Manuscript accepted on : 27-08-2025

Published online on: 17-09-2025

Plagiarism Check: Yes

Reviewed by: Dr. Y. Indira Muzib

Second Review by: Dr. Seyedeh Maryam Mousavi

Final Approval by: Dr. Jagdish Chandra Joshi

Natural Antihypertensive Peptides: Emerging Therapeutics for Blood Pressure Management

Ashvini Trambak Varungase1,2* , Nirmala Vikram Shinde1

, Nirmala Vikram Shinde1

1Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, S.M.B.T. College of Pharmacy, Nashik, India.

2Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, Amrutvahini College of Pharmacy, Maharashtra, India.

Corresponding Author E-mail:atvarungase@gmail.com

ABSTRACT: Hypertension, a primary risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, continues to be a significant global public health challenge. In the pursuit of effective, secure, and sustainable antihypertensive treatments, there has been an increasing emphasis on natural sources, particularly bioactive peptides derived from proteins found in various foods, including milk, fish, and meat. This review delves into advanced bioanalytical methodologies used to quantify and evaluate the pharmacokinetics of emerging antihypertensive peptides obtained from these natural sources. Moreover, this review explores the potential contributions of nanotechnology and bioinformatics in enhancing the delivery and bioavailability of antihypertensive peptides, with the prospect of fostering the development of functional foods and nutraceuticals. Additionally, we underscore the role of biotechnology in facilitating the large-scale production of these peptides while addressing concerns pertaining to their stability and safety. In conclusion, the application of advanced bioanalytical techniques, coupled with a deeper comprehension of pharmacokinetics, offers a promising pathway to unlock the full potential of antihypertensive peptides sourced from natural origins. Ultimately, this endeavour holds the potential to make significant contributions to the management and prevention of hypertension and associated cardiovascular diseases.

KEYWORDS: Antihypertensive Peptides; Advanced Quantification; Hypertension; Natural Sources; Pharmacokinetic parameters

| Copy the following to cite this article: Varungase A. T, Shinde N. V. Natural Antihypertensive Peptides: Emerging Therapeutics for Blood Pressure Management. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(3). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Varungase A. T, Shinde N. V. Natural Antihypertensive Peptides: Emerging Therapeutics for Blood Pressure Management. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(3). Available from: https://bit.ly/42uFwW8 |

Introduction

Hypertension is a medical condition characterized by systolic and diastolic blood pressure (BP) levels of 140/90 mmHg or higher in adults. The global prevalence of hypertension, or sustained high BP, is a matter of concern. Despite numerous initiatives to reduce these figures, the statistics have shown minimal improvement from 2010 to the present day. This lack of progress can be linked to an increase in alcohol, tobacco, and substance use, as well as a rising prevalence of obesity, all of which are significant risk factors for hypertension.1

Hypertension and its associated health issues are a leading cause of mortality in the context of non-communicable diseases. Even with the existence of effective antihypertensive medications, some individuals with hypertension do not achieve the desired reduction in BP. Furthermore, the considerable cost and potential adverse effects, like heightened serum potassium levels and decreased BP, associated with these drugs, result in insufficient compliance with treatment. This, in turn, increases the vulnerability to other chronic ailments arising from poorly controlled hypertension, e.g., organ dysfunction and stroke.2 This drives the ongoing pursuit of safer agents that can effectively normalize BP, providing hope for individuals who do not respond favorably to presently available antihypertensive medications.

In traditional medicine, the use of natural products derived from plants3 and food proteins4 has been a longstanding approach in the management of hypertension. Plant extracts rich in polyphenols have shown antihypertensive effects in both normotensive and hypertensive rodents.5 Clinical trials also suggest that high-protein diets can influence hypertension risk. In the POUNT Lost Trials, high-protein intake reduced genetic susceptibility to hypertension.6 Conversely, a 5-year study of over 13,000 Korean men found that animal-based proteins were linked to a higher hypertension risk than plant-based proteins.7

A study in the Iranian population found that protein-based diets are linked to a lower risk of hypertension.8 Protein-derived peptides, after intestinal hydrolysis, interact with muscarinic and Angiotensin-II receptors, inhibit renin and ACE activity, and modulate the RAS pathway, contributing to BP reduction.9 Dietary proteins also target hypertension-related factors like oxidative stress, obesity, and diabetes by increasing nitric oxide, reducing advanced glycation end-products, and improving insulin sensitivity.10

Food proteins, their hydrolysates, and peptides are key sources of antihypertensive agents. 11 Hydrolysis exposes specific amino acid side chains, enhancing peptide bioactivity. Notably, buffalo and cow milk proteins hydrolyzed with enzymes like papain, pepsin, and trypsin show stronger ACE-inhibitory effects than their native forms.12

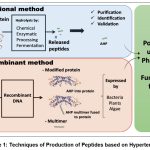

Biologically active compounds known as Active Hypotensive Peptides (AHPs) exhibit effects similar to those of antihypertensive medications. These peptides are naturally embedded within proteins from numerous sources and may offer additional health advantages, e.g., serving as a valuable source of essential amino acids, thereby enhancing their nutritional value.13Diverse techniques are available for the extraction of AHPs and other biopeptides as presented in fig 1 given below: a) Cooking: AHPs and biopeptides can be liberated from protein-rich foods through the process of cooking; b) Chemical Hydrolysis: A chemical approach can be utilized to enzymatically hydrolyze proteins, releasing AHPs; c) Protease Hydrolysis: Enzymes like alcalase, trypsin, pepsin, and flavor enzyme are employed to break down proteins and produce AHPs; d) Fermentation: AHPs and biopeptides can be derived from the fermentation of protein-rich substances using numerous microorganisms, including Lactobacillus and Saccharomyces cerevisiae; e) Recombinant Methods: AHPs can also be generated through recombinant methods. This may include engineering tandem multimers of bioactive peptides by attaching them to carrier proteins or integrating them into food-based proteins such as β-conglycinin, amaranth 11S globulin, or rice glutelins 14

|

Figure 1: Techniques of Production of Peptides based on Hypertension. |

Active Hypotensive Peptides (AHPs) have been the subject of very few reports in the pharmaceutical literature, with only a small number of investigations involving clinical human trials. Most of these studies, however, have focused on the well-studied tripeptides IPP and VPP, which are frequently present in milk,15 as well as the sardine-derived VY dipeptide.16These milk-fermented tripeptides, IPP (Ile-Pro-Pro) and VPP (Val-Pro-Pro), decreased systolic and diastolic blood pressure by 5.0 and 2.3 mm Hg, respectively, when given in doses ranging from 5 to 1000 mg daily.15 Commercial products such as PeptACETM (LKPNM) and AmealBP® (IPP, VPP) now contain these AHPs.15

AHPs in functional foods mainly come from milk, sardines, and bonito. Products include IPP/VPP-fermented milk (Evolus®, Finland), LKPNM soup (Nippon Supplement, Japan), and FV/VY/IY-rich wakame jelly (Riken Vitamin, Japan). Supplements like C12 Peption (DMV International, Netherlands) contain sequences such as FFVAPFPEVFGK. Alternative delivery methods involve AHPs released via gastrointestinal digestion of modified proteins or engineered multimeric proteins in seeds, lactic acid bacteria, or microalgae.14

Methodology

This review is based on a comprehensive selection of relevant peer-reviewed articles sourced from databases such as PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

Literature Review

Hypertension and Antihypertensive Peptides (AHP)

Cardiovascular diseases cause around 17 million deaths annually, with hypertension affecting nearly 1 billion people, responsible for up to 9 million of these deaths.17In Canada, nearly 6 million individuals, or about one in five adults, have hypertension.18 Hypertension is often called the silent killer, as it frequently lacks early symptoms and is inadequately managed even when diagnosed early.19 However, it significantly increases the risk of atherosclerosis and related conditions, e.g., CHD, cerebrovascular disease, and renal disease.20 Addressing hypertension has significant health and socioeconomic implications. In the USA, the cost of treating hypertension and its associated conditions reached $156 billion in 2011.21, 22Many antihypertensive drugs have noticeable side effects, e.g., headaches and dry cough, and patients often have poorly controlled BP despite treatment, increasing the risk of complications.22,23Therefore, there’s an urgent need for innovative, cost-effective strategies to enhance hypertension management.Diet plays a key role in health, influencing conditions like cardiovascular disease, obesity, and diabetes.24 The DASH study showed that diets rich in fruits and vegetables help lower BP.25 Nutrients like sodium and potassium significantly impact BP and vascular health,29 while macronutrients protein, fat, and carbohydrates also play a crucial role in hypertension management.

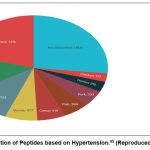

The OmniHeart trials showed that replacing carbs with protein or monounsaturated fats can lower BP and heart disease risk.27 Food proteins contain bioactive peptides released through digestion, fermentation, or processing, offering benefits beyond nutrition.28 Antihypertensive peptides, especially ACE inhibitors, are promising for managing hypertension 29, 30. Some also show antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and opioid-like effects,31 though in vitro and in vivo results often differ.32To develop effective antihypertensive peptides, a comprehensive understanding of hypertension’s pathophysiology and potential targets is vital. While previous reviews have explored mechanisms of action for many food-derived antihypertensive peptides,33 limited information exists on their multifaceted roles in pathways contributing to persistent hypertension. An image (Fig. 2) has been provided highlighting the distribution of antihypertensive peptides in the “AHTPDB database (http://crdd.osdd.net/raghava/ahtpdb/) ” based on numerous sources.

|

Figure 2: Dissemination of Peptides based on Hypertension.95 (Reproduced from cited Sources) |

Hypertension arises from complex genetic and environmental factors, with over 90% of cases having no clear cause.34 Key contributors include high sympathetic activity, excess sodium and low potassium/calcium intake, altered renin secretion, increased ACE and Ang II levels, reduced nitric oxide, and vascular inflammation.35 RAS hyperactivity, endothelial dysfunction, sympathetic overactivation, and vascular abnormalities are central to its progression.36

Production of Antihypertensive Peptides-Food Origin

Clinical trials are essential to assess the efficiency and pharmacokinetics of antihypertensive bioactive peptides. VPP and IPP have shown significant BP reductions in hypertension populations when administered orally in foods like fermented milk and fruit juice in studies from Japan and Finland.37,38However, when these same peptides were orally administered to hypertensive individuals in the Netherlands and Denmark, they did not achieve a similar reduction in BP. This observation suggests potential variations in efficiencybetweendiverse human populations.39

A meta-analysis of 18 clinical trials confirms that oral VPP and IPP peptides effectively reduce BP in hypertensive individuals, with the most pronounced effects observed in Asian subjects.40Boelsma et al. showed that oral IPP significantly reduced BP in Caucasian individuals with stage-1 hypertension.41An Alternative study found that milk tripeptides combined with plant sterols lowered systolic BP, total cholesterol, and LDL cholesterol in hypertensive, hypercholesterolemic patients. 42BP reductions of up to 13/8 mm Hg occur within 1–2 weeks at 3–55 mg/day.

Low doses (2–10.2 mg/day) of VPP and IPP reduced SBP by 4.0 and DBP by 1.9 mm Hg in mildly hypertensive patients 43 Hirota et al. showed these peptides also improved endothelial function.44 Yoghurt enriched with other casein peptides (RYLGY, AYFYPEL) lowered SBP by 12 mm Hg over 6 weeks.45 Pea protein hydrolysate reduced SBP by 5–7 mm Hg in a small trial, though conclusions are limited because of sample size (n=7).46 Clinical trials with the sardine-derived dipeptide VY showed mixed results: one small study reported SBP and DBP reductions of 9.3 and 5.2 mm Hg after 4 weeks,47 while another larger trial found significant BP lowering without side effects.49 However, a single dose increased plasma VY but did not acutely lower BP, suggesting longer treatment may be needed.50 The clinical impact remains uncertain because of small, varied samples.48

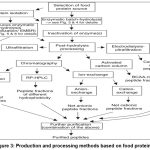

Numerous animal studies have indicated substantial reductions in BP, typically ranging from 20 to 40 mmHg, following the administration of bioactive peptides derived from food proteins.51 In contrast, human studies have reported more modest reductions, generally falling within the range of 2 to 12 mmHg.52 It is worth considering that most animal studies focused on specific hypertension models, e.g., spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR), where all subjects share a common underlying pathophysiology. Conversely, human participants in clinical studies are likely to exhibit diverse etiologies contributing to their hypertension. Animal studies often use specific strains, while human trials include diverse racial and genetic backgrounds, affecting bioactive peptide efficacy.53 Differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics between rodents and humans add complexity. More clinical research across varied ethnic groups is needed to confirm their antihypertensive benefits. A diagram of production and processing methods is shown in Fig. 3.

|

Figure 3: Production and processing methods based on food protein.96 |

Production of Antihypertensive Peptides-Animal Origin

There is an emergentimportance in the potential applications of bioactive molecules in the fields of nutrition and healthcare.54 Meat, being a rich source of protein, has received significant attention for its ability to produce bioactive peptides, especially those with ACE-inhibitory properties. Implementing food-based approaches to manage hypertension offers a promising avenue to enhance overall health, promote well-being, and reduce healthcare costs. ACE-inhibitory peptides have been identified in proteolytic products of animal, plant, and microbial proteins.55 Enzymatic hydrolysis of muscle proteins like myosin and collagen also yields bioactive peptides.56 Many studies confirm their in vitro ACE inhibition and BP-lowering effects in animals, with supportive evidence in humans.55Arihara et al. identified two ACE-inhibitory peptides from thermolysin-treated porcine muscle that lowered BP in hypertensive rats.57 Saiga et al. found three potent ACE-inhibitory peptides from chicken breast hydrolysates, with Gly-Phe-Hyp-Gly-Thr-Hyp-Gly-Leu-Hyp-Gly-Phe being the most effective.58

Fu-Yuan and their team described the maximum ACE inhibitory action in the hydrolysate acquired from chicken leg bones when using the alkalase enzyme for the hydrolysis process.61 In separate studies, Jang and Lee, as well as Kazunori and their collaborators, identified powerful ACE inhibitory peptides. Jang and Lee isolated Val-Leu-Ala-Gln-Tyr-Lys from beef protein, and Kazunori et al. identified RMLGQTPT from porcine troponin C; both showed strong ACE inhibition 59,60

Arihara et al. identified two ACE-inhibitory pentapeptides (myopentapeptides A and B: ITTNP) from thermolysin-digested porcine myosin.62 Katayama et al. reported an octapeptide VKKVLGNP from pepsin-digested myosin light chain,63 and a novel antihypertensive peptide M6 (KRVITY) from porcine myosin B hydrolysate.64 Katayama et al. identified ACE-inhibitory peptides KRQKYDI from porcine troponin T,65 VKKVLGNP from myosin light chain,63 and KRVITY (peptide M6) from myosin B of porcine skeletal muscle.64

ACE-inhibitory peptides have been found in soluble protein hydrolysates of fish like shellfish, tuna, bonito, salmon, and sardine.66 Sardine viscera enzymes hydrolyzed sardinelle proteins, yielding low-hydrophobicity peptides (200–600 Da).67 The sardine-derived dipeptide valyl-tyrosine lowered BP by 7.4–9.7 (SBP) and 4.5–5.2 mm Hg (DBP) in humans.67 Similar ACE inhibitory activity was found in Pacific Hake after digestion.68 Fish-derived peptides show promise in pharmaceuticals, e.g., BP-lowering capsules containing Katsuobushi oligopeptide LKPNM from thermolysin-treated dried bonito. This peptide is activated to LKP by digestion. Examples include Vasotensin 120T™ and PeptACE™ Peptides 90.69. About 30% of blood from slaughtered animals is used in the food industry, 70%, but safety concerns, religious restrictions, and consumer aversion limit its use. 71,72 Innovative approaches are needed to better utilize blood components, reducing environmental hazards and tapping into this resource’s potential.72,73

Studies highlight blood components as promising sources of bioactive peptides, offering value-added use for slaughterhouse blood.74Several studies, primarily centred on bovine and porcine blood and conducted over the past decade, have demonstrated the ACE-inhibitory activity of bioactive peptides obtained from blood sources. Food-derived peptides, including blood proteins, inhibit ACE and are milder and safer than synthetic drugs.75 Moreover, natural peptides with ACE-inhibitory properties often possess additional bioactive functions and are easily absorbed.76

Table 1: Bioactive peptides from numerous animal proteins with antihypertensive action (Bhat et al., 2017)

| Protein source | Peptide/sequence |

| Casein | Phe-Phe-Val-Ala-Pro |

| Val-Pro-Pro | |

| Ile-Pro-Pro | |

| Whey proteins | Tyr-Pro |

| Porcine skeletal muscle | Ile-Thr-Thr-Asn-Pro |

| Thr-Asn-Pro | |

| Met-Asn-Pro-Pro-Lys | |

| Ile-Thr-Thr-Asn-Pro | |

| RMLGQTPT | |

| Chicken | Ile-Lys-Trp |

| Leu-Lys-Pro | |

| Gly-Phe-Hyp-Gly-Thr-Hyp-Gly-Leu- | |

|

Hyp-Gly-Phe |

|

| Beef | Leu-Ala-Gln-Tyr-Lys |

Production of Antihypertensive Peptides-Dairy Origin

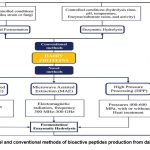

Epidemiological studies link lower milk and protein intake to higher hypertension risk.77-80 Garcia-Palmieri et al. found Puerto Rican men who avoided milk had twice the hypertension incidence.78 Clinical trials further confirm that ACE-inhibitory peptides reduce BP in humans. Milk protein-derived peptides have demonstrated BP-lowering effects in animal models and may benefit vascular health. Though clinical evidence on lactotripeptides is still debated, they provide a valuable non-pharmacological option for managing hypertension(Fig. 4). .81Milk-derived ACE inhibitory peptides may be less potent than drugs but are promising, safe, natural agents without side effects. Their effectiveness depends on resistance to degradation by intestinal and plasma peptidases to reach target sites intact.82

Bioactive peptides are commonly produced via milk fermentation using traditional dairy starter cultures. Within the end-products, which encompass numerous cheese varieties and fermented kinds of milk, one can find peptides with antihypertensive properties.83 As a result, when these traditional dairy products are incorporated into one’s daily diet, they may confer specific health benefits under certain conditions. Multiple studies have documented the identification and isolation of antihypertensive peptides in numerous cheese varieties. It’s important to note that the stability of these peptides, which encompass those with ACE-inhibitory activity,84 β-casomorphin,85 and calcium-binding phosphopeptides,86 is influenced by factors, e.g., pH, salt concentration, and the types of enzymes present during the cheese ripening process.

Muehlenkamp and Warthesen reported β-casomorphin degradation in cheddar cheese,87 while Gomez-Ruiz et al.84 found peptides retained ACE-inhibitory activity after simulated digestion. Hernández-Ledesma et al.88 reported moderate ACE-inhibitory activity in fermented milk and fresh cheeses, which stayed stable or increased after enzymatic digestion. Hernández-Ledesma et al.89 found infant formulas exhibit ACE-inhibitory activity. Overall, digestion may enhance bioactive peptide release from dairy proteins, with some peptides resisting digestion 90,91

While the discovery of novel antihypertensive peptides from natural sources has garnered significant attention, their successful therapeutic application hinges on robust bioanalytical and pharmacokinetic evaluation. However, the current literature often overlooks key challenges and methodologies essential for this translation. One critical omission is the detailed discussion of LC-MS/MS quantification strategies, which remain the cornerstone for the accurate detection and quantification of low-abundance peptides in complex biological matrices due to their high sensitivity and selectivity. The bioanalytical evaluation of antihypertensive peptides using LC-MS/MS techniques has become increasingly important due to its high sensitivity and selectivity.92 These methods face challenges such as signal splitting from multiple charge states, unfavorable fragmentation patterns, and adsorption issues during sample preparation.93 Strategies to maximize sensitivity and improve quantification limits include optimizing mass spectrometry parameters, chromatography conditions, and sample preparation techniques.94 Recent advancements in LC-MS technology have enabled the development of highly sensitive methods with lower limits of quantitation in the picomolar range, supporting pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies. While LC-MS offers advantages over traditional immunoassays, there is still a need for harmonization of regulatory guidelines and further research on matrix effects and co-medications.95 The integration of artificial intelligence in LC-MS shows promise for revolutionizing bioanalytical methods.95

Furthermore, naturally derived peptides suffer from poor oral bioavailability owing to gastrointestinal degradation, enzymatic hydrolysis, and limited intestinal permeability. These barriers severely limit systemic exposure and must be addressed through formulation and delivery innovations. Oral delivery of peptide drugs faces significant challenges due to poor bioavailability caused by gastrointestinal degradation and limited intestinal permeability.96,97 These barriers result in oral bioavailability typically under 1% for peptides. To overcome these obstacles, various strategies have been explored, including chemical modifications, incorporation of unnatural amino acids, cyclization, and pro-drug approaches.98 Advanced delivery systems such as nanoparticles and microemulsions show promise in improving oral peptide bioavailability. Additionally, the use of permeation enhancers has gained renewed interest to increase gut permeability and enhance absorption.99 Despite decades of research, clinical success remains elusive due to challenges in achieving reproducible efficacy and addressing safety concerns. However, recent advancements in formulation strategies and delivery technologies offer hope for the development of effective oral peptide delivery systems.

The phenomenon of first-pass metabolism, primarily involving hepatic degradation, also significantly impacts peptide pharmacokinetics but is often underreported in early-stage evaluations. The pharmacokinetics of peptide and protein therapeutics are complex, involving various absorption, distribution, and elimination processes.100 First-pass metabolism, particularly in the liver, significantly impacts peptide pharmacokinetics.101 Biotransformation studies are crucial for understanding the in vivo stability and potency of biotherapeutics, especially those containing non-native chemical linkers.102 These studies should be implemented early in development to select stable candidates and appropriate bioanalytical techniques. Renal and hepatic impairment can affect the pharmacokinetics of therapeutic peptides and proteins, often necessitating dose adjustments or risk mitigation strategies.103 The increasing structural diversity of these therapeutics, including the use of non-natural amino acids and conjugation technologies, suggests a need for reassessing the impact of organ impairment on their pharmacokinetics. Advanced bioanalytical techniques, including mass spectrometry, are essential for efficient and reliable detection of peptide and protein drugs.

In addition, transporter-mediated uptake mechanisms, such as those involving hPEPT1 and OATP1A2, play a crucial role in the intestinal absorption and tissue distribution of bioactive peptides, offering potential targets to enhance peptide delivery. Peptide transporters play a crucial role in the absorption of dietary proteins and peptide-like drugs in the intestine and kidneys. Two main transporters, PEPT1 and PEPT2, have been identified and characterized.104,105 PEPT1, located in the intestinal brush border membrane, is particularly important for the oral bioavailability of various drugs, including β-lactam antibiotics and antiviral prodrugs.106 In addition to peptide transporters, organic anion transporting polypeptides (OATPs), such as OATP1A2 and OATP2B1, have been implicated in intestinal drug absorption. These transporters exhibit broader substrate selectivity compared to PEPT1, offering potential for enhanced oral drug delivery. Understanding the structure, function, and regulation of these transporters is crucial for developing novel drug delivery systems and improving the bioavailability of peptide-based therapeutics.

|

Figure 4: Novel and conventional methods of bioactive peptides production from dairy proteins.97 |

Discussion

The worldwide prevalence of hypertension, a major risk factor for cardiovascular disorders, has attracted a lot of interest in the investigation of natural antihypertensive peptides. Millions of people worldwide suffer from hypertension, which is linked to significant morbidity, mortality, and medical expenses. Even if traditional pharmaceutical treatments, including beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors, successfully reduce blood pressure, prolonged usage of these medications can result in negative side effects, excessive expenses, and non-compliance from patients. Because of this, scientists are now looking into more natural, alternative approaches, especially dietary changes and bioactive peptides that may lower blood pressure.

One of the best-established non-pharmacological strategies for managing hypertension is the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet. Adherence to the DASH diet, which is low in saturated fat and cholesterol and high in fruits and vegetables and low in dairy, has been shown to dramatically lower both systolic and diastolic blood pressure25. The consumption of naturally occurring bioactive peptides and minerals that regulate vascular function and electrolyte balance is partly responsible for the positive effects of such dietary patterns.

The response of blood pressure to dietary treatments is significantly influenced by genetic predisposition in addition to dietary patterns. Studies have indicated that specific genetic variants impact salt sensitivity, which in turn impacts an individual’s hypertensive response to sodium intake in the diet26. This highlights the significance of genetic screening and customized nutrition in creating successful hypertension treatments, while also emphasizing that the effectiveness of bioactive peptide interventions may vary based on a person’s genetic composition.

Furthermore, it is becoming more well acknowledged that natural protein sources have the capacity to produce peptides that lower blood pressure. For example, bovine blood plasma, which is frequently regarded as a by-product of slaughterhouses, has been used as an economical substrate for the manufacture of probiotics, proving both its economic worth and the viability of producing bioactive peptides with health-promoting qualities70. These methods highlight the benefits of using waste materials and producing useful bioactive substances that can control blood pressure.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the review underscores the imperative need to explore and harness the potential of antihypertensive peptides derived from natural sources. The thorough examination of bioanalytical methods and pharmacokinetic evaluation techniques within this review significantly enhances our comprehension of the efficacy and safety of these peptides. The implications of this research are extensive, opening the door to innovative non-pharmacological strategies for managing hypertension. As a recommendation for future research, we advocate for ongoing exploration of bioactive peptides, with a specific emphasis on optimization, diverse delivery methods, and the evaluation of their long-term health implications. Such efforts will further propel the practical utilization of these peptides in hypertension management and contribute to the enhancement of public health.

Acknowledgement

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to all those who have supported and contributed to the development of this review on advanced bioanalytical approaches for the quantification and pharmacokinetic evaluation of novel antihypertensive peptides derived from natural sources.

This review is dedicated to the global scientific community working towards innovative approaches for hypertension management, and to those who continue to inspire progress in the field of bioanalytical science.

Funding Sources

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

This statement does not apply to this article.

Ethics Statement

This research did not involve human participants, animal subjects, or any material that requires ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not involve human participants, and therefore, informed consent was not required.

Clinical Trial Registration

This research does not involve any clinical trials.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

Not Applicable

Author Contributions

Ashvini Trambak Varungase: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Original Draft. Data Collection, Analysis, Writing – Review & Editing. Resources

Nirmala Vikram Shinde: Visualization, Supervision, Project Administration

References

- Louca P, Mompeo O, Leeming ER et al. Dietary influence on systolic and diastolic blood pressure in the TwinsUK cohort. Nutrients. 2020;12(7):2130. doi:10.3390/nu12072130

CrossRef - Leoncini G, Viazzi F, De Cosmo S, Russo G, Fioretto P, Pontremoli R. Blood pressure reduction and RAAS inhibition in diabetic kidney disease: therapeutic potentials and limitations. J Nephrol. 2020;33(5):949-963. doi:10.1007/s40620-020-00803-3

CrossRef - Verma T, Sinha M, Bansal N, Yadav SR, Shah K, Chauhan NS. Plants used as antihypertensive. Nat Prod Bioprospect. 2021;11:155-184. doi:10.1007/s13659-020-00281-x

CrossRef - Wang Y, Li Y, Ruan S, Lu F, Tian W, Ma H. Antihypertensive effect of rapeseed peptides and their potential in improving the effectiveness of captopril. J Sci Food Agric. 2021;101(7):3049-3055. doi:10.1002/jsfa.10900

CrossRef - Kim KJ, Hwang ES, Kim MJ, Park JH, Kim DO. Antihypertensive effects of polyphenolic extract from Korean red pine (Pinus densiflora et Zucc.) bark in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Antioxidants. 2020;9(4):333. doi:10.3390/antiox9040333

CrossRef - Sun D, Zhou T, Li X, et al. Genetic susceptibility, dietary protein intake, and changes of blood pressure: the POUNDS Lost trial. Hypertension. 2019;74(6):1460-1467. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.13510

CrossRef - Chung S, Chung MY, Choi HK, et al. Animal protein intake is positively associated with metabolic syndrome risk factors in middle-aged Korean men. Nutrients. 2020;12(11):3415. doi:10.3390/nu12113415

CrossRef - Mehrabani S, Asemi M, Najafian J, Sajjadi F, Maghroun M, Mohammadifard N. Association of animal and plant proteins intake with hypertension in Iranian adult population: Isfahan Healthy Heart Program. Adv Biomed Res. 2017;6:112. doi:10.4103/2277-9175.213877

CrossRef - Donfack MF, Atsamo AD, Guemmogne RJ, Kenfack OB, Dongmo AB, Dimo T. Antihypertensive effects of the Vitex cienkowskii (Verbenaceae) stem-bark extract on L-NAME-induced hypertensive rats. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2021;2021:Article ID 6632193. doi:10.1155/2021/6632193

CrossRef - Ghatage T, Goyal SG, Dhar A, Bhat A. Novel therapeutics for the treatment of hypertension and its associated complications: peptide- and nonpeptide-based strategies. Hypertens Res. 2021;44(7):740-755. doi:10.1038/s41440-021-00643-z

CrossRef - Kaur A, Kehinde BA, Sharma P, Sharma D, Kaur S. Recently isolated food-derived antihypertensive hydrolysates and peptides: a review. Food Chem. 2021;346:128719. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128719

CrossRef - Praveesh BV, Angayarkanni J, Palaniswamy M. Antihypertensive and anticancer effect of cow milk fermented by Lactobacillus plantarum and Lactobacillus casei. Int J Pharm Sci. 2011;3(5):452-456.

- Iwaniak A, Minkiewicz P, Darewicz M. Food-originating ACE inhibitors, including antihypertensive peptides, as preventive food components in blood pressure reduction. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2014;13(2):114-134. doi:10.1111/1541-4337.12036

CrossRef - Morales-Camacho JI, Espinosa-Hernández E, Rosas-Cárdenas FF, Semería-Maitret T, Luna-Suárez S. Insertions of antihypertensive peptides and their applications in pharmacy and functional foods. Appl MicrobiolBiotechnol. 2019;103:2493-2505. doi:10.1007/s00253-019-09720-0

CrossRef - Cicero AF, Rosticci M, Gerocarni B, et al. Lactotripeptides effect on office and 24-h ambulatory blood pressure, blood pressure stress response, pulse wave velocity and cardiac output in patients with high-normal blood pressure or first-degree hypertension: a randomized double-blind clinical trial. Hypertens Res. 2011;34(9):1035-1040. doi:10.1038/hr.2011.84

CrossRef - Matsui T, Tamaya K, Seki E, Osajima K, Matsumoto K, Kawasaki T. Val-Tyr as a natural antihypertensive dipeptide can be absorbed into the human circulatory blood system. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2002;29(3):204-208. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1681.2002.03607.x

CrossRef - World Health Organization. A Global Brief on Hypertension: Silent Killer, Global Public Health Crisis. 2013. Accessed June 2025.

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Tracking Heart Disease and Stroke in Canada. Ottawa, ON: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2009.

- Moser M, Franklin SS. Hypertension management: results of a new national survey for the Hypertension Education Foundation: Harris Interactive. J Clin Hypertens. 2007;9(5):316-323. doi:10.1111/j.1524-6175.2007.07134.x

CrossRef - de las Heras N, Ruiz-Ortega M, Rupérez M, et al. Role of connective tissue growth factor in vascular and renal damage associated with hypertension in rats. Interactions with angiotensin II. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2006;7(4):192-200. doi:10.3317/jraas.2006.034

CrossRef - US Department of Health & Human Services. HHS Secretary Sebelius Statement on National High Blood Pressure Education Month. Washington, DC: US Department of Health & Human Services; 2012.

- Gavras HA, Gavras IR. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Properties and side effects. Hypertension. 1988;11(3 Pt 2):II37-II44.

CrossRef - Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206-1252. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2

CrossRef - Mozaffarian D, Hao T, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Hu FB. Changes in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and men. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(25):2392-2404. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1014296

CrossRef - Craddick SR, Elmer PJ, Obarzanek E, Vollmer WM, Svetkey LP, Swain MC. The DASH diet and blood pressure. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2003;5(6):484-491.

CrossRef - Doaei S, Gholamalizadeh M. The association of genetic variations with sensitivity of blood pressure to dietary salt: a narrative literature review. ARYA Atheroscler. 2014;10(3):169-176.

- Rebholz CM, Friedman EE, Powers LJ, Arroyave WD, He J, Kelly TN. Dietary protein intake and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176(suppl_7):S27-S43. doi:10.1093/aje/kws189

CrossRef - Hartmann R, Meisel H. Food-derived peptides with biological activity: from research to food applications. Curr OpinBiotechnol. 2007;18(2):163-169. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2007.02.008

CrossRef - Martínez-Maqueda D, Miralles B, Recio I, Hernández-Ledesma B. Antihypertensive peptides from food proteins: a review. Food Funct. 2012;3(4):350-361. doi:10.1039/c2fo10203e

CrossRef - Zaman MA, Oparil S, Calhoun DA. Drugs targeting the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1(8):621-636. doi:10.1038/nrd899

CrossRef - De Ciuceis C, Porteri E, Rizzoni D, et al. Antioxidant treatment with melatonin and pycnogenol may improve the structure and function of mesenteric small arteries in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2009;54(6):e119.

- Cheung IW, Nakayama S, Hsu MN, Samaranayaka AG, Li-Chan EC. Angiotensin-I converting enzyme inhibitory activity of hydrolysates from oat (Avena sativa) proteins by in silico and in vitro analyses. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57(19):9234-9242. doi:10.1021/jf901730u

CrossRef - Marques C, Amorim MM, Pereira JO, Estevez Pintado M, Moura D, Calhau C, Pinheiro H. Bioactive peptides—Are there more antihypertensive mechanisms beyond ACE inhibition? Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(30):4706-4713. doi:10.2174/138161212802884898

CrossRef - Viera AJ, Neutze DM. Diagnosis of secondary hypertension: an age-based approach. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(12):1471-1478.

- Hall JE, Granger JP, do Carmo JM, et al. Hypertension: physiology and pathophysiology. Compr Physiol. 2012;2(4):2393-2442. doi:10.1002/cphy.c110035

CrossRef - Geleijnse JM, Engberink MF. Lactopeptides and human blood pressure. Curr OpinLipidol. 2010;21(1):58-63. doi:10.1097/MOL.0b013e328333fa3b

CrossRef - Mizushima S, Ohshige K, Watanabe J, et al. Randomized controlled trial of sour milk on blood pressure in borderline hypertensive men. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17(8):701-706. doi:10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.03.008

CrossRef - Engberink MF, Schouten EG, Kok FJ, Van Mierlo LA, Brouwer IA, Geleijnse JM. Lactotripeptides show no effect on human blood pressure: results from a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Hypertension. 2008;51(2):399-405. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.101721

CrossRef - Cicero AF, Gerocarni B, Laghi L, Borghi C. Blood pressure lowering effect of lactotripeptides assumed as functional foods: a meta-analysis of current available clinical trials. J Hum Hypertens. 2011;25(7):425-436. doi:10.1038/jhh.2010.94

CrossRef - Boelsma E, Kloek J. IPP-rich milk protein hydrolysate lowers blood pressure in subjects with stage 1 hypertension, a randomized controlled trial. Nutr J. 2010;9:47. doi:10.1186/1475-2891-9-47

CrossRef - Turpeinen AM, Ikonen M, Kivimäki AS, et al. A spread containing bioactive milk peptides Ile–Pro–Pro and Val–Pro–Pro, and plant sterols has antihypertensive and cholesterol-lowering effects. Food Funct. 2012;3(6):621-627. doi:10.1039/c2fo10267f

CrossRef - Turpeinen AM, Järvenpää S, Kautiainen H, Korpela R, Vapaatalo H. Antihypertensive effects of bioactive tripeptides—a random effects meta-analysis. Ann Med. 2013;45(1):51-56. doi:10.3109/07853890.2012.678462

CrossRef - Hirota T, Ohki K, Kawagishi R, et al. Casein hydrolysate containing the antihypertensive tripeptides Val-Pro-Pro and Ile-Pro-Pro improves vascular endothelial function independent of blood pressure–lowering effects: contribution of the inhibitory action of angiotensin-converting enzyme. Hypertens Res. 2007;30(6):489-496. doi:10.1291/hypres.30.489

CrossRef - Li H, Prairie N, Udenigwe CC, et al. Blood pressure lowering effect of a pea protein hydrolysate in hypertensive rats and humans. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59(18):9854-9860. doi:10.1021/jf202990k

CrossRef - Kawasaki T, Seki E, Osajima K, et al. Antihypertensive effect of valyl-tyrosine, a short chain peptide derived from sardine muscle hydrolysate, on mild hypertensive subjects. J Hum Hypertens. 2000;14(8):519-523. doi:10.1038/sj.jhh.1001038

CrossRef - Kawasaki T, Jun CJ, Fukushima Y, et al. Antihypertensive effect and safety evaluation of vegetable drink with peptides derived from sardine protein hydrolysates on mild hypertensive, high-normal and normal blood pressure subjects. Fukuoka Igaku Zasshi. 2002;93(10):208-218. doi:10.2733/fmj.93.208

- Matsui T, Tamaya K, Seki E, Osajima K, Matsumoto K, Kawasaki T. Absorption of Val–Tyr with in vitro angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitory activity into the circulating blood system of mild hypertensive subjects. Biol Pharm Bull. 2002;25(9):1228-1230. doi:10.1248/bpb.25.1228

CrossRef - Martínez-Maqueda D, Miralles B, Recio I, Hernández-Ledesma B. Antihypertensive peptides from food proteins: a review. Food Funct. 2012;3(4):350-361. doi:10.1039/c2fo10295k

CrossRef - Flack JM, Ference BA, Levy P. Should African Americans with hypertension be treated differently than non-African Americans? Curr Hypertens Rep. 2014;16(1):398. doi:10.1007/s11906-013-0398-9

CrossRef - Ferdinand KC, Nasser SA. A review of the efficacy and tolerability of combination amlodipine/valsartan in non-white patients with hypertension. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2013;13(5):301-313. doi:10.1007/s40256-013-0031-6

CrossRef - McCann KB, Shiell BJ, Michalski WP, et al. Isolation and characterisation of antibacterial peptides derived from the f (164–207) region of bovine αS2-casein. Int Dairy J. 2005;15(2):133-143. doi:10.1016/j.idairyj.2004.06.003

CrossRef - Hong F, Ming L, Yi S, Zhanxia L, Yongquan W, Chi L. The antihypertensive effect of peptides: a novel alternative to drugs? Peptides. 2008;29(6):1062-1071. doi:10.1016/j.peptides.2008.03.003

CrossRef - Vercruysse L, Van Camp J, Smagghe G. ACE inhibitory peptides derived from enzymatic hydrolysates of animal muscle protein: a review. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53(21):8106-8115. doi:10.1021/jf051771d

CrossRef - Nakashima Y, Arihara K, Sasaki A, Mio H, Ishikawa S, Itoh M. Antihypertensive activities of peptides derived from porcine skeletal muscle myosin in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Food Sci. 2002;67(1):434-437. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.2002.tb08781.x

CrossRef - Saiga A, Okumura T, Makihara T, et al. Angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitory peptides in a hydrolyzed chicken breast muscle extract. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51(6):1741-1745. doi:10.1021/jf020903b

CrossRef - Jang A, Lee M. Purification and identification of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitory peptides from beef hydrolysates. Meat Sci. 2005;69(4):653-661. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2004.10.012

CrossRef - Katayama K, Tomatsu M, Fuchu H, et al. Purification and characterization of an angiotensin I‐converting enzyme inhibitory peptide derived from porcine troponin C. Anim Sci J. 2003;74(1):53-58. doi:10.1111/j.1740-0929.2003.tb00426.x

- Cheng FY, Liu YT, Wan TC, Lin LC, Sakata R. The development of angiotensin I‐converting enzyme inhibitor derived from chicken bone protein. Anim Sci J. 2008;79(1):122-128. doi:10.1111/j.1740-0929.2007.00526.x

CrossRef - Arihara K, Nakashima Y, Mukai T, Ishikawa S, Itoh M. Peptide inhibitors for angiotensin I-converting enzyme from enzymatic hydrolysates of porcine skeletal muscle proteins. Meat Sci. 2001;57(3):319-324. doi:10.1016/S0309-1740(00)00136-5

CrossRef - Katayama K, Jamhari, Mori T, Kawahara S, et al. Angiotensin‐I converting enzyme inhibitory peptide derived from porcine skeletal muscle myosin and its antihypertensive activity in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Food Sci. 2007;72(9):S702-S706. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00526.x

CrossRef - Katayama K, Tomatsu M, Fuchu H, et al. Purification and characterization of an angiotensin I‐converting enzyme inhibitory peptide derived from porcine troponin C. Anim Sci J. 2003;74(1):53-58. doi:10.1111/j.1740-0929.2003.tb00426.x

CrossRef - Katayama K, Anggraeni HE, Mori T, et al. Porcine skeletal muscle troponin is a good source of peptides with angiotensin-I converting enzyme inhibitory activity and antihypertensive effects in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56(2):355-360. doi:10.1021/jf072607j

CrossRef - Theodore AE, Kristinsson HG. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition of fish protein hydrolysates prepared from alkaline‐aided channel catfish protein isolate. J Sci Food Agric. 2007;87(12):2353-2357. doi:10.1002/jsfa.2938

CrossRef - Kawasaki T, Seki E, Osajima K, Yoshida M, Asada K, Matsui T, Osajima Y. Antihypertensive effect of valyl-tyrosine, a short chain peptide derived from sardine muscle hydrolyzate, on mildly hypertensive subjects. J Hum Hypertens. 2000;14(8):519-523. doi:10.1038/sj.jhh.1001029

CrossRef - Samaranayaka AG, Kitts DD, Li-Chan EC. Antioxidative and angiotensin-I-converting enzyme inhibitory potential of a Pacific hake (Merluccius productus) fish protein hydrolysate subjected to simulated gastrointestinal digestion and Caco-2 cell permeation. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58(3):1535-1542. doi:10.1021/jf902875k

CrossRef - Hartmann R, Meisel H. Food-derived peptides with biological activity: from research to food applications. Curr OpinBiotechnol. 2007;18(2):163-169. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2007.02.013

CrossRef - Gatnau R, Polo J, Robert E. Plasma protein antimicrobial substitution at negligible risk. Feed ManufMediterr Region. 2001;54:141-150.

- Hsieh YH, Ofori J. Analysis of edible animal by-products. In: Handbook of Analysis of Edible Animal By-Products. CRC Press; 2011:13-35.

CrossRef - Silva VD, Silvestre MP. Functional properties of bovine blood plasma intended for use as a functional ingredient in human food. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2003;36(7):709-718. doi:10.1016/S0023-6438(03)00071-6

CrossRef - Hyun CK, Shin HK. Utilization of bovine blood plasma obtained from a slaughterhouse for economic production of probiotics. J Ferment Bioeng. 1998;86(1):34-37. doi:10.1016/S0922-338X(98)80005-0

CrossRef - Toldrá F, Aristoy MC, Mora L, Reig M. Innovations in value-addition of edible meat by-products. Meat Sci. 2012;92(3):290-296. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2012.05.009

CrossRef - Yu Y, Hu J, Miyaguchi Y, Bai X, Du Y, Lin B. Isolation and characterization of angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitory peptides derived from porcine haemoglobin. Peptides. 2006;27(11):2950-2956. doi:10.1016/j.peptides.2006.07.005

CrossRef - Adje EY, Balti R, Kouach M, Guillochon D, Nedjar-Arroume N. α67-106 of bovine haemoglobin: a new family of antimicrobial and angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitory peptides. Eur Food Res Technol. 2011;232(4):637-646. doi:10.1007/s00217-010-1407-4

CrossRef - McCarron DA, Morris CD, Henry HJ, Stanton JL. BP and nutrient intake in the United States. Science. 1984;224(4656):1392-1398. doi:10.1126/science.6722946

CrossRef - Garcia-Palmieri MR, Costas RA Jr, Cruz-Vidal ME, Sorlie PD, Tillotson JE, Havlik RJ. Milk consumption, calcium intake, and decreased hypertension in Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico Heart Health Program study. Hypertension. 1984;6(3):322-328. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.6.3.322

CrossRef - Reed DD, McGee D, Yano K, Hankin J. Diet, BP, and multicollinearity. Hypertension. 1985;7(3 Pt 1):405-410. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.7.3.405

CrossRef - Stamler J, Elliott P, Kesteloot H, et al. Inverse relation of dietary protein markers with BP: findings for 10,020 men and women in the INTERSALT study. Circulation. 1996;94(7):1629-1634. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.94.7.1629

CrossRef - Jäkälä P, Vapaatalo H. Antihypertensive peptides from milk proteins. Pharmaceuticals. 2010;3(1):251-272. doi:10.3390/ph3010251

CrossRef - Sharma S, Singh R, Rana S. Bioactive peptides: a review. Int J Bioautomation. 2011;15:223-250.

- Fitzgerald RJ, Murray BA. Bioactive peptides and lactic fermentations. Int J Dairy Technol. 2006;59(2):118-125. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0307.2006.00252.x

CrossRef - Ruiz JA, Ramos M, Recio I. Angiotensin-converting enzyme-inhibitory activity of peptides isolated from Manchego cheese. Stability under simulated gastrointestinal digestion. Int Dairy J. 2004;14(12):1075-1080. doi:10.1016/j.idairyj.2004.04.009

CrossRef - Jarmołowska B, Kostyra E, Krawczuk S, Kostyra H. β-Casomorphin-7 isolated from Brie cheese. J Sci Food Agric. 1999;79(13):1788-1792. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0010(199910)79:13<1788::AID-JSFA488>3.0.CO;2-R

CrossRef - Ferranti P, Barone F, Chianese L, et al. Phosphopeptides from Grana Padano cheese: nature, origin, and changes during ripening. J Dairy Res. 1997;64(4):601-615. doi:10.1017/S0022029997003372

CrossRef - Muehlenkamp MR, Warthesen JJ. β-Casomorphins: Analysis in cheese and susceptibility to proteolytic enzymes from Lactococcus lactis ssp. cremoris. J Dairy Sci. 1996;79(1):20-26. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(96)76304-4

CrossRef - Hernández-Ledesma B, Amigo L, Ramos M, Recio I. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitory activity in commercial fermented products. Formation of peptides under simulated gastrointestinal digestion. J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52(6):1504-1510. doi:10.1021/jf035152j

CrossRef - Hernández-Ledesma B, Amigo L, Ramos M, Recio I. Release of angiotensin-converting enzyme-inhibitory peptides by simulated gastrointestinal digestion of infant formulas. Int Dairy J. 2004;14(10):889-898. doi:10.1016/j.idairyj.2004.04.015

CrossRef - Korhonen H. Milk-derived bioactive peptides: from science to applications. J Funct Foods. 2009;1(2):177-187. doi:10.1016/j.jff.2009.01.002

CrossRef - Kumar R, Chaudhary K, Sharma M, Nagpal G, Chauhan JS, Singh S, Gautam A, Raghava GP. AHTPDB: a comprehensive platform for analysis and presentation of antihypertensive peptides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(D1):D956-D962. doi:10.1093/nar/gku1144

CrossRef - Udenigwe CC, Aluko RE. Food protein‐derived bioactive peptides: production, processing, and potential health benefits. J Food Sci. 2012;77(1):R11-R24. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02591.x

CrossRef - Bhat ZF, Kumar S, Bhat HF. Antihypertensive peptides of animal origin: A review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017;57(3):566-578. doi:10.1080/10408398.2014.961565

CrossRef - Murtaza MA, Irfan S, Hafiz I, Ranjha MM, Rahaman A, Murtaza MS, Ibrahim SA, Siddiqui SA. Conventional and novel technologies in the production of dairy bioactive peptides. Front Nutr. 2022;9:780151. doi:10.3389/fnut.2022.780151

CrossRef - van den Broek I, Sparidans RW, Schellens JH, Beijnen JH. Quantitative bioanalysis of peptides by liquid chromatography coupled to (tandem) mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2008;872(1-2):1–22. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2008.07.041

CrossRef - Zhang H, Xin B, Caporuscio C, Olah TV. Bioanalytical strategies for developing highly sensitive liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry based methods for the peptide GLP-1 agonists in support of discovery PK/PD studies. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2011;25(22):3427–35. doi:10.1002/rcm.5250

CrossRef - Ewles M, Goodwin L. Bioanalytical approaches to analyzing peptides and proteins by LC-MS/MS. Bioanalysis. 2011;3(12):1379–97. doi:10.4155/bio.11.81

CrossRef - Javid S, Ramya K, Ahmed MG, Zahiya N, Thansheefa N, Anas AK, et al. Bioanalysis of antihypertensive drugs by LC-MS: a fleeting look at the regulatory guidelines and artificial intelligence. Bioanalysis. 2025:1–17. doi:10.4155/bio-2025-0055

CrossRef - Yin N, Brimble MA, Harris PWR, Wen J. Enhancing the oral bioavailability of peptide drugs by using chemical modification and other approaches. Med Chem (Los Angeles). 2014;4:763–9. doi:10.4172/2161-0444.1000227

CrossRef - Maher S, Ryan B, Duffy AJ, Brayden DJ. Formulation strategies to improve oral peptide delivery. Pharm Pat Anal. 2014;3(3):313–36. doi:10.4155/ppa.14.18

CrossRef - Hamman JH, Enslin GM, Kotzé AF. Oral delivery of peptide drugs: barriers and developments. BioDrugs. 2005;19(3):165–77. doi:10.2165/00063030-200519030-00003

CrossRef - Maher S, Brayden DJ. Overcoming poor permeability: translating permeation enhancers for oral peptide delivery. Drug Discov Today Technol. 2012;9(2):e71–e174. doi:10.1016/j.ddtec.2011.11.003

CrossRef - Tang LS, Persky AM, Hochhaus G, Meibohm B. Pharmacokinetic aspects of biotechnology products. J Pharm Sci. 2004;93(9):2184–204. doi:10.1002/jps.20139

CrossRef - Taki Y, Sakane T, Nadai T, Sezaki H, Amidon GL, Langguth P, et al. First-pass metabolism of peptide drugs in rat perfused liver. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1998;50(9):1013–8. doi:10.1111/j.2042-7158.1998.tb06916.x

CrossRef - Hall MP. Special Section on DMPK of Therapeutic Proteins—Minireview Biotransformation and in vivo stability of protein biotherapeutics: impact on candidate selection and pharmacokinetic profiling. Bioanalysis. 2014;6(15):2009–26. doi:10.4155/bio.14.126

CrossRef - Fletcher EP, Sahre MD, Hon YY, Balakrishnan A, Zhou L, Sun Q, et al. Impact of organ impairment on the pharmacokinetics of therapeutic peptides and proteins. AAPS J. 2023;25(3):51. doi:10.1208/s12248-023-00845-w

CrossRef - Nielsen CU, Brodin B, Jørgensen FS, Frokjaer S, Steffansen B. Human peptide transporters: therapeutic applications. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2002;12(9):1329–50. doi:10.1517/13543776.12.9.1329

CrossRef - Terada T, Inui K. Peptide transporters: structure, function, regulation and application for drug delivery. Curr Drug Metab. 2004;5(1):85–94. doi:10.2174/1389200043489208

CrossRef - Freeman HJ. Clinical relevance of intestinal peptide uptake. World J GastrointestPharmacol Ther. 2015;6(2):22–7. doi:10.4292/wjgpt.v6.i2.22

CrossRef

Abbreviations List

BP:Blood Pressure

ACE: Angiotensin Converting Enzyme

AHPs: Active Hypotensive Peptides

RAS: Renin-Angiotensin System

SBP: Systolic Blood Pressure

DBP: Diastolic Blood Pressure

IPP: Ile-Pro-Pro

VPP: Val-Pro-Pro

VY: Val-Tyr

CHD: Coronary Heart Disease

LDL: Low-Density Lipoprotein

DASH: Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension

SHR: Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats

Ang-II receptors: Angiotensin-II receptors

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.