Manuscript accepted on : 25-06-2025

Published online on: 08-07-2025

Plagiarism Check: Yes

Reviewed by: Dr. Catarina Matos

Second Review by: Dr. Nataliya Kitsera

Final Approval by: Dr. Hifzur Siddique

Targeting Oncogenic Pathways in Cancer: Therapeutic Advances, Challenges, and Future Directions

Ritika Gera1 , Rajesh Kumar1*

, Rajesh Kumar1* , Kamaljit Panchal1

, Kamaljit Panchal1 , Vikas Sharma2

, Vikas Sharma2 and Ramika Garg1

and Ramika Garg1

1Department of Biotechnology, UIET, Kurukshetra University Kurukshetra, Haryana

2Department of Biotechnology, Ambala College of Engineering and Applied Research, Devsthali, Ambala, Haryana

Corresponding Author E-mail: rkumar2015@kuk.ac.in

ABSTRACT: Cancer represents a multifaceted global health burden shaped by diverse genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors. The GLOBOCAN 2022 data emphasize the growing incidence and regional variation of cancers such as breast, lung, colorectal, and oral malignancies. Underlying this burden are complex oncogenic signaling pathways—including Wnt/β-catenin, Notch, Hedgehog, PI3K/AKT/mTOR, and JAK/STAT—that regulate cell proliferation, apoptosis, and metastasis. While therapeutic interventions targeting these pathways have shown promise, durable clinical outcomes remain limited due to pathway redundancy, crosstalk, and tumor heterogeneity. This review systematically explores these signaling networks, detailing current and investigational therapeutic targets and the clinical progress of pathway-specific inhibitors. We identify critical gaps in translating molecular insights into personalized therapies and emphasize the need for integrated, multi-targeted approaches. By synthesizing recent advances in molecular oncology and emerging therapeutic strategies, this work offers a forward-looking perspective on overcoming current challenges and optimizing cancer treatment paradigms.

KEYWORDS: Cancer types; Global Burden; Malignancies; Molecular Pathways; Signaling

| Copy the following to cite this article: Gera R, Kumar R, Panchal K, Sharma V, Garg R. Targeting Oncogenic Pathways in Cancer: Therapeutic Advances, Challenges, and Future Directions. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(3). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Gera R, Kumar R, Panchal K, Sharma V, Garg R. Targeting Oncogenic Pathways in Cancer: Therapeutic Advances, Challenges, and Future Directions. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(3). |

Introduction

Cancer is a biologically complex and multifactorial disease characterized by the uncontrolled proliferation and spread of abnormal cells. It arises from a combination of genetic mutations, environmental exposures, lifestyle factors, and infectious agents.1 Despite the diverse triggers, a common hallmark across all cancer types is the disruption of regulatory mechanisms governing cell growth, division, and apoptosis—resulting in malignant tumor formation and potential metastasis.2,3

Globally, cancer poses a major public health burden, transcending geographic and socioeconomic boundaries. According to recent estimates, its growing incidence and mortality exert significant pressure on healthcare systems, economies, and the quality of life worldwide.4,5 This challenge necessitates an integrated, multidisciplinary response that combines scientific research, clinical practice, and public health policy.4

Over the past decades, advancements in genomics, molecular biology, and epidemiology have enhanced our understanding of cancer etiology and risk. Modifiable factors such as tobacco use, poor diet, physical inactivity, and exposure to carcinogens, along with non-modifiable factors like age and genetic predisposition, collectively influence cancer risk.6 Prevention strategies—including lifestyle interventions, environmental regulations, and vaccination programs against oncogenic infections—have become key tools in reducing incidence.7

Meanwhile, the emergence of targeted therapies, immunotherapies, and precision medicine has transformed cancer treatment paradigms. Yet, tumor heterogeneity and the complexity of molecular alterations continue to challenge therapeutic effectiveness.7,8 To address this, a deeper exploration of the cellular and molecular pathways that drive cancer is essential.

This review provides a focused overview of the global cancer burden and delves into the core biological mechanisms of tumor progression. It highlights five major oncogenic pathways—Wnt/β-catenin, Notch, Hedgehog, PI3K/AKT/mTOR, and JAK/STAT—and evaluates their relevance as therapeutic targets. By synthesizing current knowledge and clinical advances, this review aims to inform future strategies for cancer treatment and contribute to the evolving landscape of precision oncology.

Literature Search Methodology

To ensure comprehensive coverage of the subject matter, a detailed literature search was conducted using multiple scientific databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. The search strategy was designed to identify peer-reviewed publications relevant to cancer signaling pathways and therapeutic interventions, with a particular focus on five major pathways: Wnt/β-catenin, Notch, Hedgehog, PI3K/AKT/mTOR, and JAK/STAT. The search included studies published between January 2010 and April 2024, using combinations of keywords such as “cancer signaling pathways,” “targeted therapy,” “Wnt inhibitors,” “Notch signaling in cancer,” “Hedgehog pathway antagonists,” “PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibitors,” and “JAK/STAT pathway blockade.” Only articles published in English were considered. Studies were selected based on their relevance to therapeutic targeting in cancer, with a preference for original research, systematic reviews, and clinical trial reports. Editorials, non-peer-reviewed articles, and studies not directly related to the scope of cancer signaling or therapeutic application were excluded. The final selection of sources emphasized scientific rigor, therapeutic relevance, and recency, prioritizing high-impact journals and landmark clinical data to ensure the review provides a robust and up-to-date synthesis.

Global cancer burden

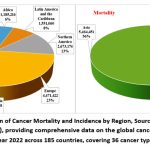

Cancer is a major threat to the health of people everywhere. Cancer poses a significant global health challenge, with approximately 19.7 million new cases and nearly 10 million deaths reported worldwide in 2022 (Fig.1).9-11 The GCO’s 2022 data reveals the global cancer burden and emphasizes the intricate interactions between hereditary, environmental, and lifestyle factors.11 The patterns of cancer incidence and mortality vary significantly across regions, underscoring the need for region-specific strategies to address this disease effectively.10,11

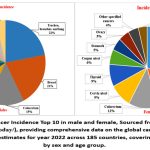

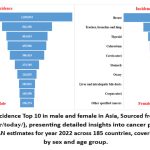

Globally, cancers of the trachea, bronchus, and lung are among the most common and are leading contributors to cancer mortality, particularly among males.10 In contrast, breast cancer remains the most prevalent cancer among females and a significant cause of cancer-related deaths (Fig.2).11 Asia, home to a substantial portion of the global population, bears the highest cancer burden (Fig.1). It accounts for a significant share of global cancer cases and deaths, with lung cancer leading as the primary cause of mortality in males and breast cancer ranking highest in incidence among females (Fig.3).10,11

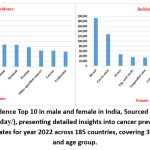

In India, the trends align with these broader patterns, with breast cancer being the most common and fatal cancer among females. For males, lip and oral cavity cancers contribute significantly to the national cancer burden (Fig.4).10,11 These variations emphasize the importance of tailored public health strategies to address specific cancer types within distinct demographic and geographic contexts.

Hallmarks of Cancer

Cancer cells exhibit a range of distinctive capabilities that enable tumor initiation, progression, and metastasis. These hallmark traits, first described by Hanahan and Weinberg, include sustaining proliferative signaling, evading growth suppressors, resisting cell death, enabling replicative immortality, inducing angiogenesis, activating invasion and metastasis, reprogramming energy metabolism, and avoiding immune destruction. Additional emerging traits include genome instability, tumor-promoting inflammation, phenotypic plasticity, and non-mutational epigenetic reprogramming.12-15

Sustaining Proliferative Signaling

Cancer cells acquire the ability to sustain chronic proliferation through mutations or overexpression of growth factor receptors (e.g., EGFR) and downstream signaling molecules (e.g., Ras, PI3K/AKT, MAPK).12,13,15 These alterations decouple growth from external cues, supporting genomic instability and unchecked division.14,16-18 Activating mutations in proto-oncogenes such as Ras and EGFR are among the most common drivers of this hallmark and are found in a significant proportion of lung, colon, and pancreatic cancers.19-26 Targeted therapies such as Trastuzumab for HER2/neu and MEK inhibitors for Ras-driven tumors exemplify approaches that exploit this hallmark.27-29

Evading Growth Suppressors

Mutations in tumor suppressor genes such as TP53 and RB1 disrupt cellular checkpoints that prevent proliferation under stress or DNA damage. Their loss facilitates unchecked growth and genomic instability.12,13,15,29 Other tumor suppressors frequently inactivated in cancer include DPC4, which regulates TGF-β signaling, and NF1, which normally inhibits Ras signaling. Loss of these regulators is associated with tumor progression in several cancers, including colon and neurofibromatosis-associated malignancies.30-33

Resisting Cell Death

Cancer cells often bypass apoptotic mechanisms by upregulating anti-apoptotic proteins (e.g., BCL-2) or downregulating pro-apoptotic factors, contributing to treatment resistance and tumor survival.14,15 Restoration of tumor suppressor function, particularly p53, remains a therapeutic goal. Experimental compounds like PRIMA-1 and MIRA-1 aim to reactivate p53 function in mutated tumors, although clinical application remains challenging.28,34

Enabling Replicative Immortality

Tumors achieve limitless replicative potential through telomerase reactivation, enabling cancer cells to bypass senescence and divide indefinitely.12,14

Inducing Angiogenesis

To meet high metabolic demands, tumors secrete pro-angiogenic factors like VEGF, stimulating the formation of new blood vessels. However, this neo vasculature is often abnormal, contributing to hypoxia and therapeutic barriers.12,14

Activating Invasion and Metastasis

Cancer cells undergo epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), gaining motility and the ability to degrade extracellular matrices, facilitating metastasis to distant sites.12-15,

Deregulating Cellular Energetics

Tumor cells favor aerobic glycolysis (the Warburg effect) over oxidative phosphorylation even in oxygen-rich conditions, enabling them to thrive in hypoxic, nutrient-poor environments.12-14,16

Avoiding Immune Destruction

Cancer cells evade immune surveillance by expressing immune checkpoint molecules (e.g., PD-L1) or recruiting immunosuppressive cells, creating an immune-privileged tumor microenvironment.12-15

Genome Instability and Mutation

Defects in DNA repair pathways (e.g., BRCA1/2 mutations) result in elevated mutation rates, increasing the likelihood of oncogenic alterations.12,13,15 Genomic instability is also exacerbated by DNA replication errors, chromatin remodeling defects, and epigenetic dysregulation.17

Tumor-Promoting Inflammation

Chronic inflammation releases cytokines and reactive oxygen species that promote DNA damage, proliferation, and metastasis.12-15

Unlocking Phenotypic Plasticity

Cancer cells can transition between phenotypes, enabling adaptation to environmental changes and contributing to therapeutic resistance.12-14

Non-Mutational Epigenetic Reprogramming

Altered DNA methylation and histone modifications can silence tumor suppressor genes or activate oncogenes without changing DNA sequences, driving malignancy.12-14

Disruption of Cell Cycle Regulation

Dysregulation of cyclins (e.g., cyclin D, cyclin E) and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK4/6) enables unchecked progression through the cell cycle.35-39 Loss of checkpoint proteins such as p21 and p27, along with inactivation of p53 and RB1, disables critical cell cycle arrest mechanisms that typically respond to DNA damage and genomic instability.36,37 These defects allow cancer cells to bypass the G1/S checkpoint, resulting in uncontrolled proliferation. In some cancers, such as breast cancer, overexpression of cyclin E leads to premature S-phase entry and replication stress. Targeted therapies like CDK4/6 inhibitors (e.g., Palbociclib) aim to restore control over these deregulated checkpoints and have shown clinical efficacy, particularly in hormone receptor-positive breast cancer.38,39

Collectively, these hallmark traits represent the biological foundation of cancer and are sustained by complex networks of dysregulated signaling pathways. Rather than operating in isolation, these traits are often interconnected and reinforced by aberrant molecular cascades that regulate cell proliferation, survival, angiogenesis, immune evasion, and metastasis. Central among these are the Wnt/β-catenin, Notch, Hedgehog, PI3K/AKT/mTOR, and JAK/STAT pathways, which act as key molecular drivers behind many of these malignant capabilities. Understanding how these pathways intersect with specific hallmarks is essential for developing more effective and precise therapeutic strategies.

Pathways responsible for cancer development and their therapeutic targets:

Genetic and epigenetic alterations that impair regular cellular processes, permitting unchecked cell proliferation and evasion of the body’s natural survival and migratory restrictions, are the cause of cancer’s formation and spread. These alterations affect the pathways that regulate cell division, growth, fate, and movement. Additionally, they support wider networks that influence the course of cancer development.40-42 This includes angiogenesis, inflammation, changes in the tumor microenvironment, and resistance to radiation and chemotherapy. The alteration in pathways including NOTCH, WNT, Hedgehog, PI3K/AKT/mTOR, or JAK-STAT can give cancer cells multiple functions such drug efflux, activation of stem cell genes, and resilient to senescence and programmed cell death.42,43 However, these pathways are complex, interrelated, and regulated by feedforward and feedback and hence it will be difficult to create treatments that target one pathway while ignoring others.44,45

Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is a highly conserved cascade essential for embryonic development, tissue homeostasis, and stem cell renewal.44,46,47 In the canonical pathway, Wnt ligands bind to Frizzled (FZD) receptors and LRP5/6 co-receptors, inhibiting the β-catenin destruction complex composed of Axin, APC, and GSK-3β. This inhibition stabilizes β-catenin, allowing it to accumulate in the cytoplasm and translocate to the nucleus, where it activates transcription of target genes involved in proliferation and survival.44,48-50

Aberrant activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway contributes to the initiation and progression of various cancers, including colorectal, breast, liver, and melanoma. Mutations in APC, CTNNB1 (encoding β-catenin), or other components result in constitutive activation, leading to unchecked cellular proliferation, invasion, and resistance to apoptosis.51,52,53 Multiple therapeutic strategies are being explored to inhibit the Wnt/β-catenin pathway (Table 1):

PORCN inhibitors, such as LGK974, WNT974, ETC-1922159, RXC004, and CGX1321 (with pembrolizumab) prevent the palmitoylation and secretion of Wnt ligands, limiting pathway activation in tumors such as melanoma, breast, pancreatic, and gastrointestinal cancers.44,55

Frizzled receptor antagonists, including OMP-18R5 and OTSA101-DTPA-90Y, block Wnt ligand binding and receptor activation.44

FZD8 decoy receptors, such as OMP-54F28, act as soluble traps for Wnt ligands, showing early promise in liver, pancreatic, and ovarian cancers.44

CBP/β-catenin antagonists like PRI-724 and β-catenin gene expression inhibitors like SM08502 inhibit downstream transcriptional activity, targeting cancers such as pancreatic and solid tumors.44

Wnt5a mimetic agents like Foxy-5 modulate non-canonical Wnt signaling and are under investigation in colon cancer.54

Wnt ligand inhibitors, such as Plumbagin, have shown preclinical efficacy in endocrine-resistant breast cancer models.44

Several of these agents are in various phases of clinical trials, from preclinical to phase II.44,48-54 While these approaches have demonstrated potential, challenges remain, particularly due to the essential role of Wnt signaling in normal tissue regeneration, leading to toxicity concerns. Resistance mechanisms and biomarker identification for patient stratification are ongoing hurdles.44,53-55 Selective and combinational targeting of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway—guided by predictive biomarkers—offers a promising direction for precision oncology. Further research is needed to enhance target specificity and mitigate off-target effects in non-tumor tissues.

Notch Signaling Pathway

The Notch signaling pathway is a critical mediator of cell fate decisions, differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis.44,56 It operates through direct cell-to-cell communication: when Notch ligands (e.g., Jagged or Delta-like) from one cell bind to Notch receptors on an adjacent cell, the receptor undergoes proteolytic cleavage by γ-secretase, releasing the Notch intracellular domain (NICD). The NICD translocates to the nucleus and activates gene transcription by interacting with CSL transcription factors. Dysregulated Notch signaling has been implicated in both oncogenic and tumor-suppressive roles, depending on cellular context and cancer type. Constitutive Notch activation promotes tumor progression in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL), breast cancer, colorectal cancer, and pancreatic cancer. Conversely, Notch can suppress tumors in certain squamous cell carcinomas.44,56,57 Efforts to therapeutically modulate Notch signaling have yielded several investigational approaches (Table 1):

γ-Secretase inhibitors (GSIs), such as PF-03084014, BMS-906024, MK-0752, and RO4929097, prevent NICD release and inhibit downstream transcription. These agents are under investigation across a variety of cancers, including T-ALL, breast, renal, pancreatic, and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).57,58,59

Monoclonal antibodies, including Enoticumab, Demcizumab, Tarextumab, and Brontictuzumab, target Notch receptors or ligands to disrupt pathway activation. They are being evaluated in solid and hematological malignancies, such as ovarian, pancreatic, lung, and breast cancers.33,57

DLL3-targeting agents, notably rovalpituzumab tesirine, have shown activity in neuroendocrine carcinomas like small cell lung cancer.58,59

CB-103, a newer investigational agent, disrupts Notch transcriptional activation and is being studied in both solid and hematological cancers.58,59 Several GSIs and monoclonal antibodies have progressed to early-phase clinical trials. Although some show activity in hematologic and solid tumors, dose-limiting gastrointestinal toxicities (due to inhibition of Notch in intestinal epithelium) have limited clinical utility. Moreover, dual roles of Notch in tumorigenesis necessitate precise context-specific targeting. Future strategies must prioritize targeted delivery systems, biomarker-based patient stratification, and combination therapies to harness the pathway’s therapeutic potential while mitigating adverse effects. The continued development of agents such as CB-103 and antibody-drug

Hedgehog (Hh) Signaling Pathway

The Hedgehog (Hh) signaling pathway plays a vital role in embryonic development, tissue regeneration, and stem cell maintenance.48,60,61 The pathway is initiated when Hh ligands (Sonic, Indian, or Desert Hedgehog) bind to the Patched (PTCH) receptor, relieving its inhibition of Smoothened (SMO), a G-protein-coupled receptor-like protein. Activated SMO triggers intracellular signaling cascades that activate GLI transcription factors, which regulate target gene expression. Aberrant Hh signaling is implicated in the pathogenesis of various cancers, particularly basal cell carcinoma (BCC), medulloblastoma, pancreatic, and prostate cancers. Mutations in PTCH or activating mutations in SMO can lead to ligand-independent constitutive pathway activation, driving proliferation and tumorigenesis.60-63

Several inhibitors have been developed to target key components of the Hh pathway (Table 1):

SMO inhibitors, including vismodegib, sonidegib, and glasdegib, block the activation of downstream signaling and are approved or under evaluation for BCC, medulloblastoma, and pancreatic cancer.48,60-63

GLI inhibitors, such as GANT61, arsenic trioxide, and itch inhibitors, target the final effectors of the pathway and are under preclinical or early-stage investigation for medulloblastoma, pancreatic, and other cancers. 48,60-63

PTCH inhibitors and antibody-based therapies, like 5E1 (anti-Shh antibody) and GDC-0449 (anti-SMO antibody), provide additional mechanisms for blocking upstream components of the pathway. 48,60-63

Downstream pathway modulators, such as BMS-833923 and other GLI antagonists, are being explored for various solid tumors, including breast, lung, and pancreatic cancers. 48,60-63

SMO inhibitors like vismodegib and sonidegib have received FDA approval for advanced BCC and have shown efficacy in clinical trials for other cancers. However, resistance—often via downstream mutations or GLI amplification—limits their long-term effectiveness. Toxicity, including muscle spasms and dysgeusia, also poses barriers to chronic use.

To overcome resistance and expand therapeutic applicability, next-generation Hh inhibitors targeting GLI and combination therapies with PI3K or immune checkpoint inhibitors are being explored. Precision medicine approaches based on genetic profiling may enhance patient selection and therapeutic efficacy. The development of antibody-based inhibitors and pathway-modulating agents like BMS-833923 represents promising avenues for future clinical impact.48,60-63

PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathway

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is one of the most frequently altered signaling cascades in human cancers.64 It plays a central role in regulating cell growth, survival, metabolism, and angiogenesis. Activation typically begins with receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), which stimulate phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) to convert PIP2 to PIP3, leading to the recruitment and activation of AKT. AKT subsequently activates mTOR, a master regulator of protein synthesis and cell growth.65,66

Dysregulation of this pathway is observed in a wide range of malignancies, including breast, prostate, endometrial, colorectal, and glioblastoma. Oncogenic mutations in PIK3CA (encoding the catalytic subunit of PI3K), loss of PTEN (a tumor suppressor that inhibits PI3K activity), or amplification of AKT result in constitutive pathway activation, promoting proliferation, inhibiting apoptosis, and contributing to therapy resistance.48,65-69 Several classes of inhibitors have been developed to target components of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis (Table 1):

PI3K inhibitors (e.g., idelalisib, copanlisib, alpelisib) target specific isoforms or pan-PI3K activity.65

AKT inhibitors (e.g., capivasertib, ipatasertib) block downstream signaling.66

mTOR inhibitors (e.g., everolimus, temsirolimus) inhibit mTORC1 complex activity.67,68

Dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitors (e.g., dactolisib) aim to overcome compensatory feedback loops.68

While mTOR inhibitors have received regulatory approval for certain cancers (e.g., renal cell carcinoma, breast cancer), responses are often modest and transient. Isoform-specific PI3K inhibitors (e.g., alpelisib in PIK3CA-mutant breast cancer) have demonstrated improved efficacy with manageable toxicity. However, acquired resistance, metabolic side effects (e.g., hyperglycemia), and feedback activation of alternate pathways limit broader application. Future directions include rational combination therapies (e.g., with endocrine therapy, PARP inhibitors, or immunotherapy), biomarker-driven patient selection, and deeper understanding of resistance mechanisms. Integration of this pathway into multi-omics and precision oncology frameworks may enhance its clinical utility and therapeutic impact.64-69

JAK/STAT Signaling Pathway

The Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathway is a critical mediator of cytokine signaling involved in cell proliferation, differentiation, immune regulation, and apoptosis. Upon cytokine or growth factor binding to cell surface receptors, associated JAKs become activated through phosphorylation. Activated JAKs then phosphorylate STAT transcription factors, which dimerize and translocate to the nucleus to regulate gene expression.65,69 Constitutive activation of the JAK/STAT pathway contributes to oncogenesis in hematological malignancies and various solid tumors, including breast, colorectal, liver, and head and neck cancers. Common mechanisms include mutations in JAK2 (e.g., V617F in myeloproliferative neoplasms) and persistent activation of STAT3 or STAT5, which promote tumor growth, angiogenesis, immune evasion, and resistance to apoptosis.44,48,66,70

Targeting the JAK/STAT pathway has emerged as a promising therapeutic strategy, particularly in hematologic cancers (Table 1):

JAK inhibitors (e.g., ruxolitinib, fedratinib) are approved for treating myelofibrosis and polycythemia vera.65

STAT inhibitors (e.g., stattic, napabucasin) aim to disrupt STAT3 activation and transcriptional activity.44

Cytokine receptor antagonists (e.g., tocilizumab targeting IL-6R) reduce upstream activation.66

MicroRNA modulators and epigenetic agents are being investigated for their roles in modulating STAT-driven gene expression.67

JAK inhibitors have demonstrated clinical efficacy in specific hematologic contexts but are less established in solid tumors due to toxicity and limited target selectivity.48 Resistance mechanisms, such as secondary mutations or compensatory activation of parallel pathways, remain significant hurdles. Moreover, directly targeting STAT proteins is technically challenging due to their structure and intracellular location. Future strategies will benefit from improved STAT-specific inhibitors, novel delivery mechanisms, and combination regimens that enhance anti-tumor immune responses. The JAK/STAT axis is also a key node in cancer stem cell regulation and immunosuppression, making it a valuable target for synergistic therapies involving checkpoint inhibitors or cancer vaccines.48,66-67

Table 1: Summary of Therapeutic Agents Targeting Key Oncogenic Pathways in Cancer

| Pathway | Therapeutic Target | Agent(s) | Cancer Type / Model | Trial Phase | References |

| Wnt | PORCN Inhibitor | LGK974, WNT974, ETC-1922159, RXC004, CGX1321 | Melanoma, breast, colorectal, GI cancers | Phase I–II | [44, 51, 54, 55] |

| Wnt Ligand Inhibitor | Plumbagin | Endocrine-resistant breast cancer | Preclinical | [44] | |

| Wnt5a Mimetic | Foxy-5 | Colon cancer | Phase II | [54] | |

| FZD Receptor Antagonist | OMP-18R5, OTSA101-DTPA-90Y | Breast, pancreatic, synovial sarcoma | Phase I | [44] | |

| FZD8 Decoy Receptor | OMP-54F28 | Hepatocellular, pancreatic, ovarian, solid tumors | Phase I | [44] | |

| β-catenin/CBP Antagonist | PRI-724 | Pancreatic cancer, AML, CML, solid tumors | Phase I–II | [44, 50, 51] | |

| Notch | γ-Secretase Inhibitors (GSIs) | PF-03084014, BMS-906024, MK-0752, RO4929097 | T-ALL, breast, renal, pancreatic, NSCLC | Phase I–III | [57–59] |

| Monoclonal Antibodies | Enoticumab, Demcizumab, Tarextumab, Brontictuzumab | Ovarian, pancreatic, breast, lung, hematologic cancers | Phase I–II | [33, 57–59] | |

| DLL3 Targeting Agents | Rovalpituzumab Tesirine | Small cell lung cancer | Phase II | [58, 59] | |

| CB-103 | CB-103 | Advanced solid and hematologic malignancies | Phase I–IIa | ||

| Hedgehog | SMO Inhibitors | Vismodegib, Sonidegib, Glasdegib | BCC, medulloblastoma, pancreatic, lung | Phase II–III | [44, 48, 60–63] |

| GLI Inhibitors | GANT61, Arsenic Trioxide | Medulloblastoma, pancreatic cancer | Preclinical | ||

| Antibody Therapies | 5E1, GDC-0449 | Various tumors | Preclinical | ||

| PI3K/AKT/mTOR | PI3K Inhibitors | Idelalisib, Copanlisib, Buparlisib | Various cancers | Phase III | [65] |

| AKT Inhibitors | MK-2206, Perifosine, Ipatasertib | Breast, prostate, head & neck cancers | Ongoing trials | [66] | |

| mTOR Inhibitors | Everolimus, Temsirolimus, Rapamycin | Breast, colorectal, hepatocellular carcinoma | Phase III | [67, 68] | |

| Dual PI3K/mTOR Inhibitors | Palbociclib, Ribociclib, Abemaciclib | Various cancers | Clinical trials | [68] | |

| Metabolic Regulators | Matcha tea, Folate supplementation | Breast, lung cancer | Preclinical | [48] | |

| JAK/STAT | JAK Inhibitors | Ruxolitinib, Tofacitinib | Myeloproliferative neoplasms, other cancers | Phase III | [65] |

| STAT Inhibitors | Stattic, Cucurbitacin I | Various cancers | Preclinical | [44] | |

| Cytokine Receptor Blockers | Tocilizumab, Oclacitinib | Breast, HCC, colorectal, head & neck cancers | Ongoing trials | [66] | |

| MicroRNA Regulators | miR-30, miR-93 | Breast, glioma, lung | Preclinical | [67] | |

| Endogenous Inhibitors | Von Hippel-Lindau | Glioma and lung cancer stem cells | Preclinical | [48] |

|

Figure 1: Global Distribution of Cancer Mortality and Incidence by Region, Sourced from CANCER TODAY (https://gco.iarc.fr/today/), providing comprehensive data on the global cancer burden in 2022 from GLOBOCAN estimates for year 2022 across 185 countries, covering 36 cancer types by sex and age group.Click here to view Figure |

|

Figure 2: Global Cancer Incidence Top 10 in male and female, Sourced from CANCER TODAY (https://gco.iarc. fr/today/), providing comprehensive data on the global cancer burden in 2022 from GLOBOCAN estimates for year 2022 across 185 countries, covering 36 cancer types by sex and age group.Click here to view Figure |

|

Figure 3: Cancer Incidence Top 10 in male and female in Asia, Sourced from CANCER TODAY (https://gco.iarc .fr/today/), presenting detailed insights into cancer prevalence in 2022 based on GLOBOCAN estimates for year 2022 across 185 countries, covering 36 cancer types by sex and age group.Click here to view Figure |

|

Figure 4: Cancer Incidence Top 10 in male and female in India, Sourced from CANCER TODAY (https://gco.iarc. fr/today/), presenting detailed insights into cancer prevalence in 2022 based on GLOBOCAN estimates for year 2022 across 185 countries, covering 36 cancer types by sex and age group.Click here to view Figure |

Conclusion

Targeted cancer therapy has emerged as a transformative approach in oncology, built upon our growing understanding of dysregulated signaling networks that sustain tumor development and progression. This review has explored five critical oncogenic pathways—Wnt/β-catenin, Notch, Hedgehog, PI3K/AKT/mTOR, and JAK/STAT—and their relevance to the hallmarks of cancer. While substantial progress has been made in identifying actionable targets within these pathways, translating this knowledge into lasting therapeutic outcomes remains a formidable challenge.

Each of these pathways plays a multifaceted role in tumor biology, from driving proliferation and evading apoptosis to fostering immune escape and therapeutic resistance. Although targeted agents—such as SMO inhibitors for Hedgehog, mTOR inhibitors for PI3K/AKT/mTOR, and JAK inhibitors in hematological malignancies—have achieved regulatory approval, their efficacy in solid tumors is often limited by pathway redundancy, compensatory signaling, and intratumoral heterogeneity. Additionally, many inhibitors suffer from off-target toxicity or lose effectiveness due to the emergence of resistance mechanisms.44,48,54,64

Importantly, crosstalk between these signaling cascades exacerbates the complexity of targeting a single pathway in isolation. For example, inhibition of PI3K may inadvertently activate MAPK or JAK/STAT signaling, diminishing the overall therapeutic benefit. Therefore, future strategies must focus on rational combination therapies that can simultaneously target multiple oncogenic drivers or circumvent adaptive resistance. These may include combinations with immunotherapies, epigenetic modulators, or cell cycle checkpoint inhibitors.48,54,64

Another key challenge lies in patient stratification. The success of targeted therapy hinges on identifying individuals most likely to respond to specific interventions. The development and integration of predictive biomarkers, genomic profiling, and transcriptomic data are critical to implementing personalized medicine. Technologies such as single-cell sequencing, CRISPR-based functional genomics is accelerating this process and can help uncover novel vulnerabilities within these pathways.50

Furthermore, the tumor microenvironment (TME) presents both obstacles and opportunities. Many of the pathways discussed are influenced by or contribute to an immunosuppressive TME. Therapeutic interventions that modulate the TME—either by reprogramming stromal cells or enhancing immune infiltration—could synergize with pathway inhibitors to improve clinical responses.44,65

In conclusion, while our understanding of cancer biology has advanced considerably, the path toward durable, pathway-targeted cancer therapies requires continued innovation and refinement. A systems-level approach, integrating multi-omics data, machine learning, and patient-specific modeling, holds promise in navigating the complexity of cancer signaling. This review underscores the importance of pathway-centric therapeutic design and advocates for a future where cancer treatment is more precise, dynamic, and adaptive to the evolving nature of the disease.

Acknowledgement

The authors are thankful to the University Institute of Engineering and Technology, Kurukshetra University, Kurukshetra, Haryana for providing their facilities for this study.

Funding Sources

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

This statement does not apply to this article.

Ethics Statement

This research did not involve human participants, animal subjects, or any material that requires ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not involve human participants, and therefore, informed consent was not required.

Clinical Trial Registration

This research does not involve any clinical trials.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

Proper citation has been added for the Figures reproduced (Sourced from CANCER TODAY: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/).

Author Contributions

Ritika Gera: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Data collection.

Rajesh Kumar: Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Kamaljit Panchal: Reviewing.

Vikas Sharma: Reviewing.

Ramika Garg: Reviewing.

References

- Cooper GM. The development and causes of cancer. In: The Cell: A Molecular Approach. 2nd ed. Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates; 2000. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK9963/

- Harika V, Vanitha K, Harika Y, Yamini J, Sravani T. Diagnosis of cancer. Int J Res Pharm Chem. 2015;5(2):299-306.

- Yu Z, Gao L, Chen K, et al. Nanoparticles: a new approach to upgrade cancer diagnosis and treatment. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2021;16(1):88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-021-03489-z

CrossRef - Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7-30. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21590

CrossRef - Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, et al. Cancer statistics for the year 2020: an overview. Int J Cancer. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.33588

CrossRef - Sankaranarayanan R, Ramadas K, Qiao YL. Managing the changing burden of cancer in Asia. BMC Med. 2014;12:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-12-3

CrossRef - Chanu MT, Singh AS. Cancer disease and its understanding from the ancient knowledge to the modern concept. World J Adv Res Rev. 2022;15:169-176. https://doi.org/10.30574/ wjarr.2022.15.2.0809

CrossRef - Farshi E. Comprehensive overview of 31 types of cancer: incidence, categories, treatment options, and survival rates. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/ 377327986

CrossRef - Bray F, Laversanne M, Weiderpass E, Soerjomataram I. The ever-increasing importance of cancer as a leading cause of premature death worldwide. Cancer. 2021;127:3029-3030. https://doi.org/10.1002/ cncr.33587

CrossRef - Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024. https://doi.org/ 10.3322/ caac.21834

CrossRef - Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, et al. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2024. https://gco.iarc.who.int/today. Accessed May 30, 2024.

CrossRef - Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646-674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013

CrossRef - Hanahan D. Hallmarks of cancer: new dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022;12:31-46. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-1059

CrossRef - Nia HT, Munn LL, Jain RK. Physical traits of cancer. Science. 2020;370:eaaz0868. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaz0868

CrossRef - Werner H, LeRoith D. Hallmarks of cancer: the insulin-like growth factors perspective. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1055589. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.1055589

CrossRef - You M, Xie Z, Zhang N, et al. Signaling pathways in cancer metabolism: mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):196. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-023-01442-3

CrossRef - Kanwal R, Gupta S. Epigenetic modifications in cancer. Clin Genet. 2012;81(3):303-311. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01809.x

CrossRef - Min HY, Lee HY. Molecular targeted therapy for anticancer treatment. Exp Mol Med. 2022;54(12):1670-1694. https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-022-00864-3

CrossRef - Lee EY, Muller WJ. Oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2(10):a003236. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a003236

CrossRef - Castellani G, Buccarelli M, Arasi MB, et al. BRAF mutations in melanoma: biological aspects, therapeutic implications, and circulating biomarkers. Cancers. 2023;15(16):4026. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15164026

CrossRef - Johnson DB, Puzanov I. Treatment of NRAS-mutant melanoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2015;16(4):15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11864-015-0330-z

CrossRef - Hernández Borrero LJ, El-Deiry WS. Tumor suppressor p53: biology, signaling pathways, and therapeutic targeting. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2021;1876(1):188556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2021.188556

CrossRef - Zeng Z, Fu M, Hu Y, et al. Regulation and signaling pathways in cancer stem cells: implications for targeted therapy for cancer. Mol Cancer. 2023;22:172. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-023-01877-w

CrossRef - Weinberg RA. How cancer arises. Sci Am. 1996;275(3):62-70. https://doi.org/10.1038/ scientificamerican0996-62

CrossRef - Dhomen N, Marais R. BRAF signaling and targeted therapies in melanoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2009;23(3):529-ix. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hoc.2009.04.001

CrossRef - Gysin S, Salt M, Young A, McCormick F. Therapeutic strategies for targeting ras proteins. Genes Cancer. 2011;2(3):359-372. https://doi.org/10.1177/1947601911412376

CrossRef - Jia P, Zhao Z. Characterization of tumor-suppressor gene inactivation events in 33 cancer types. Cell Rep. 2019;26:496-506.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2018.12.066

CrossRef - Furukawa H, Makino T, Yamasaki M, et al. PRIMA-1 induces p53-mediated apoptosis by upregulating Noxa in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma with TP53 missense mutation. Cancer Sci. 2018;109:412-421. https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.13454

CrossRef - Yang X, Wu H. RAS signaling in carcinogenesis, cancer therapy, and resistance mechanisms. J Hematol Oncol. 2024;17:108. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-024-01631-9

CrossRef - Bowden GT, Schneider B, Domann R, Kulesz-Martin M. Oncogene activation and tumor suppressor gene inactivation during multistage mouse skin carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 1994;54:1882s-1885s.

CrossRef - Meling GI, Lothe RA, Børresen AL, et al. The TP53 tumour suppressor gene in colorectal carcinomas. I. Genetic alterations on chromosome 17. Br J Cancer. 1993;67:88-92. https://doi.org/10.1038/ bjc.1993.14

CrossRef - Payne SR, Kemp CJ. Tumor suppressor genetics. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:2031-2045. https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/bgi223

CrossRef - Haque S, Morris JC. Transforming growth factor-β: A therapeutic target for cancer. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(8):1741-1750. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2017.1327107

CrossRef - Feng R, Yin Y, Wei Y, et al. Mutant p53 activates hnRNPA2B1-AGAP1-mediated exosome formation to promote esophageal squamous cell carcinoma progression. Cancer Lett. 2023;562:216154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2023.216154

CrossRef - Goel S, Bergholz JS, Zhao JJ. Targeting CDK4 and CDK6 in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2022;22(6):356-372. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-022-00456-3

CrossRef - Visconti R, Della Monica R, Grieco D. Cell cycle checkpoint in cancer: a therapeutically targetable double-edged sword. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2016;35(1):153. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-016-0433-9

CrossRef - Kastan MB, Bartek J. Cell-cycle checkpoints and cancer. Nature. 2004;432(7015):316–323. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03097

CrossRef - Finn RS, Aleshin A, Slamon DJ. Targeting the cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK) 4/6 in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res. 2016;18(1):17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-015-0661-5

CrossRef - Yap TA, Omlin A, de Bono JS. Development of therapeutic combinations targeting major cancer signaling pathways. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(12):1592–1605. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.37.6418

CrossRef - Sarkar S, Horn G, Moulton K, et al. Cancer development, progression, and therapy: an epigenetic overview. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(10):21087–21113. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms141021087

CrossRef - Yip HYK, Papa A. Signaling pathways in cancer: therapeutic targets, combinatorial treatments, and new developments. Cells. 2021;10(3):659. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10030659

CrossRef - Chaffey N, Alberts B, Johnson A, et al. Molecular biology of the cell. 4th edn. Ann Bot. 2003;91(3):401. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcg023

CrossRef - Talukdar J, Srivastava TP, Sahoo OS, et al. Cancer stem cells: Signaling pathways and therapeutic targeting. MedComm-Oncol. 2023;2(4):e62.

CrossRef - Espinosa-Sánchez A, Suárez-Martínez E, Sánchez-Díaz L, Carnero A. Therapeutic targeting of signaling pathways related to cancer stemness. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1533. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.01533

CrossRef - National Cancer Institute. Cancer types. 2021. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/types

- Chen B, Dodge ME, Tang W, et al. Small molecule-mediated disruption of Wnt-dependent signaling in tissue regeneration and cancer. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5(2):100-107. https://doi.org/10.1038/nchembio.137

CrossRef - Clevers H, Loh KM, Nusse R. Stem cell signaling. An integral program for tissue renewal and regeneration: Wnt signaling and stem cell control. Science. 2014;346(6205):1248012. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1248012

CrossRef - Yang L, Shi P, Zhao G, et al. Targeting cancer stem cell pathways for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5(1):8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-020-0110-5

CrossRef - Zhang Y, Wang X. Targeting the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13(1):165. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-020-00990-3

CrossRef - Gonsalves FC, Klein K, Carson BB, et al. An RNAi-based chemical genetic screen identifies three small-molecule inhibitors of the Wnt/wingless signaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(15):5954-5963. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1017496108

CrossRef - Anastas JN, Moon RT. WNT signalling pathways as therapeutic targets in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(1):11-26. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3419.

CrossRef - MacDonald BT, He X. Frizzled and LRP5/6 receptors for Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4(12):a007880. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a007880

CrossRef - Holland JD, Klaus A, Garratt AN, Birchmeier W. Wnt signaling in stem and cancer stem cells. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2013;25(2):254-264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceb.2013.01.004

CrossRef - Jung YS, Park JI. Wnt signaling in cancer: therapeutic targeting of Wnt signaling beyond β-catenin and the destruction complex. Exp Mol Med. 2020;52(2):183-191. https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-020-0380-6

CrossRef - Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(21):2018-2028. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1501824.

CrossRef - Ranganathan P, Weaver KL, Capobianco AJ. Notch signalling in solid tumours: a little bit of everything but not all the time. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(5):338-351. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3035

CrossRef - Purow B. Notch inhibition as a promising new approach to cancer therapy. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;727:305-319. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-0899-4_23

CrossRef - Guo H, Lu Y, Wang J, et al. Targeting the Notch signaling pathway in cancer therapeutics. Thorac Cancer. 2014;5(6):473-486. https://doi.org/10.1111/1759-7714.12143

CrossRef - Aster JC, Blacklow SC. Targeting the Notch pathway: twists and turns on the road to rational therapeutics. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(19):2418-2420. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.42.0992

CrossRef - Jiang J, Hui CC. Hedgehog signaling in development and cancer. Dev Cell. 2008;15(6):801-812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2008.11.010

CrossRef - Skoda AM, Simovic D, Karin V, Kardum V, Vranic S, Serman L. The role of the Hedgehog signaling pathway in cancer: a comprehensive review. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2018;18(1):8-20. https://doi.org/10.17305/bjbms.2018.2756

CrossRef - Gupta S, Takebe N, Lorusso P. Targeting the Hedgehog pathway in cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2010;2(4):237-250. https://doi.org/10.1177/1758834010366430

CrossRef - Yauch RL, Gould SE, Scales SJ, et al. A paracrine requirement for hedgehog signalling in cancer. Nature. 2008;455(7211):406-410. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07275

CrossRef - Liu P, Cheng H, Roberts TM, Zhao JJ. Targeting the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8(8):627-644. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd2926

CrossRef - Bournazou E, Bromberg J. Targeting the tumor microenvironment: JAK-STAT3 signaling. JAK-STAT. 2013;2(2):e23828. https://doi.org/10.4161/jkst.23828

CrossRef - Fagard R, Metelev V, Souissi I, Baran-Marszak F. STAT3 inhibitors for cancer therapy: Have all roads been explored?. JAK-STAT. 2013;2(1):e22882. https://doi.org/10.4161/jkst.22882

CrossRef - Qureshy Z, Johnson DE, Grandis JR. Targeting the JAK/STAT pathway in solid tumors. J Cancer Metastasis Treat. 2020;6:27.

CrossRef - Donnell A, Faivre S, Burris HA 3rd, et al. Phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of the oral mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor everolimus in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(10):1588–1595. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2007.14.0988

CrossRef - Janku F, Yap TA, Meric-Bernstam F. Targeting the PI3K pathway in cancer: are we making headway? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15(5):273–291. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2018.28

CrossRef - Saxton RA, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth, metabolism, and disease. Cell. 2017;169(2):361–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2017.03.035

CrossRef

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.