Manuscript accepted on : 03 Sep 2025

Published online on: 17-09-2025

Plagiarism Check: Yes

Reviewed by: Dr. Ichrak Jaouadi

Second Review by: Dr. Rajendra Jangde

Final Approval by: Dr. Eugene A. Silow

Deshoju Sneha , Riya Jain, Nagalakshmi Devaraju

, Riya Jain, Nagalakshmi Devaraju , Nuzhat Sheikh, Zagade Akshay Sunil, Suman Jangir

, Nuzhat Sheikh, Zagade Akshay Sunil, Suman Jangir and Varalakshmi Kilingar Nadumane*

and Varalakshmi Kilingar Nadumane*

Centre for Research in Pure and Applied Sciences, Department of Biotechnology, School of Sciences, Jain Deemed-to-be-University, Bangalore, Karnataka, India.

Corresponding Author E-mail:kn.varalakshmi@jainuniversity.ac.in

ABSTRACT: Cancer is a major global health concern due to the high mortality rate associated with it. Only cancer cells exhibit methionine dependency, and cannot proliferate in a methionine-depleted environment. Hence, L-methionase has drawn considerable attention as a potential treatment for cancer. Based on this, the present study was aimed on the isolation and purification of L-Methioninase from microbes, and evaluation of its cytotoxic effects on liver cancer (HepG2) and cervical cancer (HeLa) cell lines. Different samples were collected for the isolation of microorganisms capable of producing L-methioninase. The enzymes from these were further purified by ammonium sulphate and acetone precipitations. The purified enzymes were treated on to HepG2 and HeLa cell lines and checked for cytotoxicity by MTT, LDH and trypan blue assays. The molecular docking of L-methioninase to methionine and homocysteine were assessed through AutoDock tools 1.5.7. Among the 21 isolates, 4 microbial isolates were shortlisted based on their L-methioninase activity. These 4 isolates were named as B4 and B6 (Bacteria), F6 (fungi), A2 (Actinomycete). The results were analyzed using Pymol. The purified L-methioninase from two isolates were having high methioninase activity and cytotoxicity and identified as Pseudomonas plecoglossicida JUB4 and Streptomyces cavourensis JUA2. L-methioninase from these isolates had promising anticancer properties, and hence show promise towards further purification, characterization, and anticancer applications.

KEYWORDS: Anticancer; Homocystein; L-Methioninase; Molecular Docking; Pseudomonas plecoglossicida; Streptomyces cavourensis

| Copy the following to cite this article: Sneha D, Jain R, Devaraju N, Sheikh N, Sunil Z. A, Jangir S, Nadumane V. K. Comparative L-Methioninase Activity, Anticancer Activity and Molecular Docking Studies of L-Methioninase from Microbial Isolates. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(3). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Sneha D, Jain R, Devaraju N, Sheikh N, Sunil Z. A, Jangir S, Nadumane V. K. Comparative L-Methioninase Activity, Anticancer Activity and Molecular Docking Studies of L-Methioninase from Microbial Isolates. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(3). Available from: https://bit.ly/46pHMiu |

Introduction

Cancer is a condition marked by the uncontrolled growth of abnormal cells in the body. Worldwide, cancer is a leading cause of mortality and morbidity. Cells may become cancerous and resist normal growth controls as a result of specific gene alterations. A variety of therapies and treatments have been developed to inhibit the growth of tumors or cancer cells in a small percentage of patients. These include radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and surgery. Furthermore, several cancer gene therapy techniques have been established.1 However, gene therapy experiments have so far shown limited clinical effects and, in some cases, fatal toxicity.2 Therefore, there is a need for alternative methods of cancer treatment.

Enzyme therapy is one such novel approach. Various enzymes, including L-asparaginase, arginine deiminase, and L-glutaminase, are recognized as key microbial enzymes in antitumor therapy. Among them, L-asparaginase is extensively used in the treatment of lymphosarcoma, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Hodgkin’s disease, and several other types of tumors.3 A major concern with L-asparaginase administration is its potential to trigger anaphylactic reactions, whereas such issues have not been reported with L-methioninase.4 L-Methionine-γ-lyase (MGL), also known as methionase, is a pyridoxal phosphate (PLP)-dependent enzyme. MGL catalyzes the conversion of L-methionine into methanethiol, ammonia, and α-ketobutyrate, thereby depleting methionine in the cellular environment.5 Methionine, an essential amino acid, is required in elevated amounts by many human tumor cells because it supports high DNA expression and protein synthesis. Methionine synthase is present in healthy cells, and it converts homocysteine into methionine using methyl tetrahydrofolate and betaine as methyl donors. However, only cancer cells exhibit the metabolic abnormality known as methionine dependency and cannot proliferate in a methionine-depleted environment. The methionine dependence of tumors, in contrast to normal cells, has been previously documented.4,6 Thus, L-methioninase has received considerable attention as a therapeutic enzyme against various methionine-dependent tumors. Microorganisms are a convenient and important source for the commercial production of L-methioninase. Consequently, numerous efforts have focused on producing L-methioninase from microbial sources such as fungi and bacteria. Although fungi present an appealing option for enzyme production, the possible risk of anaphylactic reactions from fungal sources remains a significant drawback.4 Bacteria, protozoans, archaea, and plants produce intracellular L-methionine-γ-lyase. Some fungi, a few bacteria, and actinomycetes produce it extracellularly.7

Due to the significance of L-methioninase in cancer therapy and based on its relative safety over other enzymes, the current study was aimed to identify an efficient methioninase-producing microorganism that produces L-methioninase extracellularly, purify it, and evaluate its anticancer potential in vitro against different cancer cell lines.

Material and Methods

Isolation of Microorganisms

The serial dilution method was used to isolate microorganisms from soil and other samples, following standard protocols.8 Serial dilution is a method used to stepwise dilute substance into solution with constant dilution factor in each step with equal proportion. 100 ml of saline was prepared with 0.85 % NaCl. 1gm of soil sample collected from different locations was weighed and added to 9ml of saline and volume was made up to 10ml. Different concentrations were prepared such as 10-1, 10-2, 10-3, 10-4, 10-5 and 10-6 each of which was diluted serially. Further, these serially diluted samples were used for isolating microorganisms by spread plate method.8

Media for isolation of microorganisms for Rapid screening

M9 medium is a minimal growth medium used for isolating bacterial cultures. M9 medium was primarily used for isolating L-methioninase-producing microorganisms, as it contains L-methionine.9 Since methionine is the sole energy source in this medium, only organisms capable of degrading it can grow on it. Colonies that appear pink in color indicate the production of L-methioninase. The components of M9 medium are listed in Table 1.

Table 1: Components of M9 medium

| Components (g/L) | 250 mL | 400 mL | 1000 mL |

| Na2HPO4 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 6 |

| KH2PO4 | 0.75 | 1.2 | 3 |

| NaCl | 0.125 | 0.2 | 0.5 |

| L-Methionine | 1.25 | 2 | 5 |

| MgSO4 | 0.06 | 0.096 | 0.24 |

| CaCl2 | 0.0027 | 0.0044 | 0.011 |

| Glucose | 0.5 | 0.8 | 2 |

| Phenol red | 0.01% | 0.01% | 0.01% |

| Agar (2%) | 5 | 8 | 20 |

L-Methioninase enzyme activity assay

Materials

Methionine is an essential amino acid that contains an aliphatic R group and is nonpolar in nature. Pyridoxal phosphate (PLP) acts as a coenzyme in all transamination reactions of amino acids. 5,5′-Dithiobis-(2-Nitrobenzoic Acid) (DTNB), also called Ellman’s reagent, reacts with sulfhydryl groups to yield a-colored product, providing a reliable method to measure reduced cysteine and other free sulfhydryl groups in solution.

L-methioninase activity was assayed using L-methionine as the substrate. Methanethiol (MTL) produced from the substrate reacts with 5,5′-Dithiobis-(2-Nitrobenzoic Acid) (DTNB; Sigma–Aldrich) to form 5-thionitrobenzoic acid, which can be detected spectrophotometrically at 412 nm. The reaction mixture consists of 20 mM L-methionine in 0.05 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 0.01 mM pyridoxal phosphate (PLP; Sigma–Aldrich), 0.25 mM DTNB, and microbial culture filtrate, in a final volume of 1 ml. After 1 h of incubation at 30°C, the increase in absorbance of the developed color was measured at 412 nm.10 Controls with heat-denatured filtrate (at 95°C for 30 minutes) were processed separately. The amount of methanethiol released was calculated from a standard curve prepared with sodium methanethiolate.

One unit (U) of L-methioninase activity is defined as the amount of enzyme that liberates 1 μmole of methanethiol perminute under the specified assay conditions. The specific activity was determined by dividing the enzyme activity by the protein content (mg) of the sample and is expressed as U/mg of protein.

Estimation of Protein content

The protein content of the enzyme sample was determined according to the standard methodology.11

Purification of the enzyme by Acetone Precipitation

The culture supernatant (containing the enzyme) was separated by centrifugation and then precipitated with chilled acetone at a 1:2 (supernatant to acetone) ratio.12 The mixture was kept at -20°C overnight. Subsequently, the precipitated enzyme was collected by cold centrifugation, and the pellet was stored for further use.

Purification by Ammonium sulphate precipitation

The L-methioninase enzyme (protein) was purified using the ammonium sulfate precipitation method by altering the solubility of proteins.13 Ammonium sulfate is commonly used due to its high solubility, which allows for the preparation of solutions with a high ionic strength. Different concentrations of ammonium sulfate (0–30%, 30–60%, and 60–80% saturation) were used to precipitate L-methioninase. The proteins were then collected by centrifugation, and the precipitate was dialyzed to remove excess salts. The dialyzed samples were subsequently concentrated by lyophilization and stored for further use.

Cytotoxicity assessment by MTT assay

The yellow tetrazolium dye MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) is reduced by metabolically active cells, in part by the action of dehydrogenase enzymes, to generate reducing equivalents such as NADH and NADPH. The resulting intracellular purple formazan can be solubilized and quantitated by spectrophotometric means.14 The MTT assay was performed in triplicate using different concentrations of various samples, including microbial culture supernatant, protein precipitate, and lyophilized sample. To evaluate the cytotoxic effects of the enzyme precipitate, a 1 mg/ml solution of each sample was prepared in 0.1 M PBS and added to the wells in different volumes (15 μl, 30 μl, 50 μl from ammonium sulfate precipitation — corresponding to 15, 30, and 50 μg/ml, respectively; and 1 μl, 5 μl, 10 μl from acetone precipitation). For the lyophilized sample, volumes of 10 μl, 20 μl, 30 μl, 40 μl, and 50 μl were used. HeLa (cervical cancer) and HepG2 (liver cancer) cell lines were trypsinized, collected, and seeded at a density of 2 × 104 cells/ml into the wells of a 96-well microtiter plate. The cells were allowed to adhere for 24 hours prior to sample treatment. Enzyme treatment was carried out for 48 hours, after which the assay was performed according to the described methodology.

Observation of HepG2 cell morphology

HepG2 cells treated with partially purified L-methioninase (obtained by acetone precipitation) were observed under an inverted microscope for any morphological changes and were photographed.

Trypan Blue Assay

Trypan blue is one of several stains recommended for use in dye exclusion assays for viable cell counting. This method is based on the principle that viable cells exclude the dye, while non-viable cells take it up.15 Staining also assists in visualizing cell morphology.

After 48 hours of enzyme treatment, the cancer cells were stained with 0.4% trypan blue dye (in PBS) and counted under a binocular microscope using a haemocytometer.

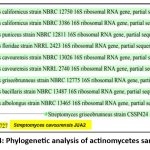

LDH activity assay

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) is a cytosolic enzyme present in a wide range of cell types. LDH is released into the culture medium when the plasma membrane is damaged. In a coupled enzymatic reaction, extracellular LDH catalyzes the conversion of lactate to pyruvate while reducing NAD to NADH. Subsequently, diaphorase uses this NADH to reduce a tetrazolium salt into a red formazan product, which can be detected spectrophotometrically at 490 nm.16 The 48-hour enzyme-treated cancer cells were subjected to the LDH assay following the standard procedure provided in the LDH assay kit manual. The cytotoxicity caused by the enzyme sample was calculated using the following formula:

Molecular docking

The docking studies of L-Methionine-L-Methioninase and L-Homocysteine-L-Methioninase were carried out using AutoDock Vina 4.2.17 The 3D structure of the enzyme L-Methioninase was downloaded from the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 1UKJ). The 3D conformers of the substrates L-Methionine (PubChem CID: 6137) and L-Homocysteine (PubChem CID: 91552) were downloaded from PubChem. The protein (enzyme) and ligand (substrates) were prepared using AutoDock Tools 1.5.7 and saved in PDBQT format.

A grid box was generated to define the x-, y-, and z-coordinates of the macromolecule, and a config file was created using these grid dimensions. The AutoDock run was then performed using Vina through Command Prompt, which resulted in the generation of a log file. Finally, the results were analyzed and visualized using PyMol.

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were carried out in triplicates. The results were expressed as mean ± standard error (SE) Values. Statistical significance was calculated using one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using Graph Pad Prism software. The values < 0.05 were taken as significant.

Results

Microorganisms isolated

Different samples, such as rhizosphere soil, plant leaves, and seaweed, were collected from various locations in Bangalore, Mysore, Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu to isolate microbes capable of producing L-methioninase. Serial dilutions of soil samples were plated on M9 medium and incubated to allow microbial growth. M9 medium, a differential and selective medium, supports the growth of organisms with the ability to produce L-methioninase.

Bacterial growth was observed after 48 hours of incubation at 37°C, with pink-colored colonies indicating L-methioninase producers. Fungi and actinomycetes were observed after 4 days of incubation at 25°C (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1: The photos showing the growth of (a) fungi (b) actinomycetes (c) bacteria. Arrows indicate pink colonies which are positive for L-methioninase production. |

The soil samples from Bangalore, Mysore, Hubli, and Solapur showed growth of different microbes (Table 2).

Table 2: Samples showing microbial growth.

| LOCATION | SAMPLE | GROWTH OBSERVED | ||

| bacteria | Fungi | actinomycetes | ||

| BENGALURU | SOIL | + | + | – |

| MYSORE | SOIL | + | – | + |

| HUBLI | SOIL | + | + | + |

| SOLAPUR | SOIL | + | – | – |

The above results indicate that these organisms were able to grow on methionine media, demonstrating their ability to produce L-methioninase. A total of 21 isolates were obtained from this screening process. The isolates were classified and labeled as follows:

Bacteria: B1, B2, B3, B4, B5, B6, B7, B8

Actinomycetes: A1, A2, A3, A4, A5, A6

Fungi: F1, F2, F3, F4, F5, F6, F7

L-methioninase activity of the isolates

The microbial isolates were further shortlisted based on their L-methioninase activity, which was measured using sodium methanethiolate as a standard. The highest L-methioninase activity was shown by the fungal isolate F6, with 0.168 μmoles/minute/ml and a specific activity of 1.82 U/mg of protein (Table 3). The second highest activity was observed in the bacterial isolate B4, with 0.097 μmoles/minute/ml, followed by the actinomycete A2 and the bacterial isolate B6, both with 0.094 μmoles/minute/ml. The highest specific activity was demonstrated by B4 (4.21 U/mg protein), followed by A2 (2.35 U/mg protein).

These four isolates were selected for further studies based on their enzyme activity and specific activity. Isolates from bacteria, actinomycetes, and fungi were chosen for subsequent investigations.

Table 3: L-methioninase activity (µMoles/min/ml) of the chosen samples. Specific activity is expressed as mean of duplicate experiments.

| S. No. | SAMPLE | OD at 412nm | ENZYME ACTIVITY | OD 660nm | PROTEIN CONTENT

(mg/mL) |

SPECIFIC ACTIVITY

(U/mg protein) |

| 1. | B1 | 0.240 | 0.071 | 0.020 | 0.018 | 3.94 |

| 2. | B2 | 0.113 | 0.034 | 0.111 | 0.044 | 0.0772 |

| 3. | B3 | 0.067 | 0.017 | 0.354 | 0.14 | 0.121 |

| 4. | B4 | 0.333 | 0.097 | 0.579 | 0.023 | 4.21 |

| 5. | B5 | 0.177 | 0.051 | 0.045 | 0.016 | 3.18 |

| 6. | B6 | 0.326 | 0.094 | 0.126 | 0.048 | 1.95 |

| 7. | B7 | 0.106 | 0.028 | 0.111 | 0.044 | 0.6363 |

| 8. | B8 | 0.090 | 0.025 | 0.105 | 0.04 | 0.625 |

| 9. | A1 | 0-223 | 0.065 | 0.090 | 0.046 | 1.41 |

| 10. | A2 | 0.328 | 0.094 | 0.103 | 0.040 | 2.35 |

| 11. | A3 | 0.232 | 0.068 | 0.185 | 0.072 | 0.944 |

| 12. | A4 | 0.070 | 0.022 | 0.020 | 0.08 | 0.275 |

| 13. | A5 | 0.065 | 0.017 | 0.355 | 0.140 | 0.121 |

| 14. | A6 | 0.023 | 0.005 | 0.050 | 0.020 | 0.25 |

| 15. | F1 | 0.180 | 0.054 | 0.063 | 0.024 | 2.25 |

| 16. | F2 | 0.019 | 0.002 | 0.033 | 0.012 | 0.166 |

| 17. | F3 | 0.215 | 0.062 | 0.025 | 0.07 | 0.88 |

| 18. | F4 | 0.158 | 0.045 | 0.111 | 0.044 | 1.022 |

| 19. | F5 | 0.216 | 0.062 | 0.134 | 0.052 | 1.192 |

| 20. | F6 | 0.576 | 0.168 | 0.232 | 0.092 | 1.82 |

| 21. | F7 | 0.278 | 0.079 | 0.112 | 0.044 | 1.79 |

Selection of isolates

Among the 21 isolates obtained from different locations, 4 were selected for further studies on the purification of L-methioninase, as these isolates demonstrated the highest enzyme activity. The bacterial isolate B4 had shown the highest specific activity of L-methioninase with 4.21 U/mg protein, second best activity by A2 with 2.35 U/mg protein, followed by B6 and F6 with 1.95 and 1.82 U/mg protein, respectively. Hence, these 4 isolates were selected due to their higher enzyme activities than all other isolates. Among them two were bacteria (B4 and B6), one was an actinomycete (A2), and the other one was a fungal isolate (F6) (Figure 2).

|

Figure 2: Pure culture of the selected four microbial isolates. (a) A2; (b) B4; (c) F6; (d) B6 |

Isolation and purification of L-methioninase enzyme

Ammonium sulphate precipitation

Ammonium sulfate precipitation, also known as “salting out,” utilizes high concentrations of salt to precipitate proteins. The procedure was carried out at different ammonium sulfate saturations — 0–30%, 30–60% and 60–80%. Each protein has a specific range of ammonium sulfate at which it precipitates. The pellets were collected and dissolved in PBS. Ammonium sulfate precipitation was performed on the shortlisted samples, and L-methioninase activity was determined.

L-methioninase activity of ammonium sulphate precipitated proteins

The specific activity of both the pellet and supernatant fractions was measured and tabulated (Table 4 & 5). The enzyme activity of A2 and B4 was found to be high (4.25 U/mg for A2 and 29.75 U/mg for B4) when compared to F6 and B6. These two isolates were selected for further purification and anticancer analysis and were subsequently identified by 16S rRNA sequencing (at Biokart India Pvt Ltd, Bengaluru).

Table 4: L-methioninase Activity of the precipitated proteins. Specific activity is expressed as mean ± SE

| Sample (0-30%) | Enzyme activity (µmoles/min/mL) | Protein content (mg) | Specific activity (U/mg) |

| A2 | 0.034 | 0.008 | 4.25 ± 0.1 |

| F6 | 0.014 | 0.022 | 0.636 ± 0.03 |

| B4 | 0.136 | 0.046 | 2.95 ± 0.02 |

| B6 | 0.148 | 0.128 | 1.15 ± 0.07 |

| Sample (30-60%) | Enzyme activity (µmoles/min/mL) | Protein content (mg) | Specific activity (U/mg) ± |

| A2 | 0.031 | 0.074 | 0.418 ± 0.05 |

| F6 | 0.017 | 0.020 | 0.85 ± 0.09 |

| B4 | 0.119 | 0.004 | 29.75 ± 0.2 |

| B6 | 0.039 | 0.192 | 0.20 ± 0.01 |

Table 5: L-methioninase Activity of the supernatant. Specific activity is expressed as mean ± SE

| Sample (0-30%) | Enzyme activity (µmoles/min/mL) | Protein content (mg) | Specific activity (U/mg) |

| A2 | 0.031 | 0.230 | 0.134 ± 0.03 |

| F6 | 0.014 | 0.022 | 0.636 ± 0.05 |

| B4 | 0.039 | 0.222 | 0.175 ± 0.02 |

| B6 | 0.028 | 0.344 | 0.081 ± 0.004 |

| Sample (30-60%) | Enzyme activity (µmoles/min/mL) | Protein content (mg) | Specific activity (U/mg) |

| A2 | 0.019 | 0.266 | 0.071 ± 0.002 |

| F6 | 0.031 | 0.104 | 0.298 ± 0.04 |

| B4 | 0.022 | 0.218 | 0.10 ± 0.002 |

| B6 | 0.022 | 0.344 | 0.063 ± 0.001 |

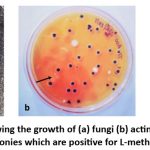

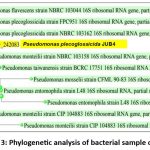

Identification of the potential isolates

The bacterial isolate B4 was observed as closely related to Pseudomonas plecoglossicida strain NBRC 10316 (99% similarity) based on 16S ribosomal RNA gene partial sequence (Sequence ID: NR_114226.1). Therefore, it was designated as Pseudomonas plecoglossicida JUB4 in the present study (Figure 3).

The actinomycetes isolate A2 was closely related to Streptomyces cavourensis strain NRRL 2740 (99% similarity) based on 16S ribosomal RNA gene partial sequence (Sequence ID: NR_04851.1). Therefore, it was designated as Streptomyces cavourensis JUA2 in the present study (Figure 4).

|

Figure 3: Phylogenetic analysis of bacterial sample of B4 |

|

Figure 4: Phylogenetic analysis of actinomycetes sample of A2 |

Purification of L-methioninase by Acetone precipitation

Among the isolates, A2 and B6 yielded a greater amount of protein precipitate when compared. L-methioninase activity was assayed in the proteins precipitated by acetone and the results were tabulated (Table 6). The results show that the activity remained high for samples A2 and B4 even after acetone precipitation.

Table 6: L-methioninase activity of acetone precipitated samples. Specific activity is expressed as mean ± SE

| Sample | Enzyme activity (µMoles/min/mL) | Protein content (mg) | Specific activity (U/mg) |

| A2 | 0.014 | 0.100 | 0.14 ± 0.001 |

| F6 | 0.005 | 0.166 | 0.010 ± 0.001 |

| B4 | 0.071 | 0.322 | 0.22 ± 0.003 |

| B6 | 0.017 | 0.400 | 0.04 ± 0.004 |

Cytotoxicity of the crude and partially purified enzyme by MTT assay

When HeLa cells, subcultured into 96-well plates for 24 hours, were treated with the culture supernatants (containing L-methioninase) of the selected isolates for 48 hours, the highest inhibition of cell proliferation was observed for the A2 sample. The percentage viability was 89.58% for A2, followed by 92.75% for B4, and 95.01% for F6 (Figure 5). The other isolates did not show significant cytotoxic effects.

|

Figure 5: Effect of different concentrations of microbial culture supernatants on HeLa cell viability (%). |

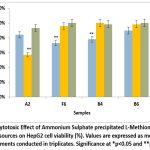

Ammonium sulphate precipitated L-methioninase tested on HepG2 cells

When HepG2 cells were treated with ammonium sulphate-precipitated samples dissolved in phosphate buffer, the highest cytotoxic effect was observed for the A2 (Streptomyces cavourensis) sample, with cell viability reduced to 56.9% at 30 µl treatment (Figure 6). This was followed by the F6 sample, which resulted in 72% viability at 15 µl, and the B4 (P. plecoglossicida) sample, with 78.18% viability at 15 µl.

|

Figure 6: Cytotoxic Effect of Ammonium Sulphate precipitated L-Methioninase from microbial sources on HepG2 cell viability (%). |

Acetone precipitated L-methioninase tested on HepG2 cells

When acetone-precipitated L-methioninase samples were treated on HepG2 cells, the Pseudomonas plecoglossicida (B4) sample at 100 µg/ml demonstrated the highest cytotoxic effect, reducing the viability of HepG2 cells to 53.3% after 48 hours of treatment. This was followed by the Streptomyces cavourensis (A2) sample at 100 µg/ml, which reduced the cell viability of HepG2 to 63%, and at 10 µg/ml, the S. cavourensis (A2) sample resulted in reducing the viability to 70% in treated HepG2 cells (Table 7).

Table 7: Effect of acetone purified L-methioninase samples on HepG2 cell viability (%).

| Samples | 10µg/ml | 50µg/ml | 100µg/ml |

| A2 | 69.93% | 73.33% | 63.03% |

| F6 | 78.18% | 71.51% | 84.24% |

| B4 | 86.06% | 75.75% | 53.33% |

| B6 | 81.21% | 81.21% | 75.75% |

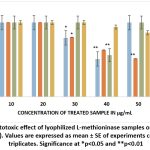

Effect of Lyophilized L-methioninase on the viability of HepG2 cells

When ammonium sulphate-precipitated samples of A2 and B4 were lyophilized and treated to HepG2 cells, the highest cytotoxic effect was observed with S. cavourensis (A2) at 40 µg/ml, reducing cell viability to 51.83%. P. plecoglossicida (B4) at the same concentration (40 µg/ml) resulted in 56.2% viability of treated HepG2 cells. Furthermore, when the acetone-precipitated S. cavourensis (A2) sample was applied at 50 µg/ml, the viability of HepG2 cells fell to 51.52%. At 40 µg/ml of the acetone-precipitated A2, viability was 63.09%. However, the acetone-precipitated P. plecoglossicida (B4) sample did not show significant cytotoxic effects; the viability remained 94% at 40 µg/ml and 86.24% at 50 µg/ml. In the case of P. plecoglossicida L-methioninase, only the ammonium sulphate-precipitated enzyme demonstrated cytotoxic effects against HepG2 cells (Figure 7).

|

Figure 7: Cytotoxic effect of lyophilized L-methioninase samples on HepG2 cell viability (%). |

HeLa and HepG2 cell morphology under the microscope

When HepG2 (liver cancer) and HeLa (cervical cancer) cells were treated with the partially purified enzyme for 48 hours and observed under an inverted microscope, the treated cells exhibited a reduction in their number and had detached from the bottom of the culture flask. Furthermore, visible apoptotic bodies were observed in the treated cells, in contrast to the control flask, where the cells were fully confluent and firmly attached to the surface (Figure 8).

|

Figure 8: Photographs of HeLa and HepG2 cells under the inverted microscope. (a) control HeLa cells (b) HeLa cells treated with L-methioninase from S. cavourensis (c) Control HepG2 cells (d) L-methioninase treated HepG2. |

Cell concentration by trypan blue assay

The samples treated with different concentrations of lyophilized A2 and B4, and the acetone-precipitated samples of the same, demonstrated an increase in non-viable cells taking up the trypan blue stain (Table 8). According to our results, the acetone-precipitated L-methioninase from A2 resulted in a significant reduction in HepG2 cell viability to 79% after 48 hours of treatment, as compared to the control, which remained at 88%. The B4 lyophilized sample maintained a viability of 90%. The highest number of non-viable cells were observed in the A2 acetone-precipitated sample (369 cells/mL) treated to HepG2, which was greater than the ammonium sulfate-purified sample (113 cells/mL).

Table 8: Cell count and Percentage viability of HepG2 cells treated with L-methioninase samples.

| Sample | Cell Count (1×103 cells/mL) | Viability (%) | |

| Viable cells | Non-viable

Cells |

||

| A2 (LYO) | 1.574 | 0.113 | 93.3 |

| A2 (ACETONE) | 1.389 | 0.369 | 79.01 |

| B4 (LYO) | 1.677 | 0.167 | 90.94 |

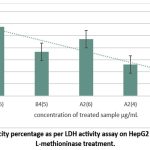

LDH cytotoxicity

Among the four different samples tested on HepG2 cells, the acetone-precipitated A2 sample exhibited the highest LDH release into the media, reflecting a cytotoxicity of 57.22% at 5 µg/mL. This was followed by the lyophilized ammonium sulfate-precipitated A2 sample, which demonstrated 47.22% cytotoxicity at 6 µg/mL, and the acetone-precipitated B4 sample, which displayed 36.66% cytotoxicity at 5 µg/mL (Figure 9).

|

Figure 9: Cytotoxicity percentage as per LDH activity assay on HepG2 cells after purified L-methioninase treatment. |

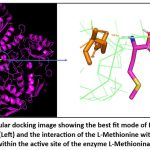

Docking Results

L-Methionine-L-Methioninase and L-Homocysteine-L-Methioninase were docked in nine modes, with the highest binding affinities of -4.7 kcal/mol and -4.2 kcal/mol, respectively, and an RMSD (both upper and lower bounds) of 0. The binding energy for methionine was higher than for homocysteine, indicating a stronger binding of methionine to L-Methioninase. The substrate L-Methionine formed interactions with Glutamine (GLN-534) and Histidine (HIS-1250) residues within the enzyme’s active site, with interatomic distances of 2.1 Å and 2.2 Å, respectively (Figure 10). Similarly, L-Homocysteine-L-Methioninase interacts with Lysine (LYS-1760), Arginine (ARG-1757), and Aspartic acid (ASP-718) residues of L-Methioninase, with an interatomic distance of 2.6 Å and 2.5 Å, respectively (Figure 11).

|

Figure 10: Molecular docking image showing the best fit mode of L-Methionine and L-Methioninase (Left) and the interaction of the L-Methionine with the amino acid residues within the active site of the enzyme L-Methioninase (Right). |

|

Figure 11: Molecular docking image showing the best fit mode of L-Homocysteine and L-Methioninase (Left) and the interaction of the L-Methionine with the amino acid residues within the active site of the enzyme L-Methioninase (Right). |

Discussion

Methionine is a non-negotiable, essential amino acid required for numerous primary tumors and human cancer cell lines. Normal cells, however, are largely resistant to exogenous methionine depletion.18 The phenomenon of methionine dependence has been studied extensively, although the exact mechanisms remain elusive. Nevertheless, many researchers have attempted to exploit the methionine dependency of tumors for therapeutic benefits in vivo. Methionine levels in plasma and tumors have been successfully reduced by both dietary and pharmaceutical interventions, and numerous animal tumors regressed upon a methionine-free diet or total parenteral feeding.

The use of methioninase enzyme is a well-established alternative method of depleting methionine. In preclinical models, this enzyme selectively degrades methionine and inhibits cancer growth. However, prolonged exposure could be harmful and affect the patient’s quality of life; therefore, methionine restriction may find greater application when combined with conventional chemotherapeutic agents.

To identify an efficient microbial L-methioninase with potential anticancer properties, we isolated microorganisms from diverse environmental sources. A total of 21 isolates were recovered on L-methionine medium and subsequently screened for L-methioninase activity. Based on their activity, two bacterial isolates (B4 and B6), a fungal isolate (F6), and an actinomycete isolate (A2) were selected for further studies. Culture supernatants from these isolates were tested against cancer cell lines, and isolates A2 and B4 demonstrated the highest cytotoxic effects on HeLa cells. Among these, B4 exhibited the highest specific activity of L-methioninase, followed by A2. 16S rRNA sequencing identified these two isolates as Pseudomonas plecoglossicida (B4) and Streptomyces cavourensis (A2).

The culture supernatants were further purified using ammonium sulfate and acetone precipitation methods. The ammonium sulfate-precipitated L-methioninase from P. plecoglossicida (JUB4) showed a 7.06-fold increase in specific activity, while the enzyme from S. cavourensis (JUA2) exhibited a 1.8-fold increase compared to their respective crude extracts. In contrast, acetone precipitation resulted in lower specific activities, validating ammonium sulfate precipitation as a more effective method for enzyme purification in this context. Previous reports have shown that L-methioninase from Candida tropicalis can be purified 34.19-fold using ion-exchange and gel-filtration chromatography.19

The crude L-methioninase from S. cavourensis (A2) and P. plecoglossicida (B4) inhibited the proliferation of HeLa and HepG2 cells, demonstrating their anticancer potential. Following purification by acetone precipitation, L-methioninase from both species showed enhanced cytotoxicity against HepG2 cells (a liver cancer cell line). Furthermore, ammonium sulfate-precipitated and lyophilized L-methioninase from both microbial sources exhibited the highest cytotoxic effects on HepG2 cells at 40 μg/mL. Higher or lower concentrations were less effective, indicating a clear dose-dependent cytotoxic effect. These observations were corroborated by LDH assay results, which revealed greater cytotoxicity for the acetone-precipitated enzymes, followed by the ammonium sulfate-purified enzymes.

Overall, our findings indicate that HepG2 cells were more sensitive to L-methioninase treatment than HeLa cells. A previous study reported in vitro antitumor activity of Candida tropicalis L-methioninase against human liver (HepG2), breast (MCF-7), and colon (HCT116) cell lines, where the IC₅₀ for the breast cancer cell line (MCF-7) was lower (0.13 U/mL) than for the liver cancer cell line (HepG2; IC₅₀ = 0.2 U/mL).19 Several studies have documented the ability of microbial L-methioninase to inhibit the growth of various tumor cell lines in both in vitro and in vivo models.20–25 For instance, Pseudomonas putida L-methioninase demonstrated greater cytotoxicity against leukemia than solid tumor cell lines, with IC₅₀ values of <0.5 U/mL for leukemia and 0.8–1.5 U/mL for lung and glioma cells.26 Similarly, Aspergillus flavipes L-methioninase showed potent activity against prostate (PC3), liver (HepG2), and breast (MCF-7) cancer cells, with IC₅₀ values of 0.001 U/mL, 0.26 U/mL, and 0.37 U/mL, respectively.4

In the present study, in silico docking revealed stronger binding of methionine to L-methioninase than homocysteine, supporting the hypothesis that microbial L-methioninase depletes methionine to exert anticancer effects. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report describing L-methioninase enzymes from P. plecoglossicida and S. cavourensis with promising anticancer properties. It is also the first study to report in silico docking of L-methioninase with methionine and homocysteine. However, these findings require further validation through in vivo studies using mouse models of liver and cervical cancer before clinical application can be considered.

Conclusion

In conclusion, two microbial isolates — Pseudomonas plecoglossicida JUB4 and Streptomyces cavourensis JUA2 — were identified as potent producers of L-methioninase with promising anticancer activity against liver cancer cells in vitro. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of L-methioninase from these species. These isolates hold significant potential as sources for further purification, detailed characterization, and in vivo validation studies.

Acknowledgement

The authors are thankful to Jain (Deemed-to-be University) for supporting with the necessary infrastructural facilities, and opportunity to carry out the current project work.

Funding Sources

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

This statement does not apply to this article.

Ethics Statement

This research did not involve human participants, animal subjects, or any material that requires ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not involve human participants, and therefore, informed consent was not required.

Clinical Trial Registration

This research does not involve any clinical trials.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

Not Applicable

Author Contributions

Varalakshmi Kilingar Nadumane: Conceptualization, Visualization, Supervision, Resources, Project Administration. Writing- Review, Editing & Final approval of the manuscript.

Deshoju Sneha, Riya Jain, Nagalakshmi Devaraju, Nuzhat Sheikh, and Zagade Akshay Sunil: Methodology, Data Collection, Analysis, Writing –original draft.

Suman Jangir: Methodology, Data Collection, Project Administration. Writing- Review & Editing.

References

- Harris CC. Structure and function of the p53 tumor suppressor gene: clues for rational cancer therapeutic strategies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996; 88(20): 1442–1455. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/88.20.1442

CrossRef - Swisher SG, Roth JA, Nemunaitis J, et al. Adenovirus-mediated p53 gene transfer in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999; 91(9): 763–771. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/91.9.763

CrossRef - Rani SA, Sundaram L, Vasantha PB. Isolation and screening of L-asparaginase producing fungi from soil samples. Int. J. Pharm. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2012; 4 (1): 279–282.

- El-Sayed AS, Shouman SA, Nassrat HM. Pharmacokinetics, immunogenicity and anticancer efficiency of Aspergillus flavipes L-methioninase. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2012; 51(4): 200–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enzmictec.2012.06.004

CrossRef - Mohkam M, Taleban Y, Golkar N, et al. Isolation and identification of novel l-Methioninase producing bacteria and optimization of its production by experimental design method. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2020; 26: 1878–1881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcab.2020.101566

CrossRef - Parry L, Clarke AR. The roles of the methyl-CpG binding proteins in cancer. Genes Cancer. 2011; 2(6): 618–630.

CrossRef - Kavya D, Nadumane VK. A combination of semi-purified L-methioninase with tamoxifen citrate to ameliorate breast cancer in athymic nude mice. Mol Biol Rep. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-022-08144-

CrossRef - Aneja KR. Experiments in Microbiology, Plant Pathology and Biotechnology. New Age Int.; 2007.

- Bopaiah BBK, Kumar DAN, Balan K, et al. Purification, characterization, and antiproliferative activity of L-methioninase from a new isolate of Bacillus haynesii JUB2. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2020; 10(10): 054–061.

- Sharma B, Singh S, Kanwar SS. L-methionase: a therapeutic enzyme to treat malignancies. Biomed Res Int. 2014; 2014:506287. doi: 10.1155/2014/506287.

CrossRef - Prerana V, Varalakshmi KN. Purification and Characterization of a Protease Inhibitor with Anticancer Potential from Bacillus endophyticusJUPR15. Curr Cancer Ther Rev. 2019; 15: 74-82.

CrossRef - Fic E, Kedracka-Krok S, Jankowska U, Pirog A, Dziedzicka-Wasylewska M. Comparison of protein precipitation methods for various rat brain structures prior to proteomic analysis. Electrophoresis. 2010;31(21):3573-3579. https://doi.org/10.1002/elps.201000197

CrossRef - Wingfield P. Protein precipitation using ammonium sulfate. Curr Protoc Protein Sci. 2001 May;Appendix 3:Appendix 3F. doi: 10.1002/0471140864.psa03fs13.

CrossRef - Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65(1-2):55-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4

CrossRef - Avelar-Freitas BA, Almeida VG, Pinto MC, et al. Trypan blue exclusion assay by flow cytometry. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2014;47(4):307-315. https://doi.org/10.1590/1414-431X20143437

CrossRef - Smith SM, Wunder MB, Norris DA, Shellman YG. A simple protocol for using a LDH-based cytotoxicity assay to assess the effects of death and growth inhibition at the same time. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e26908. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0026908

CrossRef - Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem. 2010;31(2):455-461. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.21334

CrossRef - Kavya D, Nadumane VK. Identification of highest L-methioninase enzyme producers among soil microbial isolates, with potential antioxidant and anticancer properties. J Appl Biol Biotechnol. 2020;8(6):21-27. https://doi.org/10.7324/JABB.2020.80604

CrossRef - Selim MH, Karm Eldin EZ, Saad MM, Mostafa ESE, Shetia YH, Anise AAH. Purification, characterization of L-methioninase from Candida tropicalis, and its application as an anticancer. Biotechnol Res Int. 2015; 2015:173140. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/173140

CrossRef - Kawaguchi K, Han Q, Li S, et al. Targeting methionine with oral recombinant methioninase (o-rMETase) arrests a patient-derived orthotopic xenograft (PDOX) model of BRAFV600E mutant melanoma. Cell Cycle. 2018;17(3):356-361. https://doi.org/10.1080/15384101.2017.1405195

CrossRef - Sundar WA, Nellaiah H. Production of methioninase from Serratia marcescens isolated from soil and its anti-cancer activity against Dalton’s lymphoma ascitic (DLA) and Ehrlich ascitic carcinoma (EAC) in Swiss albino mice. Trop J Pharm Res. 2013; 12:699-704.

CrossRef - Hu J, Cheung NKV. Methionine depletion with recombinant methioninase: in vitro and in vivo efficacy against neuroblastoma and its synergism with chemotherapeutic drugs. Int J Cancer. 2009;124(7):1700-1706.

CrossRef - Tan Y, Xu M, Hoffman RM. Broad selective efficacy of rMETase and PEG-rMETase on cancer cells in vitro. Anticancer Res. 2010;30(3):793-798.

- Salim N, Santhiagu A, Joji K. Purification, characterization, and anticancer evaluation of L-methioninase from Trichoderma harzianum. 3 Biotech. 2020; 10:501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-020-02494-w

CrossRef - Kavya D, Varalakshmi KN. Enhanced L-methioninase production by Methylobacterium sp. JUBTK33 through RSM and its anticancer potential. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2023; 47:102621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcab.2023.102621

CrossRef - Hori H, Takabayashi K, Orvis L, Carson DA, Nobori T. Gene cloning and characterization of Pseudomonas putida L-methionine-α-deamino-γ-mercaptomethane-lyase. Cancer Res. 1996;56(9):2116-2122.

Abbreviations List

ANOVA: analysis of variance

DTNB: 5,5′-Dithiobis-(2-Nitrobenzoic Acid)

LDH: Lactate dehydrogenase

MGL: L-Methionine-γ-lyase

MTL: Methanethiol

MTT: (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

NAD: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

NADH: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide hydride

PBS: phosphate buffered saline

PLP: pyridoxal phosphate

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.