Manuscript accepted on : 04-07-2025

Published online on: 10-09-2025

Plagiarism Check: Yes

Reviewed by: Dr. Gopal Samy

Second Review by: Dr. Mohamed Nader

Final Approval by: Dr. Ali Elshafei

Hameim Yahya1 , Ameer Hamza1

, Ameer Hamza1 , Mohd Anas1

, Mohd Anas1 , Shahid Khan Alvi2

, Shahid Khan Alvi2 , Alvia Farheen2

, Alvia Farheen2 and Mudassir Alam3*

and Mudassir Alam3*

1Interdisciplinary Nanotechnology Centre (INC), Z. H. College of Engineering and Technology, Aligarh Muslim University, AMU, Aligarh, UP, India

2Department of Zoology, Faculty of Life Sciences, Aligarh Muslim University, AMU, Aligarh, UP,, India

3Department of Biological Sciences, Indian Biological Sciences and Research Institute (IBRI) Noida, UP, India

Corresponding Author:Email - syedalamalig@gmail.com

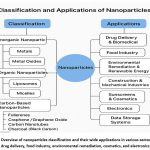

ABSTRACT: Nanoparticles have been established as a transformative material with exceptional physicochemical features. The extremely small size and their ability to surface modifications have facilitated their utilization in an extensive array of applications. Nanoparticles can be classified based on their compositions which include inorganic, organic, and carbon-based variants. Inorganic nanoparticles can be further categorized into metal-based, metal oxide-based, and doped metal-based. The organic nanoparticles comprise liposomes and micelles that are well recognized and extensively explored for their biocompatibility and targeted drug delivery potential. Carbon-based nanostructures such as graphene, fullerenes, carbon nanotubes, and nanofibers are discussed for their diverse functionalities and wider applications in various fields. The utilization of nanoparticles has revolutionized many sectors with their wide-range applications, and their pivotal role in drug delivery and biomedicine has left a remarkable impression. In the food industry, nanoparticles are utilized for improved packaging, preservation, and nutrient delivery. Their applications in environmental remediation include pollutant degradation and water purification. Additionally, they are incorporated into mechanical industries and construction materials to impart strength and durability. The cosmetic and sunscreen industries exploit nanoparticles for enhanced skin absorption and UV protection, while their integration into electronics and data storage systems supports the development of faster, smaller, and high-efficiency devices. Overall, this review provides an integrative perspective on the diverse classifications and multifaceted role of nanoparticles.

KEYWORDS: Drug delivery; Environmental remediation; Inorganic nanoparticle; Organic nanoparticle; Theranostic

| Copy the following to cite this article: Yahya H, Hamza A, Anas M, Alvi S. K, Farheen A, Alam M. An Extensive Overview of Nanoparticle Classification, their Applications and Emerging Horizons in Nanotechnology. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(3). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Yahya H, Hamza A, Anas M, Alvi S. K, Farheen A, Alam M. An Extensive Overview of Nanoparticle Classification, their Applications and Emerging Horizons in Nanotechnology. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(3). Available from: https://bit.ly/46vbAeX |

Introduction

Nanotechnology is an emerging arena of science and engineering that focuses on nanoscale materials and architectures, usually ranging from 1 to 100 nanometers. The small size, distinctive characteristics, and unique features of nanoparticles (NPs) allow researchers and engineers to modulate and design them for utilization in numerous applications.1 The multidisciplinary field of nanotechnology lies at the intersection of engineering, biology, chemistry, and physics. The word “nano” denotes a billion-fold decrease, using SI units (1 nm being equivalent to 10^9). In 1959 the Novel Prize winner Richard P Feynman first time introduced the concept of Nanotechnology when he delivered a talk titled “There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom”. During his talk, he discussed the feasibility of creating materials via direct atomic manipulation. In 1974, Norio Taniguchi was the first person who use the word “nanotechnology” to the first time to describe precision engineering at the nanoscale. Drexler was inspired by Feynman’s concepts. Drexler established the Foresight Institute in 1986 to enhance the general public’s comprehension of nanotechnology concepts and their implications. Since then, there have been numerous revolutionary and advanced developments in the field of nanotechnology.2 The rapid growth and utmost acceptance of nanotechnology have withdrawn the attention of researchers all over the world. With advancements in science and technology, the scientific community embraces technologies and products that are relatively less expensive, safe, and more environmentally friendly than earlier technologies. Additionally, they are concerned about the financial standing of technologies due to the excessive depletion of natural resources worldwide.3

Nanotechnology offers transformative potential across diverse sectors, including electronics, healthcare, materials science, and energy, enabling groundbreaking solutions to global challenges. This field facilitates the creation of novel materials, devices, and systems with exceptional precision and efficiency.4 Surface effects and quantum effects are the two primary factors that lead to nanomaterials (NMs) displaying substantially different behavior compared to larger-scale materials. These characteristics cause NMs to display enhanced or unique thermal, magnetic, electronic, and catalytic properties.5 NMs show unique surface effects compared to micromaterials or bulk materials for three key reasons: (a) they possess significantly high surface area and a greater number of particles per unit mass, (b) there is an increased percentage of atoms on the surface of NMs, (c) surface atoms in NMs have fewer neighboring atoms. Due to these variations, the chemical and physical characteristics of NMs differ from those of their larger-sized counterparts. For instance, having a reduced number of neighboring atoms directly touching the surface atoms causes the binding energy per atom to decrease in NMs. This alteration directly affects the melting temperature of nanomaterials, as described by the Gibbs-Thomson equation; for instance, 2.5 nm gold nanoparticles (GNPs) have a melting point 407 degrees lower than that of bulk gold.6 NMs with greater surface areas and higher surface-to-volume ratios tend to display higher reactivity because of their expanded reaction surfaces.7 NMs classified as zero-dimensional (0-D) have dimensions that fall within the nanoscale in all three directions. Quantum dots and fullerenes are the examples. One-dimensional NMs (1-D): these materials have one dimension that exceeds the nanoscale within this category. Nanofibers, nanorods, nanotubes, and nanowires are some examples. Two-dimensional NMs (2-D): these NMs possess two dimensions beyond the nanoscale. Nanofilms, nanosheets, and nanolayers are all examples. Three-dimensional NMs (3-D) NMs: In this category, the materials do not have size limitations in any dimension.8 The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) defines NPs as nano-objects with all external dimensions in the nanoscale, where the longest and shortest axes show no significant variation. NPs may have a spherical, cylindrical, conical, tubular, hollow core, spiral shape, or be irregular. When NPs are smaller than 1 nm in size, they are typically referred to as atom clusters. NPs may exist in either crystalline form composed of single or multiple crystals, or in an amorphous state. NPs may exist in an unbound state or clumped together.9 NPs can be homogeneous or can consist of multiple layers. Nanoparticles are generally structured in three distinct layers: (a) an outer layer consisting of small molecules, metal ions, surfactants, or polymers; (b) a middle shell layer, composed of a material distinct from the core; and (c) an inner core layer, located at the nanoparticle’s center.

Recent research has highlighted the classification of NPs based on their composition, shape, and synthesis method. For instance, they can be classified into organic, inorganic, and carbon-based types, with metal-based nanoparticles such as gold (Au), silver (Ag), and iron (Fe) being extensively researched for their remarkable properties and diverse applications across multiple disciplines.10 A comprehensive database has been constructed that includes over 700 unique NMs and thousands of data points related to their physicochemical properties and bioactivities. This resource supports predictive modeling for critical endpoints such as cellular uptake and zeta potential, enabling researchers to design NMs with desired characteristics more efficiently.11 The applications of NPs are vast and increasingly significant across multiple domains. In medicine, NPs are revolutionizing drug delivery systems; for example, GNPs are utilized for targeted cancer therapy due to their ability to enhance imaging and treatment efficacy.12,13 They can be engineered to carry diverse substances, including targeting or imaging components and therapeutic compounds. Also, they can combine diagnostics, targeting, treatment, and monitoring, which conquer the challenges linked to conventional diagnostic and treatment methods. This facilitates the simultaneous administration of imaging and therapeutic agents at a single location, allowing for real-time monitoring of their effects.14 Environmental applications include the use of nanoscale zero-valent iron for groundwater remediation, effectively degrading pollutants.15 Moreover, NPs play a crucial role in materials science by improving the mechanical properties of composites and coatings, as well as in electronics where they contribute to the miniaturization of components.16 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) is actively researching the environmental fate and transport of engineered NMs to assess their potential risks and benefits.17 As the field continues to evolve, ongoing data-driven research is essential for advancing our understanding of NMs unique behaviors and optimizing their applications in technology and medicine. The composition, classification, and diverse applications of NPs highlight their significance in contemporary science and technology.

|

Figure 1: Overview of nanoparticles classification and their wide applications in various sectors such as drug delivery, food industry, environmental remediation, cosmetics, and electronics |

Classification of Nanoparticles

Inorganic Nanoparticles

Inorganic nanoparticles (INPs) do not contain carbon. Metals and their oxides are the primary sources of INPs. When compared to organic nanoparticles, INPs have great utilization in research. They offer the advantage of being hydrophilic, safe, and compatible with living system.10

Nanoparticles based on metals

Metals like Iron (Fe), cadmium (Cd), aluminum (Al), silver (Ag), gold (Au), copper (Cu), cobalt (Co), zinc (Zn), and lead (Pb) are frequently used to make metal nanoparticles (MNPs). The most common metals used to make nanoparticles are Zn, Ag, Cu, Fe, and Au. Owing to their documented localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) characteristics, these nanoparticles show distinct optoelectronic properties and exhibit a wide absorption zone in the visible region of solar electromagnetic range.1 Transition metals have half-filled d-orbitals that enhance their redox reactivity, making them highly valuable for the synthesis of MNPs.18 MNPs can be produced through physical, chemical, and biological approaches. Biodegradable, non-toxic, and biologically derived nanoparticles are widely utilized across various sectors, such as biomedicine, environmental management, cosmetics, drug delivery, food safety, healthcare, and optics.19 MNPs exhibit remarkable ultraviolet-visible sensitivity, enhanced electrical and catalytic activities, and antibacterial properties, owing to their quantum confinement effects and exceptional surface area-to-volume ratio. MNPs like Au and Pt are also used to make catalysts that are frequently utilized in a variety of chemical reactions and sensors due to their vast surface area that can absorb reactants.20 At present, MNPs such as Ag, Au, Pt, TiO2, and ZnO are being used as primary antibacterial agents. These are predominantly utilized in the field of biomedicine due to their prolonged steadiness and exceptional biocompatibility. Research has shown that metal-based nanoparticles possess bactericidal properties, effective against both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria.21 MNPs are believed to have antimicrobial properties due to their small size and large surface area-to-volume ratio, which allow their entry into bacterial membranes. When NPs interact with microorganisms inside cellular machinery, they hinder enzyme activities, disrupt proteins, hamper electrolyte balance, trigger oxidative stress, and alter gene expression.22

Nanoparticles based on Metal oxides

Metal oxide nanoparticles (MONPs) are chemically stable due to their oxidation resistance. Moreover, they have a lower density than their corresponding metals, and these characteristics could help address the problem of sedimentation in the nanofluid formulation. MONPs are now recommended as a nano additive for inclusion in nanofluid systems, despite their lower heat transfer capabilities compared to metals.23 Al2O3, CuO, MgO, ZrO2, CeO2, TiO2, ZnO, and Fe2O3 are commonly utilized nanoparticles within metal oxides, due to their distinctive physical and chemical characteristics.24 Numerous researchers have utilized CuO nanoparticles as additives for their excellent tribological characteristics and eco-friendly nature.25 Generally, MONPs are typically developed to modify the properties of their metal-based counterparts. To harness their improved efficiency and reactivity, they are extensively synthesized. NPs that are formed by transition metal oxides are widely used in making rechargeable batteries with high storage capacity.26 The role of MONPs has been researched extensively in biomedicine and has shown outstanding outcomes. Several MONPs including Ag2O, FeO, MnO2, CuO, Bi2O3, ZnO, MgO, TiO2, CaO, and Al2O3 have been recognized for their strong antibacterial effects.27 A study examined the effects of Ag2O nanoparticles and suggested them as an innovative antibiotic source.28 Additionally, another study showed that Ag2O nanoparticles have antimicrobial effects on Escherichia coli.29 The ZnO nanoparticles demonstrated effective antimicrobial effects against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria as well as spores.30 A study by Azam et al. examined comparative antibacterial properties of CuO, ZnO, and Fe2O3 nanoparticles on gram-negative bacteria including E. coli and P. aeruginosa, as well as gram-positive bacteria like Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus subtilis. ZnO NPs exhibited strong antimicrobial properties in the study, while Fe2O3 NPs had minimal impact on bacterial growth.31 Numerous studies have shown the antifungal activity of TiO₂ nanoparticles against fungal biofilms. The results indicated that the synthesized TiO₂ NPs exhibited enhanced antifungal effects on Candida albicans biofilms.32, 33 MnO2 NPs are viewed as a perfect compound due to their extraordinary physicochemical and structural-based characteristics. The outstanding layout of MnO2 NPs in 2D format is highly significant for medical uses. They researched MnO2 nanosheets and investigated their potential in imaging, biosensing, cancer therapy, and molecular adsorption. The results indicated that the MnO2 nanosheets exhibit lower toxicity and greater compatibility with blood and tissues.34 A study by Ahamed et al. revealed that CuO nanoparticles showed significant antimicrobial effects on various bacterial strains including E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterococcus faecalis, Salmonella typhimurium, and Staphylococcus aureus.35 The antibacterial properties of CaO and MgO NPs have also shown great excellence in antibacterial studies. It can be made inexpensively using readily accessible materials and possesses outstanding biocompatibility.

Doped metal based Nanoparticles

Scientists are currently concentrating on altering NMs to enhance their stability during chemical processing and ensure their safety for the environment. Doped metal nanoparticles (DMNPs) are formed by introducing metals into a pre-existing cluster. The incorporation of metals into a material is referred to as doping, resulting in the formation of a doped cluster. The metal atom that is incorporated is called a dopant or foreign atom.36 DMNPs change the attributes of NPs to enhance their properties and make them suitable for a range of applications. DMNPs have shown great promise in biomedical applications.37 Doping ZnO nanoparticles with Sb or Mg can enhance antibacterial activity. It was recommended to utilize DMNPs in various pharmaceutical applications due to their lower toxicity concerns.38 In their 2015 study, Guo et al. examined how tantalum-doped zinc oxide nanoparticles affect gram-positive bacteria such as B. subtilis, S. aureus, and gram-negative E. coli and P. aeruginosa. In ambient darkness, the NPs doped with Ta and ZnO demonstrated increased antimicrobial activity compared to ZnO. The incorporation of Ta5+ ions into ZnO NPs enhanced surface bioactivity and intensified electrostatic interactions. Findings showed improved antibacterial properties with the use of 5% doped NPs compared to pure metal oxide NPs.39 Dhanasekar et al. (2018) presented Cu-doped TiO2 NPs with reduced graphene oxide (rGO) serving as the solid support, later it was employed as a cutting-edge mild antibacterial agent. The findings indicated that by incorporating rGO, the nanoparticles of Cu2O-TiO2 exhibited enhanced visible light antimicrobial capabilities. This was evident through larger inhibition zones and lower minimum inhibitory concentrations for both gram-positive and gram-negative microorganisms when compared to pure TiO2.40

Organic Nanoparticles

Organic nanoparticles (ONPs) are extensively utilized in numerous medical research applications due to their small size, similar to proteins, and because they are mostly made up of carbon compounds that are less than 100 nm. Organic molecules such as liposomes, micelles, ferritin, aptamers, and dendrimers, are used to create ONPs. These organic nanoparticles are frequently used to make medicines due to their incredibly small diameter.41 Micelles and liposomes are two types of nanoparticles that are susceptible to electromagnetic radiation (heat and light) and have an empty core called a nanocapsule.42

Liposomes

Liposomes are spherical organic nanoparticles that are composed of one or more phospholipid bilayers that encapsulate an aqueous core. Liposomes work as ideal carriers for both hydrophilic and hydrophobic drug candidates. It was first introduced in the year 1960, and since then, it evolved as one of the most widely researched and clinically applied nanocarriers, mainly in drug delivery, vaccine formulation, and gene therapy.43 Their ability to enhance drug bioavailability and enable targeted delivery has been well documented. Recent advances include the development of stimuli-responsive liposomes such as pH-sensitive, temperature-sensitive, and enzyme-triggered systems that release their payload specifically at the disease site, improving therapeutic efficacy and minimizing side effects.44 For instance, a study demonstrated a pH-sensitive liposomal system for targeted doxorubicin delivery in tumor tissues, showing enhanced cytotoxicity in acidic microenvironments.45 Another recent innovation involves PEGylated liposomes, which improve circulation time by evading immune detection, as seen in the success of Doxil®, the first FDA-approved liposomal drug.46 Moreover, liposomes are increasingly being integrated with imaging agents for theranostic applications, which help in simultaneous diagnosis and therapy.47 Additionally, liposomes have also been used in mRNA vaccines such as COVID-19 vaccines, this suggests their translational potential.48

Micelles

Micelles are self-assembled colloidal structures formed by amphiphilic molecules typically surfactants or block copolymers that arrange themselves in aqueous environments with a hydrophobic core and hydrophilic shell. This unique architecture allows micelles to effectively solubilize poorly water-soluble drugs and protect them from enzymatic degradation, thus, making them valuable in the delivery of drugs, particularly in the case of cancer therapy and inflammatory diseases.49 The nanosize of micelles facilitates passive targeting via enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect. Recent research emphasizes the development of stimuli-responsive micelles, which disassemble and release their therapeutic payload against specific stimuli like pH, temperature, redox gradients, or enzymes present in tumor microenvironments.50 For example, a study reported pH/redox dual-responsive polymeric micelles for precise doxorubicin delivery in acidic and glutathione-rich cancer tissues, significantly enhancing antitumor efficacy and reducing systemic toxicity.51 Furthermore, polymeric micelles such as those formed from polyethylene glycol (PEG)-block-polycaprolactone (PCL) or PEG-block-polylactic acid (PLA) have been extensively explored because of their stability and capability to encapsulate a variety of drugs.52 Innovations in active targeting have also emerged, with ligands such as folic acid or peptides grafted onto micelle surfaces to target specific receptors overexpressed in cancer cells.53 A study highlighted how multifunctional micelles co-delivering chemotherapeutic agents and siRNA are being designed for combination therapies.54 Micelles offer a versatile, tunable, and sophisticated platform for next-generation nanomedicine.

Carbon Derived Nanoparticles

Carbon-based nanoparticles (CBNPs) are a diverse group of materials built from carbon atoms, exhibiting unique properties due to their nanoscale dimensions and structure. With the help of various synthesis methods, a variety of carbon-centric NMs have been synthesized in recent years, each with special qualities and uses. Carbon-based NMs possess numerous potential applications in biological fields, which include drug delivery, wastewater treatment, energy production, storage, and biological data storage.55

Fullerenes

The most recognized and often used fullerene is Buckminsterfullerene (C60). It consists of 60 carbon atoms, each forming three bonds, arranged in a cage-like structure resembling a soccer ball.56 Recently, a wide range of applications in nanoscience and nanotechnology have made use of fullerene-based nanostructures, such as nanorods, nanotubes, and nanosheets. Because of its versatility, fullerene can be applied in a variety of ways to accelerate the reactions of a broad spectrum of chemicals.57 An in-vitro study revealed that water-soluble C60 decreased the production of matrix-degrading enzymes in chondrocytes derived from osteoarthritis patients when stimulated by interleukin-1 β (IL-1 β) or hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Concurrently, C60 markedly enhanced the synthesis of proteoglycan and collagen type II while mitigating cell apoptosis and senescence under catabolic stress conditions. In the corresponding in vivo study, intra-articular administration of C60 effectively slowed cartilage degradation in an osteoarthritis rabbit model in a dose-dependent manner. The observed protective effects of C60 were potentially attributed to its free radical scavenging properties.58,59

Graphene and Graphene Oxide

Graphene has a two-dimensional layer made of carbon atoms that are organized in a hexagonal shape structure. It is a substance that is fundamental to the construction of several kinds of nanoparticles made of carbon.60 Because of graphene and graphene oxide (GO) strength, wide surface area, and nanosize, its application in the field of nanotechnology is now driving significant innovation. Polymer nanocomposite materials can be fabricated by using a graphene and graphene oxide which exhibit superior mechanical, electrical, and thermal, anti-corrosion properties as well as a molecular barrier.61 Several case studies have investigated the effectiveness of GO in eliminating emerging pharmaceutical contaminants from water. For example, Banerjee et al. reported that GO could function as a suitable adsorbent for large-scale treatment of water contaminated with pharmaceuticals like ibuprofen and other anti-inflammatory drugs.62 Another study demonstrated the effectiveness of GO/single-walled carbon nanotube composite membranes (GO-SWCNT BPs) in removing non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), including diclofenac, ketoprofen, and naproxen.63

Carbon Nanotubes

One of the most versatile forms of the carbon allotrope is carbon nanotubes (CNTs) were discovered by S. Iijima in the year of 1991. They are long, cylindrical, and tubular structures made of graphene layers that have been wrapped into cylindrical shapes. Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) consist of a single layer of carbon atoms with a diameter of approximately 3 nm, whereas multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) are composed of multiple concentric layers of carbon atoms and have a diameter of less than 100 nm. CNTs have unique remarkable properties including high strength, stiffness, high elasticity, and excellent electrical and thermal conductivity.64 CNTs including SWCNTs and MWCNTs serve various functional purposes; they are frequently utilized in composite materials, electronics, energy storage, biomedical, catalysis, and environmental remediation. Yu et al. introduced a novel 3D printing technique to fabricate CNT-based micro-supercapacitors using CNT-infused ink. The resulting micro-capacitors exhibited notable stability and substantial areal capacitance.65 Ye et al. developed CNT-reinforced thermoplastic polyimide composites by producing filaments intended for aerospace applications and analyzing their tensile and bending properties. The study revealed that the CNT-reinforced composites demonstrated improved mechanical performance, suggesting that with further refinement, they could be utilized to manufacture complex aerospace components.66

Carbon Based Nanofiber

Carbon nanofibers (CNFs) are hollow core nanofibers structures composed of one or two graphite layers oriented in a certain way, either parallel to or at right angles to the fiber’s central axis. Carbon nanofiber has unique electric conductivity and mechanical, and thermal properties. The average range of their diameter is 10 nm to 200 nm. Because of this, CNFs are deployed in different domains, including drug delivery, sensors, photocatalysis, energy devices, and nanocomposites.67 CNFs can be synthesized through various techniques, including electrospinning, chemical vapor deposition (CVD), and templated synthesis. One approach involves producing polymer nanofibers (PNFs) through electrospinning, followed by high-temperature carbonization to convert them into CNFs.68 Zhang and colleagues described the production of electrospun carbon nanofibers (ECNFs) derived from polyacrylonitrile (PAN) for applications in energy conversion, catalysis, sensing technologies, adsorption and separation processes, as well as in the biomedical field.69 Feng et al. examined the synthesis method, characteristics, and applications of CNFs along with their pre-synthesized composites70, while Kim et al. showcased developments in electrospun CNFs for electrochemical energy storage applications.71 Collectively, these studies furnish valuable insights into the utilization of produced CNFs and CNF-based composites across diverse fields.

Table 1: The table summarizes nanoparticle categories, Sub-categories, and their descriptions with common applications

| Category | Sub-category | Description | Examples/Applications |

| Inorganic Nanoparticles | |||

| Metal containing nanoparticles | Pure metal particles at the nanoscale exhibit plasmonic and catalytic properties. | Gold (Au), Silver (Ag), and Platinum (Pt) NPs; are used in biosensing and drug delivery. | |

| Metal oxidescontaining

nanoparticle |

Metal oxide-based nanomaterials with photocatalytic, magnetic, or antimicrobial effects. | Zinc oxide (ZnO), Titanium dioxide (TiO₂), and Iron oxide (Fe₃O₄); are used in sunscreens and remediation. | |

| Doped metal-based nanoparticles | Metal/metal oxide nanoparticles doped with other elements to enhance properties. | Al-doped ZnO, Mn-doped Fe₃O₄; used in catalysis, and biomedical imaging. | |

| Organic Nanoparticles | |||

| Liposomes | Phospholipid bilayer vesicles are used as carriers for drugs or vaccines. | Liposomal doxorubicin; mRNA vaccine delivery. | |

| Micelles | Amphiphilic molecules forming spherical structures ideal for hydrophobic drug delivery. | Polymeric micelles for anticancer drugs. | |

| Carbon-based Nanoparticles | |||

| Fullerenes | Spherical carbon molecules (C60, C70) with antioxidant and electronic properties. | Used in photovoltaics, drug delivery, and lubricants. | |

| Graphene and Graphene Oxide | Single-layer carbon sheet (graphene) or oxidized version (GO) with high conductivity. | Sensors, batteries, water purification, drug delivery. | |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Cylindrical tubes with exceptional mechanical strength and conductivity. | Used in nanoelectronics, gene delivery, and composite materials. | |

| Carbon Nanofibers | Fibrous carbon nanostructures with high surface area and conductivity. | Used in energy storage, tissue engineering, and filtration systems. |

Uses of nanoparticles in different sectors

Drug Delivery and Biomedical

NPs use in drug delivery and biomedical applications has completely revolutionized therapeutic strategies. It offers targeted, efficient, and controlled release systems. Recent studies highlight that NPs such as liposomes, dendrimers, polymeric nanoparticles, and metallic nanocarriers (e.g., gold and silver nanoparticles) have demonstrated significant potential in enhancing drug bioavailability and reducing systemic toxicity.72 According to a published study in the year 2023 reports that nanoparticle-based delivery systems have shown a 50–70% improvement in therapeutic efficacy in cancer models compared to conventional drug administration.73 A study demonstrated that lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles achieved over 85% encapsulation efficiency and prolonged circulation time, significantly improving the delivery of siRNA for gene silencing in vivo.74 Moreover, the integration of stimuli-responsive nanoparticles triggered by pH, temperature, or enzymatic activity has enabled precise spatial and temporal control over drug release, as reported by several studies.75 In biomedical imaging and diagnostics, GNPs functionalized with antibodies have been employed for enhanced imaging contrast and early tumor detection, with sensitivity improvements of up to 60%, as reported in theranostics.76 Additionally, recent progress in the development of biodegradable and biocompatible NMs, such as chitosan and PLGA (poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)), has addressed concerns about long-term toxicity and environmental impact, paving the way for their clinical translation.77 The tumor microenvironment (TME) of solid tumors continues to be a significant obstacle to effective therapeutic strategies in cancer treatment. TME includes not only tumor cells but also various normal cells like natural killer (NK) cells, T cells, fibroblasts, macrophages, dendritic cells, and adipocytes.78 Consequently, these intricate elements of TME continue to pose a challenge that hinders tumor immunotherapy. Nonetheless, NPs could be flexible, efficient, and suitable agents to integrate with tumor immunotherapy. For example, tumor expansion and angiogenesis might trigger MDSCs and Tregs to release VEGF and TGF-β, leading to hypoxia and immune suppression.79 Research has shown that NPs are capable of selectively interacting with specific cells and molecules to transform the immunosuppressive environment into a normal immune response, thereby restoring the sensitivity of tumor cells to therapeutic interventions. Certain nanoparticles were also noted to accumulate in tumor tissue relative to normal cells, influenced by irregular lymphatic drainage, enhanced EPR effects, and permeable blood vessels. Moreover, NPs can be easily altered to bond with particular ligands, improving their efficiency.80 Another approach may be the Integration of cellular membranes into nanoparticles, which may enhance their concentration in cancer tissues. NPs encased in membranes sourced from a patient’s cancer cells adhere homotypically to cancer cell lines derived from the same patient; discrepancies between the donor and host lead to ineffective targeting.81 NPs encased in macrophage or leukocyte membranes identify tumors, and hybrid membranes, like those formed from erythrocyte–cancer cell combinations, can enhance specificity even further. NPs employing these membranes exhibit a twofold to threefold enhancement in drug activity compared to free drug.82 Likewise, the characteristics of materials can lead to NPs selectively accumulating in specific tissues. For instance, a poly(β-amino-ester) (PBAE) terpolymer/PEG lipid conjugate was refined for lung targeting, resulting in effectiveness two levels higher than the pre-optimized version under both in-vitro and in-vivo settings.83

Food Industry

Nanotechnology offers wide-ranging applications within the food industry, impacting areas like food processing, packaging, and the safety of products. It can improve food quality, enhance shelf life, detect contaminants, and even aid in delivering nutrients more effectively.84 Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) are also employed to enhance texture and food materials quality while packing and also protect the food from moisture and gases. Due to its antimicrobial activity, it prevents the growth of foodborne pathogens such as bacteria, parasites, and viruses.85 A nanocomposite coating can directly incorporate antimicrobial agents onto the coated film surface during food packaging. This can be achieved by integrating antimicrobial agents such as AgNPs or essential oils into the nanocomposite material, which allows for a controlled release and long-lasting protection against microbial growth.86 Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) are also used to detect the presence of pathogens in food packaging items. A study demonstrated that functional absorbing pads containing immobilized ZnONPs effectively inactivated Campylobacter jejuni in raw chicken meat. Specifically, pads with 0.856 mg/cm² of ZnO NPs reduced C. jejuni from approximately 4 log CFU/25 g to undetectable levels, following three days of storage at 4°C. Scanning electron microscopy confirmed that the nanoparticles did not migrate onto the meat surface, ensuring safety. The antimicrobial action was attributed to the controlled release of Zn²⁺ ions in acidic conditions and the generation of reactive oxygen species, which compromise bacterial cell integrity.87 Additionally, another study evaluated a nanocomposite of ZnO NPs with Aloe vera gel applied to chicken fillets. The treatment led to a great reduction in Salmonella typhi and Salmonella paratyphi.88 These studies suggest not only enhanced antimicrobial efficiency but also sustained biocompatibility and shelf life.

Environmental Remediation and Renewable Energy

Nanoparticles play a transformative role in both environmental remediation and renewable energy, which offer innovative solutions to persistent global challenges. In environmental remediation, NPs are employed to purify water, pollutants removal, and restoration of contaminated ecosystems. For example, lignin NPs derived from biomass have demonstrated great potential in adsorbing heavy metals and organic contaminants from water sources.89 Moreover, green-synthesized NPs are utilized in water purification and pollutant detection that actively contribute to sustainable environmental practices.90 Studies reported that AgNPs have been widely employed as water disinfectants because of their antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral properties. Their effectiveness stems from their potential to interfere with the cell walls and membranes of microorganisms, as well as interact with their DNA and proteins that ultimately disrupt their functions and prevent replication procedure.91 In same way, Titanium dioxide (TiO2) NPs aid in the extraction of heavy metals from water surfaces through solid-phase extraction. This technique is also suitable for environmental remediation and the purification of surface water.92 A 2024 study published in Scientific Reports by Kholief et al. synthesized TiO₂ NPs from ilmenite using leaching agents such as HCl, HNO₃, and Aqua Regia. The synthesized TiO₂ NPs were subjected to characterization through standardized techniques like XRD, SEM, and TEM which exhibited particle size of 92 nm, and demonstrated high photocatalytic efficiency in degrading organic pollutants under UV light. The TiO₂ NPs in combination with ferric chloride and chitosan achieved removal efficiencies of up to 99.7% for BOD, 99.6% for COD, and 94.9% for total Kjeldahl nitrogen, which suggests their potential for advanced wastewater treatment applications.93 In the domain of renewable energy, NPs have been reported to enhance the efficiency and functionality of energy systems. For instance, GNPs applications have shown enhanced solar cell performance by increasing sunlight absorption, which boosted electricity generation by several folds. Furthermore, advancements in NMs have led to upgraded energy storage solutions such as enhanced battery technologies and supercapacitors, which are crucial for the reliable supply of renewable energy.94

Mechanical Industries and Construction

Nanoparticles are increasingly being utilized in mechanical industries and construction sectors to enhance material performance, durability, and functionality. In mechanical industries, nanoparticles such as carbon nanotubes (CNTs), silicon carbide (SiC) NPs, and alumina (Al₂O₃) NPs are incorporated into lubricants and coatings to reduce friction, wear, and corrosion, significantly extending machinery life and improving efficiency. For instance, Silicon carbide (SiC) NPs addition to lubricants can significantly improve wear resistance. It is well well-known that even a low concentration of SiC NPs can lead to a substantial increase in wear resistance, often by over 40%.95 NMs are utilized in the construction industry to create stronger, longer-lasting cement, coatings that protect against corrosion, high-performance insulation materials, and sophisticated filtration systems.96 Certain nanoparticles may serve as cement binders that are used to increase yields and subsequently reduce expenses of the construction industry. From environmental, economic, and quality viewpoints, NMs add functional features to conventional housing construction techniques. For instance, incorporating nano silica (SiO2) and nano alumina (Al2O3) may enhance the durability and strength of cement-based structures by as much as 20%.97 Similarly, Hematite (Fe2O3) NPs also used to increase the concrete strength. Studies have shown that adding Fe2O3 NPs to concrete can increase compressive strength. This is primarily because the nanoparticles help to increase the rate of cement hydration and modify the pore structure of the concrete, leading to a denser and stronger material.98 Semiconducting NMs like TiO2 and various photocatalysts added during concrete preparation can self-purify the environment and facilitate the photodegradation of gases such as nitrogen oxides (NOx), carbon oxides (COx), and other indoor pollutants.99 Nanoclay has been utilized to enhance the mechanical properties of concrete by reducing permeability and shrinkage, resulting in a lower likelihood of cracking and harm to building structures.100

Sunscreens and Cosmetics

Nanoparticles are commonly used in sunscreens and cosmetics to enhance UV protection, improve stability, and create transparent formulations. Nano-based formulations have significantly contributed to the personal care industry. Among the most commonly used nanoparticles in sunscreens are zinc oxide (ZnO) and titanium dioxide (TiO₂), which offer broad-spectrum UV protection by scattering and absorbing ultraviolet radiation.101 When reduced to the nanoscale (typically 20–100 nm), these particles become transparent on the skin, eliminating the white, chalky appearance associated with traditional sunscreens, while still providing effective sun protection. This has greatly improved cosmetic acceptability and user compliance. In cosmetics, nanoparticles enhance texture, stability, and delivery of active ingredients. Lipid-based nanoparticles (solid lipid nanoparticles and nanostructured lipid carriers) are used to deliver vitamins (like A, E, and C), antioxidants, and anti-aging agents deeper into the skin, increasing their bioavailability and efficacy. Nanosomes, nanoemulsions, and nanocapsules are also employed to deliver fragrances, moisturizers, and pigments in a controlled manner, improving product longevity and uniformity.102 Recent studies have focused on the safety, skin penetration, and environmental impact of these nanoparticles. For instance, a study examined the dermal penetration of TiO₂ and ZnO nanoparticles and concluded that while they largely remain on the skin surface or within the stratum corneum, long-term exposure and potential environmental toxicity remain concerns.103

Electronics

The increasing demand from consumers for bigger, brighter screens has led to a considerable increase in the employment of NPs for display technology in recent years. These kinds of sophisticated displays are frequently built into electronics like TVs and computer monitors. Modern devices like light-emitting diodes (LEDs), are made of materials such as zinc selenide, cadmium sulfide, nanocrystalline lead telluride, and other sulfides. The creation of quicker, smaller, and more energy-efficient devices has been made possible by nanoscale transistors and memory devices, which have completely changed the electronics industry.104 The consumer demand for lightweight, high-capacity batteries has been increasing for electronic devices such as mobile phones and laptops. The creation of fuel cells, batteries, and solar cells with higher efficiency is largely dependent on nanotechnology. Nanoparticles, including nanocrystalline nickel and metal hydrides, have been incorporated into aerogel to design the batteries in order to reduce charging frequency, store a large amount of energy, and increase durability throughout their usage period.105 Au and Ag nanoparticles have been incorporated to make OLED and LCD devices that improve the brightness, color, and contrast of image.106 NPs made of Zinc oxide are frequently used to increase charging speed and energy storage capacity in batteries and supercapacitors.107

Data Storage Systems

Nanoparticles are essential for boosting data storage capacity and advancing data storage technology due to their distinctive characteristics, including a large surface area and the capability to enable multi-dimensional encoding. They aid in the creation of smaller, faster, and more energy-efficient data storage solutions such as flash memory chips, USB drives, and SSDs.108 Hard drives and flash drives are two examples of data storage systems that can have their capacity and performance increased by nanoparticles.109 Magnetic NPs have shown great promise in data storage and retrieval via magnetism, they have been investigated for use in data storage devices like hard drives. One such example of magnetic NPs is iron oxide. The study has demonstrated their ability to store and recover data because of their magnetization and demagnetion properties.110

Future perspectives

Making precise-sized and shaped nanoparticles remains challenging. Various techniques have been employed to create the different nanoparticles, which can be difficult to create on a big industrial scale, under harsh chemical conditions and high temperatures. Besides this, the shape and size of NPs have a significant influence on their physical and chemical characteristics as well as their prospective uses. Thus, it becomes of utmost importance to synthesize and ensure small-size NPs enhance properties such as chemical reactivity, conductivity, thermal stability, high tensile strength, and wear resistance potential. Studies have reported that metal and metal oxide NPs have shown some adverse effects on the environment as well as human health, which is another big challenge that needs to be addressed. Few NPs, including AgNPs, TiO2, and ZnO have been demonstrated to harm aquatic life and have further effects on the ecosystem. Further studies regarding the detrimental impact of such NPs and their solutions to mitigate NPs-mediated toxic effects on the environment are matters of concern. NPs synthesis by biological methods is generally considered safer as compared to chemical synthesis due to the use of naturally derived, non-toxic agents and the absence of harsh chemical reactions.111 Biologically synthesized NPs are non-toxic, biocompatible, biodegradable, and widely used in biomedical applications to target various diseases via different mechanisms. Different classes of NPs possess great promise in targeted drug delivery systems, diagnostics imaging, tissue engineering, and gene delivery. Broad ranges of NPs have assisted treatment strategies of various diseases like infectious diseases, cancer, and brain-related diseases such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and Insomnia.112-114 Several studies mentioned that NPs formed by intracellular biological methods are most effective and showed outstanding results in the biomedical field, as they can be excreted through the kidney. However, finding a biological way to produce metal NPs with a small control size remains challenging. MNPs and MONPs are being utilized for energy conversion, storage, and environmental protection. Many different NPs have shown their potential to strengthen the efficiency of solar cells or enhance the performance and storage capacity of batteries. Also, they can be utilized in catalysis to increase the effectiveness of chemical reactions at a larger scale with the rectification of some issues.

Conclusion

Nanoparticles represent a revolutionary advancement in science and technology, offering unprecedented opportunities across multiple sectors including medicine, agriculture, energy, environmental remediation, food, cosmetics, electronics, and construction. This review highlighted the diverse classifications of NPs ranging from inorganic and organic types to carbon-based systems and explored their unique physicochemical properties that drive functional applications. NPs exhibit quantum confinement effects because they possess large surface area to volume which makes them capable of performing several actions in different fields. The unique multifaceted characteristics of NPs allow them to function in various fields, including drug delivery, theranostics, medicine, electronic devices, environmental remediation, cosmetics, etc. Despite the enormous potential and huge utilization of NPs in different sectors, several reported challenges related to toxicity, regulatory compliance, and large-scale production must be addressed in a proper way. As research continues to explore with the support of advanced tools like machine learning (ML), green synthesis, and bioengineering, the production of next-generation NPs could be more biocompatible and sustainable compared to the present one. A collaborative and interdisciplinary approach is the need of an hour for revealing the full promise of nanotechnology while ensuring safety and ethical responsibility in its global implementation.

Acknowledgement

Authors express sincere gratitude to the Interdisciplinary Nanotechnology Centre (INC), Z. H. College of Engineering and Technology, Aligarh Muslim University (AMU), Aligarh, and the Department of Biological Sciences, Indian Biological Sciences and Research Institute (IBRI), Noida, for their invaluable support and resources.

Funding Sources

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

This statement does not apply to this article.

Ethics Statement

This research did not involve human participants, animal subjects, or any material that requires ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not involve human participants, and therefore, informed consent was not required.

Clinical Trial Registration

This research does not involve any clinical trials.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

Not Applicable

Author Contributions

Hameim Yahya, Mudassir Alam: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing Original Draft.

Shahid Khan Alvi, Mohd Anas: Data Collection, Analysis.

Ameer Hamza, Alvia Farheen: Review & Editing.

Mudassir Alam: Visualization, Supervision, Project Administration

References

- Khan I, Saeed K, Khan I. Nanoparticles: Properties, applications and toxicities. Arabian Journal of Chemistry. 2019/11/01/ 2019;12(7):908-931. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2017.05.011

CrossRef - Bayda S, Adeel M, Tuccinardi T, Cordani M, Rizzolio F. The History of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology: From Chemical-Physical Applications to Nanomedicine. Molecules. Dec 27 2019;25(1)doi:10.3390/molecules25010112

CrossRef - Malik S, Muhammad K, Waheed Y. Nanotechnology: A Revolution in Modern Industry. Molecules. Jan 9 2023;28(2)doi:10.3390/molecules28020661

CrossRef - Hulla J, Sahu SC, Hayes AW. Nanotechnology: History and future. Human & experimental toxicology. 2015;34(12):1318-1321.

CrossRef - Roduner E. Size matters: why nanomaterials are different. Chemical society reviews. 2006;35(7):583-592.

CrossRef - Joudeh N, Linke D. Nanoparticle classification, physicochemical properties, characterization, and applications: a comprehensive review for biologists. Journal of Nanobiotechnology. 2022/06/07 2022;20(1):262. doi:10.1186/s12951-022-01477-8

CrossRef - Abbasi R, Shineh G, Mobaraki M, Doughty S, Tayebi L. Structural parameters of nanoparticles affecting their toxicity for biomedical applications: a review. J Nanopart Res. 2023;25(3):43. doi:10.1007/s11051-023-05690-w

CrossRef - Byakodi M, Shrikrishna NS, Sharma R, et al. Emerging 0D, 1D, 2D, and 3D nanostructures for efficient point-of-care biosensing. Biosensors and Bioelectronics: X. 2022/12/01/ 2022;12:100284. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosx.2022.100284

CrossRef - Kumari S, Sarkar L. A review on nanoparticles: Structure, classification, synthesis & applications. Journal of Scientific Research. 2021;65(8):42-46.

CrossRef - Alshammari BH, Lashin MM, Mahmood MA, et al. Organic and inorganic nanomaterials: fabrication, properties and applications. RSC advances. 2023;13(20):13735-13785.

CrossRef - Yan X, Sedykh A, Wang W, Yan B, Zhu H. Construction of a web-based nanomaterial database by big data curation and modeling friendly nanostructure annotations. Nature communications. 2020;11(1):2519.

CrossRef - Al-Thani AN, Jan AG, Abbas M, Geetha M, Sadasivuni KK. Nanoparticles in cancer theragnostic and drug delivery: A comprehensive review. Life Sciences. 2024/09/01/ 2024;352:122899. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2024.122899

CrossRef - Bano L, Rihan, Siddiqui Y, Alam M, Abbas K. Therapeutic potential of gold nanoparticles in cancer therapy: a comparative insight into synthesis overview and cellular mechanisms. Med Oncol. Jul 10 2025;42(8):320. doi:10.1007/s12032-025-02881-4

CrossRef - López-Valverde JA, Jiménez-Ortega E, Leal A. Clinical feasibility study of gold nanoparticles as theragnostic agents for precision radiotherapy. Biomedicines. 2022;10(5):1214.

CrossRef - Fu F, Dionysiou DD, Liu H. The use of zero-valent iron for groundwater remediation and wastewater treatment: A review. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2014/02/28/ 2014;267:194-205. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.12.062

CrossRef - Rashid AB, Haque M, Islam SMM, Uddin Labib KMR. Nanotechnology-enhanced fiber-reinforced polymer composites: Recent advancements on processing techniques and applications. Heliyon. 2024/01/30/ 2024;10(2):e24692. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e24692

CrossRef - Romero-Franco M, Godwin HA, Bilal M, Cohen Y. Needs and challenges for assessing the environmental impacts of engineered nanomaterials (ENMs). Beilstein Journal of Nanotechnology. // 2017;8:989-1014. doi:10.3762/bjnano.8.101

CrossRef - Sánchez-López E, Gomes D, Esteruelas G, et al. Metal-Based Nanoparticles as Antimicrobial Agents: An Overview. Nanomaterials (Basel). Feb 9 2020;10(2)doi:10.3390/nano10020292

CrossRef - Xu W, Yang T, Liu S, et al. Insights into the Synthesis, types and application of iron Nanoparticles: The overlooked significance of environmental effects. Environment International. 2022/01/01/ 2022;158:106980. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2021.106980

CrossRef - Altammar KA. A review on nanoparticles: characteristics, synthesis, applications, and challenges. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1155622. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2023.1155622

CrossRef - Yaqoob AA, Ahmad H, Parveen T, et al. Recent Advances in Metal Decorated Nanomaterials and Their Various Biological Applications: A Review. Front Chem. 2020;8:341. doi:10.3389/fchem.2020.00341

CrossRef - Vijayakumari J, Raj TLS, Selvi AA, Glenna R, Raja P. A comparative study of plant mediated synthesis of silver, copper and zinc nanoparticles from tiliacora acuminata (lam.) Hook. F. and their antibacterial activity studies. Synthesis. 2019;18:19-34.

- Bacha HB, Ullah N, Hamid A, Shah NA. A comprehensive review on nanofluids: Synthesis, cutting-edge applications, and future prospects. International Journal of Thermofluids. 2024/05/01/ 2024;22:100595. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijft.2024.100595

CrossRef - Yoon Y, Truong PL, Lee D, Ko SH. Metal-Oxide Nanomaterials Synthesis and Applications in Flexible and Wearable Sensors. ACS Nanoscience Au. 2022/04/20 2022;2(2):64-92. doi:10.1021/acsnanoscienceau.1c00029

CrossRef - Sofiah AGN, Samykano M, Pandey AK, Kadirgama K, Sharma K, Saidur R. Immense impact from small particles: Review on stability and thermophysical properties of nanofluids. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments. 2021/12/01/ 2021;48:101635. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seta.2021.101635

CrossRef - Pan J, Li C, Peng Y, et al. Application of transition metal (Ni, Co and Zn) oxides based electrode materials for ion-batteries and supercapacitors. International Journal of Electrochemical Science. 2023/09/01/ 2023;18(9):100233. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijoes.2023.100233

CrossRef - Aisida SO, Batool A, Khan FM, et al. Calcination induced PEG-Ni-ZnO nanorod composite and its biomedical applications. Materials Chemistry and Physics. 2020/11/15/ 2020;255:123603. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2020.123603

CrossRef - Gudkov SV, Serov DA, Astashev ME, Semenova AA, Lisitsyn AB. Ag(2)O Nanoparticles as a Candidate for Antimicrobial Compounds of the New Generation. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). Aug 5 2022;15(8)doi:10.3390/ph15080968

CrossRef - Li D, Chen S, Zhang K, et al. The interaction of Ag2O nanoparticles with Escherichia coli: inhibition–sterilization process. Scientific Reports. 2021/01/18 2021;11(1):1703. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-81305-5

CrossRef - Celebi D, Cinisli KT, Celebi O. NanoBio challenge: Investigation of antimicrobial effect by combining ZnO nanoparticles with plant extract Eleagnus angustifolia. Materials Today: Proceedings. 2021/01/01/ 2021;45:3814-3818. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2021.02.484

CrossRef - Azam A, Ahmed AS, Oves M, Khan MS, Habib SS, Memic A. Antimicrobial activity of metal oxide nanoparticles against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria: a comparative study. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7:6003-9. doi:10.2147/ijn.S35347

CrossRef - Carmo P, Garcia MT, Figueiredo-Godoi LMA, Lage ACP, Silva NSD, Junqueira JC. Metal Nanoparticles to Combat Candida albicans Infections: An Update. Microorganisms. Jan 5 2023;11(1)doi:10.3390/microorganisms11010138

CrossRef - Nguyen K-N, Sao L, Kyllo K, et al. Antibiofilm Activity of PDMS/TiO2 against Candida glabrata through Inhibited Hydrophobic Recovery. ACS Omega. 2024/10/15 2024;9(41):42593-42601. doi:10.1021/acsomega.4c07869

CrossRef - Sisakhtnezhad S, Rahimi M, Mohammadi S. Biomedical applications of MnO2 nanomaterials as nanozyme-based theranostics. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2023/07/01/ 2023;163:114833. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114833

CrossRef - Ahamed M, Alhadlaq HA, Khan MM, Karuppiah P, Al-Dhabi NA. Synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of copper oxide nanoparticles. Journal of Nanomaterials. 2014;2014(1):637858.

CrossRef - Tasnim NT, Ferdous N, Rumon MMH, Shakil MS. The Promise of Metal-Doped Iron Oxide Nanoparticles as Antimicrobial Agent. ACS Omega. 2024/01/09 2024;9(1):16-32. doi:10.1021/acsomega.3c06323

CrossRef - Saba I, Batoo KM, Wani K, Verma R, Hameed S. Exploration of Metal-Doped Iron Oxide Nanoparticles as an Antimicrobial Agent: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus. Sep 2024;16(9):e69556. doi:10.7759/cureus.69556

CrossRef - Fateh ST, Aghaii AH, Aminzade Z, et al. Inorganic nanoparticle-cored dendrimers for biomedical applications: A review. Heliyon. 2024/05/15/ 2024;10(9):e29726. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e29726

CrossRef - Guo B-L, Han P, Guo L-C, et al. The Antibacterial Activity of Ta-doped ZnO Nanoparticles. Nanoscale Research Letters. 2015/08/21 2015;10(1):336. doi:10.1186/s11671-015-1047-4

CrossRef - Dhanasekar M, Jenefer V, Nambiar RB, et al. Ambient light antimicrobial activity of reduced graphene oxide supported metal doped TiO2 nanoparticles and their PVA based polymer nanocomposite films. Materials Research Bulletin. 2018/01/01/ 2018;97:238-243. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.materresbull.2017.08.056

CrossRef - Roy M, Roy A, Rustagi S, Pandey N. An Overview of Nanomaterial Applications in Pharmacology. Biomed Res Int. 2023;2023:4838043. doi:10.1155/2023/4838043

CrossRef - Esakkimuthu T, Sivakumar D, Akila S. Application of nanoparticles in wastewater treatment. Pollut Res. 2014;33(03):567-571.

- Vatankhah A, Oroojalian F, Moghaddam SH, Kesharwani P, Sahebkar A. State-of-the-Art Review on Liposomes as Versatile Cancer Vaccine Delivery Systems. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology. 2025/04/25/ 2025:106975. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jddst.2025.106975

CrossRef - Lee Y, Thompson DH. Stimuli-responsive liposomes for drug delivery. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. Sep 2017;9(5)doi:10.1002/wnan.1450

CrossRef - Sonju JJ, Dahal A, Singh SS, et al. A pH-sensitive liposome formulation of a peptidomimetic-Dox conjugate for targeting HER2 + cancer. Int J Pharm. Jan 25 2022;612:121364. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm. 2021.121364

CrossRef - Ahmad MZ, Mustafa G, Abdel-Wahab BA, et al. From bench to bedside: Advancing liposomal doxorubicin for targeted cancer therapy. Results in Surfaces and Interfaces. 2025/05/01/ 2025;19:100473. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rsurfi.2025.100473

CrossRef - Cunha J, Latocheski E, Fidalgo ACD, Gerola AP, Marin CFdF, Ribeiro AJ. Core-shell hybrid liposomes: Transforming imaging diagnostics and therapeutic strategies. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. 2025/07/01/ 2025;251:114597. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2025.114597

CrossRef - Gregoriadis G. Liposomes and mRNA: Two technologies together create a COVID-19 vaccine. Medicine in Drug Discovery. 2021/12/01/ 2021;12:100104. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.medidd.2021.100104

CrossRef - Ghosh B, Biswas S. Polymeric micelles in cancer therapy: State of the art. Journal of Controlled Release. 2021/04/10/ 2021;332:127-147. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.02.016

CrossRef - Mi P. Stimuli-responsive nanocarriers for drug delivery, tumor imaging, therapy and theranostics. Theranostics. 2020;10(10):4557-4588. doi:10.7150/thno.38069

CrossRef - Imtiaz S, Ferdous UT, Nizela A, et al. Mechanistic study of cancer drug delivery: Current techniques, limitations, and future prospects. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2025/06/05/ 2025;290:117535. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2025.117535

CrossRef - Ghezzi M, Pescina S, Padula C, et al. Polymeric micelles in drug delivery: An insight of the techniques for their characterization and assessment in biorelevant conditions. Journal of Controlled Release. 2021/04/10/ 2021;332:312-336. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.02.031

CrossRef - Mustafa M, Abbas K, Alam M, et al. Molecular pathways and therapeutic targets linked to triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). Mol Cell Biochem. Apr 2024;479(4):895-913. doi:10.1007/s11010-023-04772-6

CrossRef - Wei X, Song M, Li W, Huang J, Yang G, Wang Y. Multifunctional nanoplatforms co-delivering combinatorial dual-drug for eliminating cancer multidrug resistance. Theranostics. 2021;11(13):6334-6354. doi:10.7150/thno.59342

CrossRef - Díez-Pascual AM. Carbon-Based Nanomaterials. Int J Mol Sci. Jul 20 2021;22(14)doi:10.3390/ ijms22147726

CrossRef - Datta D, Das KP, Deepak KS, Das B. Chapter 3 – Candidates of functionalized nanomaterial-based membranes. In: Dutta S, Hussain CM, eds. Membranes with Functionalized Nanomaterials. Elsevier; 2022:81-127.

CrossRef - Khan Y, Sadia H, Ali Shah SZ, et al. Classification, Synthetic, and Characterization Approaches to Nanoparticles, and Their Applications in Various Fields of Nanotechnology: A Review. Catalysts. 2022;12(11):1386.

CrossRef - Yudoh K, Shishido K, Murayama H, et al. Water-soluble C60 fullerene prevents degeneration of articular cartilage in osteoarthritis via down-regulation of chondrocyte catabolic activity and inhibition of cartilage degeneration during disease development. Arthritis Rheum. Oct 2007;56(10):3307-18. doi:10.1002/art.22917

CrossRef - Alam M. and Kashif Abbas. Rethinking Rheumatoid Arthritis Management: Is Personalized Medicine the Future?. Arch Rheum & Arthritis Res. 3 (3): 2025. ARAR. MS. ID. 000564.

- Olabi AG, Abdelkareem MA, Wilberforce T, Sayed ET. Application of graphene in energy storage device – A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 2021/01/01/ 2021;135:110026. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2020.110026

CrossRef - Govindaraj P, Sokolova A, Salim N, et al. Distribution states of graphene in polymer nanocomposites: A review. Composites Part B: Engineering. 2021/12/01/ 2021;226:109353. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2021.109353

CrossRef - Banerjee P, Das P, Zaman A, Das P. Application of graphene oxide nanoplatelets for adsorption of Ibuprofen from aqueous solutions: Evaluation of process kinetics and thermodynamics. Process Safety and Environmental Protection. 2016/05/01/ 2016;101:45-53. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2016.01.021

CrossRef - Baratta M, Tursi A, Curcio M, et al. Removal of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs from Drinking Water Sources by GO-SWCNT Buckypapers. Molecules. 2022;27(22):7674.

CrossRef - Ahmad J, Zhou Z. Properties of concrete with addition carbon nanotubes: A review. Construction and Building Materials. 2023/08/22/ 2023;393:132066. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.conbuildmat.2023.132066

CrossRef - Yu W, Zhou H, Li BQ, Ding S. 3D printing of carbon nanotubes-based microsupercapacitors. ACS applied materials & interfaces. 2017;9(5):4597-4604.

CrossRef - Ye W, Wu W, Hu X, et al. 3D printing of carbon nanotubes reinforced thermoplastic polyimide composites with controllable mechanical and electrical performance. Composites Science and Technology. 2019;182:107671.

CrossRef - Feng L, Xie N, Zhong J. Carbon Nanofibers and Their Composites: A Review of Synthesizing, Properties and Applications. Materials (Basel). May 15 2014;7(5):3919-3945. doi:10.3390/ma7053919

CrossRef - Alegre C, Modica E, Di Blasi A, et al. NiCo-loaded carbon nanofibers obtained by electrospinning: Bifunctional behavior as air electrodes. Renewable Energy. 2018/09/01/ 2018;125:250-259. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2018.02.089

CrossRef - Zhang L, Aboagye A, Kelkar A, Lai C, Fong H. A review: carbon nanofibers from electrospun polyacrylonitrile and their applications. Journal of Materials Science. 2014/01/01 2014;49(2):463-480. doi:10.1007/s10853-013-7705-y

CrossRef - Feng L, Xie N, Zhong J. Carbon Nanofibers and Their Composites: A Review of Synthesizing, Properties and Applications. Materials. 2014;7(5):3919-3945.

CrossRef - Zhang B, Kang F, Tarascon J-M, Kim J-K. Recent advances in electrospun carbon nanofibers and their application in electrochemical energy storage. Progress in Materials Science. 2016/03/01/ 2016;76:319-380. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmatsci.2015.08.002

CrossRef - Afzal O, Altamimi ASA, Nadeem MS, et al. Nanoparticles in Drug Delivery: From History to Therapeutic Applications. Nanomaterials (Basel). Dec 19 2022;12(24)doi:10.3390/nano12244494

CrossRef - Sun L, Liu H, Ye Y, et al. Smart nanoparticles for cancer therapy. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 2023/11/03 2023;8(1):418. doi:10.1038/s41392-023-01642-x

CrossRef - Moazzam M, Zhang M, Hussain A, Yu X, Huang J, Huang Y. The landscape of nanoparticle-based siRNA delivery and therapeutic development. Molecular Therapy. 2024/02/07/ 2024;32(2):284-312. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2024.01.005

CrossRef - Gade L, Boyd BJ, Malmsten M, Heinz A. Stimuli-responsive drug delivery systems for inflammatory skin conditions. Acta Biomaterialia. 2024/10/01/ 2024;187:1-19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j. actbio.2024.08.037

CrossRef - Sakore P, Bhattacharya S, Belemkar S, Prajapati BG, Elossaily GM. The theranostic potential of green nanotechnology-enabled gold nanoparticles in cancer: A paradigm shift on diagnosis and treatment approaches. Results in Chemistry. 2024/01/01/ 2024;7:101264. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rechem. 2023.101264

CrossRef - Kim KT, Lee JY, Kim DD, Yoon IS, Cho HJ. Recent Progress in the Development of Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)-Based Nanostructures for Cancer Imaging and Therapy. Pharmaceutics. Jun 14 2019;11(6)doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics11060280

CrossRef - Andrejeva G, Rathmell JC. Similarities and Distinctions of Cancer and Immune Metabolism in Inflammation and Tumors. Cell Metab. Jul 5 2017;26(1):49-70. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2017.06.004

CrossRef - Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. May 2021;71(3):209-249. doi:10.3322/caac.21660

CrossRef - Li SR, Huo FY, Wang HQ, et al. Recent advances in porous nanomaterials-based drug delivery systems for cancer immunotherapy. J Nanobiotechnology. Jun 14 2022;20(1):277.doi:10.1186/s 12951-022-01489-4

CrossRef - Rao L, Yu GT, Meng QF, et al. Cancer cell membrane‐coated nanoparticles for personalized therapy in patient‐derived xenograft models. Advanced Functional Materials. 2019;29(51):1905671.

CrossRef - Wang Y, Luan Z, Zhao C, Bai C, Yang K. Target delivery selective CSF-1R inhibitor to tumor-associated macrophages via erythrocyte-cancer cell hybrid membrane camouflaged pH-responsive copolymer micelle for cancer immunotherapy. Eur J Pharm Sci. Jan 15 2020;142:105136. doi:10.1016/j.ejps.2019.105136

CrossRef - Kaczmarek JC, Kauffman KJ, Fenton OS, et al. Optimization of a Degradable Polymer-Lipid Nanoparticle for Potent Systemic Delivery of mRNA to the Lung Endothelium and Immune Cells. Nano Lett. Oct 10 2018;18(10):6449-6454. doi:10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b02917

CrossRef - Singh T, Shukla S, Kumar P, Wahla V, Bajpai VK, Rather IA. Application of nanotechnology in food science: perception and overview. Frontiers in microbiology. 2017;8:1501.

CrossRef - Anvar AA, Ahari H, Ataee M. Antimicrobial properties of food nanopackaging: A new focus on foodborne pathogens. Frontiers in microbiology. 2021;12:690706.

CrossRef - Firmanda A, Fahma F, Warsiki E, et al. Antimicrobial mechanism of nanocellulose composite packaging incorporated with essential oils. Food Control. 2023/05/01/ 2023;147:109617. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2023.109617

CrossRef - Hakeem MJ, Feng J, Nilghaz A, et al. Active Packaging of Immobilized Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Controls Campylobacter jejuni in Raw Chicken Meat. Appl Environ Microbiol. Oct 28 2020;86(22)doi:10.1128/aem.01195-20

CrossRef - Soltan Dallal MM, Karimaei S, Hajighasem M, et al. Evaluation of zinc oxide nanocomposite with Aloe vera gel for packaging of chicken fillet against Salmonella typhi and Salmonella para typhi A. Food Sci Nutr. Oct 2023;11(10):5882-5889. doi:10.1002/fsn3.3528

CrossRef - Abbas K, Alam M, Kamal S. Heavy metals contamination in water bodies and its impact on fish health and fish nutritional value: A. International Journal of Fauna and Biological Studies. 2021;8:43-49.

CrossRef - Khan P, Ali S, Jan R, Kim K-M. Lignin Nanoparticles: Transforming Environmental Remediation. Nanomaterials. 2024;14(18):1541.

CrossRef - More PR, Pandit S, Filippis A, Franci G, Mijakovic I, Galdiero M. Silver Nanoparticles: Bactericidal and Mechanistic Approach against Drug Resistant Pathogens. Microorganisms. Feb 1 2023;11(2)doi:10.3390/microorganisms11020369

CrossRef - Sundaram T, Rajendran S, Natarajan S, Vinayagam S, Rajamohan R, Lackner M. Environmental fate and transformation of TiO₂ nanoparticles: A comprehensive assessment. Alexandria Engineering Journal. 2025/03/01/ 2025;115:264-276. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2024.12.054

CrossRef - Kholief MG, Hesham AE-L, Hashem FS, Mohamed FM. Synthesis and utilization of titanium dioxide nano particle (TiO2NPs) for photocatalytic degradation of organics. Scientific Reports. 2024/05/17 2024;14(1):11327. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-53617-9

CrossRef - Ghosh S, Polaki S, Macrelli A, Casari CS, Barg S, Jeong SM. Nanoparticle-enhanced Multifunctional Nanocarbons as Metal-ion Battery and Capacitor Anodes and Supercapacitor Electrodes–Review. arXiv preprint arXiv:220112463. 2022;

- Çelebi M, Çanakçı A, Güler O, Karabacak H, Akgül B, Özkaya S. A study on the improvement of wear and corrosion properties of ZA40/Graphene/B4C hybrid nanocomposites. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 2023/12/05/ 2023;966:171628. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2023.171628

CrossRef - Macías-Silva MA, Cedeño-Muñoz JS, Morales-Paredes CA, et al. Nanomaterials in construction industry: An overview of their properties and contributions in building house. Case Studies in Chemical and Environmental Engineering. 2024/12/01/ 2024;10:100863. doi:https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j. cscee.2024.100863

CrossRef - Li C, Cao Y, Li G, et al. Modified cementitious materials incorporating Al2O3 and SiO2 nanoparticle reinforcements: An experimental investigation. Case Studies in Construction Materials. 2023/12/01/ 2023;19:e02542. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2023.e02542

CrossRef - Najafi Kani E, Rafiean AH, Alishah A, Hojjati Astani S, Ghaffar SH. The effects of Nano-Fe2O3 on the mechanical, physical and microstructure of cementitious composites. Construction and Building Materials. 2021/01/10/ 2021;266:121137. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121137

CrossRef - Khannyra S, Mosquera MJ, Addou M, Gil MLA. Cu-TiO2/SiO2 photocatalysts for concrete-based building materials: Self-cleaning and air de-pollution performance. Construction and Building Materials. 2021/12/27/ 2021;313:125419. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.125419

CrossRef - Haw TT, Hart F, Rashidi A, Pasbakhsh P. Sustainable cementitious composites reinforced with metakaolin and halloysite nanotubes for construction and building applications. Applied Clay Science. 2020/04/01/ 2020;188:105533. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2020.105533

CrossRef - Smijs TG, Pavel S. Titanium dioxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles in sunscreens: focus on their safety and effectiveness. Nanotechnol Sci Appl. Oct 13 2011;4:95-112. doi:10.2147/nsa.S19419

CrossRef - Vaudagna MV, Aiassa V, Marcotti A, et al. Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles in sunscreens and skin photo-damage. Development, synthesis and characterization of a novel biocompatible alternative based on their in vitro and in vivo study. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology. 2023/06/01/ 2023;15:100173. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpap.2023.100173

CrossRef - Babarus I, Lungu I-I, Stefanache A. The dynamic duo: titanium dioxide and zinc oxide in uv-protective cosmetic. 2023;

- Payal, Pandey P. Role of Nanotechnology in Electronics: A Review of Recent Developments and Patents. Recent Pat Nanotechnol. 2022;16(1):45-66. doi:10.2174/1872210515666210120114504

CrossRef - Allsopp M, Walters A, Santillo D. Nanotechnologies and nanomaterials in electrical and electronic goods: A review of uses and health concerns. Greenpeace Research Laboratories, London. 2007;

- Kang K, Byeon I, Kim YG, Choi Jr, Kim D. Nanostructures in Organic Light‐Emitting Diodes: Principles and Recent Advances in the Light Extraction Strategy. Laser & Photonics Reviews. 2024;18(8): 2400547.

CrossRef - Kumar RD, Nagarani S, Balachandran S, et al. High performing hexagonal-shaped ZnO nanopowder for Pseudo-supercapacitors applications. Surfaces and Interfaces. 2022/10/01/ 2022;33:102203. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfin.2022.102203

CrossRef - Sarid D, McCarthy B, Jabbour GE. Nanotechnology for Data Storage Applications. In: Bhushan B, ed. Springer Handbook of Nanotechnology. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2004:899-920.

CrossRef - Taha TB, Barzinjy AA, Hussain FHS, Nurtayeva T. Nanotechnology and Computer Science: Trends and advances. Memories – Materials, Devices, Circuits and Systems. 2022/10/01/ 2022;2:100011. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memori.2022.100011

CrossRef - Powell CD, Atkinson AJ, Ma Y, et al. Magnetic nanoparticle recovery device (MagNERD) enables application of iron oxide nanoparticles for water treatment. Journal of Nanoparticle Research. 2020/02/12 2020;22(2):48. doi:10.1007/s11051-020-4770-4

CrossRef - Yadav P, Azram M, Faraz M, et al. In Silico Screening of Rauwolfia Serpentina Phytochemicals as Orexin Receptor-2 Agonists for the Management of Narcolepsy. International Journal of Biochemistry Research & Review. 02/03 2025;34(1):76-102. doi:10.9734/ijbcrr/2025/v34i1951

CrossRef - Abbas K, Alam M, Ansari MS, et al. Isorauhimbine and Vinburnine as Novel 5-HT2A Receptor Antagonists From Rauwolfia serpentina for the Treatment of Insomnia: An In Silico Investigation. Chronobiol Med. 12 2024;6(4):169-182. doi:10.33069/cim.2024.0023

CrossRef - Alam M, Abbas K, Mustafa M, Usmani N, Habib S. Microbiome-based therapies for Parkinson’s disease. Front Nutr. 2024;11:1496616. doi:10.3389/fnut.2024.1496616

CrossRef - Abbas K, Alam M, Ali V, Ajaz M. Virtual screening, molecular docking and ADME/T properties analysis of neuroprotective property present in root extract of chinese skullcap against β-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1) in case of alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry. 2023;12(1):146-153.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.