Manuscript accepted on : 03-04-2025

Published online on: 10-06-2025

Plagiarism Check: Yes

Reviewed by: Dr. Moumita Hazra

Second Review by: Dr. Maysloon Hamied

Final Approval by: Dr. Hifzur Siddique

Swapnali Jyotiba Bhagat1* , Vishal Sudam Adak1

, Vishal Sudam Adak1 , Shrikant Ramchandra Borate1

, Shrikant Ramchandra Borate1 , Rajkumar Virbhadrappa Shete1

, Rajkumar Virbhadrappa Shete1 , Deepak Vitthalrao Fajage1

, Deepak Vitthalrao Fajage1 , Shivkumar Manoharrao Sontakke2

, Shivkumar Manoharrao Sontakke2 , Jayshri Anna Tambe3

, Jayshri Anna Tambe3 and Prajakta Anil Kakade2

and Prajakta Anil Kakade2

1Department of Pharmacology, Rajgad Dnyanpeeth’s College of Pharmacy, Bhor, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

2Department of Pharmaceutics, Government College of Pharmacy, Karad, Satara, Maharashtra, India.

3Department of Pharmacology, Dr. D. Y. Patil Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research, Pimpri, Pune , Maharashtra, India.

Corresponding Author E-mail: swapnalibhagat1208@gmail.com

DOI : http://dx.doi.org/10.13005/bbra/3377

ABSTRACT: The fourth most common cause of disease burden worldwide is epilepsy. A chronic neurological disorder marked by frequent, unprovoked seizures brought on by aberrant brain electrical activity. It affects more than 60 million people globally, has a significant detrimental impact on patients' life quality, and is linked to comorbid conditions like anxiety, depression, and cognitive impairment. About 30% of patients have drug-resistant epilepsy, which raises death rates and emphasises the need for alternative therapeutic approaches even though there are more than 30 antiepileptic medications (AEDs) that have received USFDA approval. The pathophysiology of epilepsy is examined in this study, with particular attention paid to ion channel dysregulation and neurotransmitter abnormalities, such as glutamate-mediated pathways and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA). Along with the pharmacological targets and MOA of current AEDs, classification of epilepsy and seizures—including generalised, partial, and status epilepticus forms—is covered. The potential of plant-based phytochemicals as multitarget therapeutic agents is investigated in light of the shortcomings of existing treatments. Preclinical research shows how well these substances work to change important biochemical pathways and receptors, highlighting their potential as supplements or substitutes for traditional AEDs. Clarifying their modes of action, optimizing dosage, and ensuring safety still present difficulties. Given that 80% of epilepsy occurrences occur in low-income areas with limited access to effective treatments, this review highlights the critical need for accessible and reasonably priced therapeutics. Research on phytochemicals offers a viable way to fill up these gaps and could revolutionise the way epilepsy is managed globally. Alkaloids, Phenolics, Terpenoids, Flavonoids like quercetin, kaempferol, and luteolin have shown promise in reducing seizure frequency and protecting against neuronal damage.

KEYWORDS: Antiepileptic drugs; Epilepsy; Pathophysiology; Phytochemicals; Seizure Management

Download this article as:| Copy the following to cite this article: Bhagat S. J, Adak V. S, Borate S. R, Shete R. V, Fajage D. V, Sontakke S. M, Tambe J. A, Kakade P. A. Epilepsy: Insights into Pathophysiology, Therapeutic Approaches, and the Emerging Role of Phytochemicals. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(2). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Bhagat S. J, Adak V. S, Borate S. R, Shete R. V, Fajage D. V, Sontakke S. M, Tambe J. A, Kakade P. A. Epilepsy: Insights into Pathophysiology, Therapeutic Approaches, and the Emerging Role of Phytochemicals. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(2). Available from: https://bit.ly/43QiwRo |

Introduction

Seizures represent a sudden and transient neurological event characterized by abnormal, excessive electrical activity within a population of central nervous system neurons. This rapid, synchronous firing can arise from various etiologies, including epileptic conditions, systemic metabolic disturbances (e.g., hypoglycaemia, hypercalcemia), intracranial infections, severe systemic infections, or as an adverse effect of certain medications. Epilepsy encompasses a spectrum of chronic neurological disorders defined by the recurrent occurrence of seizures, often accompanied by alterations in consciousness and/or characteristic motor manifestations (convulsions). Autonomic dysfunction may also be observed in some cases.1

Epilepsy is a prevalent and significant neurological disorder, affecting approximately 1% of the global population. A considerable subset of these individuals, around one-third, experience refractory epilepsy, characterized by seizures that are not adequately managed with standard antiepileptic drugs. Notably, the onset of epilepsy occurs in about 75% of cases during childhood, underscoring the increased vulnerability of the developing brain to epileptic events. However, in developed nations, the incidence of childhood epilepsy has declined over the past thirty years, while there has been a corresponding rise in the prevalence among the elderly population.2-5

Epilepsy is a neurological disorder impacting individuals across different age groups, characterized by abnormal electrical activity in parts or throughout the brain. This condition manifests as seizures, which can occur spontaneously and recurrently. Seizures may result from a variety of factors, including stroke, brain tumours, head trauma, or central nervous system infections. It is estimated that approximately fifty million people worldwide are currently living with epilepsy, and this disorder accounts for about one percent of the global disease burden, with higher prevalence in low- and middle-income countries. Despite the availability of numerous pharmacological treatments for epilepsy, a significant number of patients remain unresponsive or develop resistance to antiepileptic drugs, making pharmacoresistance a major clinical challenge in the treatment of epilepsy.6-9

Epilepsy is a prevalent, severe, chronic, and potentially life-shortening neurological disorder marked by a continuous predisposition to seizures. It impacts over 60 million people worldwide and is a significant contributor to seizure-related mortality, comorbidities, disabilities, and healthcare costs. Various treatment strategies have been employed to manage epilepsy, and over 30 drugs have received approval from the US FDA. However, approximately 25% of individuals with epilepsy remain resistant to these treatments. Approximately 90% of people in low- and middle-income countries lack access to modern epilepsy medications. In these regions, traditional remedies such as plant extracts have been employed to treat various conditions, including epilepsy. These medicinal plants offer significant therapeutic potential due to their valuable phytochemical content with a range of biomedical applications. Given that epilepsy is a multifactorial disorder, multitarget approaches using plant extracts or isolated phytochemicals are necessary, as they can address multiple pathways simultaneously. Various plant extracts and phytochemicals have demonstrated efficacy in treating epilepsy in different animal models by interacting with diverse receptors, enzymes, and metabolic pathways. These natural compounds hold potential for future use in human epilepsy treatment. However, more research is required to elucidate their precise mechanisms of action, assess toxicity, and determine appropriate dosages to minimize side effects.10-17

Types of epilepsy.1, 18-24

Primarily generalized seizures

Generalized tonic-clonic seizures (Grand mal)

Tonic seizures

Atonic seizures

Absence seizures (Petit mal)

Myoclonic seizures

Partial seizures (Focal or local seizures)

Simple partial seizures

Complex partial seizures

Secondary generalized seizures

Primarily generalized seizures

Generalized tonic-clonic seizures (Grand mal epilepsy)

These are also called as grand mal epilepsy / major epilepsy. One of the serious type of convulsions which consist of maximum tonic spasms of all body muscles then instantaneous jerking moments followed by central depression. Tonic-clonic seizures cause instant loss in awareness (consciousness) without any signs then tonic and then clonic convulsions. Drowsiness, sleep and headache are the minor symptoms of the attack. Convulsive moments also include frothing, tongue biting and urinary incontinence. When the term “epileptic fit” is used informally, it usually refers to this kind of seizure.

Tonic seizures

Tonic seizures, also known as opisthotonus, cause significant autonomic symptoms and unconsciousness. Without the clonic phase, it resembles tonic-clonic seizures.

Atonic seizures

Head slumping, falling, and/or loss of postural tone are the hallmarks of atonic seizures. Loss of muscular tone during atonic seizures results in the person falling to the ground. These are commonly referred to as “drop attacks,” although they should be differentiated from similar-looking events that can happen in people with cataplexy or narcolepsy.

Absence seizures (Petit mal)

An interruption of consciousness known as an absence seizure, occurs when the person having the seizure appears vacant and unresponsive for a brief moment (often up to 30 seconds). There may be a slight twitching of muscles.

Typical absence seizures

Atypical absence seizures

Myoclonic seizures

These are clonic jerks associated with short bursting of many spikes in electroencephalogram. Muscles or muscle groups may jerk during myoclonic seizures, which are characterized by a very short (<0.1 second) contraction of the muscles.

Partial seizures

These are also called as focal seizures / local seizures. There are two types of partial seizures i.e. simple partial seizures and complex partial seizures.

Simple partial seizures

There are several ways that simple partial seizures might appear without impairing consciousness. Depending on the precise cortical area generating the aberrant discharge, they may include unique and localized sensory problems (Jacksonian sensory epilepsy), convulsions restricted to a single limb or muscle group (Jacksonian motor epilepsy), and other limited signs and symptoms. Simple seizures may result in sensory abnormalities or other symptoms, but they do not disrupt consciousness.

Complex partial seizures

These attacks cause disorientation and awareness impairment. In addition to a variety of clinical symptoms, such as odd worldwide EEG activity during the seizure, they frequently show signs of localized abnormalities in the front temporal lobe during the inter-seizure phase. Complex seizures cause varied degrees of awareness disruption. This does not imply that the individual having this kind of seizure will faint or become unconscious.

Secondary generalized seizures

These seizures begin as simple partial seizures, which progress to become generalized seizures. Todd’s paralysis, a postictal neurological impairment, may occur after such a seizure. Jacksonian seizures occur when the motor phenomena spread in an orderly fashion.

Status epilepticus (SE)

SE is characterized by repeated seizures of any kind or prolonged seizures (lasting more than five to ten minutes) with no recovery in between bouts. When tonic-clonic seizures develop into the SE, which might be lethal, a medical emergency arises. The aforementioned explanation pertains to a category called “seizures.” However, the classification of “epilepsies” also has to consider the prognosis, responsiveness to treatment, age of onset, hereditary variables, EEG abnormalities, concomitant neurologic deficits, and imaging results. When choosing a medication and assessing prognosis, it may be more beneficial to define a particular epilepsy syndrome rather than focusing solely on seizure characteristics. Approximately 10% of people with actual seizures have several EEG examinations that show no abnormalities. Therefore, in a person with a definitive clinical picture, there is no way to rule out a seizure illness with a normal EEG.

Classification of anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs).18,25-27

Classification according to chemical Nature

Barbiturate: Phenobarbitone.

Hydantoins: Phenytoin, Mephenytoin, Phenyl ethyl hydantoin.

Oxazolidinediones: Trimethadone, Paramethadione.

Phenacemide: Phenacemide, Phenyl ethyl acetyl urea.

Benzodiazepines: Nitrazepam, Clonazepam.

Iminostilbenes: Carbamazepine.

Miscellaneous: Sodium Valproate (Valproic acid)

Classification according to Mode of Action:

Modulation of Ion Channels: Phenytoin, Carbamazepine, Lamotrigine, Oxcarbazepine, Ethosuximide, Zonisamide.

Potentiation of γ-amino Butyric Acid: Phenobarbital, Benzodiazepines, Vigabatrin, Tiagabine.

Drugs with multiple mechanism of action: Sodium Valproate, Gabapentin, Felbamate, Topiramate.

Drugs with unknown mechanism of action: Levetiracetam.

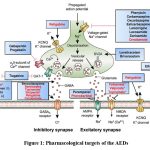

Pharmacological targets of AEDs.18,28-35

|

Figure 1: Pharmacological targets of the AEDsClick here to view Figure |

Voltage dependent ion channels are targets for many antiepileptic drugs. These are Na+, Ca+ and K+.

Ion Channels

Na+ channels:

These ion channels regulate movement of cations across internal to external cell membranes. The multi-subunit structure of neuronal sodium channel creates voltage-gated, Na+-selective pore across the plasma membrane. Conductance via the intrinsic pore is controlled by conformational changes in the protein structure in response of variations in the membranous potential. Primary structural element of the sodium channels of nervous system is subunit-A. Another two subunits like subunit-β1 and subunit-β2, form associations with α-subunit in the mammalian brain. Subunit- β1 and subunit-β2 are not necessary for the sodium channel activity. The majority of Na+ channels are in a closed, resting state at typical membrane potentials. Ion flux is facilitated by the channel’s activation upon depolarization. The Na+ channel then goes into an inactivated state from which it is difficult to restart. The channel quickly returns to a permanent state upon repolarization of the neuronal membrane, from which it can react to further depolarizations.

Ca2+

These are analogue of voltage gated sodium channels. The analogue of α1-subunit of sodium channel is subunit- α of Ca2+ channel. This adds voltage dependency and creates the Ca2 + sensitive channel pore. Ca2+ channels are classified as either low threshold or high threshold based on their membrane potential. It is believed that the minimal-threshold T-type calcium channel, which mostly found in relay neurons in the thalamocortical region, is responsible for the rhythmic 3-Hz spike-and-wave discharge that is characteristic of generalized absence seizures. Based on their pharmacological characteristics, high-threshold Ca2+ channels divided in type P-, R-, Q-, N-, and type L-. All channels are found on cell bodies, nerve terminals and dendrites throughout CNS. Regulation of neurotransmitter release at synapse has been linked to the P-, Q- and N-type. In order to contribute to anti-epileptic medications, many AEDs work by inhibiting voltage-sensitive Ca2+ channels.

K + channels

In the large complexes of protein, K+ channels are in the form of tetramer, and their monomers share structural and genetic similarities with the Ca+ and Na+ channels via the α1 and α1 subunits, respectively. The excitation involves K+ channels. They are in charge of the Na+ channel’s plasma membrane repolarization. Direct voltage-dependent K+ channel activation inhibits action potential firing and hyperpolarizes the neuronal membrane. K+ channel blockers cause seizures, while potassium channel facilitator shows antiepileptic benefits in several experimental animal models. AED development in the future may focus on acceleration of potassium ion channel currents.

γ- Aminobutyric acid-mediated inhibition

GABA, central nervous system’s main inhibitory neurotransmitter.

It is well known that seizures are triggered by impairment of GABA function, while stimulation has an anticonvulsant effect. The enzyme glutamic acid decarboxylase is responsible for the synthesis of GABA in GABAergic neurons. GABA is crucial for regulating both the excitatory output from the cortex and glutamate-mediated excitatory activity within it. GABA receptors come in two subtypes, known as GABAA and GABAB, as well as the recently identified GABAC. Fast neurotransmission is facilitated by GABAA receptors, which are mostly found on postsynaptic membranes. The ligand-gated ion channel superfamily includes it and causes neuronal hyperpolarization in response of binding of GABA by conductance of chloride ions. K+ conductance rises when G-protein coupled receptors like GABAB gets activated. The transmitter gated channel, which forms the pore from which Cl– ions comes in the neuron of post synapse, after GABAA receptor occupation, is made up of five membrane-spanning subunits, including the GABAA receptor. Four different transmembrane spanning domains make up each of the five subunits. α, β, γ, δ, and ρ are the thesis subunits that make up the ionophore; each of these subunits, except for δ, has several isomeric forms; 3 y subunits (γ1-γ3), 4 β subunits (β1~β4), and 6 subunits (αl-α6) are present. one subunit of δ, and 2 subunits of ρ i.e. (ρl-ρ2), It appears to be situated in the retina. GABA’s synaptic activity is stopped by GABA transporters found on glial cells and presynaptic nerve terminals. There are about 4 known GABA transporter proteins. These proteins include GAT-1, GAT-2, GAT-3 and BGT-1. Sodium and chloride gradients of transmembrane are necessary for the functions of GABA transporters.

Glutamate (GLUT) Mediated Receptor

The main excitatory neurotransmitter in the neurological system is glutamate. Animal experiences epileptic seizures when they receive glutamate’s focal injections. Several epilepsy disorders and animal seizure models exhibit aberrant glut receptor characteristics or over-activation of glutamatergic transmission. Numerous receptors are affected by glutamate’s pharmacological actions. Glutamate is changed into glutamine by glial cells using the enzyme glutamine synthetase. making glial glutamate uptake crucial. The cycle is then completed when glutamine is delivered to glutamatergic neurons. Ionotropic receptors of glutamate, like GABA receptors, made up of the several subunit combinations which forms arrays of tetrameric and pentameric forms. Three separate subtypes are distinguished among them: N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-isoxazole-4-propionic acid (AMPA) and kainite. These subtypes produce ion channels that are ligand-gated that permit the passage of sodium also contain Ca2+ ions based on the subtype and subunit composition. Glycine’s role as a co-agonist further distinguishes NMDA receptor. Glutamate receptor subtypes AMPA and kainate are linked to rapid excitatory transmission of neurons. While another subtype i.e. NMDA which is dormant at the resting membrane potential which activated by extended depolarization.

Screening models of epilepsy.36,37

In vivo methods

Maximal electroshock induced convulsions in mice.38-40

The main aim of the electroshock method in animals used is to identify substances that are useful in treating grand mal epilepsy. Anti-epileptic medications and other centrally active medications block the electric impulses that cause tonic hindlimb extensions.

Procedure

NMRI mice (Male) weighing 18–30 gram are utilized in groups of 6–10. The test begins thirty minutes after i.p. injection / sixty minutes Upon oral administration of vehicle or test chemical. The stimuli are delivered using a device that has electrodes in the cornea or ears (Woodbury and Davenport 1952). The device determines the stimulus’s intensity; for example, 12 mA and 50 Hz for 0.2 s have been employed. All mice given the vehicle exhibit the distinctive extensor tonus under these circumstances.

Evaluation

For two minutes, the animals are closely watched. The lack of the hindleg extensor tonic convulsion is the condition for affirmation. The percentage of seizures that are inhibited in comparison to controls is computed. Probit analysis is used to get ED50 values and the 95% Confidence interval using different doses.

Pentylenetetrazol (Metrazol) induced convulsions.39-44

The main aim of this test is to assess anti-epileptic medications. Anxiolytic medications can likewise to stop or counteract convulsions brought on by Metrazol.

Procedure

Both sexes of mice having weight between 18 and 22 grams are employed. Groups of ten mice receive oral, intraperitoneal, or sc. injections of the test substance or reference medication. A control group of ten mice is used. 30 minutes following intraperitoneal injection, 15 minutes following sc. injection, or 60 minutes following oral delivery Metrazol (60 mg/kg) is administered subcutaneously. Every animal is kept in a separate plastic cage for a one-hour observation period. Tonic-clonic convulsions and seizures are documented. The control group’s animals must exhibit convulsions in at least 80% of cases.

Evaluation

The percentage of afflicted animals in the control group is used to determine the quantity of animals in the treated groups that are protected. It is possible to compute ED50 values. Additionally, it is possible to measure the interval between the metrazol injection and the onset of seizures. The onset delay is computed compared to the control group.

Strychnine-induced convulsions.45,46

Strychnine causes convulsions via interfering with glycine-mediated postsynaptic inhibition. Strychnine works as a competitive, selective antagonist to prevent glycine from inhibiting any glycine receptor. Glycine is crucial inhibitory transmitter to interneurons and moto-neurons in spinal cord. Glycine also mediates postsynaptic inhibition which is strychnine-sensitive in the higher centres of central nervous system. It has been demonstrated that compounds that counteract strychnine’s effects have anxiolytic effects.

Procedure

10 mice of each sex with wt. about 18 to 22 grams, which utilized in groups. Test substance / std one (such as 5 mg per kg of diazepam) is administered orally to them. After an hour, the mice get an i.p. injection of strychnine nitrate at dose 2 mg per kg. A period of 11 is used to record the duration till death and tonic extensor convulsions. Eighty percent of the controls experience convulsions when given this dosage of strychnine.

Evaluation

Using several doses and a 100% control percentage, ED50 values are computed. The duration between treatment and strychnine injection for time response curves ranges from 30 to 120 minutes.

Isoniazid-induced convulsions.47,48

Patients with seizure disorders may experience convulsions as a result of taking isoniazid. The substance is thought to be an inhibitor of GABA production. Mice experience clonic-tonic convulsions, which anxiolytic medications counteract.

Procedure

The test substance or std one (e.g., diazepam 10 mg per kg intraperitoneally) will administer orally or i.p. to ten either sex mice having weight between 18-22 grams. The controls only receive the vehicle. Mice get a s.c. injection of 300 mg per kg INH thirty min after intraperitoneal or sixty min after postoperative therapy. Death, tonic seizures, and clonic seizures are noted throughout the course of the following 120 minutes.

Evaluation

The control group is assumed to have a 100% chance of seizures or death. The percentage of controls is used to determine how much these effects are suppressed in the treated groups. Values for ED50 are computed.

Picrotoxin-induced convulsions.49

CNS-active substances are further assessed by inducing convulsions with picrotoxin. It is believed that picrotoxin is a GABA-antagonist that alters GABA receptor complex’s Cl– ion channel activity.

Procedure

Test substance or std one (example ten mg per kg diazepam intraperitoneal) is administered orally or intraperitoneally (i.p.) to 10 mice of either sex having wt. between 18-22 grams. Animals get an injection of 3.5 mg per kg subcutaneous picrotoxin 30 minutes after intraperitoneal treatment or sixty minutes after oral delivery. Over the next 30 minutes, they are monitored for the symptoms listed: tonic seizures, clonic seizures and death. Seizures starting time and death time are noted.

Evaluation

The animals are given the medication 30, 60, or 120 minutes before picrotoxin in order to obtain time-response curves. % inhibition in relation to the vehicle control is how protection is expressed. The peak time of pharmacological activity is defined as the time period having the highest percent inhibition. When calculating ED values, the control group’s seizure percentage is set at 100%.

Bicuculline test in rats.50

Bicuculline, a GAGA-antagonist, can cause seizures, while well-known anti-epileptic medications counteract them.

Procedure

Bicuculline at a dose of one milligram per kilogram is administered intravenous to Sprague-Dawley rats (females). Within 30 seconds of injection, all treated rats experience a tonic convulsion at this dosage. The test chemicals are taken orally one or two hours prior to the injection of bicuculline. It is possible to get dose-response curves.

Evaluation

The % of animals that are secured is assessed. Probit analysis is used to determine ED-values and 95% confidence limits.

4-aminopyridine-induced seizures in mice.51

4-aminopyridine, antagonist of K+ channel, causing convulsions in both humans and animals. The medication passes through the blood-brain barrier with ease and is thought to increase both evoked and spontaneous neurotransmitter release, which in turn causes seizure activity. 4-aminopyridine facilitates both inhibitory and excitatory transmission at synapse; nevertheless, non-NMDA type excitatory amino acid receptors are primarily responsible for the drug’s epileptiform action. When 4-aminopyridine is given parenterally to mice, it causes clonic-tonic seizures and death.

Procedure

NIH Swiss mice (Male) with weight 25 to 30 grams are let to become accustomed to open access to water and food for a twenty-four hrs duration pre-testing. 15 minutes before the intraperitoneal injection of 4-aminopyridine at dose of 13.3 milligram per kilogram. Test medicines are given in different doses. Only typical behavioural symptoms, including hyperreactivity, shaking, intermittent hindlimb/forelimb clonus then tonic seizures, opisthotonus, hindlimb extension and death are seen in controls treated with 4-aminopyridine. At the LD97, the average latency to death is roughly ten minutes. Each dose is given to eight mice group.

Evaluation

ED50 values are determined using the proportion of safeguarded animals for every dosage. Broad-spectrum anticonvulsants like phenobarbital and valproate, as well as phenytoin-related anticonvulsants like carbamazepine, are helpful. In contrast, GABA-enhancers like diazepam, CA2+ channel antagonists like nimodipine and a few of NMDA antagonists are not.

Epilepsy induced by focal lesions.52

epilepsy may be caused in animals by intrahippocampal injections of toxic substances or certain brain injuries. Rats given intrahippocampal kainic acid injections had their long-term effects examined by Cavalheiro (1982).

Procedure

A stereotactic setup is used to anesthetize adult Wistar rats (Male) using a chloral hydrate/nembutal mixture. A burr hole into the calvarium is used to implant a 0.3 mm cannula for injections. Hippocampal injection coordinates are derived from a stereo-tactic map, such as Albe-Fessard (1971). In a volume of 0.2 µl, kainic acid is dissolved in the fake serum and administered into different doses (0.1-3.0 µg) over a 3-minute period. For recording, 100 µm bipolar twisted electrodes are stereotaxically placed and cemented to the skull with dental acrylic cement. Two sites for depth recording are the dorsal hippocampus and the amygdala ipsilateral to the injected side. Jeweler’s screws are used to orient surface electrodes across the occipital brain. For grounding, an additional screw serves as an indifferent electrode in the frontal sinus. EEG polygraph records the signals.

Evaluation

Both with and without pharmacological treatment, while the acute phase and the chronic phase (up to two months). EEG recordings and convulsive seizure observations and made.

Genetic animal models of epilepsy.36

Dogs, rats, and mice are among the animal species that exhibit convulsions and spontaneous repeated jerky moments. Double-mutant spontaneous epileptic rats that have both absence-like and tonic seizures were described by Serikawa and Yamada (1986).

Procedure

The tremor heterozygous rat (m/+) and the zitter homozygous rat (zi/zi) from a Sprague-Dawley colony are mated to produce spontaneous epileptic rats. Every week, two hours of the spontaneous epileptic rats’ behaviour are captured on videotapes. When no outside stimuli are present, the incidence of tonic seizures and frantic hopping is seen. The hippocampus and left frontal cortex are permanently implanted with monopolar stainless-steel electrodes and silver ball-tipped electrodes under anaesthesia. The frontal skull is exposed to an indifferent electrode. The EEG measures the duration of each seizure and the frequency of tonic convulsions and absence-like seizures. To produce regular tonic convulsions, a gentle tactile stimulus is applied to the animal’s back every 2.5 minutes. I.P. or oral administration of compounds.

Evaluation

Every five minutes before and after the drug injection, the number of seizures and their durations are recorded, and the sum of the convulsions’ durations (number into duration) computed. Values both prior to and following drug administration are compared as a percentage.

Kindled rat seizure model.53

Goddard (1969) were the first to describe kindling, which is caused by repeated electrical stimulation of specific brain areas that causes sub-convulsions. Local after-discharge is initially linked to modest behavioural symptoms; however, generalized convulsions are likely to arise as electrical activity spreads with sustained stimulation. Despite the incomplete understanding of the pathophysiology of kindling seizures, it is a valuable way to examining effectiveness of antiepileptic medications.

Procedure

The Sprague-Dawley rats utilized are adult females weighing between 270 and 400 g. Pellegrino (1979) used the following coordinates to implant an electrode into the right side of rats’ amygdala: horizontal, 2.5, lateral, -4.7; and frontal, 7.0. Before beginning Brain electrical stimulation, a minimum one week must pass. once each rat’s discharge threshold has been established. Increased stimuli following discharges are used to measure seizure stage, duration, and amplitude of behavioural seizures.

Phytochemicals responsible for Anticonvulsant Activity.54-60

Flavonoids

These polyphenolic compounds, found in fruits, vegetables, and herbs, have demonstrated antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective properties. Flavonoids like quercetin, kaempferol, and luteolin have shown promise in reducing seizure frequency and protecting against neuronal damage.

Terpenoids

These are a large and diverse group of naturally occurring compounds found in essential oils of various plants. Linalool, for instance, found in lavender, has been studied for its sedative and anti-seizure properties.

Alkaloids

Plant-derived alkaloids such as pilocarpine (from Pilocarpus microphyllus) and corydine (from Corydalis species) have been found to exhibit anticonvulsant activity in animal models.

Phenolic Acids

Compounds like rosmarinic acid from rosemary have been researched for their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, which could contribute to their anticonvulsant potential.

Cannabinoids

These are compounds found in the cannabis plant, such as CBD (cannabidiol), which has shown anticonvulsant effects, particularly in drug-resistant forms of epilepsy like Dravet syndrome.

Conclusion

Epilepsy continues to be a major worldwide health issue that impacts millions of people and presents complex challenges in its management. Despite advances in pharmacotherapy. substantial proportion of patients experience drug-resistant epilepsy, emphasizing the urgent need for novel and effective treatment strategies. The pathophysiology of epilepsy, rooted in aberrant electrical activity of the brain, involves dysregulation of ion channels and neurotransmitter systems such as GABA and glutamate pathways. These insights have guided the development of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), which primarily target these mechanisms. However, the limitations of current AEDs, including side effects, high costs, and limited accessibility in low-income regions, necessitate the exploration of alternative therapeutic options.

Phytochemicals, derived from natural sources, offer a promising multitarget approach to epilepsy treatment. Preclinical studies highlight their ability to alter different pathways that are engaged in seizure genesis and propagation. However, further research is needed to clarify their mechanisms of action, determine optimal dosages, and ensure safety in human populations. With 80% of epilepsy cases concentrated in resource-limited settings, phytochemicals may provide cost-effective and accessible solutions. Moving forward, integrating phytochemical research into epilepsy management could transform therapeutic paradigms and improve patient outcomes, particularly in underserved populations, clearing the path for a more comprehensive inclusive method to epilepsy care.

Acknowledgement

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support and resources provided by Rajgad Dnyanpeeth’s College of Pharmacy, Bhor, which were instrumental in the completion of this review article.

Funding Sources

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

This statement does not apply to this article.

Ethics Statement

This research did not involve human participants, animal subjects, or any material that requires ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not involve human participants, and therefore, informed consent was not required.

Clinical Trial Registration

This research does not involve any clinical trials.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

Not Applicable

Author contributions

Swapnali Jyotiba Bhagat: Conceptualization, Literature Review, Review & Editing.

Vishal Sudam Adak: Visualization

Shrikant Ramchandra Borate: Visualization

Rajkumar Virbhadrappa Shete: Supervision

Deepak Vitthalrao Fajage: Data Curation, Review & Editing

Shivkumar Manoharrao Sontakke: Project Administration

Jayshri Anna Tambe: Project Administration

Prajakta Anil Kakade: Project Administration

Reference

- Satoskar, R. S., and Bhandarkar, S. D. (2020). Pharmacology and pharmacotherapeutics. Elsevier India.

- Faheem, M., Ameer, S., Khan, A. W., Haseeb, M., Raza, Q., Shah, F. A., … and Alsiwiehri, N. O. (2022). A comprehensive review on antiepileptic properties of medicinal plants. Arabian Journal of Chemistry, 15(1), 103478.

CrossRef - Chang, H. J., Liao, C. C., Hu, C. J., Shen, W. W., and Chen, T. L. (2013). Psychiatric disorders after epilepsy diagnosis: a population-based retrospective cohort study. PloS one, 8(4), e59999.

CrossRef - Beghi, E. (2020). The epidemiology of epilepsy. Neuroepidemiology, 54(2), 185-191.

CrossRef - Stafstrom, C. E., and Carmant, L. (2015). Seizures and epilepsy: an overview for neuroscientists. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine, 5(6), a022426.

CrossRef - Obese, E., Biney, R. P., Henneh, I. T., Adakudugu, E. A., Anokwah, D., Agyemang, L. S., … and Ameyaw, E. O. (2021). The anticonvulsant effect of hydroethanolic leaf extract of calotropis procera (ait) R. Br.(Apocynaceae). Neural Plasticity, 2021(1), 5566890.

CrossRef - Samokhin, L. (2023). Educational strategies used in paediatric epilepsy: a descriptive literature review.

- Beghi, E., Giussani, G., Nichols, E., Abd-Allah, F., Abdela, J., Abdelalim, A., … and Murray, C. J. (2019). Global, regional, and national burden of epilepsy, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet Neurology, 18(4), 357-375.

CrossRef - Naimo, G. D., Guarnaccia, M., Sprovieri, T., Ungaro, C., Conforti, F. L., Andò, S., and Cavallaro, S. (2019). A systems biology approach for personalized medicine in refractory epilepsy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20(15), 3717.

CrossRef - Waris, A., Ullah, A., Asim, M., Ullah, R., Rajdoula, M. R., Bello, S. T., and Alhumaydhi, F. A. (2024). Phytotherapeutic options for the treatment of epilepsy: pharmacology, targets, and mechanism of action. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 15, 1403232.

CrossRef - Moshé, S. L., Perucca, E., Ryvlin, P., and Tomson, T. (2015). Epilepsy: new advances. The Lancet, 385(9971), 884-898.

CrossRef - Potnis, V. V., Albhar, K. G., Nanaware, P. A., and Pote, V. S. (2020). A review on epilepsy and its management. Journal of Drug Delivery and Therapeutics, 10(3), 273-279.

CrossRef - Falco-Walter, J. (2020, December). Epilepsy—definition, classification, pathophysiology, and epidemiology. In Seminars in neurology(Vol. 40, No. 06, pp. 617-623). Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc.

CrossRef - Maestri, M., Carnicelli, L., Di Coscio, E., Iacopini, E., and Bonanni, E. (2013). Exacerbation of restless legs syndrome presenting as a psychiatric emergency. European Journal of Neurology, 20(6).

CrossRef - Perucca, E. (2021). The pharmacological treatment of epilepsy: recent advances and future perspectives. Acta Epileptologica, 3(1), 22.

CrossRef - Mula, M. (2021). Pharmacological treatment of focal epilepsy in adults: an evidence based approach. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy, 22(3), 317-323.

CrossRef - Berdigaliyev, N., and Aljofan, M. (2020). An overview of drug discovery and development. Future medicinal chemistry, 12(10), 939-947.

CrossRef - Deshmukh, R., Thakur, A. S., and Dewangan, D. (2011). Mechanism of action of anticonvulsant drugs: a review. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research, 2(2), 225.

- Taylor, C. P., Vartanian, M. G., Schwarz, R. D., Rock, D. M., Callahan, M. J., and Davis, M. D. (1990). Pharmacology of Cl‐966: A potent GABA uptake inhibitor, in vitro and in experimental animals. Drug development research, 21(3), 195-215.

CrossRef - Nielsen, E. B., Suzdak, P. D., Andersen, K. E., Knutsen, L. J., Sonnewald, U., and Braestrup, C. (1991). Characterization of tiagabine (NO-328), a new potent and selective GABA uptake inhibitor. European journal of pharmacology, 196(3), 257-266.

CrossRef - Croucher, M. J., Collins, J. F., and Meldrum, B. S. (1982). Anticonvulsant action of excitatory amino acid antagonists. Science, 216(4548), 899-901.

CrossRef - Leander, J. D., Rathbun, R. C., and Zimmerman, D. M. (1988). Anticonvulsant effects of phencyclidine-like drugs: relation to N-methyl-D-aspartic acid antagonism. Brain research, 454(1-2), 368-372.

CrossRef - Meldrum, B. S. (1992). Excitatory amino acids in epilepsy and potential novel therapies. Epilepsy research, 12(2), 189-196.

CrossRef - Kumar, S., Madaan, R., Bansal, G., Jamwal, A., and Sharma, A. (2012). Plants and plant products with potential anticonvulsant activity–a review. Pharmacognosy Communications, 2(1), 3-99.

CrossRef - Tripathi, K. D. (2018). Essentials of medical pharmacology. Jaypee Brothers medical publishers.

- Rang, H. P. (2011). Rang and Dale’s pharmacology. Elsevier Health Sciences. Amsterdam, Netherlands, 286.

- Goodman LS. Goodman and Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1996.

- Dolphin, A. C. (1995). The GL Brown Prize Lecture. Voltage‐dependent calcium channels and their modulation by neurotransmitters and G proteins. Experimental Physiology: Translation and Integration, 80(1), 1-36.

CrossRef - Yamaguchi, S. I., and Rogawski, M. A. (1992). Effects of anticonvulsant drugs on 4-aminopyridine-induced seizures in mice. Epilepsy research, 11(1), 9-16.

CrossRef - Löscher, W. (1999). Valproate: a reappraisal of its pharmacodynamic properties and mechanisms of action. Progress in neurobiology, 58(1), 31-59.

CrossRef - Rabow, L. E., Russek, S. J., and Farb, D. H. (1995). From ion currents to genomic analysis: recent advances in GABAA receptor research. Synapse, 21(3), 189-274.

CrossRef - Meldrum, B. S. (2000). Glutamate as a neurotransmitter in the brain: review of physiology and pathology. The Journal of nutrition, 130(4), 1007S-1015S.

CrossRef - Dichter, M. A., and Brodie, M. J. (1996). New antiepileptic drugs. New England Journal of Medicine, 334(24), 1583-1590.

CrossRef - Rho, J. M., and Sankar, R. (1999). The pharmacologic basis of antiepileptic drug action. Epilepsia, 40(11), 1471-1483.

CrossRef - Sills, G. J. (2011). Mechanisms of action of antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsy, 295-303.

- Vogel, H. G. (Ed.). (2002). Drug discovery and evaluation: pharmacological assays. Springer Science and Business Media.

- Abayomi, S. (1993). Medicinal plants and traditional medicine in Africa. J Altern Complement Med, 13, 195-238.

- Bhat, S. D., Ashok, B. K., Acharya, R. N., and Ravishankar, B. (2012). Anticonvulsant activity of raw and classically processed Vacha (Acorus calamus Linn.) rhizomes. AYU (An International Quarterly Journal of Research in Ayurveda), 33(1), 119-122.

CrossRef - Raju, S. K., Basavanna, P. L., Nagesh, H. N., and Shanbhag, A. D. (1970). A study on the anticonvulsant activity of Withania somnifera (Dunal) in albino rats. National Journal of Physiology, Pharmacy and Pharmacology, 7(1), 17-17.

CrossRef - Alshabi, A. M., Shaikh, I. A., and Asdaq, S. M. B. (2022). The antiepileptic potential of Vateria indica Linn in experimental animal models: Effect on brain GABA levels and molecular mechanisms. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences, 29(5), 3600-3609.

CrossRef - Das K, Khan MS, Muthukumar A, Bhattacharyya S, Usha M, Venkatesh S, Sounder J. Phytochemical screening and potential anticonvulsant activity of aqueous root extract of Decalepis nervosa Wight and Arn. The Thai Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2022;46(3):307-15.

CrossRef - Pithadia, A. B., Navale, A., Mansuri, J., Shetty, R. S., Panchal, S., and Goswami, S. (2013). Reversal of experimentally induced seizure activity in mice by glibenclamide. Annals of Neurosciences, 20(1), 10.

CrossRef - Chiroma, S. S., Nazifi, A. B., Jamilu, Y. U., Musa, A., Bichi, L. A., and Chiroma, S. M. (2022).

Anticonvulsant activity and mechanism of actions of fractions of Ipomoea asarifolia (Desr)(Convolvulaceae) ethanol leaf extract. Bulletin of the National Research Centre, 46(1), 150.

CrossRef - Bhat, S. D., Ashok, B. K., Acharya, R. N., and Ravishankar, B. (2012). Anticonvulsant activity of raw and classically processed Vacha (Acorus calamus Linn.) rhizomes. AYU (An International Quarterly Journal of Research in Ayurveda), 33(1), 119-122.

CrossRef - Salim Mahmood, A., Ammoo, A. M., Ali, M. H. M., Hameed, T. M., Al-Hussaniy, H. A., Aljumaili, A. A. A., … and Kadhim, A. H. (2022). Antiepileptic effect of Neuroaid® on strychnine-induced convulsions in mice. Pharmaceuticals, 15(12), 1468.

CrossRef - Savairam, V. D., Patil, N. A., Borate, S. R., Ghaisas, M. M., and Shete, R. V. (2023). Evaluation of antiepileptic activity of ethanolic extract of garlic containing 3.25% allicin in experimental animals. Pharmacological Research-Modern Chinese Medicine, 8, 100289.

CrossRef - Serra, M., Ghiani, C. A., Motzo, C., Porceddu, M. L., and Biggio, G. (1995). Antagonism of isoniazid-induced convulsions by abecarnil in mice tolerant to diazepam. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 52(2), 249-254.

CrossRef - Serra, M., Ghiani, C. A., Motzo, C., Porceddu, M. L., and Biggio, G. (1995). Antagonism of isoniazid-induced convulsions by abecarnil in mice tolerant to diazepam. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 52(2), 249-254.

CrossRef - Hashimoto, A., Sawada, T., and Natsume, K. (2017). The change of picrotoxin-induced epileptiform discharges to the beta oscillation by carbachol in rat hippocampal slices. Biophysics and Physicobiology, 14, 137-146.

CrossRef - Baram, T. Z., and Snead III, O. C. (1990). Bicuculline induced seizures in infant rats: ontogeny of behavioral and electrocortical phenomena. Developmental brain research, 57(2), 291-295.

CrossRef - Heuzeroth, H., Wawra, M., Fidzinski, P., Dag, R., and Holtkamp, M. (2019). The 4-aminopyridine model of acute seizures in vitro elucidates efficacy of new antiepileptic drugs. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 13, 677.

CrossRef - Nordberg, J., Schaper, F. L., Bucci, M., Nummenmaa, L., and Joutsa, J. (2023). Brain lesion locations associated with secondary seizure generalization in tumors and strokes. Human Brain Mapping, 44(8), 3136-3146.

CrossRef - Schmoll, H., Badan, I., Grecksch, G., Walker, L., Kessler, C., and Popa-Wagner, A. (2003). Kindling status in sprague-dawley rats induced by pentylenetetrazole: involvement of a critical development period. The American journal of pathology, 162(3), 1027-1034.

CrossRef - Devinsky, O., Cilio, M. R., Cross, H., Fernandez‐Ruiz, J., French, J., Hill, C., … & Friedman, D. (2014). Cannabidiol: pharmacology and potential therapeutic role in epilepsy and other neuropsychiatric disorders. Epilepsia, 55(6), 791-802.

CrossRef - Tavakoli, Z., Dehkordi, H. T., Lorigooini, Z., Rahimi-Madiseh, M., Korani, M. S., & Amini-Khoei, H. (2023). Anticonvulsant effect of quercetin in pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-induced seizures in male mice: The role of anti-neuroinflammatory and anti-oxidative stress. International Immunopharmacology, 116, 109772.

CrossRef - Grigoletto, J., de Oliveira, C. V., Grauncke, A. C. B., de Souza, T. L., Souto, N. S., de Freitas, M. L., … & Oliveira, M. S. (2016). Rosmarinic acid is anticonvulsant against seizures induced by pentylenetetrazol and pilocarpine in mice. Epilepsy & Behavior, 62, 27-34.

CrossRef - Silva dos Santos, J., Goncalves Cirino, J. P., de Oliveira Carvalho, P., & Ortega, M. M. (2021). The pharmacological action of kaempferol in central nervous system diseases: A review. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 11, 565700.

CrossRef - Cheng, Y., Zhang, Y., Huang, P., Cheng, Q., & Ding, H. (2024). Luteolin ameliorates pentetrazole-induced seizures through the inhibition of the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway. Epilepsy Research, 201, 107321.

CrossRef - Blair, R. E., Deshpande, L. S., & DeLorenzo, R. J. (2015). Cannabinoids: is there a potential treatment role in epilepsy?. Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy, 16(13), 1911-1914.

CrossRef - Jones, N. A., Hill, A. J., Smith, I., Bevan, S. A., Williams, C. M., Whalley, B. J., & Stephens, G. J. (2010). Cannabidiol displays antiepileptiform and antiseizure properties in vitro and in vivo. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics, 332(2), 569-577.

CrossRef

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.