Manuscript accepted on : 31-05-2025

Published online on: 11-06-2025

Plagiarism Check: Yes

Reviewed by: Dr. Ozlem Coşkun

Second Review by: Dr. Mohammed Oday

Final Approval by: Dr. Wagih Ghannam

Gauravi Sunilrao Kherde1* , Rahul Dnyaneshwar Khaire2

, Rahul Dnyaneshwar Khaire2 , Vikas Dhamu Kunde1

, Vikas Dhamu Kunde1 , Pooja Gajanan Akoshkar1

, Pooja Gajanan Akoshkar1 , Pratiksha Suresh katkade1

, Pratiksha Suresh katkade1 and Komal Sunil Taru1

and Komal Sunil Taru1

1Department of Pharmaceutics, PRES’s College of Pharmacy (For Women), Chincholi, Tal-Sinnar, Dist-Nashik , India.

2Department of Quality Assurance, PRES’s College of Pharmacy (For Women), Chincholi, Tal-Sinnar, Dist-Nashik , India.

Corresponding Author E-mail:gauravi.26001@gmail.com

DOI : http://dx.doi.org/10.13005/bbra/3380

ABSTRACT: The perfect properties of mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs), such as their wide surface area, large pore size, and biocompatibility, have attracted good consumers for topical medicinal goods in recent years. This systematic review focus to impart an in-depth outline of recent developments in MSN-based cosmetics and highlight their potential in dermatological and cosmetic applications. mesoporous silica nanoparticles provide a multiple platform for the encapsulation and prolonged release of numerous medical compounds, including anti-inflammatory and developmental drugs, thereby improving the therapy of numerous skin diseases like acne, psoriasis, and wounds. In addition, MSN are increasingly used to deliver antiaging and skin rejuvenating active ingredients, promote skin penetration, and enhance stability. This review also explores the challenges and strategies to optimize mesoporous silica nanoparticles structures to improve skin permeability, long-term drug release, and delivery. This article summarizes recent developments, highlighting a increasing potential of mesoporous silica nanoparticles based cosmetic techniques to improve clinical outcomes and attention to detail in dermatology, while also addressing future directions and research gaps in this field.

KEYWORDS: KIT-5; Mesoporous silica nanoparticles; MCM-41; SBA-16; MCM-50

Download this article as:| Copy the following to cite this article: Kherde G. S, Khaire R. D, Kunde V. D, Akoshkar P. G, katkade P. S, Taru K. S. Recent Advances in Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticle-Based Topical Delivery Systems: A Systematic Review. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(2). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Kherde G. S, Khaire R. D, Kunde V. D, Akoshkar P. G, katkade P. S, Taru K. S. Recent Advances in Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticle-Based Topical Delivery Systems: A Systematic Review. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(2). Available from: https://bit.ly/3ZsQQkl |

Introduction

To Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles

(MSN) was first introduced by Kuroda et al1.Japanese researchers and Mobil Oil Company researchers in the United States began investigating it as early as 1990. Within the 21st century, nanotechnology has developed crucial innovations in medicate conveyance. Cutting edge nanotechnology has been contemplate a collective stage for investigate in affiliation with the advancement of cutting-edge technologies. Nanomaterial has been utilized altogether within the community care division since of its highlight to grasp, convey, ensure and provide restorative specialists, especially to the focused on tissue and gives security by decreasing measurements estimate and recurrence of administrations.2

In recent years, mesoporous silica nanoparticles had made development in medical and diagnostic applications due to their characteristics like as uniformity, tunable porosity, mesoporous properties, compatibility, easy operationalization and noncontact nature, as well as multifunctional drug delivery systems3–5. Large mesoporous materials are constructed using self-build surfactant particles as a framework to condense silica prototypes in the surrounding area. Remove the framework and then construct the object in the mesh space. This new product family is characterized by the allocation of pores within the size range of 2 and 20 nm, a large pore size (about 1 cm3 g-1), an enlarged surface area (about 1000 m2 g-1) and their location. The silicon-dense group will be beneficial for the next line of work. These properties make mesoporous silica nanoparticles an ideal candidate for applications that may require adsorbed materials, such as drug delivery systems, as first proposed by the Valletâ Regà group in 2001.6 In addition to having chemical properties similar to bioactive glasses, bioceramics with a mesoporous structure show bioactive behaviour. Characteristics of mesoporous silica nanoparticles are shown in table 1.7,8

A huge wide variety of research has centered on the collaboration in-between surfactants and silica groups so that you can form a particular mesoporous silica nanoparticle. It’s miles terminated that mesostructural surfactant–silica nanocompoundes volutarily gather through interconnection of the natural and inorganic additives. Further to the thermostatics of the surfactant–silica assembly, the morphologies and dimensions of the ensuing compunds are mainly depending on the kinetics of sol–gel synthesis (including the heat of reaction, material water content, and pH value of the response answer). With a cautious manage of the self-arrangement and silica condensation charge, it’s miles feasible to tailor the sizes, mesostructures and arrangement of the mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Mesoporous silica nanocompounds, whose aspects include identical mesopores, clean modification and large compatibility, have received an awful lot of current interest for or their biomedical and catalytic applications.9,10

Researchers have effectively studied on the implementation of these carriers for stacking an assortment of cargo extending from drug components to macromolecules such as proteins 11,12 DNA 13,14 and RNA. 15,16 An inclusive set of written works are convenient, and investigations is still underway in analyzing unused roads for the utilization of MSNs in medicate conveyance. A few audits relating to MSNs in moving forward the solvency of the sedate, 17,18 as controlled/sustained medicate conveyance structure19 applications in biomedicine have been distributed.20,21

The mesoporous silica nano-compounds have one of the ideal characteristics, particularly in the large-scale stacking of useful operators and the ensuing discharges. Owing to solid Si-O bond, silica-based mesoporous nanoparticles are more steady to outside reaction such as debasement and mechanical push in comparision to niosomes, liposomes, and dendrimers which restrain the require of any outside stabilization within the blend of mesoporous silica nanoparticles.22,23 The surface functionalization is for the most part required to stack appropriate sort of sedate particles (hydrophobic/hydrophilic or positive/negative charged), By modifying some activities using chemical connections with other materials, such as stimuli-responsive, luminous, or capping materials, they may also have normal standards or attributes, leading to clever and multifunctional features.10

Table 1: Characteristics of Mesoporous silica nanoparticles essential for drug delivery

|

Characteristics |

Importance |

References |

|

Pore size |

Inner surface area amplification |

24 |

|

Particle size |

Reduced cytotoxicity in plants and animals due to boots endocytosis |

25 |

|

Pore volume |

Increase the capacity for medication loading |

2,26

|

|

Biocompatibility |

Stability in diverse biological settings |

27,28

|

|

Stability |

Resilient against corrosion Unaffected by mechanical, chemical, or thermal stress |

29,30

|

Importance of topical drug delivery system

There is currently an increasing need for treatments that can improve patient compliance, so cosmetic or pharmaceutical delivery is considered whenever possible.31 The ability to deliver bioactive molecules through the skin represents an area of interest as an substitute to the peroral or parenteral injection. This transdermal infant bypass the intestinal tract, avoiding the pre-systematic metabolism, is pain-free and allows self-management. Local delivery has the potential to eliminate the need for referral and reduce the total amount of drug required, thus minimizing adverse effects on the target.32 The plant can be used to treat skin inflammation, photoaging, microbial and fungal infections and cancer.33

Structural features of mesoporous silica nanoparticles

Mesoporous silica particle creation may have begun in the 1970s. The first business to create MSNs from aluminosilicate gels utilizing liquid lead liquid (Mobile Crystalline Materials or Mobile Composition of Matter) MCM-41 was Mobile Research and Development Corporation in 1992. According to IUPAC, mesoporous silica nanoparticles are substances with pore sizes, ranging from 2 to 50 nm and whose structural order determines the arrangement of their pores,34–36 MCM41 has a hexagonal crystal system with a pore size of 2.5 to 6 nm and uses a cationic surfactant as a template. MCM41 is one of the most widely distributed drug products. Various mesoporous materials were also formed by changing the initial component and reactants. They can differ in their configurations or pore sizes. While MCM48 has a cubic structure, MCM-50 has a layered structure. Types of Mesoporous silica nanoparticles are shown in table 2 and fig 1.37

Alkyl polyethylene oxide (PEO) oligomeric surfactants and polyalkylene oxides are examples of non-ionic triblock copolymers. Additionally, block copolymers have been used as models. The triblock polymer employed and the mesopore symmetry SBA-11 (cubic), SBA-12 (3D hexagonal), SBA-15 (hexagonal), and SBA16 (cubic lattice structure) have been chosen. To achieve the desired symmetry in the mesoporous material, the ratio of ethylene oxide to propylene oxide was altered. SBA-15’s porous structure is often used in biological applications 38 Many other MSNs are the Technical University of Delft (TUD1), the Hiroshima Mesoporous Materials33 (HMM33), Research Centre for Chemistry and Catalysis (COK-12) and their pores differ in symmetry and shape.39,40

|

Figure 1: Types of mesoporous silica nanoparticles

|

Table 2: Various types of MSNs.

|

Types of MSNs |

Pore Symmetry |

Pore Size (nm) |

Reference |

|

MCM-41 (Mobil crystalline material 41) |

2D hexagonal P6mm |

1.5-8 |

41,42 |

|

MCM-48 (Mobil crystalline material 48) |

3D cubic Ia3d |

2-5 |

41,42 |

|

MCM-50 (Mobil crystalline material 50) |

Lamellar p2 |

2-5 |

43,44 |

|

SBA 11 (Santa Barbara Amorphous) |

3D cubic Pm3m |

2.1-3.6 |

44–46 |

|

SBA 12 (Santa Barbara Amorphous) |

3D hexagonal P63/mmc |

3.1 |

20,47,48 |

|

SBA 15 (Santa Barbara Amorphous) |

2D hexagonal p6mm |

6-0 |

42,49 |

|

SBA 16 (Santa Barbara Amorphous) |

Cubic Im3m |

5-15 |

24,42 |

|

KIT-5 (Korea Advanced Institute of Science & Technology) |

Cubic Fm3m |

9.3 |

46,50 |

|

COK-12 (Centre for Research Chemistry & Catalysis) |

Hexagonal P6m |

5.8 |

51,52 |

Synthesis of MSNs

Sol-gel technique

Changed Another term for the sol-gel method is Stober’s procedure. In a controlled catalytic environment, this process involves the hydrolysis and condensation of tetraethyl orthosilicate, the precursor to silica. This approach uses both basic and acid catalysts. The alkoxide group hydrolysis is determined by the reaction circumstances and the molar ratio of silica to water molecules. pH speeds up the rate of hydrolysis. This process is aided by condensation. Interlinking results from hydrolysis and condensation. Multiple conjugations that enter the gel’s crosslinking structure result in a chain structure. In order to get components with the desired size and enhanced properties, the sol-gel process is used.25

Evaporation-induced self-assembly (EISA) method

Mahoney et al had first introduced the evaporation-induced self-assembly method. 27 Another process for formulation of mesoporous silica nanoparticles and patterned thin films. This process involves a number of steps, including the formation of primary nanoparticles, the diffusion of structuring agents, such as ionic or non-ionic surfactants, and inorganic pioneers in ethanol and water; quick solvent evaporation to accomplish inorganic encapsulation and film formation; the balance between the film’s water content and the ambient air; the development and stability of hybrid mesophases; and, lastly, conjugation to solidify the network structure. Many structure-directing compounds facilitate the growth of ordered mesoporous metal oxides for photovoltaics and sensing applications.28 The most popular forming agents are pluronic surfactants and amphiphilic block polymers. One of the main advantages of the EISA approach over another hydrothermal procedure is the quick synthesis of mesoporous silica nanoparticles.29

Microwave Assisted Synthesis

It aids in the creation of less expensive mesoporous silica nanoparticles by forming them hydrothermally, where heating forces the nucleation process. As opposed to the traditional convection heating method, it reduces the time needed for synthesis and particle size and speeds up polymerization; the rate of swelling of the material is higher than that of material made by conventional heating. This technique is primarily used in scientific research. Higher heating to the crystallization temperature, more supersaturation because precipitated gels dissolve more quickly, faster crystallization time, and higher heating are only a few of its numerous benefits over other general approaches,30 continuous nucleation is a result of ongoing heating during crystal development. Using this method, Wu et al. created a thermally stable hexagonal molecular sieve of MCM-41 molecules.53

Ultra-sonic Synthesis

Run et al.54 in 2004 discovered the ultrasonic synthesis technique for formation of mesoporous silica nanoparticles. This method results in the formation of well-organized hexagonal mesostructured with a large surface area of about 1100 m²·g⁻¹, the main pore size 22-30 angstrom and the volume of pore is about 1 cm³·g⁻¹. The one main merit of this synthesis technique is time required is highly reduce to minutes.55

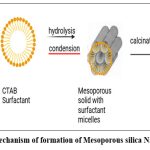

Mechanism

Both hydrolyzed silica adsorbs around the micelles, according to the data, and in the case of SBA-15, the silica and surfactant react in the preliminary phase to produce a core-shell, model 56. They can forecast the modifications that will take place concurrently with the design process by using this model. It has been discovered that silicate ions have a tendency to draw in the vicinity of the surfactant micelles during the development phase when tetramethyl orthosilicate (TMOS) hydrolyzes first on the silicate surface (approximately 40 seconds). Tiny silica clusters occur as a result of the early hydrolysis and condensation of the silica pioneers, which also reduces the quantity of surfactant surrounding the micelles and their repulsive force. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) examinations verified that the reaction mixture had sufficiently distinct hexagonally organized silica mesopores after around 400 seconds. This is in line with the “current knob model” of mesoporous silica nanoparticles production processes that was previously put out,57,58 Small Accelerator Xray Scattering (SAXS) machine. This process works well when tetraethylorthosilicate (TEOS) is used alone as lead without other solvents such as ethanol. TEOS is an oily monomer that exhibits phase separation under static conditions, while an emulsion-like structure is attained under pressure. Primarily, cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) forms ellipsoidal micelles with a core having hydrophobic tails. When TEOS is added, it dissolves in the hydrophobic core, thus expanding the micelle and causing the micelle shape to change from elliptical to spherical. When TEOS is hydrolyzed, the monomers become hydrophilic and are distributed into the liquid medium. The negatively charged TEOS hydrolyzable monomers are adsorbed onto the positively charged CTAB micelles via electrostatic attraction. When TEOS in the hydrophobic core is completely depleted, the micelles become minor and minor. Since the hydrolysis and condensation processes occur concurrently, the nanoparticles continue to form until all TEOS is hydrolyzed and a silica shell forms around the nanoparticles. Mechanism of formation of nanoparticles is shown in fig. 2. Adjacent nanoparticles clusters, leading to the growth of mesoporous structures.59

|

Figure 2: Mechanism of formation of Mesoporous silica Nanoparticles

|

Functionalization of MSNs

Modification of reaction parameters (relative amounts of alkoxysilane, water, catalyst) and temperature, the size, pore size, and morphology of mesoporous silica nanoparticles may be adjusted as desired.

Mesostructured Ordering

The pores available in MSN will possess different diameters based on which category of surfactant is used. The longer the length of the chain of the surfactant, the larger the pores of mesoporous silica nanoparticles, and the smaller the chain length, the smaller the pores of mesoporous silica nanoparticles 6,54,60,61. TEOS concentration affects the mesostructure arrangement of the goods. Greater amounts of TEOS show weak mesoporous structures, while smaller amounts are not sufficient to form mesoporous structures. 62 The amount of the surfactant CTAB was also found to have a significant effect on the microstructural properties of the material. A less surfactant concentration cannot form micelles, so the resulting nanoparticles will not have a structure, while excessive CTAB concentration can cause damage. 14 The addition of N,Ndimethylhexadecylamine (DMHA) can act as a pore modifier, thus helping to maintain the required pore size.63 Size of pore have direct impact on drug release rate which seen in ibuprofen.64,65

The mesostructured organization and pore size of the noncompounds are significantly impacted by the kind of surfactant used. Based on the alterations in the counterions shown in cetyltrimethylammonium (CTAB), the effect of templating agents was examined. Mesoporous, interdimensional silica nanoparticles were made using cetyltrimethylammonium chloride (CTAC) as a pore-forming template. The pore radius grew and the pore architecture changed from cylindrical to radiant after altering the reaction to a bigger tosylate ion (CTATOS).66 In order to address the drawbacks of conventional mesoporous silica nanoparticles, such as their tiny pore size and low particle size, researchers have recently used novel ways to alter the performance of MSNs. Given this, Huang et al.67 combined semi-fluorinated short chain anionic fluorocarbon surfactants, Capstone FS66 and CTAB, to create extremely monodisperse diphosphates with wide pores and dendritic morphology utilizing a unique dual templated solgel reaction nanoparticles. They carried out a qualitative investigation that demonstrated morphological alterations brought about by the addition of Capstone FS66. The particle has a dendritic channel pore structure and is larger. The picture transforms into a big dendritic structure that resembles a flower when more material is added. Yu et al. used the same concept to create dendritic MSNs with particle sizes greater than 200 nm by using Pluronic F127 as a particle growth inhibitor and imidazolium ionic liquids with varying alkyl lengths as cosurfactants. They discovered that the size of mesoporous silica nanoparticles was unaffected by either time or temperature.68

Control of Shape

Mesoporous silica nanoparticles’ cellular absorption and biodistribution are significantly influenced by their form. Thus, it is essential to tightly regulate the form of MSNs in order to regulate their excretion and other activities.69 Article by Huang et al.70 The potential of spherical MSNs for medication delivery has been extensively studied up to this point. The utilization of aspheric mesoporous silica nanoparticles is uncommon, nevertheless. Nonspherical materials in the form of cubes, flakes, films, sheets, ellipsoids, and rods will be created by carefully controlling the reaction. The shape of MSNs was discovered to be influenced by the molar concentrations of TEOS, water, base catalyst, and surfactant. Cai et al. created MSNs with a variety of morphologies, including spheres, silicon rods, and micron-sized oblate silica, by varying the amounts of TEOS, NaOH/NH4OH, and CTAB 71. By adjusting the concentration of dodecanol as soft template and the synthesis temperature, various silica particles with structures ranging from circular to shell-line, football-shaped, peanut-shaped, hollow and yolk-shell-like structures can be made. Six variables were created that provide control over the size, porosity, internal void and shell structure. Their analysis showed that the addition of dodecanol produced soft samples that produced different products with different morphologies.72 This indicates that any alteration to the nanoparticle structure during the first phase will result in a change to the morphology of the particles.

With varied ratios, MSNs may take on a variety of forms. Spherical MSNs often produce rod-shaped MSNs. By altering the sol-gel reaction’s negative reactions, they may be obtained. Rod-shaped MSNs may be produced by varying the temperature, introducing cosolvents such heptane, increasing the catalyst concentration, and altering the molar content of the reactants. 64,70 It is quite difficult for the cylinders to retain their shape due to the decrease in inertia force. These MSNs can be synthesized by adding surfactants73 adding potassium chloride and ethanol. 74 By adding a small amount of ammonium fluoride and heptane, 75 a non-ionic block copolymer P10476 is obtained using the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide-sodium dodecyl ternary surfactant system. Using a ternary surfactant system of cetyltrimethylammonium bromide–sodium dodecyl sulfate–Pluronic123.77

Drug Loading

The adsorption properties of mesoporous silica nanoparticles primarily determine the drug carrying capacity. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles may include hydrophilic and hydrophobic bundles within their pores. Because of their greater volume, MSNs may handle loads greater than conventional supports. Nonetheless, a lot of study has been done on improved medication delivery. Enhancing mesoporous silica nanoparticles loading may be achieved by the synthesis of HMSNs. Octadecyltrimethoxysilane (OTMS), 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES), and 3-cyanopropyltriethoxysilane (CPTES) are some of the silanes that He et al. attempt to functionalize. To improve the loading of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) in hollow mesoporous silica nanoparticles, surface silanol groups are used. Compared to 18.34% of free hollow mesoporous silica nanoparticles, the loading capacity of amine-functionalized HMSN was improved by 28.89%. Amino modified hollow mesoporous silica nanoparticles and negatively charged 5-FU may interact electrostatically to accomplish this. via altering the operating mode, a similar tactic to the chemical transport capacity via electrostatic attraction may be used.78,79 Because of their vacant area, hollow mesoporous silica nanoparticles have been shown to be better carriers in terms of loading than MSNs. Compared to mesoporous silica nanoparticles, hollow mesoporous silica nanoparticles has a 3–15 times greater drug loading. Additionally, the same carrier was used to carry two medicines.80 Using a polymer gate to trap hydrophobic materials may further increase the loading capacity of MSNs.81

Drug Release

Mesoporous silica nanoparticles’ drug release profile is mostly reliant on various pores, and by altering the MSNs’ surface, medications may be tailored to suit biological requirements. The cooperation between the drug molecules and the pore’s surface groups determines how the release is controlled.82 It was found that activating the drug first and then loading it to the active site with the amine group played a crucial role in promoting the release of the components compared to the systems where the drug was first activated and then loaded. This may be due to loading the drug into the pores and closing the APTES against drug discharge. If the site is first activated and then loaded, the drug will be adsorbed on the mesoporous silica nanoparticles surface, which will cause an explosion. investigated the role of APTES concentration on drug release and the results showed that changes in APTES concentration played an vital role in regulating drug discharge from the pores.83

Applications of Mesoporous silica nanoparticles in tropical drug delivery system

MSNs for Anti-Inflammatory applications

Different antibiotics have been hosted on MSNs and their release rates have been regulated thanks to their unique properties. There are two silica solutions: MCM-41 and SBA 15. Ibuprofen was carried by a variety of channels, and the response of its drug discharge was examined. Three phases of drug discharge were identified during the analysis of the data: first, the drug adsorbed on the MSN surface releases quickly, followed by a sustained release of the drug components in the surface’s tiny pores. Particles in MSNs have varying sample orientations. When the medication is fully integrated into the big pores of the particles, the last step of delayed discharge takes place.84 Most of the studies on the effective delivery of anti-inflammatory drugs by MSNs have used ibuprofen as an ideal drug. Works have been done to modify drug discharge by numerous changes of the silanol group. Surface functionalization has been shown to alter and enhance drug discharge.64,85

Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles for Antitumour therapy.

In an effort to enhance site-specific medication delivery and avoid negative responses, more research is being done on the surface functional characteristics of MSNs. It is a multipurpose vehicle that can be customized to provide effective therapy and loaded with medications that have unique physicochemical properties. Because of the effects of enhanced permeability and retention (EPR), they may group together in tumors.86 Increased cellular uptake of active medications is facilitated by active targeting. The right receptors found on tumor cells are selected, and particular ligands for these receptors are affixed to the surface of MSNs in accordance with the differences between normal and tumor cells. Target ligands may be loaded onto MSNs to provide targeted medication delivery. One known ligand that enhances the function of folate receptors on tumor cells is folate (FA).

The carboxyl group of FA and the amine group of aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES) form an amide bond, which facilitates FA incorporation on the surface of MSNs. In order to fight B16F 10 skin cancer, Ma et al.87 attached folic acid to the surface of HMSN and used 5-aminoethylpropionic acid for photodynamic treatment. It was shown that the development exhibited strong photosytotoxicity to tumor cells. According to the same study, amine functionalization on the surface makes it easier for folate to bind covalently to the receptor site so that tumor cells may preferentially absorb doxorubicin (DOX). Studies on cellular intake and apoptosis revealed that FA-MSN-NH2-DOX had a higher ability for cellular absorption than MSN-NH2-DOX.55

Gated Drug Release/Controlled Drug Delivery

Studies will continue to get intelligent, controlled release of the pharmaceuticals by capping the floor of the pores, even if the duration and the pore structure changed the drug launch charge. The gated launch makes it possible to transmit medications in a modified and intelligent manner to the target web page using MSNs. Only in response to certain stimuli, like as pH, temperature, enzymes, redox, and so on, do the gates of the pores open. When it comes to preventing dangerous adverse medication reactions to other organs, the gated drug launch principle may be quite effective.87 Several reviews on this consideration have been posted, some of which we’ve mentioned within the following segment.

pH-Responsive Drug Release

pH is a general science that determines drug release due to the wide range of pH values in the human body. Prednisolone loaded MCM48 particles were coated with succinate β-poly lysine (SPL) to provide pH-sensitive discharge of the drug in the colonic region. In vitro release procedure presented sustained drug release, indicating the success of the pH-sensitive drug delivery approach. At acidic stomach pH, SPL blocks drug discharge due to its ionized form, while at colonic pH, SPL converts to an ionized form that promotes molecular diffusion through MSNs. The produced nanoparticles can be used as an supportive therapy for intestinal diseases (colon cancer and colorectal cancer).88

Redox Responsive Drug Release

An other tactic often used to control carrier emissions is redox triggering. This gadget delivers antibodies using endogenous antibiotics. For this drug delivery, redox cleavable disulfide bonds are often used. For redox-sensitive drug delivery, Wang et al. created a disulfide-linked polyethylene glycol (PEG) that is affixed to mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Using rhodamine B (RhB) as a model medication, an in vitro release study evaluated the performance of the prepared MSNs. The release media was supplemented with glutathione (GSH) in an amount equivalent to the intracellular concentration. In the absence of GSH, it was shown that RhB discharge was negligible, demonstrating the cap’s ability to stop drug release. Furthermore, PEG surface modification gives the nanoparticles a high degree of biocompatibility.89

Temperature Responsive Drug Release

Thermosensitive mesoporous silica nanoparticles are also increasingly investigated as a way to control drug discharge. In this case, Bathfield et al. established copolymeric nanoparticles built on PEO-b-poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) as a model conducting material for the formulation of functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles. The sample drug, ibuprofen, was loaded into the mesopores using a well where the drug was directly integrated into the hybrid product. Finally, the structure-modifying agents in the development were drug-loaded polymer nanoparticles. Drug delivery profiles at 20°C and 45°C showed temperature-sensitive parameters drug release at 450 °C was higher than that at 200 °C.90

Chemical and Enzyme Responsive Drug Release

Many drugs and enzymes found in the body or prepared in bacteria have also been investigated for their ability to increase drug release from MSNs. Researchers have investigated the feasibility of glucose-based drugs in terms of drug delivery and their effectiveness in diabetes management. 91In a particular study, mesoporous silica nanoparticles with the function of the signal reporter alizarin compound ketone (ALC) were created. Glucosylated insulin is then absorbed into the pore via benzene-1,4 diboric acid (BA) -mediated esterification. Together it as a hypoglycemic agent and a pore blocker. Furthermore, rosiglitazone maleate was absorbed into the pore, forming multifunctional MSNs. Competition between ALC and BA occurs in the presence of glucose, which causes the pores to open and the medicine to be released.92

Current and Future perspectives

A few medicines have been granted by the FDA for therapy and use, but these new techniques have achieved significant breakthroughs in disease treatment and hold the potential to transform traditional approaches to treatment and diagnosis. Since the potential of employing MSNs as drug delivery vehicles was found, substantial study has been performed to determine the importance of this technology in the treatment of numerous illnesses. The majority of research have focused on the use of vectors for targeted anticancer medication delivery.

Although many studies confirm the effectiveness of mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) in topical delivery, some of the data may be explained differently. Certainly, the improvements in drug penetration and efficacy seen from MSNs can be caused by surfactants, penetration enhancers or co-administered components in the formulation, among other things. Likewise, how MSNs release their payload over time can depend not only on their pore structure and coatings, but also on pH, enzymes or the skin’s moisture level which change from one setting to another. Often, results seen in experiments with cell cultures do not match what happens in human skin. When we think about these options, we understand why we need thorough study and examination to clearly identify the influence of MSNs in therapeutic practices.

However, regulations and restrictions prevent the secure and effective interpretation and legal authorization of these compounds. In contrast to other nanocarriers, the production process of mesoporous silica nanoparticles is simple and efficient. In addition, these MSNs have additional potential due to their use as various nanocarriers for drug surfaces and bodies, as well as for theranostic and imaging purposes, as well as supporting various drugs. In this context, cell research and preclinical studies have achieved remarkable results. However, there are still many challenges in successfully translating this platform into hospitals. It may be very difficult to synthesize MSNs with the same properties and quality. The development of the technology mainly depends on the production capacity, therefore, the formulation of mesoporous silica nanoparticles at the manufacturing stage may have an impact on their commercialization. To ensure product recyclability, manufacturing processes need to be better understood and managed. Furthermore, since all medications are unlikely to be loaded uniformly, the value of mesoporous silica nanoparticles might vary depending on the context, which may aid in determining the maximum dosage of mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Chen et al. employed several analytical methods, such as customized fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) in conjunction with particle size/gel permeation chromatography (GPC), to assist preserve size and long-term stability, minimizing batch-to-batch variability. Although the mortality of most inorganic nanoparticles remains a significant worry, promising studies on the effectiveness and biocompatibility of mesoporous silica nanoparticles in animal models indicate that this platform might be adapted for medical usage.93

Conclusion

Advanced drug delivery systems for the skin often use MSNs, thanks to their ability to be adjusted, a large surface area and many surface uses. A review of new research demonstrates that MSNs support controlled drug release, increase the stability of drugs and help achieve targeted therapy for dermatology. This is especially useful in treats skin problems that continue for a long time since it releases medicine slowly right where it’s needed. The data I reviewed highlights that MSNs are now more widely used for anti-inflammatory, anticancer and stimulus-controlled drug delivery. Still, bringing MSN-based systems from the lab to clinical practice is currently a challenge. The problems of repeatability, safety with prolonged use, mass production and okaying by regulators are not fully solved yet. Informed by recent experiments, the conclusions here suggest an encouraging, but evolving, setting for MSN-enabled treatments. More interdisciplinary work is needed to solve current issues and make MSNs suitable for use in dermatology.

Acknowledgement

I would like the express their sincere gratitude to :Pres’s College of Pharmacy (for Women), chincholi, nashik for providing the necessary resources and support. Savitribai Phule Pune University, for its academic framework and infrastructure.I also acknowledge the contributions of the reviewers and editors for their valuable feedback and suggestions.

Funding Sources

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

This statement does not apply to this article.

Ethics Statement

This research did not involve human participants, animal subjects, or any material that requires ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not involve human participants, and therefore, informed consent was not required.

Clinical Trial Registration

This research does not involve any clinical trials.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

Not Applicable

Author Contributions:

Gauravi kherde: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Original draft

Khaire Rahul: Analysis, Writing- Review & Editing

Kunde Vikas: Visualization, Supervision

Katkade Pratiksha: Reviewing, Editing

Pooja Akoshkar : Reviewing, Data Collection

Komal Taru: Reviewing

Reference

- Yanagisawa T, Shimizu T, Kuroda K, Kato C. The Preparation of Alkyltrimethylammonium–Kanemite Complexes and Their Conversion to Microporous Materials. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1990;63(4):988-992. doi:10.1246/bcsj.63.988

CrossRef - Kresge CT, Leonowicz ME, Roth WJ, Vartuli JC, Beck JS. Ordered mesoporous molecular sieves synthesized by a liquid-crystal template mechanism. Nature. 1992;359(6397):710-712. doi:10.1038/359710a0

CrossRef - Amgoth C, Joshi S. Thermosensitive block copolymer [(PNIPAM)-b-(Glycine)] thin film as protective layer for drug loaded mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Mater Res Express. 2017;4(10):105306. doi:10.1088/2053-1591/aa91eb

CrossRef - Kankala RK, Han Y, Na J, et al. Nanoarchitectured Structure and Surface Biofunctionality of Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles. Adv Mater. 2020;32(23):1907035. doi:10.1002/adma.201907035

CrossRef - Li Z, Zhang Y, Feng N. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles: synthesis, classification, drug loading, pharmacokinetics, biocompatibility, and application in drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2019;16(3):219-237. doi:10.1080/17425247.2019.1575806

CrossRef - Vallet-Regi M, Rámila A, Del Real RP, Pérez-Pariente J. A New Property of MCM-41: Drug Delivery System. Chem Mater. 2001;13(2):308-311. doi:10.1021/cm0011559

CrossRef - Izquierdo-Barba I, Ruiz-González L, Doadrio JC, González-Calbet JM, Vallet-Regí M. Tissue regeneration: A new property of mesoporous materials. Solid State Sci. 2005;7(8):983-989. doi:10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2005.04.003

CrossRef - Hench LL. The story of Bioglass®. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2006;17(11):967-978. doi:10.1007/s10856-006-0432-z

CrossRef - Li Z, Barnes JC, Bosoy A, Stoddart JF, Zink JI. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles in biomedical applications. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41(7):2590. doi:10.1039/c1cs15246g

CrossRef - Lin X, Xie J, Niu G, et al. Chimeric Ferritin Nanocages for Multiple Function Loading and Multimodal Imaging. Nano Lett. 2011;11(2):814-819. doi:10.1021/nl104141g

CrossRef - Slowing II, Trewyn BG, Lin VSY. Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles for Intracellular Delivery of Membrane-Impermeable Proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129(28):8845-8849. doi:10.1021/ja0719780

CrossRef - Deodhar GV, Adams ML, Trewyn BG. Controlled release and intracellular protein delivery from mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Biotechnol J. 2017;12(1):1600408. doi:10.1002/biot.201600408

CrossRef - Cha W, Fan R, Miao Y, et al. Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles as Carriers for Intracellular Delivery of Nucleic Acids and Subsequent Therapeutic Applications. Molecules. 2017;22(5):782. doi:10.3390/molecules22050782

CrossRef - Tao C, Zhu Y, Xu Y, Zhu M, Morita H, Hanagata N. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles for enhancing the delivery efficiency of immunostimulatory DNA drugs. Dalton Trans. 2014;43(13):5142-5150. doi:10.1039/C3DT53433B

CrossRef - Möller K, Müller K, Engelke H, Bräuchle C, Wagner E, Bein T. Highly efficient siRNA delivery from core–shell mesoporous silica nanoparticles with multifunctional polymer caps. Nanoscale. 2016;8(7):4007-4019. doi:10.1039/C5NR06246B

CrossRef - Hanafi-Bojd MY, Ansari L, Malaekeh-Nikouei B. Codelivery of Anticancer Drugs and siRNA By Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles. Ther Deliv. 2016;7(9):649-655. doi:10.4155/tde-2016-0045

CrossRef - Riikonen J, Xu W, Lehto VP. Mesoporous systems for poorly soluble drugs – recent trends. Int J Pharm. 2018;536(1):178-186. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.11.054

CrossRef - Maleki A, Kettiger H, Schoubben A, Rosenholm JM, Ambrogi V, Hamidi M. Mesoporous silica materials: From physico-chemical properties to enhanced dissolution of poorly water-soluble drugs. J Controlled Release. 2017;262:329-347. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.07.047

CrossRef - Wang Y, Zhao Q, Han N, et al. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles in drug delivery and biomedical applications. Nanomedicine Nanotechnol Biol Med. 2015;11(2):313-327. doi:10.1016/j.nano.2014. 09.014

CrossRef - Mamaeva V, Sahlgren C, Lindén M. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles in medicine—Recent advances. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65(5):689-702. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2012.07.018

CrossRef - Tao Z. Mesoporous silica-based nanodevices for biological applications. RSC Adv. 2014;4(36):18961. doi:10.1039/c3ra47166g

CrossRef - Kwon S, Singh RK, Perez RA, Abou Neel EA, Kim HW, Chrzanowski W. Silica-based mesoporous nanoparticles for controlled drug delivery. J Tissue Eng. 2013;4:2041731413503357. doi:10.1177/2041731413503357

CrossRef - Liong M, Lu J, Kovochich M, et al. Multifunctional Inorganic Nanoparticles for Imaging, Targeting, and Drug Delivery. ACS Nano. 2008;2(5):889-896. doi:10.1021/nn800072t

CrossRef - Narayan R, Nayak UY, Raichur AM, Garg S. Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles: A Comprehensive Review on Synthesis and Recent Advances. Pharmaceutics. 2018;10(3):118. doi:10.3390/ pharmaceutics10030118

CrossRef - Danks AE, Hall SR, Schnepp Z. The evolution of ‘sol–gel’ chemistry as a technique for materials synthesis. Mater Horiz. 2016;3(2):91-112. doi:10.1039/C5MH00260E

CrossRef - Argyo C, Weiss V, Bräuchle C, Bein T. Multifunctional Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles as a Universal Platform for Drug Delivery. Chem Mater. 2014;26(1):435-451. doi:10.1021/cm402592t

CrossRef - Mahoney L, Koodali R. Versatility of Evaporation-Induced Self-Assembly (EISA) Method for Preparation of Mesoporous TiO2 for Energy and Environmental Applications. Materials. 2014;7(4):2697-2746. doi:10.3390/ma7042697

CrossRef - Liu C, Deng Y, Liu J, Wu H, Zhao D. Homopolymer induced phase evolution in mesoporous silica from evaporation induced self-assembly process. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2008;116(1-3):633-640. doi:10.1016/j.micromeso.2008.05.043

CrossRef - Hung CT, Bai H. Adsorption behaviors of organic vapors using mesoporous silica particles made by evaporation induced self-assembly method. Chem Eng Sci. 2008;63(7):1997-2005. doi:10.1016/j.ces. 2008.01.002

CrossRef - Kumar S, Malik MM, Purohit R. Synthesis Methods of Mesoporous Silica Materials. Mater Today Proc. 2017;4(2):350-357. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2017.01.032

CrossRef - Lee H, Song C, Baik S, Kim D, Hyeon T, Kim DH. Device-assisted transdermal drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2018;127:35-45. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2017.08.009

CrossRef - Goyal R, Macri LK, Kaplan HM, Kohn J. Nanoparticles and nanofibers for topical drug delivery. J Controlled Release. 2016;240:77-92. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.10.049

CrossRef - Prow TW, Grice JE, Lin LL, et al. Nanoparticles and microparticles for skin drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2011;63(6):470-491. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2011.01.012

CrossRef - Huo Q, Margolese DI, Stucky GD. Surfactant Control of Phases in the Synthesis of Mesoporous Silica-Based Materials. Chem Mater. 1996;8(5):1147-1160. doi:10.1021/cm960137h

CrossRef - Beck JS, Vartuli JC, Roth WJ, et al. A new family of mesoporous molecular sieves prepared with liquid crystal templates. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114(27):10834-10843. doi:10.1021/ja00053a020

CrossRef - Trewyn BG, Slowing II, Giri S, Chen HT, Lin VSY. Synthesis and Functionalization of a Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticle Based on the Sol–Gel Process and Applications in Controlled Release. Acc Chem Res. 2007;40(9):846-853. doi:10.1021/ar600032u

CrossRef - Øye G, Sjöblom J, Stöcker M. Synthesis, characterization and potential applications of new materials in the mesoporous range. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2001;89-90:439-466. doi:10.1016/S0001-8686(00)00066-X

CrossRef - Zhao D, Huo Q, Feng J, Chmelka BF, Stucky GD. Nonionic Triblock and Star Diblock Copolymer and Oligomeric Surfactant Syntheses of Highly Ordered, Hydrothermally Stable, Mesoporous Silica Structures. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120(24):6024-6036. doi:10.1021/ja974025i

CrossRef - Nandiyanto ABD, Kim SG, Iskandar F, Okuyama K. Synthesis of spherical mesoporous silica nanoparticles with nanometer-size controllable pores and outer diameters. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2009;120(3):447-453. doi:10.1016/j.micromeso.2008.12.019

CrossRef - Heikkila T, Salonen J, Tuura J, et al. Mesoporous silica material TUD-1 as a drug delivery system. Int J Pharm. 2007;331(1):133-138. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.09.019

CrossRef - Kumar D, Schumacher K, Du Fresne Von Hohenesche C, Grün M, Unger KK. MCM-41, MCM-48 and related mesoporous adsorbents: their synthesis and characterisation. Colloids Surf Physicochem Eng Asp. 2001;187-188:109-116. doi:10.1016/S0927-7757(01)00638-0

CrossRef - Wang S. Ordered mesoporous materials for drug delivery. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2009;117(1-2):1-9. doi:10.1016/j.micromeso.2008.07.002

CrossRef - Wang S, Li H. Structure directed reversible adsorption of organic dye on mesoporous silica in aqueous solution. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2006;97(1-3):21-26. doi:10.1016/j.micromeso.2006.08.005

CrossRef - Ukmar T, Planinšek O. Ordered mesoporous silicates as matrices for controlled release of drugs. Acta Pharm. 2010;60(4):373-385. doi:10.2478/v1007-010-0037-4

CrossRef - Zhao D, Wan Y, Zhou W. Ordered Mesoporous Materials. Wiley-VCH; 2013.

CrossRef - Kleitz F, Liu D, Anilkumar GM, et al. Large Cage Face-Centered-Cubic Fm 3 m Mesoporous Silica: Synthesis and Structure. J Phys Chem B. 2003;107(51):14296-14300. doi:10.1021/jp036136b

CrossRef - Lu GQ, Zhao XS, eds. Nanoporous Materials: Science and Engineering. Imperial College Press; 2004.

CrossRef - Ge S, Geng W, He X, et al. Effect of framework structure, pore size and surface modification on the adsorption performance of methylene blue and Cu2+ in mesoporous silica. Colloids Surf Physicochem Eng Asp. 2018;539:154-162. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2017.12.016

CrossRef - Galarneau A, Cambon H, Di Renzo F, Ryoo R, Choi M, Fajula F. Microporosity and connections between pores in SBA-15 mesostructured silicas as a function of the temperature of synthesis. New J Chem. 2003;27(1):73-79. doi:10.1039/b207378c

CrossRef - Javad Kalbasi R, Zirakbash A. Synthesis, characterization and drug release studies of poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate)/KIT-5 nanocomposite as an innovative organic–inorganic hybrid carrier system. RSC Adv. 2015;5(16):12463-12471. doi:10.1039/C4RA13930E

CrossRef - Jammaer J, Aerts A, D’Haen J, Seo JW, Martens JA. Convenient synthesis of ordered mesoporous silica at room temperature and quasi-neutral pH. J Mater Chem. 2009;19(44):8290. doi:10.1039/b915273c

CrossRef - Vialpando M, Aerts A, Persoons J, Martens J, Van Den Mooter G. Evaluation of ordered mesoporous silica as a carrier for poorly soluble drugs: Influence of pressure on the structure and drug release. J Pharm Sci. 2011;100(8):3411-3420. doi:10.1002/jps.22535

CrossRef - Wu C ‐G., Bein T. ChemInform Abstract: Microwave Synthesis of Molecular Sieve MCM‐41. ChemInform. 1996;27(35):chin.199635023. doi:10.1002/chin.199635023

CrossRef - Egger SM, Hurley KR, Datt A, Swindlehurst G, Haynes CL. Ultraporous Mesostructured Silica Nanoparticles. Chem Mater. 2015;27(9):3193-3196. doi:10.1021/cm504448u

CrossRef - Huang R, Shen YW, Guan YY, et al. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles: facile surface functionalization and versatile biomedical applications in oncology. Acta Biomater. 2020;116:1-15. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2020.09.009

CrossRef - Sundblom A, Oliveira CLP, Palmqvist AEC, Pedersen JS. Modeling in Situ Small-Angle X-ray Scattering Measurements Following the Formation of Mesostructured Silica. J Phys Chem C. 2009;113(18):7706-7713. doi:10.1021/jp809798c

CrossRef - Hollamby MJ, Borisova D, Brown P, Eastoe J, Grillo I, Shchukin D. Growth of Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles Monitored by Time-Resolved Small-Angle Neutron Scattering. Langmuir. 2012;28(9):4425-4433. doi:10.1021/la203097x

CrossRef - Edler KJ. Current Understanding of Formation Mechanisms in Surfactant-Templated Materials. Aust J Chem. 2005;58(9):627. doi:10.1071/CH05141

CrossRef - Yi Z, Dumée LF, Garvey CJ, et al. A New Insight into Growth Mechanism and Kinetics of Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles by in Situ Small Angle X-ray Scattering. Langmuir. 2015;31(30):8478-8487. doi:10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b01637

CrossRef - Yano K, Fukushima Y. Synthesis of mono-dispersed mesoporous silica spheres with highly ordered hexagonal regularity using conventional alkyltrimethylammonium halide as a surfactantElectronic supplementary information (ESI) available: time courses of particle size and scattering intensity of samples obtained with TEOS and C16TMACl. See http://www.rsc.org/suppdata/jm/b3/b313712k/. J Mater Chem. 2004;14(10):1579. doi:10.1039/b313712k

CrossRef - Ganguly A, Ahmad T, Ganguli AK. Silica Mesostructures: Control of Pore Size and Surface Area Using a Surfactant-Templated Hydrothermal Process. Langmuir. 2010;26(18):14901-14908. doi:10.1021/la102510c

CrossRef - Chiang YD, Lian HY, Leo SY, Wang SG, Yamauchi Y, Wu KCW. Controlling Particle Size and Structural Properties of Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles Using the Taguchi Method. J Phys Chem C. 2011;115(27):13158-13165. doi:10.1021/jp201017e

CrossRef - Gu J, Huang K, Zhu X, et al. Sub-150nm mesoporous silica nanoparticles with tunable pore sizes and well-ordered mesostructure for protein encapsulation. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2013;407:236-242. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2013.06.028

CrossRef - Muñoz B, Rámila A, Pérez-Pariente J, Díaz I, Vallet-Regí M. MCM-41 Organic Modification as Drug Delivery Rate Regulator. Chem Mater. 2003;15(2):500-503. doi:10.1021/cm021217q

CrossRef - Izquierdo-Barba I, Martinez Á, Doadrio AL, Pérez-Pariente J, Vallet-Regí M. Release evaluation of drugs from ordered three-dimensional silica structures. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2005;26(5):365-373. doi:10.1016/j.ejps.2005.06.009

CrossRef - Möller K, Bein T. Talented Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles. Chem Mater. 2017;29(1):371-388. doi:10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b03629

CrossRef - Huang M, Liu L, Wang S, et al. Dendritic Mesoporous Silica Nanospheres Synthesized by a Novel Dual-Templating Micelle System for the Preparation of Functional Nanomaterials. Langmuir. 2017;33(2):519-526. doi:10.1021/acs.langmuir.6b03282

CrossRef - Yu YJ, Xing JL, Pang JL, et al. Facile Synthesis of Size Controllable Dendritic Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;6(24):22655-22665. doi:10.1021/am506653n

CrossRef - Huang X, Li L, Liu T, et al. The Shape Effect of Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles on Biodistribution, Clearance, and Biocompatibility in Vivo. ACS Nano. 2011;5(7):5390-5399. doi:10.1021/nn200365a

CrossRef - Huang X, Teng X, Chen D, Tang F, He J. The effect of the shape of mesoporous silica nanoparticles on cellular uptake and cell function. Biomaterials. 2010;31(3):438-448. doi:10.1016/ j.biomaterials. 2009.09.060

CrossRef - Cai Q, Luo ZS, Pang WQ, Fan YW, Chen XH, Cui FZ. Dilute Solution Routes to Various Controllable Morphologies of MCM-41 Silica with a Basic Medium. Chem Mater. 2001;13(2):258-263. doi:10.1021/cm990661z

CrossRef - Han L, Zhou Y, He T, et al. One-pot morphology-controlled synthesis of various shaped mesoporous silica nanoparticles. J Mater Sci. 2013;48(17):5718-5726. doi:10.1007/s10853-013-7501-8

CrossRef - Hao N, Li L, Tang F. Facile preparation of ellipsoid-like MCM-41 with parallel channels along the short axis for drug delivery and assembly of Ag nanoparticles for catalysis. J Mater Chem A. 2014;2(30):11565. doi:10.1039/C4TA01820F

CrossRef - Shen S, Gu T, Mao D, et al. Synthesis of Nonspherical Mesoporous Silica Ellipsoids with Tunable Aspect Ratios for Magnetic Assisted Assembly and Gene Delivery. Chem Mater. 2012;24(1):230-235. doi:10.1021/cm203434k

CrossRef - Björk EM, Söderlind F, Odén M. Tuning the Shape of Mesoporous Silica Particles by Alterations in Parameter Space: From Rods to Platelets. Langmuir. 2013;29(44):13551-13561. doi:10.1021/la403201v

CrossRef - Cui X, Moon SW, Zin WC. High-yield synthesis of monodispersed SBA-15 equilateral hexagonal platelet with thick wall. Mater Lett. 2006;60(29-30):3857-3860. doi:10.1016/j.matlet.2006.03.129

CrossRef - Chen B ‐C., Lin H ‐P., Chao M ‐C., Mou C ‐Y., Tang C ‐Y. Mesoporous Silica Platelets with Perpendicular Nanochannels via a Ternary Surfactant System. Adv Mater. 2004;16(18):1657-1661. doi:10.1002/adma.200306327

CrossRef - Zhu Y, Shi J, Chen H, Shen W, Dong X. A facile method to synthesize novel hollow mesoporous silica spheres and advanced storage property. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2005;84(1-3):218-222. doi:10.1016/j.micromeso.2005.05.001

CrossRef - She X, Chen L, Li C, He C, He L, Kong L. Functionalization of Hollow Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles for Improved 5‐FU Loading. Falqui A, ed. J Nanomater. 2015;2015(1):872035. doi:10.1155/2015/872035

CrossRef - Chen F, Hong H, Shi S, et al. Engineering of Hollow Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles for Remarkably Enhanced Tumor Active Targeting Efficacy. Sci Rep. 2014;4(1):5080. doi:10.1038/srep05080

CrossRef - Palanikumar L, Kim HY, Oh JY, et al. Noncovalent Surface Locking of Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles for Exceptionally High Hydrophobic Drug Loading and Enhanced Colloidal Stability. Biomacromolecules. 2015;16(9):2701-2714. doi:10.1021/acs.biomac.5b00589

CrossRef - Nieto A, Colilla M, Balas F, Vallet-Regí M. Surface Electrochemistry of Mesoporous Silicas as a Key Factor in the Design of Tailored Delivery Devices. Langmuir. 2010;26(7):5038-5049. doi:10.1021/la904820k

CrossRef - Wang Y, Sun Y, Wang J, et al. Charge-Reversal APTES-Modified Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles with High Drug Loading and Release Controllability. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8(27):17166-17175. doi:10.1021/acsami.6b05370

CrossRef - Jadhav SA, Brunella V, Berlier G, Ugazio E, Scalarone D. Effect of Multimodal Pore Channels on Cargo Release from Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles. J Nanomater. 2016;2016:1-7. doi:10.1155/2016/1325174

CrossRef - Kamarudin NHN, Jalil AA, Triwahyono S, et al. Role of 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane in the preparation of mesoporous silica nanoparticles for ibuprofen delivery: Effect on physicochemical properties. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2013;180:235-241. doi:10.1016/j.micromeso.2013.06.041

CrossRef - Meng H, Xue M, Xia T, et al. Use of Size and a Copolymer Design Feature To Improve the Biodistribution and the Enhanced Permeability and Retention Effect of Doxorubicin-Loaded Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles in a Murine Xenograft Tumor Model. ACS Nano. 2011;5(5):4131-4144. doi:10.1021/nn200809t

CrossRef - Ma X, Qu Q, Zhao Y. Targeted Delivery of 5-Aminolevulinic Acid by Multifunctional Hollow Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles for Photodynamic Skin Cancer Therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7(20):10671-10676. doi:10.1021/acsami.5b03087

CrossRef - Nguyen CTH, Webb RI, Lambert LK, et al. Bifunctional Succinylated ε-Polylysine-Coated Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles for pH-Responsive and Intracellular Drug Delivery Targeting the Colon. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9(11):9470-9483. doi:10.1021/acsami.7b00411

CrossRef - Wang Y, Han N, Zhao Q, et al. Redox-responsive mesoporous silica as carriers for controlled drug delivery: A comparative study based on silica and PEG gatekeepers. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2015;72:12-20. doi:10.1016/j.ejps.2015.02.008

CrossRef - Bathfield M, Reboul J, Cacciaguerra T, Lacroix-Desmazes P, Gérardin C. Thermosensitive and Drug-Loaded Ordered Mesoporous Silica: A Direct and Effective Synthesis Using PEO- b -PNIPAM Block Copolymers. Chem Mater. 2016;28(10):3374-3384. doi:10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b00595

CrossRef - Zhao Y, Trewyn BG, Slowing II, Lin VSY. Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticle-Based Double Drug Delivery System for Glucose-Responsive Controlled Release of Insulin and Cyclic AMP. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(24):8398-8400. doi:10.1021/ja901831u

CrossRef - Zou Z, He D, Cai L, et al. Alizarin Complexone Functionalized Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles: A Smart System Integrating Glucose-Responsive Double-Drugs Release and Real-Time Monitoring Capabilities. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8(13):8358-8366. doi:10.1021/acsami.5b12576

CrossRef - Chen F, Ma K, Benezra M, et al. Cancer-Targeting Ultrasmall Silica Nanoparticles for Clinical Translation: Physicochemical Structure and Biological Property Correlations. Chem Mater. 2017;29(20):8766-8779. doi:10.1021/acs.chemmater.7b03033

CrossRef

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.