Manuscript accepted on : 25-07-2025

Published online on: 10-09-2025

Plagiarism Check: Yes

Reviewed by: Dr. Makhabbah Jamilatun

Second Review by: Dr. Sura Maan Salim

Final Approval by: Dr. Eugene A. Silow

Evaluation of Antioxidant Capacity and Safety Profile of Selected Medicinal Plant Extracts.

Falak Bamne1 , Pawan Sharma1

, Pawan Sharma1 , Nikhat Shaikh2

, Nikhat Shaikh2 , Munira Momin3

, Munira Momin3 , Tabassum Khan4

, Tabassum Khan4 and Ahmad Ali1*

and Ahmad Ali1*

1Department of Life Sciences, University of Mumbai, Vidyanagari, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

2Regional Research Institute of Unani Medicine, Kharghar, New Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

3Department of Pharmaceutics, SVKM’s Dr. Bhanuben Nanavati College of Pharmacy, Vile Parle(W), Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

4Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, SVKM’s Dr. Bhanuben Nanavati College of Pharmacy, Vile Parle(W), Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

Corresponding Author E-mail:ahmadali@mu.ac.in

ABSTRACT: Medicinal plants are widely recognised for their medicinal benefits, notably due to their bioactive phytochemicals and antioxidant capacity. The aim of the study is to investigate the phytochemical composition, antioxidant activity and cytotoxic effect of medicinal plants Ferula asafoetida Linn., Hyoscyamus niger Linn, Matricaria chamomilla Linn, Styrax benzoin Dryland., and Sesamum indicum Linn. Hydroalcoholic extracts of the medicinal plants were extracted using Soxhlet apparatus. Phytochemical screening was performed to identify the secondary metabolites. Quantitative analysis of protein, carbohydrates, total phenolic content (TPC) and flavonoids content (TFC). Antioxidant activity was evaluated using 2,2'-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) assay, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay, the nitric oxide (NO) scavenging assay, Lipid peroxidation assay, ferric reducing antioxidant power assay and DNA damage protection against the oxidative stress induced by hydrogen peroxide. The toxicity evaluation is measured by the HET-CAM (Hen’s Egg Test – Chorioallantoic Membrane) assay. The functional group detection is done by the FTIR (Fourier Transform Infrared) spectroscopy for better exposure to the identification of bioactive compounds. The results show that the phytochemical content of these plant extracts is dose dependent as the concentration of these extracts increases the phytochemical increase and eventually the antioxidant activity also increases. This notable behavior of these extracts aligns with the published data and suggests the efficiency of these plants in terms of therapeutics and health care.

KEYWORDS: Antioxidants; DNA damage; FTIR; Herbal medicine; HET-CAM; Phytochemicals

| Copy the following to cite this article: Bamne F, Sharma P, Shaikh N, Momin M, Khan T, Ali A. Evaluation of Antioxidant Capacity and Safety Profile of Selected Medicinal Plant Extracts. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(3). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Bamne F, Sharma P, Shaikh N, Momin M, Khan T, Ali A. Evaluation of Antioxidant Capacity and Safety Profile of Selected Medicinal Plant Extracts. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(3). Available from: https://bit.ly/47DzuGk |

Introduction

The herbal plants were always known for its sources of some bioactive and derivative compounds that are essential for the antioxidant and eventually prevention of oxidative stress caused complications.1 Among those plants, Ferula asafoetida resin, Matricaria chamomilla whole plant, Sesamum indicum seeds, Styrax benzoin resin, and Hyoscyamus niger seeds show maximum efficacy to the diseases. These plants are rich in different phytochemicals that target different metabolic and catabolic reactions, eventually balancing the reaction by neutralizing the by-products and some free radicals that are formed during the reaction. Traditionally these plants were used in different cultures for treating various health issues such as their ability to treat gastrointestinal complication, anti-inflammatory, sedative and to treat cold and flu. It is consumed as condiments, herbal tea and as oil. F. asafoetida, is well known for its ability to reduce the inflammation, diabetes and oxidative stress.2,3 H. niger have unique photochemical systems that are essential for neutralizing the free radicals such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reduces oxidative stress.4 M. chamomilla is known for its aroma used for calming, eventually by reducing the oxidative free radicals due to the presence of some unique flavonoids and steroids.5 S. indicum and S. benzoin are enriched with terpenoids and phenolic compounds that are essential for antioxidant activity that promotes DNA repair and prevent DNA damage caused by oxidative stress and maintain the genomic stability.6,7

At the molecular level, these plants exhibit DNA repair phenomenon such as base excision repair and nucleotide excision repair, which is caused by oxidative stress to DNA. It improves and inhibits the immunological responses to the inflammation caused by the oxidate stress. Untreated, ignorance of having an unhealthy lifestyle can cause metabolic and catabolic imbalance caused by free radicals that increases oxidative stress, eventually triggers cell apoptosis precursors and also can lead to DNA mutation which can cause oncological disorder.8 Hence to evaluate the toxicity effect of these medicinal plant Hen’s Egg Test on Chorioallantoic Membrane (HET-CAM) assay is performed. The results estimate that the plant extracts were classified as non-irritant.

These findings suggest the plants exhibit favorable safety potential that enhance the potential for use in medicinal practices. The antioxidant and DNA repair potential of F. asafoetida, H. niger, M. chamomilla, S. indicum, and S. benzoin highlights their significance in protecting cellular integrity, offering the pathway to plant based therapeutic approaches.

Material and Methods

Sample preparation and authentication

The extraction of plant samples was performed using Soxhlet extraction. In this process, 5 grams of powdered plant material were continuously extracted with a mixture of distilled water and methanol in a 7:3 v/v ratio. The extracts were then filtered and evaporated to dryness.9 The plant materials were obtained from certified herbal medicine suppliers and verified by Dr. Rashid from Ajmal Khan Tibbia College, Aligarh Muslim University. Their taxonomic identification was officially verified with Certificate No. 843/DS.

Qualitative analysis for phytochemicals

Phytochemical detection involves various qualitative methods: carbohydrates are identified by Molisch’s and Benedict’s tests, amino acids by Ninhydrin, proteins by Biuret and Xanthoproteic tests, steroids by Salkowski and Liebermann-Burchard tests, glycosides by Borntrager’s tests, flavonoids by Shinoda tests, phenols by lead acetate tests, tannins by Gelatin tests; terpenoids by Salkowski test; and alkaloids by Dragendorff’s and Mayer’s tests. These methods offer reliable preliminary screening for phytochemical analysis.9,10

Quantitative analysis

Determination of Carbohydrate content

The carbohydrate content was estimated by using the 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid (DNSA) method, added 1ml of the plant extracts to 1ml of DNSA reagent. The reaction mixture is treated in boiling water bath for 300 seconds. Add 3ml of distilled water and optical density (OD) was measured at 525 nm.11

Quantification of Protein content

The hydroalcoholic extracts samples were mixed with Bradford reagent, which contains Coomassie Blue G-250 dye. Upon binding to protein, the dye undergoes a shift in optical density (OD), brown to blue color change is observed. The OD is recorded at 595 nm using a spectrophotometer. The protein concentration in the samples was then calculated based on the standard curve obtained from the BSA measurements.12

Determination of phenolic content (TPC)

The phenolic content of the hydroalcoholic plants extracts was evaluated using the Folin-Ciocalteu (FC) method. Gallic acid is used as standard.13 The extracts (1 mg/mL) was combined with 10% FC reagent (v/v). After a 5-minute incubation, 7.5% sodium carbonate (w/v) was added and allowed to react for 45 minutes at 37°C. The optical density (OD) was recorded at 765 nm using spectrophotometer against a blank. The results were represented as mg gallic acid equivalent per gram plants dry weight (mg GAE/g DW).14

Total flavonoid content (TFC)

The total flavonoid content of the plant extracts was assessed using the aluminum chloride colorimetric method with quercetin as the standard calibration curve.15 The extracts (1 mg/mL) was mixed 10% aluminum chloride, 1 M potassium acetate, and of distilled water. After 30 minutes of incubation at 37°C, the optical density (OD) was recorded at 415 nm using a spectrophotometer against a blank. The results were represented as mg quercetin equivalent per gram of plants dry weight (mg QE/g DW).14

Evaluation of antioxidant activity of extracts.

Free radical scavenging assays

To evaluate the extract’s total antioxidant and free radical scavenging capacity, numerous assays are used, each based on a distinct mechanism.16 The DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) assay determines if the extract can donate hydrogen atoms or transfer electrons to neutralise DPPH radicals.17 This technique produces a colour change from violet to yellow, which is measured at 517 nm with ascorbic acid as a calibration standard.18 The ABTS (2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)) assay measures the scavenging activity of hydrophilic and lipophilic substances by lowering the ABTS•⁺ radical cation.19 For this experiment, the extract (concentrations ranging from 20 mg/ml to 100 mg/ml) is mixed with a pre-prepared ABTS solution, incubated for 30 minutes, and measured at 734 nm. A calibration curve is created using gallic acid.16 The Nitric oxide (NO) scavenging assay evaluates the extract’s capacity to neutralise nitric oxide radicals by preventing nitrite production 20. This approach involves mixing the extract with freshly made Griess reagent, incubating it for two hours, and analysing it at 540 nm.16 Each of these assays assesses the extract’s antioxidant potential using spectrophotometric monitoring of colour changes.

Where Ao is the absorption of control and As is the absorption of the tested extract solution.

Reducing antioxidant power assay (FRAP assay)

The Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) assay measures antioxidant activity by reducing ferric ions (Fe³⁺) to ferrous ions (Fe²⁺), resulting in a colour shift at 593 nm. In this test, 3 mL of FRAP reagent was mixed with 1 mL of plant extract (20-100 mg/mL) and incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes in the dark. The optical density (OD) was measured at 593 nm using Trolox as the standard, and samples were analysed in triplicate. The blank included all reagents except the sample.21

Lipid peroxidation assay

The lipid peroxidation (LPO) experiment involved combining 1 mL of plant extract with 1 mL of thiobarbituric acid (TBA). The mixture was then placed in a boiling water bath at 95°C for 60 minutes. After the test tubes had cooled to room temperature, the optical density (OD) was measured at 532 nm. To test linearity and MDA level in the plant extract, a standard calibration curve was created using malondialdehyde (MDA).22

Investigation of H2O2-Mediated DNA Damage Using DNA Nicking Assay

The DNA nicking assay evaluates the ability of substances to prevent or cause oxidative DNA damage by monitoring structural changes in plasmid DNA. In this study, pBR322 plasmid DNA (0.25 µg) was exposed to 60 mM H2O2 in 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37°C to induce damage. Hydroalcoholic extracts were tested for their protective effect across different conditions: DNA alone, DNA with H2O2, DNA with the extract, and DNA with both the extract and H2O2. Following incubation, the samples were analyzed using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, and DNA bands were visualized with a Gel-Doc system to assess nicking and protection.21

Irritation and toxicity assay: HET-CAM (Hen’s Egg Test – Chorioallantoic Membrane) assay

Fertilised hen eggs were procured from the Central Poultry Development Organisation (Western Region), Aarey Milk Colony, Mumbai. They were incubated for 10 days at 37.8 ± 1.0°C and 45-65% humidity. On day ten, the eggs were candled to determine embryo viability, and any faulty eggs were eliminated. The shell of the air cell was removed, and the inner membrane was peeled back to reveal the vascularised Chorioallantoic membrane (CAM). A 0.2 mL sample of each test drug (n = 3) was placed on the CAM and left for 300 seconds. The test groups contained 0.1 M NaOH (positive control for haemorrhage and coagulation), 1% sodium lauryl sulphate (positive control for vasoconstriction), 0.9% NaCl (negative control), and hydroalcoholic extracts of E. globulus, S. indicum, M. chamomilla, and F. asafoetida, H. niger, S. benzoin. After 20 seconds, the CAM was rinsed with saline to observe vascular effects. The irritation index (RI) was calculated using the appropriate equation:

where H = hemorrhage, C = coagulation, L = vascular lysis, RI = irritation index, and s = start second.23

Based on their RI, the tested substances were categorized into three groups.

| Sr.no | Irritation category | Irritation index |

| 1. | Non-irritating | 0-0.9 |

| 2. | Irritating | 1-8.9 |

| 3. | Severe irritating | 9-21 |

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy studies

The investigation was carried out utilising a Shimadzu FTIR spectrometer and the LabSolutions IR program. A little drop of hydroalcoholic plant extract was put to a dry NaCl window to produce a thin layer. The sample is subsequently placed into the sample holder, and the spectra are measured in the infrared band 4000-400 cm-1. The FTIR spectral peaks of plant extracts were analysed to discover functional groups linked with the bioactive substances contained in the phytochemicals of plant extracts.

Results

Extraction yields of hydroalcoholic extracts varied among the studied plants as shown in table 2. F. asafoetida showed the highest yield at 46.33%, while S. benzoin exhibited the lowest yield at 19.77%. S. indicum, M. chamomilla, and H. niger demonstrated moderate to low yields, with 35%, 27%, and 20.77%, respectively

Qualitative analysis for phytochemical analysis

The phytochemical screening of the hydroalcoholic extracts revealed distinct compositions among the studied plants. Carbohydrates, flavonoids, and phenols were consistently present in all extracts as shown in table 1, while tannins were absent across the board. Amino acids and proteins were detected in H. niger, M. chamomilla, S. indicum, and S. benzoin, but not in F. asafoetida. Steroids were identified exclusively in M. chamomilla, while glycosides were detected solely in F. asafoetida. Terpenoids were found in F. asafoetida, H. niger, and M. chamomilla, and alkaloids were present in M. chamomilla and S. indicum.

Table 1: Phytochemical screening of Hydroalcoholic Extract.

| Sr. No. | Phytochemical | F. asafoetida | H. niger | M. chamomilla | S. indicum | S. benzoin |

| 1. | Amino acids & Proteins | – | + | + | + | + |

| 2. | Carbohydrates | + | + | + | + | + |

| 3. | Steroids | – | – | + | – | – |

| 4. | Flavonoids | + | + | + | + | + |

| 5. | Glycosides | + | – | – | – | – |

| 6. | Tannins | – | – | – | – | – |

| 7. | Phenols | + | + | + | + | + |

| 8. | Alkaloids | – | – | + | + | – |

| 9. | Terpenoids | + | + | + | – | – |

Quantitative analysis

Total carbohydrate and protein content

Total carbohydrate content in the plant extracts varied significantly as shown in table 2. F. asafoetida exhibited the highest carbohydrate content at 0.45 mg/mL, followed by M. chamomilla with 0.42 mg/mL. H. niger showed a moderate carbohydrate content of 0.27 mg/mL, while S. indicum and S. benzoin had the lowest levels, both measuring 0.14 mg/mL. The protein content of the plant extracts showed considerable variation as shown in table 2. M. chamomilla exhibited the highest protein content at 0.97 mg/mL, while S. benzoin had the lowest at 0.14 mg/mL. Moderate protein levels were observed in S. indicum (0.30 mg/mL), H. niger (0.20 mg/mL), and F. asafoetida (0.15 mg/mL).

Total phenolic and flavonoid content

The phenolic content of the plant extracts showed significant variation as shown in table 2. M. chamomilla exhibited the highest phenolic content at 6.26 ± 0.11 GAE/g, while F. asafoetida had the lowest at 0.29 ± 0.02 GAE/g. H. niger and S. indicum demonstrated moderate phenolic levels, measuring 2.93 ± 0.16 GAE/g and 1.13 ± 0.06 GAE/g, respectively. S. benzoin displayed a slightly lower phenolic content of 1.02 ± 0.05 GAE/g. The flavonoid content of the plant extracts varied across different species as shown in table 2, reflecting differences in their potential antioxidant activity. S. indicum exhibited the highest flavonoid content at 0.59 ± 0.02 QE/mg, followed closely by H. niger with 0.56 ± 0.02 QE/mg. F. asafoetida and S. benzoin showed moderate levels of flavonoids, measuring 0.46 ± 0.03 QE/mg and 0.41 ± 0.01 QE/mg, respectively. In contrast, M. chamomilla had the lowest flavonoid content at 0.35 ± 0.04 QE/mg.

Table 2: Extractive Yield, Phytochemical, Carbohydrate, and Protein Content of Medicinal Plants

| Sr. No. | Plant Name | Extractive Yield (%) ± SD | Total Carbohydrate Content ± SD (mg/ml) | Protein Content ± SD (mg/ml) | Phenolic Content ± SD (GAE/g) | Flavonoid Content ± SD (QE/mg) |

| 1 | F. asafoetida | 46.33 ± 0.34 | 0.45 ± 0.01 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.29 ± 0.02 | 0.46 ± 0.03 |

| 2 | H. niger | 20.77 ± 0.08 | 0.27 ± 0.01 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 2.93 ± 0.16 | 0.56 ± 0.02 |

| 3 | M. chamomilla | 27 ± 0.05 | 0.42 ± 0.00 | 0.97 ± 0.01 | 6.26 ± 0.11 | 0.35 ± 0.04 |

| 4 | S. benzoin | 19.77 ± 0.16 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 1.02 ± 0.05 | 0.41 ± 0.01 |

| 5 | S. indicum | 35 ± 0.87 | 0.14 ± 0.00 | 0.30 ± 0.05 | 1.13 ± 0.06 | 0.59 ± 0.02 |

The phytochemical content and antioxidant activity of hydroalcoholic extracts from F. asafoetida, H. niger, M. chamomilla, S. benzoin, and S. indicum. M. chamomilla exhibited the highest phenolic content at 6.26 ± 0.11 GAE/g and the highest total flavonoid content at 1.35 ± 0.04 mg quercetin equivalents as shown in table 2. In contrast, F. asafoetida had the lowest phenolic content at 0.29 ± 0.02 GAE/g but showed a relatively good ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) activity, with values ranging from 0.19 to 5.23 µg/mL. All plant extracts demonstrated antioxidant potential across the DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, and nitric oxide (NO) scavenging assays, with IC₅₀ varying among the plants, reflecting their differing levels of antioxidant efficiency.

Evaluation of Antioxidant activity of extract

Free radical scavenging assays

|

Figure 1: The graph illustrates the IC₅₀ (µg/mL) ± SD (n = 3) for DPPH, ABTS, and Nitric Oxide free radical scavenging assays, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05. Click here to view Figure |

The ABTS, DPPH, and nitric oxide (NO) IC50 values of the hydroalcoholic extracts showed significant variations in antioxidant activity. H. niger exhibited the lowest DPPH IC50 of 2.01 µg/mL, while F. asafoetida had the highest IC50 of 4.67 µg/mL. In the ABTS assay, F. asafoetida displayed the lowest IC50 of 1.7 µg/mL, whereas S. benzoin recorded the highest IC50 of 3.76 µg/mL, For NO scavenging, the IC50 values ranged from 0.92 µg/mL to 3.91 µg/mL, demonstrating notable differences in nitric oxide neutralization efficiency. M. chamomilla showed the lowest IC50 of 0.92 µg/mL, while S. benzoin had the highest IC50 of 3.91 µg/mL. Lower IC50 values indicate higher antioxidant activity.

Reducing antioxidant power assay (FRAP assay)

|

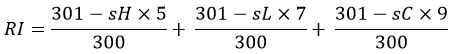

Figure 2: Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) of the hydroalcoholic extracts. n=3 with statistical significance set at p < 0.05.Click here to view Figure |

FRAP (Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power) activity of the hydroalcoholic extracts varied among the tested samples shown in figure 2, reflecting differences in their ferric-reducing potential. M. chamomilla exhibited the highest FRAP activity at 8.9 Trolox equivalent units, indicating its superior electron-donating ability. In contrast, H. niger showed the lowest activity at 3.74 Trolox equivalent units, suggesting comparatively weaker reducing power. The remaining extracts demonstrated moderate FRAP activity, with S. indicum at 5.23 Trolox equivalent units, S. benzoin at 4.99 Trolox equivalent units, and F. asafoetida at 3.9 Trolox equivalent units. Trolox, used as a reference standard.

Lipid peroxidation assay

|

Figure 3: The bar graph represents the MDA content (μg/mg extract) of hydroalcoholic extracts from different plant sources. The data is expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for n = 3, and statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05.Click here to view Figure |

The measured thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (TBARS) in hydroalcoholic extracts showed interspecies variation, with S. indicum exhibiting the highest signal (0.248 μg TBA-MDA equivalents/mg extract), followed by F. asafoetida (0.224 μg/mg), H. niger (0.154 μg/mg), S. benzoin (0.136 μg/mg), and M. chamomilla (0.104 μg/mg).

Investigation of H2O2-Mediated DNA Damage Using DNA Nicking Assay

|

Figure 4: Lane 1&2 – DNA & DNA+H2O2, Lane 3&4 – DNA+ M. chamomilla & DNA+ H2O2 + M. chamomilla, Lane 5&6 – DNA+ F. asafoetida & DNA+ H2O2+ F. asafoetida, Lane 7&8 – DNA+ H. niger & DNA+ H2O2+ H. niger, Lane 9&10 – DNA+ S. benzoin & DNA+ H2O2+ S. benzoin, Lane 11&12 – DNA+ S. indicum & DNA+ H2O2+ S. indicum.Click here to view Figure |

The gel electrophoresis image demonstrates the effect of hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) on DNA integrity and the potential protective role of various plant extracts as shown in figure 4. Lane 1 shows intact DNA, indicating no damage. In contrast, Lane 2 exhibits significant smearing, reflecting severe oxidative damage caused by H₂O₂. Lanes 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11 display well-defined bands, suggesting that M. chamomilla, F. asafoetida, H. niger, S. benzoin, and S. indicum do not degrade DNA under normal conditions.

The lanes containing DNA treated with both H₂O₂ and plant extracts (Lanes 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12) show varying levels of protection against oxidative damage. Lanes 4, 6, 8, and 10 exhibit reduced smearing compared to Lane 2, indicating the antioxidant properties of the corresponding plant extracts, which likely mitigated the oxidative stress. However, Lane 12 shows persistent smearing, suggesting that the extract from S. indicum was not effective in preventing DNA damage caused by H₂O₂.

Irritation and toxicity assay: HET-CAM (Hen’s Egg Test – Chorioallantoic Membrane) assay

The HET-CAM test is widely used as an alternative to in-vivo ocular irritation studies. It has lately been used as a preliminary screening tool to determine the irritating potential of compounds on membranes and skin prior to in-vivo testing.

Table 3: Irritation scores and classification of plant extracts.

| Sr. No. | Treatment | Irritation Score (RSD%) | Classification |

| 1 | 0.9% NaCl | 0.4 | Non irritating |

| 2 | 0.1 M NaOH | 18.77 | Extremely irritating |

| 3 | 1% sodium lauryl sulfate | 17.15 | Extremely irritating |

| 4 | M. chamomilla | 0.49 | Non irritating |

| 5 | F. asafoetida | 0.92 | Non irritating |

| 6 | H. niger | 0.54 | Non irritating |

| 7 | S. benzoin | 0.84 | Non irritating |

| 8 | S. indicum | 0.55 | Non irritating |

The HET-CAM (Hen’s Egg Chorioallantoic Membrane) assay was performed to evaluate the irritation potential of various plant extracts compared to standard irritants and a negative control. The results were expressed as the Irritation Score (IS). The standard irritants, 0.1 M NaOH and 1% sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS), had IS values of 18.77 and 17.15, respectively, categorizing them as extremely irritating. In contrast, the negative control, 0.9% NaCl, exhibited an IS of 0.4, indicating a non-irritating effect.

Among the plant extracts, M. chamomilla (IS = 0.49), F. asafoetida (IS = 0.92), H. niger (IS = 0.54), S. benzoin (IS = 0.84), and S. indicum (IS = 0.55) were all classified as non-irritating. The study was performed with a sample size of n = 3, and statistical analysis confirmed the significance of the results with a p-value < 0.05.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy studies

The various functional groups of the bioactive compound present in the plant extracts were analyzed by FTIR spectroscopy. Every spectral peak indicates the individual function groups and the intensity of the peaks indicates the quantity of that functional group containing compounds. The FTIR spectra of the hydroalcoholic extracts of F. asafoetida, H. niger, M. chamomilla, S. indicum, and S. benzoin, represents the existence of diverse functional groups in the extract which indicates the presence of various phytochemicals. The spectra show a common peak around 3400 cm-1 indicates the presence of -OH stretching, confirms alcoholic and phenolic compounds, and peaks in the range 2920-2780 cm-1 indicates the aliphatic and aromatic C-H stretching. A strong absorption peak is observed in the range of 1740- 1520 cm-1 indicates the carbonyl (C=O), alkene (C=C), confirms the presence of esters, ketones and conjugated systems. Peaks in 1250-1000 cm-1 indicate (C-O) stretching associated with alcohol, esters and ethers. The peak between 700-600 cm-1 confirms (C-X) halogen bonds, indicating halogenated compounds.

Discussion

Natural products have long been regarded as significant sources of bioactive chemicals with medicinal applications. In considering raising concerns about the adverse effects of synthetic medications, plant-based formulations provide safer and more sustainable alternatives. The hydroalcoholic extracts from F. asafoetida, H. niger, M. chamomilla, S. benzoin, and S. indicum exhibited considerable differences in extractive yields, reflecting their distinct phytochemical compositions. The notable yield from F. asafoetida can be attributed to its resinous nature, which shows high solubility in hydroalcoholic solvents. Phytochemical screening identified carbohydrates, flavonoids, and phenols in most extracts, indicating a shared antioxidant potential.24 The presence of steroids in M. chamomilla suggests additional pharmacological applications, particularly in inflammation management. Likewise, the detection of glycosides in F. asafoetida supports its traditional use in treating oxidative stress and inflammation. These findings are consistent with previous reports highlighting the therapeutic properties of plant-derived bioactive compounds.25,26

A strong correlation between total phenolic, flavonoid content and the antioxidant activity was observed. Plants such as M. chamomilla and H. niger shows high TPC and TFC exhibits better antioxidant activity in 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) (ABTS), Nitric Oxide (NO), Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) and Lipid Peroxidation (LPO) assays. Phenolic compounds are well known for their electron donating ability, which leads to free radical neutralization. While flavonoids stabilize the reactive oxygen species (ROS). F. asafoetida, S. indicum and S. benzoin show moderate antioxidant activity but it increases with increase in the concentration this observation may be due to presence of distant bioactive cells that does not participate in the free radical scavenging and neutralizing the free radicals. The nitric oxide (NO) scavenging assay further confirmed the antioxidant capacity of the extracts, indicating their ability to neutralize reactive nitrogen species. Extracts with higher flavonoid and phenolic content, particularly M. chamomilla, showed superior NO scavenging effects, consistent with the reduction in oxidative stress biomarkers.27,28

Lipid peroxidation levels, determined by estimated malondialdehyde (MDA) content, gives additional interpretation into antioxidant potential. The MDA levels in M. chamomilla highlights strong antioxidant potential. It reduces lipid peroxidation and enhances protection against oxidative stress. H. niger and S. benzoin shows moderate MDA content indicates that it may be not as effective as M. chamomilla in lipid peroxidation. F. asafoetida and S. indicum show slightly elevated MDA content that highlights more lipid peroxidation may be due to the high concentration of extract, indicating greater oxidative stress and lower intrinsic antioxidant protection within these plant extracts.27,29

The DNA nicking assay evaluates the efficacy of the plant extracts in reducing and preventing oxidative DNA damage caused by H2O2 induced oxidative stress. The plant extracts neutralize the peroxidative damage to DNA by neutralizing the peroxide and due to this it reduces the DNA fragmentation. The extracts M. chamomilla, F. asafoetida, H. niger, and S. benzoin indicate notable antioxidant protection, possibly due to their polyphenol and flavonoid content.30

HET-CAM assay results indicate the toxicity of the plant extracts for topical applications including eyes. All plant extracts were classified as non-irritating, with M. chamomilla showing the lowest and H. niger and S. indicium almost show equal irritation score, supporting its potential use in skincare and pharmaceutical products. While the slightly higher irritation scores of F. asafoetida and S. benzoin may be due to their sulphur containing compounds or some other aromatic compounds like benzoic acid but still, they remained within the non-irritating range.

The FTIR spectrum indicates the presence of the functional groups that can indicate the presences of bioactive compounds like quercetin, ferulic acid, umbelliferon, scopolamine, benzoic acid and sesamol, these biomarkers are highlighted due their reported health benefit in medical sciences. Notably, the F. asafoetida FTIR spectrum indicates phenolic compounds like ferulic acid and other compounds such as umbelliferon. H. niger and M. chamomilla show alkaloids like scopolamine and quercetin respectively. S. indicum shows phenolic lignans like sesamol. S. benzoin shows polyphenol like benzoic acid.

The hydroalcoholic extracts demonstrated various antioxidant and protective properties, these plants can be used in many therapeutics because of their superior antioxidant efficacy, high phenolic and flavonoid content, and safety profile. These results demonstrate and highlight that the plant base drugs are more efficient in terms of cost, efficacy and in low toxicity. Further research focusing on in-vivo efficacy, identification of biomarkers responsible for many therapeutic benefits, the isolation and characterization of specific bioactive compounds could enhance the understanding of their therapeutic mechanisms.

Conclusion

The study evaluates the phytochemical composition, antioxidant potential and toxicity analysis of hydroalcoholic extracts of F. asafoetida, H. niger, M. chamomilla, S. benzoin, and S. indicum. F. asafoetida showed the highest extractive yield (46.33%), while S. benzoin had the lowest (19.77%). Phytochemical analysis confirms the presence of carbohydrates, proteins, flavonoids, and phenols. Antioxidant assays revealed significant activity, H. niger shows the highest DPPH scavenging (IC50 = 2.01 µg/mL), M. chamomilla show highest nitric oxide scavenging (IC50 = 0.92 µg/mL) and F. asafoetida shows highest ABTS scavenging activity (IC50 = 1.7 µg/mL). M. chamomilla showing the highest FRAP (8.9 Trolox equivalents) and lowest MDA content (0.104 μg/mg extract), indicating lowest lipid peroxidation potential. The HET-CAM assay classified that the plant extracts as non-irritating, supporting their safety for topical and oral use. These results suggest their potential as a natural antioxidant for pharmaceutical and cosmetic applications. Further suggesting in-vivo studies to investigate and validate the therapeutic efficacy and toxicity. However, additional studies focusing on their mechanistic pathways, and in-vivo therapeutic efficacy will be crucial to unlocking their full potential in disease prevention and treatment.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to extend our sincere thanks to DST-FIST and University of Mumbai for providing necessary infrastructure during the course of this study.

Funding Sources

This study was funded by the Central Council for Research in Unani Medicine (CCRUM), Ministry of AYUSH, Government of India (Grant number: F. No. 3-70/2020-CCRUM/Tech.).

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

This statement does not apply to this article.

Ethics Statement

This research did not involve human participants, animal subjects, or any material that requires ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not involve human participants, and therefore, informed consent was not required.

Clinical Trial Registration

This research does not involve any clinical trials.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

Not Applicable

Author Contributions

Falak Bamne: Methodology, Investigation, Writing.

Pawan Sharma: Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Validation, Writing.

Ahmad Ali: Conceptualization, Supervision, Methodology, Resources.

Munira Momin: Validation, Supervision.

Tabassum Khan: Visualization, Data Presentation, Literature Review.

Nikhat Shaikh: Methodology, Formal Analysis.

References

- Ali A. Herbs that heal: The philanthropic behaviour of nature. Ann Phytomed. 2020;9(1):7–17. doi:10.21276/ap.2020.9.1.2

CrossRef - Bagheri SM, Hedesh ST, Mirjalili A, Dashti-R MH. Evaluation of anti-inflammatory and some possible mechanisms of antinociceptive effect of Ferula asafoetida oleo gum resin. J Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2016;21:271–276. doi:10.1177/2156587215605903

CrossRef - Gopika GG, Gayathri R, Priya VV, Selvaraj J, Kavitha S. Antioxidant and xanthine oxidase inhibitory potential of aqueous extract of Ferula asafoetida. J Pharm Res Int. 2021;33:166–173. doi:10.9734/jpri/2021/v33i57B34042

CrossRef - İnci Ş, Sancar PY, Demirpolat A, Kirbag S, Civelek S. Chemical compositions of essential oils, antimicrobial effect and antioxidant activity studies of Hyoscyamus niger from Turkey. bioRxiv. 2022. doi:10.1101/2022.08.07.503024

CrossRef - Kolodziejczyk-Czepas J, Bijak M, Saluk J, Ponczek MB, Zbikowska HM, Nowak P, Tsirigotis-Maniecka M, Pawlaczyk I. Radical scavenging and antioxidant effects of Matricaria chamomilla polyphenolic-polysaccharide conjugates. Int J Biol Macromol. 2015;72:1152–1158. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014. 09.032

CrossRef - Wei P, Zhao F, Wang Z, Wang Q, Chai X, Hou G, Meng Q. Sesamum indicum: A comprehensive review of nutritional value, phytochemical composition, health benefits, development of food, and industrial applications. Nutrients. 2022;14:4079. doi:10.3390/nu14194079

CrossRef - Elfiati D, Faulina SA, Rahayu LM, Aryanto A, Dewi RT, Rachmat HH, Turjaman M, Royyani MF, Susilowati A, Hidayat AC. Culturable endophytic fungal assemblages from Styrax sumatrana and Stryax benzoin and their potential as antifungal, antioxidant, and alpha-glucosidase inhibitory resources. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:974526. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2022.974526

CrossRef - Manova V, Gruszka D. DNA damage and repair in plants – from models to crops. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:885. doi:10.3389/fpls.2015.00885

CrossRef - Bamne F, Shaikh N, Momin M, Khan T, Ali A. Phytochemical analysis, antioxidant and DNA nicking protection assay of some selected medicinal plants. Ann Phytomed. 2023;12(2):406–413. doi:10.54085/ap.2023.12.2.50

CrossRef - Dubale S, Kebebe D, Zeynudin A, Abdissa N, Suleman S. Phytochemical screening and antimicrobial activity evaluation of selected medicinal plants in Ethiopia. J Exp Pharmacol. 2023;15:51–62. doi:10.2147/JEP.S379805

CrossRef - Gusakov AV, Kondratyeva EG, Sinitsyn AP. Comparison of two methods for assaying reducing sugars in the determination of carbohydrase activities. Int J Anal Chem. 2011;2011:1–4. doi:10.1155/2011/283658

CrossRef - Bradford M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi:10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3

CrossRef - Lu X, Wang J, Al-Qadiri HM, Ross CF, Powers JR, Tang J, Rasco BA. Determination of total phenolic content and antioxidant capacity of onion (Allium cepa) and shallot (Allium oschaninii) using infrared spectroscopy. Food Chem. 2011;129:637–644. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.04.105

CrossRef - Balyan P, Ali A. Comparative analysis of the biological activities of different extracts of Nigella sativa seeds. Ann Phytomed. 2022;11:67. doi:10.54085/ap.2022.11.1.67

CrossRef - Ghafar F, Nazrin TNNT, Salleh MRM, Hadi NN, Ahmad N, Hamzah AA, Yusof ZAM, Azman IN. Total phenolic content and total flavonoid content in Moringa oleifera Sci Herit J. 2017;1:23–25. doi:10.26480/gws.01.2017.23.25

CrossRef - Kaur A, Shukla A, Shukla RK. Comparative evaluation of ABTS, DPPH, FRAP, nitric oxide assays for antioxidant potential, phenolic & flavonoid content of Ehretia acuminata Br. bark. Int Res J Pharm. 2019;9:100–104. doi:10.7897/2230-8407.0912301

CrossRef - Kedare SB, Singh RP. Genesis and development of DPPH method of antioxidant assay. J Food Sci Technol. 2011;48:412–422. doi:10.1007/s13197-011-0251-1

CrossRef - Baliyan S, Mukherjee R, Priyadarshini A, Vibhuti A, Gupta A, Pandey RP, Chang C. Determination of antioxidants by DPPH radical scavenging activity and quantitative phytochemical analysis of Ficus religiosa. Molecules. 2022;27:1326. doi:10.3390/molecules27041326

CrossRef - Gulcin İ, Alwasel SH. DPPH radical scavenging assay. Processes. 2023;11:2248. doi:10.3390/pr11082248

CrossRef - Baliga MS, Jagetia GC, Rao SK, Babu SK. Evaluation of nitric oxide scavenging activity of certain spices in vitro: A preliminary study. Nahrung. 2003;47:261–264. doi:10.1002/food.200390061

CrossRef - Paramanya A, Ali A. Effect of Arthrospira platensis extracts on glycation of BSA. Acta Biol Szeged. 2025;68:23–30. doi:10.14232/abs.2024.1.23-30

CrossRef - Zeb A, Ullah F. A simple spectrophotometric method for the determination of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances in fried fast foods. J Anal Methods Chem. 2016;2016:1–5. doi:10.1155/2016/9412767

CrossRef - DB-ALM Protocol No. 47: HET-CAM Test for Eye Irritation. Eur Cent Valid Altern Methods (ECVAM). 2007. Available from: https://ecvam-dbalm.jrc.ec.europa.eu/methods-and-protocols/protocols

- Khan S, Rehman MU, Khan MZI, Kousar R, Muhammad K, Haq IU, Khan MI, Almasoud N, Alomar TS, Rauf A. In vitro and in vivo antioxidant therapeutic evaluation of phytochemicals from different parts of Dodonaea viscosa Front Chem. 2023;11:1268949. doi:10.3389/fchem.2023.1268949

CrossRef - Mihyaoui AE, Da Silva JC, Charfi S, Castillo MC, Lamarti A, Arnao MB. Matricaria chamomilla: A review of ethnomedicinal use, phytochemistry and pharmacological uses. Life. 2022;12:479. doi:10.3390/life12040479

CrossRef - Kamran SKS, Rasul A, Anwar H, Irfan S, Ullah KS, Malik SA, Razzaq A, Aziz N, Braidy N, Hussain G. Ferula asafoetida is effective for early functional recovery following mechanically induced insult to the sciatic nerve of a mouse model. Trop J Pharm Res. 2020;19:1903–1910. doi:10.4314/tjpr.v19i9.15

CrossRef - Niazmand R, Razavizadeh BM. Ferula asafoetida: Chemical composition, thermal behavior, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of leaf and gum hydroalcoholic extracts. J Food Sci Technol. 2020;58:2148–2159. doi:10.1007/s13197-020-04724-8

CrossRef - Mihyaoui AE, Castillo MIEC, Cano A, Hernandez-Ruiz J, Lamarti A, Arnao MB. Comparative study of wild chamomile plants from the north-west of Morocco: Bioactive components and total antioxidant activity. J Med Plants Res. 2021;5:431–441. doi:10.5897/JMPR2021.7159

- Tsikas D. Assessment of lipid peroxidation by measuring malondialdehyde (MDA) and relatives in biological samples: Analytical and biological challenges. Anal Biochem. 2017;524:13–30. doi:10.1016/j.ab.2016.10.021

CrossRef - Kolodziejczyk-Czepas J, Bijak M, Saluk J, Ponczek MB, Zbikowska HM, Nowak P, Tsirigotis-Maniecka M, Pawlaczyk I. Radical scavenging and antioxidant effects of Matricaria chamomilla polyphenolic-polysaccharide conjugates. Int J Biol Macromol. 2015;72:1152–1158. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.09.032

CrossRef

Abbreviations List

Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA),

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR),

Hen’s Egg Test on the Chorioallantoic Membrane (HET-CAM).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.