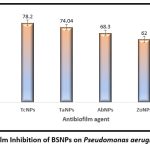

After standardizing the conditions for biofilm growth, the BSNPs were evaluated for antibiofilm activity. Microtiter plate-based experiments in triplicates were performed with predetermined Minimum inhibitory Concentrations. Sub inhibitory concentrations of (Garcinia nanoparticles)GcNPs-2 ,(Trachyspermum ammi nanoparticles) TcNPs- , (Terminalia chebula nanoparticles)TaNPs- 5 , AbNPs- 5 , ZoNPs 6 specific to each BSNPs for which the results have been shown in Figure. Percentage of biofilm inhibition was calculated in comparison with the untreated culture and commercially purchased chemically synthesized AgNPs as control. All five BSNPs were found to be active with more than 60% inhibition, however GcNPs revealed maximum inhibition of 80.7%. The percentage biofilm inhibition of BSNPs is shown in the Figure 4.

The percentage inhibition of biofilm was determined by using the mean absorbance at 630nm and calculated using the formula:

Percentage biofilm inhibition= 100- [(A630nm of test / A630nm control) x 100]

|

Figure 3: Biofilm Inhibition of BSNPs on Pseudomonas aeruginosa YU-V10. |

Development of Antibiofilm Formulation

Effect of GcNPs with extracts by factorial regression analysis

The factorial regression analysis of GcNPs in combination with medicinal extracts was performed to identify statistically significant synergistic effects on biofilm inhibition. Sixteen experimental runs were conducted in triplicates, and mean values with standard deviations were analyzed using ANOVA within the factorial design framework.

Interaction plots indicated synergistic effects particularly between Zingiber officinale and Terminalia chebula, as well as between Terminalia chebula and Trachyspermum ammi. Statistical analysis confirmed these observations: the interaction between GcNPs and Zingiber officinale showed a significant increase in antibiofilm activity with a p-value of 0.037 (95% CI: 0.012–0.084), while the interaction of GcNPs with Terminalia chebula showed a p-value of 0.042 (95% CI: 0.018–0.091). Similarly, the three-way interaction between Zingiber officinale, Terminalia chebula, and Trachyspermum ammi demonstrated enhanced inhibition with a p-value of 0.028 (95% CI: 0.009–0.073).

In contrast, combinations with Agaricus extract did not yield significant effects (p > 0.05), suggesting limited contribution to the observed antibiofilm activity. Confidence intervals around the means for non-significant combinations overlapped substantially with control values, further supporting this interpretation.

Thus, the factorial analysis not only highlighted synergistic combinations but also provided statistical validation of their significance, thereby strengthening the evidence that GcNPs combined with phytocompounds can enhance antibiofilm activity beyond individual effects.

Table 1: Factorial design of Experiment

| StdOrder | Run Order | CenterPt | Blocks | Zingiber | Terminalia | Trachyspermum | Agaricus | Mean + Stand. dev |

| 1 | 14 | 1 | 1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | 0.977 + 0.13 |

| 2 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | 0.503+ 0.11 |

| 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | -1 | 1 | -1 | -1 | 0.132+ 0.03 |

| 4 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | -1 | -1 | 0.521+ 0.20 |

| 5 | 4 | 1 | 1 | -1 | -1 | 1 | -1 | 0.388+ 0.02 |

| 6 | 12 | 1 | 1 | 1 | -1 | 1 | -1 | 0.238+ 0.03 |

| 7 | 7 | 1 | 1 | -1 | 1 | 1 | -1 | 0.617+ 0.06 |

| 8 | 15 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | -1 | 0.408+ 0.05 |

| 9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | 1 | 0.249+ 0.043 |

| 10 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | -1 | -1 | 1 | 0.357+ 0.07 |

| 11 | 16 | 1 | 1 | -1 | 1 | -1 | 1 | 0.310+ 0.04 |

| 12 | 13 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | -1 | 1 | 0.357+ 0.02 |

| 13 | 9 | 1 | 1 | -1 | -1 | 1 | 1 | 0.346+ 0.11 |

| 14 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | -1 | 1 | 1 | 0.304+ 0.04 |

| 15 | 8 | 1 | 1 | -1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.228+ 0.02 |

| 16 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.436+ 0.17 |

|

Figure 4: Factorial regression analysis plots |

Combinations of two BSNPs tested for antibiofilm activity

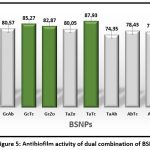

Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm consortium is known to be controlled by multiple virulence factors. For effective control of biofilm, it is essential to inhibit virulence factors involved. In order to increase the spectrum of antibiofilm agent, combinations of BSNPs that have various phytochemical surface activity were evaluated for their combinatorial effect. Dual combinations of BSNPs were derived using checker board method for evaluating their efficacy as depicted in Figure 6. Highest antibiofilm activity (87.93%) was observed for combination of TaNPs and TcNPs (TaTc). All the combinations with GcNPs had enhanced antibiofilm activity greater than 80% with GcTa showing 85.27%.

From the above results of dual combination, GcNPs with TcNPs and ZoNPs, TaTc (TaNPs and TcNPs) were showing high biofilm inhibitions when compared to others. The determination of Fractional Inhibitory Concentration for the combination that has given highest antibiofilm activity has been evaluated using MIC/2, MIC/3, MIC/4. For all the BSNPs MIC/2 values were observed to give maximum of 87.93%, 85.27% and 82.87%. Thereafter the Fractional Inhibitory Index was observed as 1.0 which indicates an additive effect as a result of the combination of BSNPs.

|

Figure 5: Antibiofilm activity of dual combination of BSNPs |

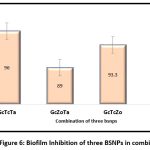

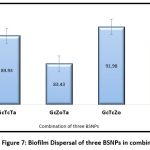

Combinations of three BSNPs tested for antibiofilm activity

For developing high potential antibiofilm agent a combination three nanoparticles were evaluated as shown in the Figure 7 and Figure 8. The results obtained indicate, maximum antibiofilm activity (96%) for GcTcTa combination. A prominent increase in antibiofilm activity was noticed for all the combinations formulated with three AgNPs when compared to two. Overall, there was about 16% enhancement in antibiofilm activity when compared to the individual BSNPs. MIC values of individual BSNPs were used while designing the antibiofilm formulation. Therefore, the combination i.e., BgNFof GcTcTa was used for establishing their anti-virulent property.

|

Figure 6: Biofilm Inhibition of three BSNPs in combination |

|

Figure 7: Biofilm Dispersal of three BSNPs in combination |

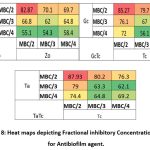

Heat Maps depicting the Fractional Inhibitory Concentrations (FIC) of dual Combinations of BSNPs

In order to standardize the effective concentration for antibiofilm activity, the BSNPs were tested with concentrations MBC/2, MBC/3 and MBC/4 as shown in the Figure 9. Maximum biofilm inhibition was observed in concentrations with MBC/2 for all the combinations. The highest fractional biofilm inhibitory concentration was determined for the GcNPs, ZoNPs, TcNPs and TaNPs as half the concentration (MBC/2) that was evaluated against the P. aeruginosa YU-V10.

|

Figure 8: Heat maps depicting Fractional inhibitory Concentration (FIC) for Antibiofilm agent. |

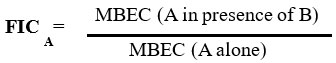

Determination of Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index (FICI)

The FICI of the individual BSNPs in combination as antibiofilm agents were calculated based on the formula:

Where MBEC is the “Minimum Biofilm Eradication Concentration”

FIC Index = FICA + FICB

Table 2: Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index (FICI) of BSNPs

| BSNPs | Fractional Inhibitory Concentration FIC | Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index (FICI) |

| GcNPs | 0.5µg/ml | 1.0 |

| TcNPs | 0.5µg/ml | 1.0 |

| TaNPs | 0.5µg/ml | 1.0 |

Table 3: Combinatorial effect based on FICI

| FIC Index | Combinatorial Effect |

| < 0.5 | Synergism |

| 0.5 to 1.0 | Additive |

| >1 to <2 | Indifference |

| ≥ 2 | Antagonism |

As FICI was observed to be as 1.0, the combinations of BSNPs in the nanoformulation had additive effect while showing the antibiofilm activity. The FICI values are represented in the Tables 2 and Table 3.

Evaluation of BgNF on virulence factors of P. aeruginosa YU-V10

Formulation of GcTcTa BSNPs were therefore referred as biogenic nanoformulation (BgNF) which was identified as a potential combination for Pseudomonas aeruginosa YU-V10 biofilm. The pathogenicity of Pseudomonas is due to virulence factors like EPS, pyocyanin, pyoverdine, pyochelin, and exotoxin A, alkaline protease, elastase, phospholipase, Type IV pili, and flagella that assist the organism in biofilm formation on different surfaces.

Effect of BgNF on EPS production

The key component in development of Pseudomonas biofilm is Exopolysaccharide (EPS) that helps in initial attachment, acts as a protective and an impermeable shield. In the present study virulence factor EPS is targeted because EPS disruption is essential to inhibit the development of biofilm. Reduction in EPS makes the cells susceptible to therapy. Pseudomonas aeruginosa YU-V10 strain in the present study is an established strong biofilm former due to significant EPS production.

Overnight grown culture of Pseudomonas aeruginosa YU-V10 was treated with BgNF(13µg/ml) and incubated for 4 days. EPS was extracted (Forde and Fitzgerald method) from the treated sample and quantified by acid hydrolysis method to determine monosaccharide components (Parker et.al method) using a standard graph of Dextran. The results indicate complete EPS inhibition as shown in Figure 10 with the BgNF when compared with control. The strategy of synergistic combination was evident from the results where individual AgNPs has resulted with GcNPs – 61%, TaNPs- 52%, and TcNPs-95% while 100% inhibition was observed with BgNF. Experimental observations establish EPS as one of its target virulence factors in controlling the Pseudomonas aeruginosa YU-V10 biofilm. The absence of pellicle is shown in the Fig-10

Table 4: EPS production of P. aeruginosa YU-V10 after BgNF treatment.

| Antibiofilm agent | OD at 500nm | Relative EPS concentration in mg/ml |

| Control (untreated) | 0.285+ 0.0005 | 1.686 |

| GcNPs | 0.121+ 0.0005 | 0.651 |

| TaNPs | 0.146+ 0.0005 | 0.809 |

| TcNPs | 0.032+ 0.0005 | 0.089 |

| BgNF (GcTcTa) | -0.024+ 0.0005 | -0.26 |

Values are presented as Mean + Standard deviation.

|

Figure 9: Effect of BgNF on EPS formation. |

Effect of BgNF on Rhamnolipid production

Impact of BgNF was evaluated by treating the overnight grown culture of Pseudomonas aeruginosa YU-V10 and incubating it for 4 days. Culture supernatant was used to extract rhamnolipid into ethyl acetate and quantification was done using Chloroform- methylene blue mixture, by UV- Visible Spectroscopy at 500nm as reported by Tsiry Rasamiravaka et al. Figure-11 shows rhamnolipid extracted and quantified using Chloroform- methylene blue. To understand the impact of synergism, individual AgNPs were also studied along with the BgNF. Fig-11. shows the standard graph plotted for rhamnolipid. From the data generated it was evident that there was powerful impact on the rhamnolipid production after treatment with formulation as well as with individual AgNPs. When compared with control a complete inhibition was shown after quantification as all the values were observed to be negative.

|

Figure 10: Effect of BgNF on Rhamnolipid |

|

Figure 11: Rhamnolipid extracted in organic solvent layer |

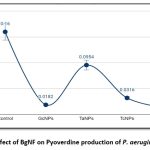

Effect of BgNF on Pyoverdine and Pyochelin Production

Pseudomonas aeruginosa YU-V10 is an established siderophore producer of two types namely Pyoverdine (PVD) and Pyochelin (PCH) which are iron chelators. These siderophores are effective virulence factors enabling proliferation and development of the cells in biofilm formation. Quantification of PVD and PCH was carried out spectroscopically at 380nm and 313nm respectively from 4 days treated culture with individual BSNPs and BgNF The absorbance values were recorded in triplicates and concentrations were determined using Molar Extinction Coefficient (Ɛ) as per the procedure of Francoise Hoegy et al., 201410. Concentration of PVD after treatment with BgNF was 0.012 µg/ml against the control which was 0.16µg/ml. which shows a 100-fold decrease in pyoverdine production as shown in Figure-13. Similarly, production of PCH was observed to have the same trend in reduction after treatment with BgNF as shown Figure-14.

|

Figure 12: Effect of BgNF on Pyoverdine production of P. aeruginosa YU-V10 |

|

Figure 13: Effect of BgNF on Pyochelin production of P. aeruginosa YU-V10 |

Effect of BgNF on Swarming Motility

Biofilm formation requires movement of cells across the surface in order to develop new micro colonies which is aided by motility. Swarming of Pseudomonas aeruginosa YU-V10 is a movement on the semi-solid surface which is characterized by biosurfactants and motility mediated by flagella. Since it is also a major pathogenic feature, impact of BgNF has been evaluated by plate-based assay on swarming agar as shown in Figure-15; Figure-16 shows the mean + Standard deviation plots, wherein it indicates that there is a 66% reduction in swarming after treatment with BgNF when compared to the control. Though there was reduction with the individual BSNPs, BgNF showed a prominent additive effect which is evident from these results.

|

Figure 14: Swarming nature of P. aeruginosa YU-V10 after BgNF treatment |

|

Figure 15: Effect of BgNF treatment on Swarming motility of YU-V10 |

Detection of signal molecules by UPLC-MS analysis

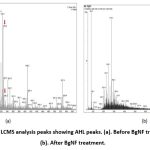

The supernatants of P. aeruginosa YU-V10 after treatment with BgNF were subjected to extraction of AHLs. The presence of signal molecules was analysed by UPLC-MS analysis. The analysis was done in conditions -column: ACQUITY UPLC CSH C-18 (2.1*100) mm1.7µm; Mobile phase-A: Water; Mobile Phase-B: Acetonitrile (100%), Flow rate :0.4 ml/min, sample volume :10µl. The data generated was analysed with the standard chart of AHL with protonated mass to detect the presence of different types of signal molecules. The presence of signal molecules has been indicated by red coloured arrows in figures showing signal molecule peaks represented in the chromatogram generated by UPLC-MS analysis. Standards used in the above analysis were C6-HSL & C12-HSL which have shown sharp peaks with protonated mass 200.0 and 284.2 respectively as represented in the literature.

From the results obtained P. aeruginosa YU-V10 culture during analysis was found to show signal molecules OXO-C6-HSL; OXO-C8-HSL; OH-C8-HSL; OH-C10-HSL; OH-C14:1-HSL; and OH-C14-HSL before BgNF treatment as evident in the Fig – 17(a), whereas none of the signal molecules were observed after antibiofilm treatment as shown in the Fig-17 (b).

|

Figure 16: LCMS analysis peaks showing AHL peaks. (a). Before BgNF treatment (b). After BgNF treatment. |

Discussion

Following confirmation of quorum quenching (QQ) and anti-virulent activity of BSNPs against Chromobacterium violaceum 4212, their efficacy was extended to Pseudomonas aeruginosa YU-V10, a multidrug-resistant urinary catheter isolate and widely used biofilm model. Biofilm kinetics revealed maximum maturation at four days in nutrient broth, which was standardized for further testing.12,13

Among the BSNPs, GcNPs displayed the strongest inhibition (80.7% at 3 µg/ml), while the others showed moderate activity (>60%). Notably, combining BSNPs with edible extracts enhanced efficacy, with synergistic interactions observed for Terminalia chebula–Zingiber officinale and T. chebula–Trachyspermum ammi. Such synergy is consistent with earlier studies where phytochemicals enhanced the penetration and action of nanomaterials against resilient biofilms. The triple combination (GcTcTa), formulated as BgNF, achieved remarkable inhibition (96%) and dispersal (~90%), surpassing previous nanoparticle-based antibiofilm reports that often remained below 80% efficacy.14

Beyond biofilm inhibition, BgNF strongly attenuated virulence-associated traits by completely abolishing EPS and pellicle formation, reducing rhamnolipids (100%), pyoverdine (92.5%), and pyochelin (92.12%), and suppressing swarming motility (~70%). These findings align with reports highlighting the central role of quorum-regulated virulence factors in biofilm resilience. UPLC-MS analysis confirmed total suppression of AHL signals, supporting BgNF’s role as a quorum quenching formulation likely acting through interference with LasR, RhlR, and PqsR regulators.15,16,17

Overall, BgNF demonstrates superior antibiofilm and antivirulence activity against multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa through synergistic nanoparticle–phytocompound interactions. 18,19 Compared with earlier single-agent or nanoparticle-only approaches, this strategy offers a promising, multi-targeted intervention for controlling device-associated infections.20,21

Conclusion

This study developed a biogenic nanoparticle formulation (BgNF) with strong antibiofilm and anti-virulent activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa YU-V10, a multidrug-resistant urinary catheter pathogen. BgNF inhibited biofilm formation by 96%, disrupted established biofilms by ~90%, and markedly reduced virulence determinants including EPS, rhamnolipids, siderophores, and swarming motility. UPLC-MS analysis confirmed its quorum quenching potential through suppression of AHL signals. These findings highlight BgNF as a potent, multi-targeted strategy for combating biofilm-associated infections and mitigating antimicrobial resistance.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their heartfelt gratitude to the Management and Principal of Bhavan’s Vivekananda College of Science, Humanities and Commerce for their unwavering support and guidance throughout this research. We are especially thankful for providing access to laboratory resources, facilitating the necessary infrastructure, and encouraging an environment conducive to scientific inquiry and growth. Their commitment to excellence in education and research has been instrumental in the successful completion of this study.

Funding Sources

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

This statement does not apply to this article.

Ethics Statement

This research did not involve human participants, animal subjects, or any material that requires ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not involve human participants, and therefore, informed consent was not required.

Clinical Trial Registration

This research does not involve any clinical trials.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

Not Applicable

Author Contributions

Sarada Jonnalagadda: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision

Anju Sivasankaran: Data Collection, Analysis, Writing

References

- McDougald D, Klebensberger J, Tolker‑Nielsen T, Webb JS, Conibear T, Rice SA, Kjelleberg S. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a model for biofilm formation. In: Pseudomonas: Model Organism, Pathogen, Cell Factory. Wiley‑VCH; 2008:215‑253. doi:10.1002/9783527622009.ch9

CrossRef - Roy V, Meyer MT, Smith JA, Gamby S, Sintim HO, Ghodssi R, Bentley WE. AI‑2 analogs and antibiotics: a synergistic approach to reduce bacterial biofilms. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97(6):2627‑2638. doi:10.1007/s00253‑012‑4404‑6

CrossRef - Alhede M, Bjarnsholt T, Givskov M, Alhede M. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms: mechanisms of immune evasion. Adv Appl Microbiol. 2014;86:1‑40. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-800262-9.00001-9

CrossRef - Algburi A, Comito N, Kashtanov D, Dicks LM, Chikindas ML. Control of biofilm formation: antibiotics and beyond. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2017;83(3):e02508‑16. doi:10.1128/AEM.02508‑16

CrossRef - Ong KS, Mawang CI, Daniel‑Jambun D, Lim YY, Lee SM. Current anti‑biofilm strategies and potential of antioxidants in biofilm control. Expert Rev Anti‑Infect Ther. 2018;16(11):855–864. doi:10.1080/14787210.2018.1535898

CrossRef - Brackman G, Coenye T. Quorum sensing inhibitors as anti‑biofilm agents. Curr Pharm Des. 2015;21(1):5–11. doi:10.2174/1381612820666140905114627

CrossRef - Loo YY, Radu S, Aoki M, et al. Resazurin-based microdilution method for assessing minimum inhibitory concentration and biofilm eradication of silver-based nanoparticles against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Microbiol Methods. 2018; 153:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2018.10.011

CrossRef - Forde A, Fitzgerald GF. Analysis of exopolysaccharide (EPS) production mediated by the bacteriophage adsorption blocking plasmid, pCI658, isolated from Lactococcus lactis cremoris HO₂. Int Dairy J. 1999;9(7):465–472. doi:10.1016/S0958-6946(99)00115-6

CrossRef - Rasamiravaka T, Vandeputte OM, El Jaziri M. Procedure for rhamnolipids quantification using methylene‑blue. Bio‑protocol. 2016;6(7): e1783. doi:10.21769/BioProtoc.1783

CrossRef - Hoegy F, Mislin GL, Schalk IJ. Pyoverdine and pyochelin measurements. In: Pseudomonas Methods and Protocols. Humana Press; 2014:293‑301. doi:10.1007/978‑1‑4939‑0473‑0_17.

CrossRef - Moradhaseli S, Mirakabadi AZ, Sarzaeem A, Kamalzadeh M, Hosseini RH. Cytotoxicity of ICD‑85 NPs on human cervical carcinoma HeLa cells through caspase‑8 mediated pathway. Iran J Pharm Res. 2013;12(1):155–163. doi:10.22037/ijpr.2013.1253

- Qin, S., Xiao, W., Zhou, C., Pu, Q., Deng, X., Lan, L., Liang, H., Song, X., & Wu, M. (2022). Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Pathogenesis, virulence factors, antibiotic resistance, interaction with host, technology advances and emerging therapeutics. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 7, 199. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-022-01047-2.

CrossRef - Saeki EK, Yamada AY, De Araujo LA, et al. Subinhibitory concentrations of biogenic silver nanoparticles affect motility and biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021; 11:253. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2021.632543

CrossRef - Habash MB, Park AJ, Vis EC, Harris RJ, Khursigara CM. Synergy of silver nanoparticles and aztreonam against Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 biofilms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(10):5818‑5830. doi:10.1128/AAC.03133‑14

CrossRef - Barapatre A, Aadil KR, Jha H. Synergistic antibacterial and antibiofilm activity of silver nanoparticles biosynthesized by lignin‑degrading fungus. Bioresour Bioprocess. 2016;3(1):1‑13. doi:10.1186/s40643‑016‑0092‑9

CrossRef - Deziel E, Lepine F, Milot S, Villemur R. rhlA is required for the production of a novel biosurfactant promoting swarming motility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: 3‑(3‑hydroxyalkanoyloxy) alkanoic acids (HAAs), the precursors of rhamnolipids. Microbiology. 2003;149(8):2005‑2013. doi:10.1099/mic.0.26482‑0

CrossRef - Wood TL, Gong T, Zhu L, Miller J, Miller DS, Yin B, Wood TK. Rhamnolipids from Pseudomonas aeruginosa disperse the biofilms of sulfate‑reducing bacteria. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2018;4(1):1‑8. doi:10.1038/s41522‑018‑0066‑2

CrossRef - Singh BR, Singh BN, Singh A, Khan W, Naqvi AH, Singh HB. Mycofabricated biosilver nanoparticles interrupt Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing systems. Sci Rep. 2015;5(1):1‑14. doi:10.1038/srep10362

CrossRef - Banin E, Vasil ML, Greenberg EP. Iron and Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(31):11076‑11081. doi:10.1073/pnas.0505291102

CrossRef - Cornelis P, Dingemans J. Pseudomonas aeruginosa adapts its iron uptake strategies in function of the type of infections. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2013;3:75. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2013.00075

CrossRef - Hentzer M, Wu H, Andersen JB, et al. Attenuation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence by quorum sensing inhibitors. EMBO J. 2003;22(15):3803‑3815. doi:10.1093/emboj/cdg366

CrossRef

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.