Manuscript accepted on : 16-04-2025

Published online on: 07-05-2025

Plagiarism Check: Yes

Reviewed by: Dr. Durgeshranjan Kar

Second Review by: Dr. Nicolas Padilla

Final Approval by: Dr. Haseeb Ahmad Khan

Akanksha Mansing Valvi , Rakesh Uttamrao Shelke*

, Rakesh Uttamrao Shelke* , Shantanu Sanjay Ghodke

, Shantanu Sanjay Ghodke and Dinesh Dattatray Rishipathak

and Dinesh Dattatray Rishipathak

Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, MET’s Institute of Pharmacy, Adgaon, Nashik, Maharashtra, India

Corresponding Author E-mail:rshelke07@gmail.com

DOI : http://dx.doi.org/10.13005/bbra/3379

ABSTRACT: The pharmaceutical sector is well-known for its Quality-by-Design (QbD) methodology, which has a significant impact on the analytical techniques and processes it uses. To highlight the importance of analytical chemistry in this industry's quality control system, "analytical quality-by-design" has also been advocated. All chemical industry branches do, however, have quality systems in place, with a significant portion of them being tied to chemical analysis and the corresponding quality control systems. With time, more green chemistry ideas will find their way into the manufacturing of chemicals, such as minimizing waste output, using less materials and energy, and incorporating analytical measurements into large-scale quality-control operations. The application of green chemistry principles to analytical chemistry aligns with the principles of Quality by Design (QbD) within that specific industry. This study presents a review of cases demonstrating the integration of green analytical methods into QbD.

KEYWORDS: Evaluation; Green chemistry; Green development; HPLC; Quality by design

Download this article as:| Copy the following to cite this article: Valvi A. M, Shelke R. U, Ghodke S. S, Rishipathak D. D. Quality by Design and Green Analytical Chemistry: A Review of Novel Approaches to Chromatographic Method Development. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(2). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Valvi A. M, Shelke R. U, Ghodke S. S, Rishipathak D. D. Quality by Design and Green Analytical Chemistry: A Review of Novel Approaches to Chromatographic Method Development. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(2). Available from: https://bit.ly/4dbyytp |

Introduction

In 1999, Anastas introduced the term “Green Analytical Chemistry,” describing it as the creation of analytical techniques aimed at reducing the production of hazardous waste. He emphasized the importance of environmental responsibility and pollution reduction in the design and evaluation of new analytical techniques.

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) is centered on creating eco-friendly analytical techniques by reducing the use of hazardous reagents, minimizing waste, and promoting sustainable chemical analysis. It originates from the broader field of “green chemistry,” which seeks to mitigate the environmental impact of chemical processes. GAC emphasizes several key strategies: replacing toxic reagents with safer alternatives, miniaturizing procedures to minimize the volume of chemicals used, and automating processes to enhance efficiency and reduce human exposure to hazardous substances.1These strategies significantly reduce the consumption of reagents and the generation of waste, thus mitigating the environmental impact. Additionally, GAC promotes the integration of on-line decontamination or passivation techniques, which involve treating waste as it is generated to neutralize harmful substances before they can cause environmental harm. This approach not only makes analytical methods greener but also supports the broader goal of sustainable chemistry by ensuring that the entire lifecycle of an analytical process, from sample preparation to waste management, is environmentally responsible. GAC thus represents a crucial advancement in the effort to make chemical analysis more sustainable and less harmful to the planet2 To align with sustainability standards, GAC offers extensive resources on green awareness, with a growing focus on green assessments over the past decade. This has included the development of various metrics to quantify the sustainability of methods. These tools not only guide scientists but also motivate them to adopt more environmentally responsible practices. The use of chemicals, energy use, sample volumes, extraction durations, and waste generation are among the important variables assessed. A number of reviews have recently looked at the suggested green metrics.3,4

Green chemistry is a fundamental approach in chemistry that seeks to harmonize chemical processes with sustainable development principles. It encompasses various strategies aimed at reducing the environmental impact of chemical reactions and products. In the context of analytical chemistry, this discipline plays a vital role in promoting sustainable development, provided that analytical procedures are not only high-quality characterized by sensitivity, precision, and accuracy but also adhere to environmental sustainability principles. The present assay provides a succinct synopsis of the development of green chemistry and its multifarious impacts, encompassing its impact on analytical Chemistry, academic research, and education. The discussion also highlights the distinction between “sustainability” and “greenness” in this context. As a result, we provide at least foundational insights into sustainability within analytical chemistry. It is our hope that these reflections will inspire further advancements in both green analytical chemistry and sustainable analytical chemistry.5In recent years, a significant focus in analytical chemistry has been on advancing green analysis and adopting environmentally friendly approaches. This includes selecting safer procedures, solvents, and techniques, as well as employing analytical methods that produce less hazardous waste. Many chemical processes traditionally rely on solvents for purposes such as dissolution, extraction, purification, and as carriers or mobile phases, in addition to their role in enhancing spectral properties. Similarly, the use of chemical indicators, oxidants, and color development reagents is fundamental to numerous analytical procedures.

This review explores the adoption of green and eco-friendly methods, reagents, solvents, and techniques in the analytical determination of various analytes.6 Green chemistry refers to the implementation of strategies and techniques that minimize or eliminate the use of hazardous materials in production, products, byproducts, solvents, and reagents, thereby reducing risks to the environment and public health.7,8 The design of materials or chemical processes is the main focus of green chemistry, with a special emphasis on four of the twelve important principles.9 All sciences, including chemistry and chemical engineering, are advancing rapidly, as evidenced by the increasing number of scientific publications and citations across various fields. Analytical chemistry is no exception, with modern methods offering unprecedented capabilities. Current technological and methodological advancements enable the detection of analytes at progressively lower concentrations, the separation of increasingly complex mixtures, and the achievement of higher precision and accuracy, all while requiring smaller sample sizes and improving analysis speed and simplicity. In addition to these developments, “green analytical chemistry “a term used to describe the emphasis on reducing new techniques’ negative environmental effects while boosting their safety is a major trend in analytical chemistry.10,11

Green chemistry also concentrates on developing synthetic procedures and goods that reduce or do away with the usage of dangerous materials. Environmentally friendly chemistry includes all phases of the chemical life cycle, such as the development, application, and elimination of chemicals. Green chemicals are recycled or break down into innocuous residues. Hazardous materials in the surroundings can damage flora and fauna because of things like ozone layer depletion and global temperature change. exhaustion and the creation of haze.12,13 The goal of green analytical chemistry (GAC) is to provide analytical techniques that are advantageous for analysts and the environment.14,15Using the GAC technique has a number of benefits, such as using less toxic chemicals and reagents, using energy-efficient equipment, and producing less trash. One quick and very efficient chromatographic method HPLC. Smaller size and more accurate columns are features of HPLC systems, which can be very important in laboratory environments.16,17 HPLC can handle any soluble substance, irrespective of its volatility. Choosing appropriate eco-friendly solvents can be facilitated by various solvent selection guidelines provided by different organizations.18,19

The methodology involves systematically analyzing existing literature to highlight advancements in integrating Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) principles with Quality by Design (QbD) approaches. The review begins by defining the role of GAC in minimizing environmental impact through the use of eco-friendly solvents, miniaturization techniques, and waste-reduction strategies. It then explores QbD principles, emphasizing Analytical Target Profile (ATP), risk assessment (Ishikawa diagrams), and optimization using Design of Experiments (DoE) to ensure method robustness and sustainability. The article also evaluates different greenness assessment tools, such as GAPI, NEMI, Analytical Eco-Scale, and AGREE, providing comparative insights into their effectiveness in quantifying the environmental impact of analytical methods. Additionally, case studies from various industries (pharmaceutical, food, and environmental analysis) are reviewed to demonstrate the practical implementation of these concepts. The methodology concludes by identifying challenges, future research directions, and the need for regulatory alignment, offering a comprehensive perspective on the evolution of green and QbD-based analytical method development.

Quality by design

Analytical chemistry is primarily used by pharmacists and chemical scientists in the industrial sector as an instrument for measurement to monitor the chemical reactions and ensure that technology and products meet high standards. Process Analytical Technology (PAT) focuses on monitoring and controlling analytical chemistry processes to support problem-solving and product composition analysis. The goal is to develop and oversee procedures that result in better final products a strategy known as QbD. The drug industry sets the standard for applying quality by design, to process development, and this has a direct bearing on the PAT methodologies and analytical procedures used. 20

The primary objective of Green Chemistry is to reduce or eliminate the harmful effects of various organic solvents on both the environment and human health. Analytical methods typically balance environmental considerations with safety. By integrating sustainable chemistry with Quality by Design (QbD) principles, it is possible to develop techniques that are both dependable and environmentally friendly.21

Green Chemistry was founded with the goal of minimizing or doing away with the harmful impact that organic solvents have on the environment and human health.22 Conventional analytical methods frequently sacrifice environmental impact and safety. GAC principles can be combined with quality by design to build durable and environmentally friendly techniques. The importance and advantages of integrating QbD and GAC in analytical methods are emphasized in this review. In order to obtain optimal performance, QbD offers a methodical and systematic approach to method development in pharmaceutical analysis.23 It centres on a comprehensive assessment and investigation of various approaches. Green sample preparation, waste minimization, the reduction in size of tools for analysis, and efficient waste treatment techniques are important facets of Green Analytical Chemistry.24 Analytical methods’ environmental friendliness is evaluated using tools like solvent selection recommendations, the AMVI methodology, and the HPLC-EAT. A vital statistical tool in QbD, experiment design, is essential to this procedure. To sum up, the integration of Green Analytical Chemistry with QbD yields the advantages of both strong methods and sustainable environmental practices. Economic benefits have also been shown by applying similar ideas to High Performance liquid chromatography and other bioanalytical techniques. But more research and development are required. Before a product is finished, quality and robustness are ensured through the use of QbD, which is becoming more and more significant..25

Green Analytical Chemistry

The Green Analytical Chemistry journal aims to spotlight eco-friendly approaches that are often underrepresented in other analytical chemistry publications but are growing in significance. The principal aim of the magazine is to curtail or eradicate the utilization of detrimental agents and mitigate the production of waste. Also seeks to promote the use of screening methods for simple qualitative analysis, designed to bypass the extensive sample processing typically required for comprehensive quantitative analysis in large laboratories, replacing these with on-site and in-vivo technologies.

Green is the colour linked to money and chlorophyll. Environmental activists have been fighting hard in recent years to promote sustainability, and “green” product marketing has become popular. The adoption and application of green chemistry principles has become imperative for chemists in all domains of the chemical sciences, encompassing fundamental and practical research, manufacturing, and instruction.26

The primary objective is to progress green analytical technologies’ foundational and applied aspects. The magazine will include both cutting-edge green analytical chemistry techniques and modified conventional methods, with a focus on technology appropriate for screening applications.27,28 These techniques’ effects on the environment will be thoroughly evaluated in light of factors like reagent toxicity, waste generation, energy usage, and user safety. Additionally, the journal will provide a thorough evaluation of each method’s balance between environmental sustainability and functionality, taking into account both analytical and practical considerations. Published research will aid in advancing green regulatory approaches in analytical chemistry, ultimately minimizing the environmental impact of human activities. The content will also support university educators in integrating Green Analytical Chemistry into their curricula.29,30

Greening Chromatography

Numerous articles discuss how chromatography can be made more environmentally friendly by utilizing smaller separation devices. or green solvents for e.g. Water likewise, “older” separation methods like gas chromatography (GC) and capillary electrophoresis (CE) are actually highly environmentally friendly methods. From a green chemistry perspective, these methods are advantageous when they are applicable and workable. However, CE and GC are not suitable for all compounds or complex sample matrices. Miniaturization offers a viable solution, with significant advancements being made in microfluidics and lab-on-a-chip technologies.31,32

Greening Detection

In analytical chemistry detection, many greening efforts have focused on in situ analytical techniques, particularly spectroscopic methods.33 From a green chemistry perspective, in situ analysis is beneficial as it enables real-time process monitoring and direct observation of hazardous or unsafe chemical synthesis. Additionally, it eliminates extra handling steps, which often lead to increased chemical and energy consumption. An example of such a technique is Raman spectroscopy, which has been integrated with microfluidic separation processes.34 Due to its ability to penetrate thick sapphire glass windows, Raman spectroscopy is well-suited for in situ analysis in high-pressure fluid systems.35,36 For instance, research has demonstrated that Raman spectroscopy can be used to determine solubility in SC-CO2. The application of Raman spectroscopy in processes, as an in-situ monitoring detector, for surface examination, and for in vivo biological system study demonstrated significant promise.

Green Development

To address society’s need for extensive information on the environment, products, and processes, much of the research in Analytical Chemistry relies on highly computerized methods. These methods incorporate various sample treatment and component separation techniques or utilize advanced detection technologies. One fundamental principle of green chemistry is the conservation of energy and materials through the integration of high-throughput systems. Another key aspect is the use of innovative materials, such as nanoparticles, microfilms, and micro-assays, which can significantly reduce waste and minimize the sample size required for analysis. The application of computing and communication technologies in chemical data analysis, particularly in sensor research and data management, streamlines the analytical process by reducing steps and energy consumption, aligning with green chemistry principles. However, despite these advancements, green chemistry remains underrepresented in analytical chemistry literature. The systematic incorporation of green chemistry principles into the selection of analytical methods for chemical data acquisition is still not well-established. Given the numerous books and review articles published on this subject in recent years, an increase in the development and refinement of analytical methods that adhere to green chemistry principles can be expected.37,38

Sample preparation and separation science are the areas of analytical chemistry that are most commonly discussed in relation to green chemistry since they use the greatest number of solvents and other reagents. As a result, recycling, replacing hazardous solvents, and using solvents sparingly are given top attention. The “3R” method stands for reduction, replacement, and recycling.39 Recycling, swapping out dangerous solvents, and utilizing solvents sparingly are therefore given great priority. The “3R” approach—Reduction, Replacement, and Recycling has driven the broader adoption of alternative solvents and the modernization of instrumental techniques. Additionally, it significantly impacts costs in large-scale analytical control laboratories.

Here are some examples:

R1-Reduction

The properties of solid supports and separation media change at high temperatures, increasing effectiveness and reducing the requirement for solvents.

Apart from requiring certain temperature-resistant packing materials, this technique has drawbacks, such as the possibility of thermally labile chemicals degrading on the column and solubility issues with hydrophobic molecules. Utilizing shorter columns, higher pressures, and narrow-bore columns, which have smaller particles, significantly lowers solvent use and waste production40

R2-Replacement

In preparative scale HPLC, supercritical CO2 is comparatively frequently utilized for the separation of physiologically active chemicals. Finding a substitute for the environmentally damaging acetonitrile is also a focus of intense research, with ethanol showing some encouraging results. Certain organic solvents are available, such as lactate esters derived from biomass feedstock. The employment of approved procedures, which contain acetonitrile as a required component, is mandated by several regulatory agencies, which poses a drawback to the novel eluents. Although ionic liquids are currently very popular solvents, they are unlikely to be useful in chromatographic procedures; instead, they may be useful in sample preparation techniques like extraction.41

R3-Recycling

To cut down on waste production, the lab should, whenever feasible, acquire the required equipment and recycle its solvents. Sadly, the energy requirements and high cost of this make it anything but a fully green solution.

A “4S” strategy was put up by M. Koel and M. Kaljurand for green analytical chemistry.42

S1-Specific Methods

Capillary electrophoresis (CE), which replaces HPLC in identical circumstances, is the best illustration of adopting alternative approaches to solve similar problems. Capillary electrophoretic techniques offer greater success than HPLC in various applications due to their flexibility, high-efficiency separations, reduced solvent usage, and faster analysis times. With CE, you can utilize a variety of detector types, chromatographic separation processes, and an infinite selection of separation medium (buffers). Systems for collecting CE samples can be used. Flow analysis is a well-known technique for addressing certain analytical issues. It can be used to develop batch processes that are unreliable and have a significant potential to reduce waste production and agent use. Using techniques that enable direct probe analysis with little sample preparation is another way to go with this strategy. In this context, several laser-based and optical techniques ought to be taken into account.43 Furthermore, spectroscopic techniques enable great selectivity and sensitivity to be maintained with straightforward, portable equipment, enabling in-situ or in-vivo real-time process monitoring and analysis.

S2-Smaller Dimension

The amount of solvents and chemicals used in the measurement (detection) steps is significantly reduced when measurements are carried out on a tiny silicon platform where customized micro systems incorporate several chemical handling processes. These compact devices can efficiently integrate analyte electrophoretic separation. One key advantage of miniaturization is its suitability for applications in bioscience and nanoscience, where only small sample sizes are available—such as individual cells, nanoparticles, or even single molecules.44 Additionally, miniaturization contributes to energy conservation. However, microchip systems require small-scale reactors, pumps, and valves, often facing connectivity challenges. To address these issues, the Lab-on-a-Valve (LOV) concept has emerged as an innovative solution for pressure-driven sampling on a miniature scale.45 This system effectively manages chemical vapor formation using programmable flow, enables non-chromatographic speciation, and supports renewable micro-solid phase extraction. Moreover, it facilitates on-chip optical and electrochemical detection, including autosensing techniques. Manipulating droplets of liquid samples is another way to solve interface problems in microfluidics. Single droplets are comparable to micro-sample vessels that can be used as reactors, extraction vessels, transportation devices for further analysis, and flexible input devices in other techniques such as CE. One such instance is the transportation of the separated analytes within the CE capillary to the CE column, where they are gradually fractionated into droplets. It takes less than fifteen minutes to do this process.46

S3-Similar Methods

There are occasions when it is possible to gather enough data on chemicals without pre-treating the samples, or when a device without any moving components can handle the entire procedure. For “labs-on-a-chip” prototypes, paper can be used as an inexpensive, flexible, renewable, and biodegradable substrate. This material is easily obtained and performs well in a range of chemical and biological tests. Because the material is permeable. After use, this “device” is easily disposed of.47

There is currently a growing selection of lateral flow devices accessible; for example, the typical pregnancy test combines immunoassay testing with porous materials or membranes. Modern mobile phones can capture images of response spots on paper and transmit them to a personal computer via the internet for further analysis. Using basic free software, a calibration curve can be generated, allowing for the completion of quantitative analysis.48,49

S4-Statistics

Mathematical manipulation of the test results could provide information about the Analyte Signals; that is, the output data could be used to mathematically deduce a signal related to a particular analyte. Chemometrics is a branch of science that analyses chemical measurement data to extract chemical information. It is the study of chemical science that applies mathematical and statistical methods to design or choose the best measurement procedures and experiment. A substitute for chemical data processing could be chemometrics, which allows the application of far less complicated measuring techniques that usually do not need sample pre-treatment and lead to faster analysis times. Typically, multivariate statistical methods are applied in this situation. This is an example of how near infrared spectroscopy was applied in conjunction with chemometrics as a fast way to determine if the specimen’s matrices were changed by exposure to mine tailings pollution or not compared to what would be expected from wild populations. It was possible to ascertain in this case how much the harvest season, the person’s place of origin, and the level of soil pollution affected their chemical profiles.50 Another example uses the NIR system to simulate the concentration of hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3-S-triazine in a propellant factory by combining it with quantitative chemometrics. A fibre-optic probe from the spectrometer was instantly inserted into the continuously agitated samples in order to record in situ spectra. The recommended NIR technique eliminated the need for chemical reagents and the waste produced during the whole prediction procedure. The results show how quickly, thoroughly, and effectively the near-infrared technology can eliminate potentially dangerous residues from standard analytical procedures. Additionally, it might be used to keep an eye on the amount of RDX used in the manufacture of solid propellants.51 The chemometric approach proves highly beneficial in combined methods like LC and IR due to its ability to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio, adjust background interference, eliminate unwanted signals and residual mobile phases, and resolve overlapping chromatographic peaks, even under challenging gradient conditions with low chromatographic resolution. 52,53 Additionally, significant cost savings can be achieved by utilizing large datasets for analysis and visualization. Exploratory data analysis aids in drawing conclusions without requiring an exhaustive chemical examination of each analyte. In this context, measurement results from chromatographic, electrophoretic, or spectroscopic techniques can be compared to a fingerprint—a unique profile representing the complex molecular composition of the sample. 54,55 Over time, the detailed information within a chemically complex sample can be further explored to identify individual components and uncover underlying data. 56,57 Fingerprint analysis is widely used for managing spectroscopic and chromatographic data, proving to be a powerful and efficient tool for quality control and assessing the authenticity of herbal products.58,59

Principles of green chemistry

|

Chart 1: Green chemistry |

The principles of Green Chemistry have been widely embraced across industries, government policies, education, and technological advancements globally.60 A central objective of the circular economy is to create a balance between economic growth, resource sustainability, and environmental protection. Green chemistry plays a crucial role in driving this transition by promoting sustainable practices within the chemical industry. Furthermore, it has a significant impact on the development of innovative approaches in various branches of chemistry, including analytical chemistry, where the principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) are applied. One of the major challenges lies in establishing a suitable method for evaluating the environmental impact of an analytical procedure, considering multiple factors. Several published strategies have been introduced to assess the ecological footprint of different analytical techniques. 61

The twelve principles of green chemistry were developed by EPA scientists Paul Anastas and John Warner and elaborated upon in their 1998 book, Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice. These principles focus on reducing or eliminating hazardous substances in the synthesis, production, and application of chemical products to minimize risks to both the environment and public health. While it is challenging to implement all twelve principles simultaneously in the design of a green chemistry process, efforts are made to incorporate as many as possible throughout different stages of synthesis.62

Prevention

Dealing with waste after it has been produced is less sustainable and less effective than preventing waste development. trash prevention, which is not only better for the environment and human health but also more economical than handling and discarding trash once it is created, is the primary tenet of green chemistry.63

The relevance of this theory becomes evident when one considers that the United States produces over twelve billion tons of solid waste every year, of which approximately 300 million tons are dangerous waste. The chemical sector accounts for 70% of this hazardous waste; toxic organic waste, particularly methanol and xylenes, is a significant contribution. Waste disposal costs account for 2.2 percent of the US GDP, and they are constantly increasing.

Harmful to both people and the environment, toxic organic waste is mostly produced during specific phases of chemical synthesis, which are commonly known as “dirty reactions.” These reactions involve the use of toxic reactants and solvents and are characterized by harsh conditions that lead to the formation of numerous toxic byproducts. Common reactions that produce such waste include halogenation, oxidation, alkylation, nitration, and sulfonation, all of which are widely used across various industrial sectors.64

While the chemical industry and other manufacturers have historically overlooked waste prevention, the core focus of green chemistry is to minimize waste generation. However, completely eliminating waste is practically impossible, as no raw material can be entirely utilized. When waste is discarded, it represents a permanent loss of valuable resources in the production-consumption cycle. Therefore, any effort to reintegrate these materials into the cycle is economically beneficial. It’s critical to determine first whether the production of trash might be prevented, and, if otherwise, to come up with strategies to optimize the amount of trash generated during production that is reused or otherwise put to good use.

Managing or mitigating the effects of hazardous, toxic, explosive, bio-accumulative, and waste chemicals is considered more favorable than attempting to control or prevent their synthesis altogether.65

Atomic economy

Design or conduct the chemical process in a manner that ensures the final product contains a significant amount of the reactants, minimizing the loss of raw materials.

In 1990, Barry Trost introduced the concept of synthetic efficiency known as Atom Economy (AE), also referred to as Atom Efficiency. The old Boots process technique of synthesis had a low economic efficiency, using only around 40% of the raw components. This was a major problem. A novel “green” ibuprofen manufacturing technique was discovered in the 1990s that required only 3 steps. With a yield of up to 99%, this novel technique produced almost perfect transformation of every intermediary ingredient into the final result, while enabling material regeneration and reuse throughout the process. Consequently, the procedure virtually minimized trash formation, exemplifying “green synthesis.66

To determine the percentage of atomic efficiency, use the following formula: % of atomic efficiency = (Mr of the desired product/Mr of all reactants) x 100 67

Less Hazardous Synthesis

Is a cornerstone of green chemistry, aiming to minimize the inherent risks connected with chemical procedure. It advocates for the design and execution of chemical reactions that produce minimal or no hazardous substances, prioritizing safety throughout the lifecycle of the chemical process, from raw material selection to the handling of by-products and waste. Traditional chemical syntheses often involve toxic reagents, intermediates, or by-products that pose risks to human health and the eco-system. This risk can manifest as harmfulness, flammability, explosiveness, or ecological damage. The principle of less hazardous synthesis challenges chemists to rethink these processes, focusing on minimizing or eliminating such dangers.

One way to achieve less hazardous synthesis is by choosing safer reagents and solvents that are less toxic or corrosive. For instance, water or ethanol can be used as solvents instead of more harmful organic solvents like benzene or chloroform. Additionally, the development of milder response circumstances like lower heat and pressures can reduce the likelihood of generating hazardous by-products or requiring harsh chemicals.68

Another approach is the use of alternative, greener catalysts that are less toxic and more selective, which can minimize unwanted side reactions that produce harmful substances. Moreover, Hazardous waste production can also be decreased by engineering reactions that are more efficient in terms of atom economy, meaning that a larger proportion of the starting elements are incorporated into the finished product. Ultimately, fewer hazardous chemical syntheses contribute to a safer working environment, lower regulatory and disposal costs, and a reduced environmental footprint. This principle underscores the broader goals of green chemistry to make chemical manufacturing not only more sustainable but also safer for all stakeholders involved.

This idea encourages the creation of synthetic processes that put the usage and production of materials with little or no toxicity to the environment and human health first. Biological enzymes can be used as a substitute for dangerous chemicals in industrial processes to increase efficiency and save costs.69

EX.- Conceptually simple, Asahi Kasei’s new polycarbonate (PC) production method substitutes CO₂ for hazardous carbonyl dichloride (COCl₂). Additionally, this method does away with the need for dichloromethane (CH3Cl₂) as a solvent. To make polycarbonate and ethylene glycol (C₂H₆O₂), the total reaction involves ethylene oxide (C₂H₄O), CO₂, and bisphenol-A (C₁₅H₁₆O₂).70

Designing Safer Chemicals

One of the hardest problems in creating safer products and processes is reducing toxicity without sacrificing a product’s usefulness or efficacy. Toxicology and environmental science concepts must be understood in addition to a thorough understanding of chemistry to achieve this balance. Due to their efficacy, Highly Reactive substances are frequently used by chemists for molecular transformations. These substances may, however, also interact with unanticipated biological targets and have negative consequences on both the environment and human health. Without a thorough grasp of the relationship between a chemical’s structure and its hazards, even the most skilled chemist may lack the necessary tools to address this challenge.

Innovative approaches to chemical characterization are necessary for success in toxicology, as it is acknowledged that hazard is a defect in molecular design that needs to be fixed from the beginning. One important chemical attribute that must be identified, evaluated, and controlled as part of an all-encompassing, systems-based approach to chemical design is the inherent danger of elements and compounds.

Now is the ideal time to start working together as toxicologists and chemists to develop a truly holistic, multidisciplinary strategy that will train the future generation of scientists to make safer compounds with the help of cutting-edge curriculum innovations. Toxicology is developing quickly, using molecular biology to understand the mechanisms underlying toxicity. The basis for formulating design guidelines that chemists might use to direct their efforts in producing safer chemicals is provided by an understanding of these mechanisms. As we enter a new chapter, we are prepared to light the way for a world that is more secure, more nutritious.71

Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries

Auxiliary compounds (solutes, separating agents, etc.) should be used sparingly or not at all when possible and shouldn’t be hazardous. Chromatographic separations, which need the use of massive volumes of solvents, raise environmental problems due to pollution. Numerous conventional organic solvents are hazardous, combustible, and caustic, and recovering them usually necessitates costly, heavy on energy distillation that results in large losses. This emphasizes the necessity of creating solvents that are more environmentally friendly.

The principle of “Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries” suggests the synthesis procedure should reduce, and Auxiliary chemicals should be avoided wherever possible. If their use is necessary, these substances should be non-hazardous. The long-term viability of the process, employee safety, security during the process, and environmental protection should all be given top priority when choosing appropriate substitutes for traditional organic solvents in accordance with the principles of green chemistry. The best solvents should be easily handled, quickly recyclable, have minimal volatility, as well as stability both chemically and physically.72 Based on their applicability, conventional solvents can be categorized as suitable, usable, or undesirable [Table 1].

Table 1: Solvent selection is based on their intended uses

|

Suitable |

Usable |

Undesirable |

|

Methanol |

Cyclohexane |

Pentane |

|

Ethanol |

Methylcyclohexane |

Hexane |

|

Propan-1-ol |

Heptane |

Di isopropyl ether |

|

Propan-2-ol |

Isooctane |

Dichloromethane |

|

Butan-1-ol |

t-Butyl methyl ether |

Chloroform |

|

T-butanol |

Acetonitrile |

Benzene |

|

Ethyl acetate |

Tetrahydrofuran |

Dimethyl acetate |

|

Isopropyl acetate |

acetic acid |

carbon tetrachloride |

|

Acetone |

Xylene |

Dimethoxymethane |

Replacing traditional organic solvents with recyclable alternatives, including ionic fluids, is currently a promising strategy.73 These are the salts that, when left at room temp., stay liquid. Ionic liquids provide safer chemical processes since they have a low vapor pressure and do not evaporate easily like volatile organic chemicals do.74

Design for Energy Efficiency

It is imperative to acknowledge the environmental and economic ramifications of energy requirements in chemical processes and to take steps to mitigate them. Whenever possible, synthetic operations should be carried out under room pressure and temperature. Several energy-saving techniques were developed in response to the 1973 oil crisis to maximize the effectiveness of each kilojoule utilized in manufacturing. Minimizing energy consumption requires adherence to the Principle of Energy Efficiency, commonly known as Design for Energy Efficiency.75

For example, Growers of tomatoes benefit from a greenhouse that uses leftover vapor from another nearby chemical processing facility to produce ammonia. The CO2 levels in these greenhouses are kept below 50%, which promotes plant growth. To further encourage the growth of tomato seeds, carbon dioxide that has been collected from greenhouse gases can be utilized as a bi-activator76

Use Renewable Feedstock

Whenever possible, renewable raw materials should be used instead of non-renewable ones, both technically and financially. Using renewable feedstocks whenever possible is emphasized by the 7th principle of green chemistry. For example, it is usually more advantageous to use materials that are renewable rather than a variety of waste-producing plastics. The trend of creating biodegradable plastics is a result of this. In the food business, biodegradable packaging is becoming more and more significant due to various variables like worldwide agricultural and energy resource demand, political developments, and changes in legislation.77

Utilizing renewable raw materials lowers the release of carbon dioxide and improves energy usage in the bioplastics manufacturing process. For instance, the Coca Cola makes bottles with blends of polyethylene that contain thirty percent, and Nature Works, an American firm, makes bottles made of lactic acid-containing polymer The fermentation of dextrose, which is normally made from maize starch, yields PLA; about 2.5 kg of corn are required to make 1 kg of lactic acid containing polymer.78

Reduce derivatives

Minimizing or avoiding unnecessary derivatization is essential, including the use of blocking groups, protection and deprotection steps, or temporary modifications to physical or chemical processes. These steps often require additional reagents and can lead to waste generation. Reducing the usage of chemical derivatives is only core tenets of green chemistry. This principle suggests that, whenever possible, physicochemical reactions involving the preventing and releasing of groups during synthesis be avoided.79

Catalyst

Higher atom economy processes can be made possible by the application of catalysts. Because catalysts themselves aren’t consumed by chemical reactions, they can be recycled again and don’t add to waste. They can make it possible to use reactions that, in ordinary circumstances, would not take place but also result in reduced waste.80

To support environmental protection, the principle of catalysis advocates for the use of biodegradable catalysts. These catalysts help to reduce energy consumption, avoid organochlorine compounds, and minimize water usage or waste. Throughout this process, enzymes remain unchanged and can be used repeatedly. They do not alter the energy levels of the reactants. While biocatalysts offer advantages such as faster reaction rates and greater specificity compared to non-biological catalysts, they can be limited by heat sensitivity and stability issues.81

Design for Degradation

Organic pollutants, such as halogenated compounds, cannot break down and can build up in the environment. Replace these chemicals as much as possible with ones that break down more quickly in the presence of water, UV radiation, or microorganisms. 82

Real-time Pollution Prevention

To ensure that they do not end up in the ecosystem, chemical goods should be designed to break down into innocuous compounds after they have served their intended purpose.

The principle of designing for degradation requires that chemical products be formulated to break down into environmentally harmless substances once their intended function is complete. Meeting this requirement can be achieved by adjusting technological parameters during process management and modifying auxiliary substances used at various stages of production. The goal is to minimize the creation of harmful by-products and maximize the recycling of waste materials for reuse in production83

Keeping an eye on a chemical reaction while it’s happening can assist stop dangerous and polluting compounds from escaping owing to mishaps or unanticipated reactions. Real-time monitoring makes it possible to identify warning signals and take appropriate action to avert or control an incident before it happens.84,85

Safer Chemistry for Accident Prevention

Working with chemicals is never completely risk-free. Nonetheless, risk can be reduced with effective hazard management. There are obvious connections between this concept and several other principles that address dangerous materials or goods. Processes should, if feasible, be structured to minimize risks in the event that eliminating exposure to hazards is not feasible.86,87

The Comparison of green analytical chemistry Methodologies with Conventional analytical chemistry Methodologies:

During the 1990s, Paul Anastas contributed to several publications on green analytical chemistry, emphasizing its significance within the broader framework of green chemistry and highlighting the necessity of transitioning toward environmentally sustainable practices. 88Specifically, Anastas highlighted its dual function in environmental conservation, stemming from the possibility that different analytical chemistry techniques could not only aid in the identification of potentially harmful environmental elements but also contribute to the accumulation of pollutants and other ecological issues.89 It is crucial to work toward making analytical procedures more environmentally friendly while still taking into account their sensitivity, accuracy, and precision.

Steps in the Development of an Ecological Mind-set in Analytical Laboratories:

Table 2: The Development of Environmental Awareness in Analytical Laboratories.

|

Chemurgical analytical chemistry |

Green analytical chemistry |

|

Research of new reagents |

Conscientious analytical methodology |

|

Enhancement of the analytical sensitivity and selectivity |

Efforts on automation and miniaturization |

|

No safety or environmental considerations |

Evaluation of reagents consumed and waste generation |

|

Down the drains disposal of residues |

On line treatment of wastes |

The rise in analysis activity on unfavorable environmental elements and environmental samples resulted in an increase in analytical wastes and a noticeable shift in the attitude of laboratories regarding the effects of their residues. The evolution of environmental awareness in analytical laboratories is evident (Table No. 2), driven by concerns over the negative impact of increasing reagent use and waste generation. This shift highlights a strong connection between ecological consciousness and the advancements in chemistry at the end of the 20th century. In this context, the concept of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) has provided significant opportunities from both academic and industrial perspectives.90

Goal Of Green Analytical Chemistry

Reduction of use of chemical elements

Proper waste management

Prevents pollution

Decrease in energy consumption

Avoid the release of toxic solvent

Minimize hazardous materials

Efficient utilization of raw materials

Quality by Design and Analytical Chemistry

In the business world, Analytical Chemistry is primarily used by chemists and chemical engineers as a measurement tool to track chemical technological processes, which is the primary method of technology and product quality control. Process Analytical Technology (PAT) incorporates analytical chemistry’s process monitoring and control features, primarily for troubleshooting and analyzing product composition. Its objective is to develop and maintain technological processes that ensure the production of high-quality goods. This approach aligns with the concept of Quality by Design (QbD). The pharmaceutical industry has been at the forefront of utilizing QbD to enhance technical processes, influencing both analytical methodologies and PAT. Literature suggests that combining the QbD approach with Risk Analysis and Design of Experiments aids in developing reliable chemical processes. These processes incorporate appropriate analytical monitoring and control measures to ensure product quality. 90,91

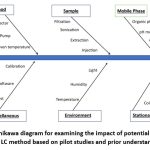

A fishbone diagram can also be used to illustrate sustainable production, which calls for the integration of green elements into every stage of the process. [ Figure 1].

|

Figure 1: Ishikawa diagram for examining the impact of potential variables on the LC method based on pilot studies and prior understanding |

The required resources for process sustainability and high-quality goods are shown in the figure. In this instance, all inputs materials, energy, and waste have a significant bearing on green chemistry and should be considered when creating procedures and end products to guarantee that they are suitable for the purposes for which they are designed.

These days, QbD is the primary focus of pharmaceutical development, and as a result, analytical chemistry is being thoroughly researched. Web of Science reports that the keywords “Analytical Quality by Design” are published in over 100 papers annually. It appears that the quality-by-design principle is increasingly being included into contemporary methods for process development in chemistry and pharmacy. First and foremost, for that, the evaluation of the intended product’s performance profile.92

Analytical Reagents

Customers look to analytical chemistry to (1) solve problems relating to compound purity or process and product safety and (2) provide enough quantities of pertinent elements and molecules. Chemical information about the object under study, both qualitative and quantitative, should be obtained with adequate accuracy and precision. A measurement process’s output must provide information that allows a user to make technically sound judgments for a specified goal

It is essential to acknowledge and utilize the diverse range of analytical techniques, protocols, and tools available, aligning them with the specific objectives of the analysis. According to ICH Guidelines Q8(R2) on Quality by Design, this approach involves a systematic development process that starts with well-defined objectives, focusing on product and process understanding, as well as process control, all grounded in scientific principles and quality risk management. You should refer to this material while you construct the quality-by-design analytical method. The excerpt highlights how crucial it is to choose the analysis method and the analysis procedure’s parameters of performance to achieve the study’s particular objectives. Following the Recommended Practice entails a change from a Quality by Testing strategy, in which batches that are released into the market or the final product are tested, to a more fully understood and efficient production process that enables adjustments to operational parameters, enhances measurement reliability, and offers regulatory flexibility. This strategy is in line with Green Chemistry’s tenets, which support real-time analysis to stop pollution. The concepts of Green Chemistry are naturally supported by waste management and chemical toxicity reduction, even though they are not usually addressed in quality control systems.

A comprehensive review published by T. Tome et al.93which references more than 70 research, emphasizes the expanding use of Quality by Design (QbD) in analytical evaluation procedures. The phrase “Analytical QbD” is emerging in the field of analytical chemistry as a result of this tendency. Using QbD to create process analytical systems gives more regulatory versatility throughout the course of the method’s lifespan, which is an important feature. This is accomplished by putting more emphasis on the method’s overall performance objectives than on strict instrument requirements.

While there are limited publications on integrating Green Chemistry principles with QbD, existing studies demonstrate that combining these concepts in analytical procedures can enhance environmental sustainability while maintaining the accuracy of the specific High performance liquid chromatography methods.

One prominent trend in research on analytical QbD is the replacement of acetonitrile, a typical HPLC solvent, with ethanol as a means of integrating green ideas into the design process. Similarly, in UHPLC, the selection of ethanol is based on its availability from renewable sources and reduced harmful effects. However, the use of ethanol adds new crucial elements to the separation process, necessitating meticulous method parameter optimization during the formulation of the analytical procedure as well as the experimental design phases.94

When considering the greenness of an analytical procedure, three key aspects should be taken into account: the specimen before treatment, the effectiveness of analytical tools, also the use of suitable waste treatment techniques in addition to disposal material reductions. Making an analytical technique more environmentally friendly usually starts with selecting the appropriate solvent, and there are established selection guides available to help with this decision. Parallel selection guidelines have been created for bases and acids. These guides are valuable for evaluating supplement compounds used in analytical methods. They focus on environmental, safety, and health concerns, particularly regarding the development of dangerous contaminants or difficulties with disposal. Y. Gaber used a comparable strategy.

Background of AQbD

|

Figure 2: The process of analytical method development in AQbD environment. |

The main steps of the AQbD process are the analytical target profile (ATP), risk assessment and examination, effectiveness, durability, and development of the method operable design region (MODR), as the AQbD workflow illustrates. A brief explanation of the particular procedure and most popular techniques for that stage are included in each box.

The goals of an analytical method are set by an Analytical Target Profile, which also specifies the precise measurements to be taken and the requirements for success, including accuracy, precision, and range, that must be fulfilled.95 Prior to beginning the method’s creation, it should be determined, outlining its goal but omitting to name the analytical approach. Therefore, the analytical procedure must be capable of accurately quantifying all identified or specified related substances and degradation products of an API, even in the presence of excipients and other drug product components. This should be achievable from the reporting limit up to 120% of their specification limit, maintaining an accuracy within ±20.0% of the actual value. An ATP supports regulatory bodies once the technique is approved, allowing for better ongoing method improvement. After defining the ATP, an analytical technique that meets the ATP criteria should be chosen. Various analytical techniques exist, each with its working principles, but HPLC is generally regarded as the most appropriate for impurity profiling analysis. It can be difficult to use due to the numerous operational factors, but if properly adjusted for the intended usage, it can produce results that are accurate and precise.

Response Modelling and Response Surface Design

A Response Surface Design is a more sophisticated classification of the DoE. In order to optimize a method’s operational effectiveness, this stage of the optimization process identifies crucial elements and how they interact with the prior screening design. A polynomial equation of higher order or a quadratic form can be used to describe the elements’ correlation with the responses after they have been studied at multiple scales (y = b0 + b1x1 + b2x2 + b11x1 + b22x2 + b12x1x2 + residual). For example, adding quadratic components to the model allows for the identification of nonlinear correlations between factors and responses, hence enabling the model to have curvature.53 When factors are studied at more than two levels, the testing area has a repeated centre point to determine the mistake caused by the experiment.96

|

Figure 3: a) A three-factor, two-level full factorial design consists of eight experiments, each represented by a green circle. |

b) A three-factor, two-level fractional factorial design, derived from the full factorial design, includes four experiments, each marked with a blue circle. c) A three-factor, three-level central composite design includes 15 experiments, which incorporates one experiment at the center point.

Response-surface designs include various experimental layouts, such as the Central Composite Design, Box-Behnken Design, Doehlert Design, and three-level full factorial design. Figure 5 illustrates the distribution of experiments in a three-dimensional space based on a Central Composite Design. When factor levels are restricted, a D-optimal design may be used to cover an asymmetrical experimental domain. Compared to screening designs, these designs necessitate significantly more experiments for an equivalent number of parameters. They are used to determine the mix of elements that predicts the best response since they can forecast responses for specific combinations of factors.

LC Method Development

This review includes a detailed examination of research articles published between 2016 and 2018, focusing on the application of Analytical Quality by Design (QbD) in the development of HPLC detection methods, particularly those involving UV measurements. This topic forms the second part of the review. The HPLC technique’s adaptability allows it to be applied to a variety of scenarios with various elution and retention strategies. This review covers instances where AQbD was used to create LC procedures for figuring out an assay or contaminants in tiny artificially created molecules. The representative sample matrix was one of three drug products: API, single dose, or a combination dosage. Furthermore, examples of utilizing different computer programs for DoE, examining obtained research results, and developing design space based on both.

Development of HILIC Method

Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography (HILIC) is a less commonly used technique compared to reversed-phase HPLC. In HILIC, the mobile phase is polar, containing at least 3% aqueous phase along with an organic solvent that is water-soluble. The moisture from the mobile phase adheres to the silicon particles in the stationary phase, creating a water layer that imparts polarity to the stationary phase. Therefore, HILIC ought to be able to retain strongly polar molecules adequately. Moreover, the HILIC separation process may utilize a number of retention mechanisms. Therefore, creation of particular HILIC approach could result in a less reliable method. Since retained pattern during HILIC separations is often poorly understood, an organized AQbD strategy for HILIC technique development should be adopted. 97

Combination of Drug Product

These days, combination medication products that contain more than one APIs are becoming more and more beneficial. Multiple targets in one dose form undoubtedly has benefits, and also it allows for considerably simpler drug product management for the patient throughout long-term treatment. The more APIs are used in a formulation, the more complex it becomes because each API exhibits unique chemical and physical characteristics. Therefore, if it is feasible to do so, the creation of only one single analytical technique for the characterization of a combination of therapeutic substances poses a significant challenge to all analytical scientists.

Optimization of Pharmacopeial Methods

Monographs from international pharmacopoeia are typically included in a literature evaluation at the outset of method development. In addition to saving time and money that would have been used on method development, adopting a pharmacopeial technique also ensures that the method will function reliably and fulfil its intended purpose. However, many pharmacopeial techniques that date back ten years or more may be considered archaic in modern times. Improved separations and up to ten times shorter analysis run times can be obtained using novel stationary phases containing sub-2 μm particles and advanced analytical instruments. The use of systematic techniques employing DoE for additional IP method optimization is encouraged by the likelihood that the method’s resilience was already evaluated by OFAT tests.

Impurity Profiling

A medicinal substance’s impurity profile is defined as “a description of the identified and unidentified impurities present in a new medicinal substance” by the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH). The method of analysing data to determine each impurity’s biological safety is known as impurity profiling. The purpose of impurity profiling is to keep the API stable or functional. The foundation of the pharmaceutical industry is the mass production of medications since it provides unique, high-quality active ingredients. Purity is a dynamic concept that is closely related to developments in analytical chemistry. Impurities in APIs are becoming more and more popular. Lately, both the purity profile and the impurity profile have gained importance due to different regulatory requirements. Impurities are defined as compounds of organic origin other than pharmaceuticals, synthetic components, or undesirable chemicals that are still present in the API in the pharmaceutical industry. Impurity profiles are becoming significant because of different regulatory mandates. Organic materials or undesirable compounds that are still present in an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) are referred to as impurities in the pharmaceutical business. Both the formulation process and the aging of the API can produce impurities. The identified and unknown impurities found in a typical batch of APIs made under specific, regulated manufacturing conditions are described in the impurity profile. One of the most crucial fields of study for the examination of contemporary industrial medications is this one. Guidelines on contaminants in new medications, goods, and residual solvents have been released by the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH). The effectiveness and safety of medications can be impacted by contaminants, even in trace amounts. Nowadays, synthetic medications are the most often used drugs, from which different final formulations are created. These formulations ensure bioavailability and therapeutic action by delivering medication in a stable, safe, and palatable form.

Other Methods

The value and effectiveness of software-assisted analytical techniques are demonstrated through their ability to optimize processes. Zoldhegyi et al.98 used software modelling to develop an automated UHPLC method for separating ten pharmaceutical compounds. The goal was to create a robust technique that achieved baseline separation and faster scanning times. Initial tests indicated the use of gradient elution in reversed-phase chromatography with a C-18 column. The gradient was set between 10% and 95% B, and several factors were optimized through the Design of Experiments (DoE), including gradient duration (5–15 minutes), column temperature (30–60 °C), and mobile phase B (a 50:50 mixture of ACN and CH3OH). This resulted in twelve experimental runs. After analyzing the data in Dry Lab 4, a model that closely matched the experimental results was developed. A 3D resolution map was created to visually represent the model, highlighting the MODR (Region of Maximum Desirability), where the Critical Method Attributes (CMA) were successfully met. At the chosen maximum working point, the shortest analysis time and an acceptable critical resolution may have been achieved. An examination of robustness was performed for the selected working point.

Greenness Assessment for Development Method

The method integrates tri-combinations for analyzing two medications, with all three factors being essential in the development of procedures. A solution cannot claim to be environmentally friendly without undergoing proper evaluation using the appropriate methodologies. Four assessment tools were utilized to evaluate the environmental impact of the method: the AGREE-Analytical Greenness Metric, the AGMS-Analytical Method Greenness Score, the GAPI-Green Analytical Procedure Index, and the NEMI-National Environmental Methods Index. Each of these tools offers a range of features, limitations, and evaluation techniques. The results of each assessment instrument will determine which design is the most ecologically friendly as well as the evaluation method to employ. Although this approach evaluation procedure used multiple technologies, all of the data were presented in an ecologically responsible manner. This is how the methodology was assessed: the entire amount must not be more than 50 ml. Because there is little loss as a result of the recycling process, the third quadrant was given a green tint. The primary NEMI picture of a method.99

NEMI

Nemi is a popular qualitative assessment method used to evaluate green chemistry. shown in (Figure 4). It was the only instrument available for assessing GAC efforts at first. NEMI offers advantages when examining the green analytical approach, even though it is creating new instruments for the GAC assessment. A sphere-shaped symbol with four quadrants and matching hues (green and colourless) is used to symbolize NEMI. In quadrant one, the EPA is in charge of handling the Persistent Bio-accumulative Toxic substances listed on the Toxicity Regulatory Inventory list.

In contrast, the Toxicity Compounds Regulation Inventory list of PBT compounds are subject of quadrant two’s work. Since the materials employed in this procedure are not included in PBT, this quadrant has a green hue. The second quadrant of the RCRA is occupied by hazardous substances, which are primarily regulated.

Because of the compounds that this method also discovered to be on the RCRA list, the second quadrant is displayed as green. The analytical solutions pH levels must be below a particular value, and the mobile phase ethanol plus phosphate buffer pH levels must be 60:40%. The 3rd region satisfies these criteria, making it a green zone. Waste is the topic of the fourth quadrant. The method showed perfect resilience, 100%, with the robustness module in Dry Lab 4 simulated a total of 729 experiments. Subsequently, the most significant parameter combinations were verified.

GAPI

GAPI, a somewhat altered NEMI, has 11 classifications and uses red, yellow, and green to denote hazard, tolerance, and environmental friendliness. In research work, 84procedure make the use of GAO for evaluation easy through the development of freely available software. The application, in which it has 11 simple steps to get the result, must have the method details that need to be evaluated entered.

AMGS

An alternative method for assessing health, security, and the environment is provided by the HPLC Environmental Assessment-HPLC-EAT and SHE-Safety, Health, and Environmental Assessment, which are integrated with AMGS. The AMGS was divided into three categories: environmental health and safety, solvent energy, and equipment. These three scores add up to the method’s overall score, which should be as low as feasible to take into account making the method as environmentally friendly as feasible. The ultimate outcome obtained for the suggested methodology was 1242.90. in (Figure 4). which, when entering the data needed into the calculator accessible exclusively through AES Green Computing University illustrated the designed model’s favourable environmental impact.

|

Figure 4: [A] NEMI, [B] GAPI, [C] AMGS. |

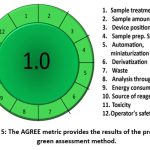

Agree with Metrics

AGREE WITH METRICS, the new Green Assessment instrument, contains all twelve of the green analytical concepts. The importance of the unique principles scoring obtained from the authorities of every individual was emphasized. Which was the overall result, which was represented as 1. The emphasis has placed on the individual principles score derived from each person’s rights. A value that is closer to one indicates how green the procedure is. After entering the specifics of the method into the application, (Figure 5). shows the overall result. Environmental effects of the approach have been characterized as “extremely benign” also “long-term sustainable.” While analysing approach’s greenness is done through five different methods or processes, the main goal was to determine how sustainable the method was. Whatever their strategies, every methodology revealed that this approach is safe for the environment and adaptable to future green assessments with no issues.100

|

Figure 5: The AGREE metric provides the results of the proposed green assessment method. |

Conclusion and Future Prospective

Pharmaceutical development and manufacture fundamentally rely on reliable analytical techniques, with High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UPLC) being the most commonly utilised for drug product analysis. With the escalation of formulation complexity, the development of analytical methods necessitates enhanced precision, accuracy, and robustness. The Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) framework provides a systematic, science-driven methodology that enhances method development by fostering a comprehensive understanding of analytical processes and establishing pre-defined objectives, such as the Analytical Target Profile (ATP).

Quality by Design (QbD) improves method reliability, decreases experimental workload, lowers costs and time, and guarantees optimal performance and reproducibility. The integration of AQbD with Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) principles enhances the creation of ecologically sustainable techniques by minimising the use of hazardous solvents and reagents while preserving analytical efficiency. To evaluate environmental effect, several green assessment methodologies are employed, including AGREE (Analytical GREEnness Metric), AGMS (Analytical Method Greenness Score), GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index), NEMI (National Environmental Methods Index), and the Analytical Eco-Scale. These instruments offer quantitative and visual evaluations that inform the selection and enhancement of more sustainable analytical methods.

Implementing green methodologies outside the AQbD framework may jeopardise performance and necessitate revalidation. Integrating AQbD, GAC, and HPLC technologies improves process robustness, sustainability, and regulatory compliance. This integrated approach guarantees uniform analytical excellence while advancing enduring environmental objectives. The comprehensive implementation of these approaches signifies an advanced approach in pharmaceutical analytics, harmonising with quality assurance and environmentally sustainable procedures.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the University of South Africa for providing research infrastructure.

Funding Sources

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

This statement does not apply to this article.

Ethics Statement

This research did not involve human participants, animal subjects, or any material that requires ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not involve human participants, and therefore, informed consent was not required.

Clinical Trial Registration

This research does not involve any clinical trials.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

Not Applicable

Author Contributions

Akanksha Mansing Valvi: Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing, review & editing.

Shantanu Sanjay Ghodke: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis.

Rakesh Uttamrao Shelke: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Conceptualization.

Dinesh Dattatray Rishipathak: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Investigation, Formal analysis.

References

- Płotka-Wasylka J and Namieśnik Jacek, Green Analytical Chemistry. (Płotka-Wasylka J, Namieśnik J, eds.). Springer Singapore; 2019. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-9105-7

CrossRef - Martínez-Pérez-Cejuela H, Gionfriddo E, Campíns-Falcó P, Herrero-Martínez JM, Armenta S. Green and sustainable evaluation of methods for sample treatment in drug analysis. Green Analytical Chemistry. 2024;10:100125. doi:10.1016/j.greeac.2024.100125

CrossRef - Abdelrahman, Maha Mohamed. Green Analytical Chemistry Metrics and Life-Cycle Assessment Approach to Analytical Method Development. In: Green Chemical Analysis and Sample Preparations. Springer International Publishing; 2022:29-99. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-96534-1_2

CrossRef - Sajid M, Płotka-Wasylka J. Green analytical chemistry metrics: A review. Talanta. 2022;238:123046. doi:10.1016/j.talanta.2021.123046

CrossRef - Płotka-Wasylka J, Mohamed HM, Kurowska-Susdorf A, Dewani R, Fares MY, Andruch V. Green analytical chemistry as an integral part of sustainable education development. Curr Opin Green Sustain Chem. 2021;31:100508. doi:10.1016/j.cogsc.2021.100508

CrossRef - Ghasemzadeh MA, Abdollahi-Basir MH. Ultrasound-assisted one-pot multi-component synthesis of 2-pyrrolidinon-3-olates catalyzed by Co 3 O 4 @SiO 2 core–shell nanocomposite. Green Chem Lett Rev. 2016;9(3):156-165. doi:10.1080/17518253.2016.1204013

CrossRef - Jurjeva J, Koel M. Implementing greening into design in analytical chemistry. Talanta Open. 2022;6:100136. doi:10.1016/j.talo.2022.100136

CrossRef - Anastas PT, Beach ES. Green chemistry: the emergence of a transformative framework. Green Chem Lett Rev. 2007;1(1):9-24. doi:10.1080/17518250701882441

CrossRef - Warner JC, Cannon AS, Dye KM. Green chemistry. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 2004;24(7-8):775-799. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2004.06.006

CrossRef - Anastas PT. Green Chemistry and the Role of Analytical Methodology Development. Crit Rev Anal Chem. 1999;29(3):167-175. doi:10.1080/10408349891199356

CrossRef - Becker J, Manske C, Randl S. Green chemistry and sustainability metrics in the pharmaceutical manufacturing sector. Curr Opin Green Sustain Chem. 2022;33:100562. doi:10.1016/j.cogsc.2021.100562

CrossRef - Constable DJC. Green and sustainable chemistry – The case for a systems-based, interdisciplinary approach. iScience. 2021;24(12):103489. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2021.103489

CrossRef - Badami B V. Concept of green chemistry. Resonance. 2008;13(11):1041-1048. doi:10.1007/s12045-008-0124-8

CrossRef - Petrovic M. Miguel de la Guardia, Sergio Armenta: Green analytical chemistry. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2011;400(7):1813-1814. doi:10.1007/s00216-011-4928-0

CrossRef - Sahu PK, Ramisetti NR, Cecchi T, Swain S, Patro CS, Panda J. An overview of experimental designs in HPLC method development and validation. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2018;147:590-611. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2017.05.006

CrossRef - Aboul-Enein HY. A Review of: “HPLC: A Practical User’s Guide, by Marvin C. McMaster, VCH Publishers, Weinheim, Germany, 1994, xii + 211 pp., DM 98.00; ISBN: 1-56081-636-8.” Instrum Sci Technol. 1995;23(4):335-336. doi:10.1080/10739149508014130

CrossRef - Bird IM. High performance liquid chromatography: principles and clinical applications. BMJ. 1989;299(6702):783-787. doi:10.1136/bmj.299.6702.783

CrossRef - Prat D, Pardigon O, Flemming HW, et al. Sanofi’s Solvent Selection Guide: A Step Toward More Sustainable Processes. Org Process Res Dev. 2013;17(12):1517-1525. doi:10.1021/op4002565

CrossRef - Ramalingam P, Jahnavi B. QbD Considerations for Analytical Development. In: Pharmaceutical Quality by Design. Elsevier; 2019:6:77-108. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-815799-2.00005-8

CrossRef - Saroj S, Shah P, Jairaj V, Rathod R. Green Analytical Chemistry and Quality by Design: A Combined approach towards Robust and Sustainable Modern Analysis. Curr Anal Chem. 2018;14(4):367-381. doi:10.2174/1573411013666170615140836

CrossRef - Poliakoff M, Licence P, George MW. UN sustainable development goals: How can sustainable/green chemistry contribute? By doing things differently. Curr Opin Green Sustain Chem. 2018;13:146-149. doi:10.1016/j.cogsc.2018.04.011

CrossRef - Carpentier CL, Braun H. Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development: A powerful global framework. Journal of the International Council for Small Business. 2020;1(1):14-23. doi:10.1080/26437015.2020.1714356

CrossRef - Ramtahal G, Chang Yen I, Bekele I, et al. Cost-effective Method of Analysis for the Determination of Cadmium, Copper, Nickel and Zinc in Cocoa Beans and Chocolates. J Food Res. 2014;4(1):193. doi:10.5539/jfr.v4n1p193

CrossRef - Hatzakis E. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy in Food Science: A Comprehensive Review. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2019;18(1):189-220. doi:10.1111/1541-4337.12408

CrossRef - Bitterlich A, Mihorko A, Juhnke M. Design Space and Control Strategy for the Manufacturing of Wet Media Milled Drug Nanocrystal Suspensions by Adopting Mechanistic Process Modeling. Pharmaceutics. 2024;16(3):328. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics16030328

CrossRef - Anastas P, Eghbali N. Green Chemistry: Principles and Practice. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39(1):301-312. doi:10.1039/B918763B

CrossRef - Chanduluru HK, Sugumaran A. Eco-friendly estimation of isosorbide dinitrate and hydralazine hydrochloride using Green Analytical Quality by Design-based UPLC Method. RSC Adv. 2021;11(45):27820-27831. doi:10.1039/D1RA04843K

CrossRef - Gałuszka A, Migaszewski Z, Namieśnik J. The 12 principles of green analytical chemistry and the SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic of green analytical practices. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry. 2013;50:78-84. doi:10.1016/j.trac.2013.04.010

CrossRef - Wojnowski W, Tobiszewski M, Pena-Pereira F, Psillakis E. AGREEprep – Analytical greenness metric for sample preparation. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry. 2022;149:116553. doi:10.1016/j.trac.2022.116553

CrossRef - Kannaiah KP, Sugumaran A, Chanduluru HK, Rathinam S. Environmental impact of greenness assessment tools in liquid chromatography – A review. Microchemical Journal. 2021;170:106685. doi:10.1016/j.microc.2021.106685

CrossRef - Patil MrMS, Patil DrRvindraR, Chalikwar DrShaileshS, Surana DrSJ, Firke DrSD. ANALYTICAL METHOD DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION: A REVIEW. International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biological Science Archive. 2019;7(3):66-69. doi:10.32553/ijpba.v7i3.126

CrossRef - Claux O, Santerre C, Abert-Vian M, Touboul D, Vallet N, Chemat F. Alternative and sustainable solvents for green analytical chemistry. Curr Opin Green Sustain Chem. 2021;31:100510. doi:10.1016/j.cogsc.2021.100510

CrossRef - Zou Y, Tang W, Li B. Mass spectrometry in the age of green analytical chemistry. Green Chemistry. 2024;26(9):4975-4986. doi:10.1039/D3GC04624A