Manuscript accepted on : 18-06-2025

Published online on: 23-06-2025

Plagiarism Check: Yes

Reviewed by: Dr. Ersheng Gong

Second Review by: Dr. Deepa Manickam

Final Approval by: Dr. Fernando Lidon

Anuprabha1 , Varruchi Sharma2

, Varruchi Sharma2 , Vikas Kushwaha3*

, Vikas Kushwaha3*

1Department of Botany, Goswami Ganesh Dutta Sanatan Dharma College, Chandigarh, India.

2PG Department of Biotechnology and Microbial Biotechnology, Shri Guru Gobind Singh College, Chandigarh, India.

3Department of Biotechnology, Goswami Ganesh Dutta Sanatan Dharma College, Chandigarh, India.

Corresponding author E-mail: vikaskushwaha24@gmail.com

DOI : http://dx.doi.org/10.13005/bbra/3382

ABSTRACT: Raw meat (Chicken) contains various nutrients such as protein, essential fatty acids, minerals, vitamins, and high water content, making it a potential source of foodborne bacterial pathogens. This study aimed to evaluate the bacteriological quality of raw meats from open markets in Chandigarh, India. Fifty meat samples were collected from local markets in Chandigarh and stored at 4 °C. To assess bacteriological quality, a 10-fold serial dilution of the homogenate was performed, and the total viable count (TVC) and total coliform count (TCC) were determined using plate count agar. Morphological, biochemical, and molecular characterization techniques were used to identify bacterial isolates. The mean values of total aerobic count (TAC) in raw meat samples ranged between 2.77x10³ CFU/g and 3.19x10⁴ CFU/g, while the mean TCC values ranged between 3.54x10² CFU/g and 5.73x10² CFU/g. The study found a high prevalence of Escherichia coli (~80%), followed by Staphylococcus aureus (~58%), Salmonella spp. (~35%), Bacillus subtilis (~30%), Micrococcus luteus (~20%), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (~10%) in raw meat. The findings of this study highlight that raw meat samples from open markets carry a substantial microbial load, with the presence of various bacterial strains indicating potential contamination. This contamination poses a significant risk of foodborne illnesses, especially when meat is consumed raw or improperly cooked.

KEYWORDS: Food borne disease; Microbial pathogens; Raw meat; Total coliform count; Total viable count.

Download this article as:| Copy the following to cite this article: Anuprabha A, Sharma V, Kushwaha V. Unveiling the Bacterial Quality and Prevalence of Foodborne Bacteria in Raw Meat Sold at Different Markets in Chandigarh City, India. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(2). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Anuprabha A, Sharma V, Kushwaha V. Unveiling the Bacterial Quality and Prevalence of Foodborne Bacteria in Raw Meat Sold at Different Markets in Chandigarh City, India. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(2). Available from: https://bit.ly/4liw3IA |

Introduction

Meat (Skeletal muscles and their associated fat) is the flesh of animals, typically mammals or birds, which is consumed as food. It is a significant source of protein in the human diet and is often prepared by cooking, roasting, grilling, or other methods before being consumed. Common types of meat include beef, pork, lamb, poultry (such as chicken and turkey), and game meat. Meat has various essential nutrients, including protein, iron, zinc, and vitamin B12, making it an important part of many diets around the world and providing appropriate medium for microbes growth.1,2 Contamination of meat easily occurs during various stages, including animal processing, handling, transportation, and storage.3 Proper food safety practices, such as separating raw meat from other foods, storing at the correct temperature, and thoroughly cooking it, are essential to prevent foodborne illnesses associated with contaminated raw meat.4 Additionally, practicing good hygiene, such as washing hands and utensils after handling raw meat, further reduces the risk of contamination.5

Foodborne diseases are a significant public health issue occurs due to high risk of bacterial contamination by several types of pathogens that contribute to high morbidity and mortality globally.6 Every year, approximately 600 million instances of foodborne diseases and 420,000 fatalities are caused by contaminated food across the world. Young children under the age of 5 staggering 40% of the global burden of foodborne diseases. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), consuming unsafe food leads to the loss of approximately 33 million healthy life years (DALYs) each year.7 Globally, bacterial pathogens commonly linked to meat include Salmonella spp., Bacillus spp., Lactobacillus spp., Staphylococcus aureus, Campylobacter jejuni, Listeria monocytogenes, Clostridium spp., Yersinia enterocolitica, Brucell, Mycobacterium bovis, Aeromonas hydrophila, Salmonella species, Campylobacter spp., and verocytotoxin-producing E. coli O157:H7 that lead to self-limiting gastroenteritis, more severe invasive diseases and pose significant public health concerns. Additionally, Pseudomonas species are known to contribute to meat spoilage, resulting in undesirable characteristics such as off-odors, off-flavors, discoloration, and gas production.8,9 Observations have indicated that during the processes of slaughter, dressing, and cutting, the primary source of bacteria are the animal’s exterior and digestive system. However, additional sources such as blades, clothes, the surrounding air, workers, carts, crates, and equipment also contribute to bacterial presence.10 The introduction of various species of organisms suggests that under typical conditions, a substantial number of potential spoilage organisms exist and can proliferate if favourable conditions manifest.11 Keeping in mind that hygiene practices remain poor along the meat production and utilization, the present study was done to determine the prevalence of foodborne pathogens with special emphasis on Escherichia coli (E. coli), Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), Salmonella spp., Bacillus subtilis (B. subtilis), Micrococcus luteus (M. luteus), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) in marketed raw meat available in different areas nearby Chandigarh (UT), India.

Materials and Methods

Sample collection

Meat samples (Chicken meat) used in the study were collected from various areas (villages/colonies) surrounding Chandigarh in October month, including Daddu Majra, Dhanas, Hallomajra, Kaimbwala, Maloya, and Manimajra with poor sanitation and hygienic conditions (Figure 1). Total 50 unpacked raw meat samples were collected from different retail outlets from these regions. Approximately 50 grams of meat samples were carefully collected in clean, dry, and sterile polythene bags to ensure sample integrity. The samples were stored at 4°C to maintain sample quality and prevent microbial growth for further analysis.

Samples processing

The chicken meat samples were meticulously cut into thin, smaller pieces (1×1 c.m.) under aseptic conditions to prevent contamination. Each analytical portion of meat sample (size: 1×1 c.m. and weight: 10g) was then placed in an individually autoclaved 1.5 ml eppendorf tube, followed by the addition of 4 ml of 0.1% buffered peptone water (Himedia, India) to support microbial analysis. The tubes were centrifuged for 10 min at 1500 rpm (Eppendorf Centrifuge 5804R, Germany), supernatant was collected to spread on different media for isolation and characterization of different microorganisms.

Bacteriological analysis of samples

Total aerobic count (TAC), total coliform count (TCC), and isolation of different bacterial strains were carried out according to method of Bantawa et al.12 Briefly, homogenate sample suspensions were prepared in 0.1% buffered peptone water (Cat. No.: M028; Himedia, India) and then serially diluted tenfold (10⁻² to 10⁻⁴). Subsequently, 0.1 ml aliquots from each dilution were inoculated onto specific culture media: MacConkey Broth (Cat. No.: MM083; Himedia, India) for the cultivation of Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa; nutrient broth (Cat. No.: M002G; Himedia, India) for Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, and Micrococcus luteus; and lactose broth (Cat. No.: M1003; Himedia, India) for Salmonella spp. These cultures were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. Three to four well-isolated colonies from the primary cultures were subcultured onto selective agar media for identification: HiCrome™ E. coli Agar (Cat. No.: M1285I; Himedia, India) for E. coli; Staphylococcus Agar No. 110 w/ Azide (Cat. No.: M156; Himedia, India) for S. aureus; Xylose Lysine Deoxycholate Agar (Cat. No.: SPH031; Himedia, India) for Salmonella spp., Tryptone Soya Broth (Cat. No.: M011; Himedia, India) for B. subtilis; Mannitol Salt Agar (Cat. No.: SMH118C; Himedia, India) for Micrococcus luteus.; and Cetrimide Agar (Cat. No.: M024; Himedia, India) for P. aeruginosa.

Microscopy and colony morphology identification

The initial characterization and identification of bacterial isolates involved a detailed macroscopic examination of the colonies on the plate. This included assessing key morphological features such as colony size, appearance, edge, elevation, form, consistency, odor, opacity, color, hemolysis, and pigmentation. These attributes provided essential insights into the unique characteristics of each colony. The pathogenic bacteria were initially identified using Gram’s staining from the colonies.13

Biochemical characterization

Biochemical characterization of the bacterial isolates was performed by various biochemical tests viz. catalase, oxidase, citrate, Indole, Methyl red (MR), Voges Proskauer (VP), and nitrate reduction were performed for identification of bacterial isolates. All assays were performed using Cappuccino Sherman’s Manual of Microbiology, with some minor modifications.14

Catalase test

The catalase test was performed using the Cappucino and Sherman’s method. Colonies cultured overnight were carefully transferred onto a glass slide and treated with 1-2 drops of 3% hydrogen peroxide. The appearance of gas bubbles on the slide indicated a positive catalase reaction, confirming the enzyme’s presence in the sample.15

Oxidase test

A thin smear of each isolates was prepared on filter paper soaked with tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride and incubated for 10-30 min. A color change to deep blue or purple indicated an oxidase-positive result, while no color change (remaining white) showed an oxidase-negative result.15

Citrate test

An overnight-grown colony was carefully streaked onto a Simmons citrate agar slant and incubated at 37°C for 7 days. A color change from green to intense blue in the agar indicated a citrate-positive result, while a lack of color change, with the agar remaining green, showed a citrate-negative result.15

Indole test

The indole test was performed to assess the ability of microbes to break down the amino acid tryptophan into the organic compound indole. Microbial colonies grown on agar were treated with Kovac’s or Ehrlich’s reagent. A pink or red color indicated indole-positive microbes, while the absence of color change showed an indole-negative result.15

Methyl red test

Microbes were cultured in a sterile medium at 35-37°C for 2-5 days. Following incubation, a few drops of Methyl Red reagent were added to broth. A color shifts to red signified a methyl red positive result, while the absence of color change indicated a methyl red negative result.15

Voges-Proskauer test

A pure microbial culture was inoculated into MR/VP broth and incubated at 35°C for 24 to 48 hours. After incubation, a 1 ml sample was transferred to a fresh test tube, where 0.6 ml of 5% alpha-naphthol and 0.2 ml of 40% KOH were added. The tube was gently shaken and then left undisturbed for 10 to 15 min. A pink-red color at the surface indicated a positive result for this test.15

Nitrate reduction test

A pure culture of the microbe was inoculated into a liquid medium and incubated at 35°C for 24 hours. After incubation, a 1 ml sample was taken and transferred to a fresh test tube. To this, 0.1 ml of a freshly prepared test reagent (made by combining equal volumes of Solution A-8.0 g sulfanilic acid in 1 L of 5 mol/L acetic acid and Solution B-5.0 g α-naphthylamine in 1 L of 5 mol/L acetic acid) was added. The appearance of a red color within 30 seconds confirmed the presence of nitrites, indicating a positive result for nitrate reduction.15

Molecular identification of bacterial strains by PCR

Genomic DNA isolation and amplification of the 16S rRNA gene

Genomic DNA of bacterial strains was extracted from log-phase bacterial isolates using the PureLink Genomic DNA Mini Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the cell lysate was treated with lysis buffer, transferred to the spin column, and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 1 minute at room temperature. Subsequently, the collection tube was replaced with a new one, and the column was washed twice with 500 μl of Wash Buffer prepared with ethanol. The DNA was then eluted with elution buffer (25-50 μl) and stored at −20°C. The purity and quality of each extracted DNA were assessed using a NanoDrop 2000C spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

The full length of 16S rRNA gene was amplified through conventional PCR using the 16S rRNA primers of isolated bacterial strains (Table 1). A total reaction volume of 25 μl was used which contained 5μl (50ng) of genomic DNA, 1.5 μl (15 pmol) of each forward and reverse primer, 12.5 μl of 2X Master Mix and 6.5 μl of nuclease free water. Then reaction tubes were placed in the PCR thermocycler. PCR conditions were set to be as follows: initial denaturation for 5 minute at 95oC, denaturation of 30 cycles each 1 minute at 94oC, annealing for 1 minute at 60oC and extension for 30 second at 72oC, and final extension at 72oC for 10 minute. The size of the amplified products was checked using 1% (w/v) agarose gel electrophoresis and sequenced.16

Table 1: 16S rRNA primer for molecular identification of isolated bacterial strains by PCR.

| Bacterial strain | Sequence (5′->3′) | Length | Start | Stop | Tm | GC% | |

| Escherichia coli(NR_0245570) | Forward primer | AAGAAGCACCGGCTAACTCC | 20 | 486 | 505 | 60.04 | 55.00 |

| Reverse primer | TCTTTTGCAACCCACTCCCA | 20 | 1423 | 1404 | 59.74 | 50.00 | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa(DQ777865) | Forward primer | TGCCTGGTAGTGGGGGATAA | 20 | 119 | 138 | 59.95 | 55.00 |

| Reverse primer | TCTCAGCATGTCAAGGCCAG | 20 | 991 | 972 | 60.04 | 55.00 | |

| Staphylococcus aureus(NR_1189972) | Forward primer | AGGTAACGGCTTACCAAGGC | 20 | 265 | 284 | 60.04 | 55.00 |

| Reverse primer | GTTTGTCACCGGCAGTCAAC | 20 | 1181 | 1162 | 59.97 | 55.00 | |

| Salmonella enterica(NR_041696.1) | Forward primer | GTGAGGTAACGGCTCACCAA | 20 | 238 | 257 | 59.97 | 55.00 |

| Reverse primer | TTTAACCTTGCGGCCGTACT | 20 | 891 | 872 | 59.96 | 50.00 | |

| Micrococcus luteus(NR_037113.1) | Forward primer | CCACACTGGGACTGAGACAC | 20 | 287 | 306 | 59.97 | 60.00 |

| Reverse primer | GCCCCAAAGGGGAAATCGTA | 20 | 995 | 976 | 60.03 | 55.00 | |

| Bacillus subtilis(AB192294.2) | Forward primer | TAACACGTGGGTAACCTGCC | 20 | 107 | 126 | 59.96 | 55.00 |

| Reverse primer | ATGCACCACCTGTCACTCTG | 20 | 1056 | 1037 | 59.96 | 55.00 |

Antibiotic Sensitivity Test

Antibiotic sensitivity assay for bacterial isolates is a critical step in determining the susceptibility of bacterial or other microorganism isolates to specific antibiotics. The procedure typically involves exposing the isolated microorganisms to different antibiotics under different time periods i.e., 1 to 20 days of incubation and observing their response to identify which drugs are most effective in inhibiting or killing the growth of the isolates.

Disc diffusion assay

Bacterial isolates were tested for antibiotic sensitivity using the Kirby Bauer’s disc diffusion method on Muller-Hinton agar (MHA) with commercially available antibiotic discs. A lawn culture of bacterial suspension was prepared on the MHA plate’s surface using sterile glass spreader. On the surface of the agar plate, antibiotic discs impregnated with antibiotics {Ampicillin (10 mcg), Amoxicillin (25 mcg), Ciprofloxacin (30 mcg), Erythromycin (15 mcg), Metronidazole (5 mcg), Streptomycin (15 mcg), and Tetracycline (30 mcg)} were placed. The discs release the antibiotic into the surrounding agar. The plates were incubated for 16–18 hours at 37oC. The antibiotics were chosen in accordance with NCCLS recommendations. Each antimicrobial agent’s zone diameter was measured after incubation and compared to the NCCLS chart. The zone of inhibition was understood in this way as sensitivity (S), Intermediate (I) or resistant (R).17

Results

Assessment of Microbiological Quality

This study examined the microbiological quality of retail meat in Chandigarh (UT, India) by analyzing Total Aerobic Counts (TAC) and Total Coliform Counts (TCC). The average TAC values of meat samples in this investigation ranged from log10 3.44 CFU/g to log10 3.54 CFU/g. The mean TCC values ranged from log10 2.57 CFU/g to log10 2.75 CFU/g (Table 2). The results indicated that the greatest total aerobic count (TAC) was found in the meat sample from Daddu Majra (log10 3.5 CFU/g), while the lowest TAC (log10 3.44 CFU/g) was recorded in the meat sample from Mani Majra (Table 2). The minimum total coliform count (TCC) was found in the meat sample from Mani Majra (log10 2.54 CFU/g), while the maximum coliform count was recorded in the meat sample from Kaimbwala (log10 2.75 CFU/g) (Table 2).

Table 2: Bacterial counts of raw meat samples from various markets.

| Locations | No of sample | Mean TAC CFU/g | Mean Log10 | Mean TCC CFU/g | Mean Log10 |

| Daddu majra | 9 | 3.19×104 | 3.5 | 5.17×102 | 2.71 |

| Dhanas | 7 | 3.02×103 | 3.48 | 4.32 x102 | 2.63 |

| Hallo majra | 8 | 3.26×103 | 3.51 | 4.92 x102 | 2.69 |

| Kaimbwala | 8 | 3.48×103 | 3.54 | 5.73 x102 | 2.75 |

| Maloya | 10 | 3.09×103 | 3.48 | 3.78 x102 | 2.57 |

| Mani majra | 8 | 2.77×103 | 3.44 | 3.54 x102 | 2.54 |

N: Number of samples; TAC: Total aerobic count; TCC: Total coliform count; CFU/g: Colony forming units per gram

Prevalence and Characterization of Bacteria: Morphological, Biochemical, and Molecular Insights

A total of 50 chicken meat samples were analyzed for the presence of bacterial pathogens. The most frequently isolated bacterial pathogen was Escherichia coli, accounting for approximately 80%. This was followed by Staphylococcus aureus (~ 58%), Salmonella spp. (~35%), Bacillus subtilis (~30%), Micrococcus luteus (~20%), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (~10%) as presented in Table 3. The statistical analysis revealed no significant association between the type of meat and the presence of bacterial pathogens S. aureus, E. coli, Salmonella, Pseudomonas, Bacillus, or Micrococcus (P > 0.05 for all).

This study recorded presence of E. coli in 80% of the samples, surpassing its prevalence in meat samples. The colonies of E. coli exhibited a smooth texture, pink color, circular shape, and slight elevation (Table 4; Figure 1). Additionally, they displayed positive results for the indole test, MR test, nitrate test, and catalase test (Table 5). The 16s rRNA gene amplification and subsequent sequencing of the amplicon revealed that the size of the amplified product was approximately 1000 bp (Figure 2). The 16S rRNA gene sequences of E. coli (isolated) were subsequently aligned with reference nucleotide sequences available on the NCBI using the BLAST tool, thereby confirming the presence of E. coli in the meat samples.

In this study, the prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus was notably high, appearing in ~58% of the samples, making it the second most common bacterium identified. Colonies exhibited a striking golden yellow colour, circular shape, pinhead-sized colonies, smooth edges, and convex elevation (Table 4; Figure 1). Biochemical characterization showed that the MR, VP, citrate, oxidase, nitrate, and catalase tests were positive, which proved that S. aureus was present (Table 5). Furthermore, we successfully amplified and sequenced the 16S rRNA gene from S. aureus, resulting in an amplicon approximately 1000 base pairs in length (Figure 2). After a sequence similarity search using the BLAST tool, confirmed the presence of S. aureus in the meat sample.

Another potential pathogen, Salmonella spp., was detected in approximately ~35% of the total meat samples, making it the third most prevalent bacterium identified in this study. The colonies were characterized by a distinct black centre, slightly red coloration, circular shape, entire margin, and convex elevation (Table 4; Figure 1). Biochemical analysis demonstrated positive results for the MR, citrate, nitrate, and catalase tests, consistent with the characteristics of Salmonella spp. (Table 5). Subsequent molecular analysis involving the amplification and sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene revealed an amplicon of approximately 650 bp (Figure 2). Alignment of the obtained sequences with the reference nucleotide sequences on NCBI using the BLAST tool confirmed the presence of Salmonella spp. in the meat samples.

Bacillus subtilis, another bacterial pathogen found in the meat sample (~30%), formed colonies on tryptone soya agar that exhibited white coloration and were circular, irregular margin, and either flat elevation (Table 4; Figure 1). Biochemical analysis demonstrated positive results for the citrate, oxidase, nitrate, and catalase tests, consistent with the characteristics of Bacillus spp. (Table 5). Subsequent 16S rRNA gene amplification and sequencing, resulted in an amplicon of approximately 1000 bp (Figure 2). To identify regions of local similarity, obtained sequence was compared using the BLAST program to reference nucleotide sequences that are accessible on the NCBI. This alignment provided conclusive evidence of the presence of Bacillus spp. in the meat samples.

In this study, a bacterial infection Micrococcus luteus was found in ~20% of the meat samples. When grown on mannitol salt agar, colonies generally appeared unpigmented or cream-white, with circular, smooth, entire margin, and convex forms (Table 4; Figure 1). Micrococcus luteus tested positive for MR, VP, oxidase, nitrate, and catalase in biochemical tests (Table 5). The 16S rRNA gene from Micrococcus luteus was further amplified and sequenced, producing an amplicon of about 750 bp (Figure 2). The obtained sequence was compared using the BLAST program with reference nucleotide sequences available on NCBI, providing clear evidence that Micrococcus luteus were present in the meat samples.

Through thorough investigation, P. aeruginosa was found in around ~10% of the meat samples exhibited a colorless (opaque) appearance, with a circular shape, irregular margin, and a flat structure colony on centrimide agar (Table 4; Figure 1). Biochemical analysis revealed positive results for the citrate, oxidase, nitrate, and catalase tests, which align with the typical characteristics of P. aeruginosa (Table 5). Following the amplification and sequencing process, a 1000 bp amplicon was successfully obtained from the isolated P. aeruginosa (Figure 2). Aligning the obtained sequences with the reference nucleotide sequences on NCBI using the BLAST tool provided conclusive evidence of the presence of P. aeruginosa in the meat samples.

Table 3: Prevalence of pathogens in raw meat samples

| Locations | No of sample | Prevalence of pathogens (%) | |||||

| E. coli | S. aureus | Salmonella spp. | B. subtilis | M. luteus | P. aeruginosa | ||

| Daddu majra | 9 | 80.23 | 58 | 35.49 | 31.65 | 25.18 | 10.22 |

| Dhanas | 7 | 78.34 | 45.32 | 31.45 | 28.78 | 19.73 | 6.03 |

| Hallo majra | 8 | 82.35 | 56.22 | 32.79 | 24 | 17 | 13.45 |

| Kaimbwala | 8 | 89.45 | 60 | 30.81 | 34.56 | 13.68 | 11.72 |

| Maloya | 10 | 70 | 63.33 | 29.3 | 30.04 | 22.18 | 14 |

| Mani majra | 8 | 68.89 | 59.86 | 35.23 | 29.23 | 23.06 | 9.04 |

Escherichia coli (~80%) followed by Staphylococcus aureus (~60%), Salmonella spp. (~40%), Bacillus subilis. (~35%), Micrococcus luteus (~25%) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (~13%).

Table 4: Morphology of different Bacteria spp. isolated from raw meat sample.

| Bacterial isolates | Colour | Configuration | Margin | Elevations |

| (A) E. coli | Pink Colonies | Circular | Entire | Slightly raised |

| (B) S. aureus | Golden yellow colour | Circular pin head colonies | Entire | Convex |

| (C) Salmonella spp. | Black centre and a slightly red coloured | Circular | Entire | Convex |

| (D) B. subtilis | White | Circular lobate | Irregular | Flat |

| (E) Micrococcus spp. | usually unpigmented or cream white | Circular, smooth | Entire | Convex |

| (F) P. aeruginosa | Opaque colonies | Circular | Irregular (undulated) | Flats |

Table 5: Biochemical test of different Bacterial spp. isolated from raw meat sample.

| TESTS | Bacterial isolates | |||||

| A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| E. coli | S. aureus | Salmonella spp. | B. subtilis | Micrococcus spp. | P. aeruginosa | |

| 1) Indole test | +ve | -ve | -ve | -ve | -ve | -ve |

| 2) MR Test | +ve | +ve | +ve | -ve | +ve | -ve |

| 3) VP Test | -ve | +ve | -ve | -ve | +ve | -ve |

| 4) Citrate test | -ve | +ve | +ve | +ve | -ve | +ve |

| 5) Oxidase test | -ve | +ve | -ve | +ve | +ve | +ve |

| 6) Nitrate reduction test | +ve | +ve | +ve | +ve | +ve | +ve |

| 7) Catalase test | +ve | +ve | +ve | +ve | +ve | +ve |

|

Figure 1: Bacterial isolates from raw meat samples. (A) E. coli, (B) S. aureus, (C) Salmonella spp., (D) B. subtilis, (E) M. luteus, and (F) P. aeruginosa Click here to view Figure |

|

Figure 2: Detection of different bacterial strains in meat sample through amplification of 16S rRNA gene by PCR. Lane M: 1-kb size DNA marker, Lane 1: Amplification of ~938-bp fragment of 16S rRNA gene of E. coli, Lane 2: Amplification of ~917-bp fragment of 16S rRNA gene of S. aureus, Lane Click here to view Figure |

In vitro antimicrobial activity

In an in vitro antibacterial activity test, different bacterial strains were found to have varying sensitivities to different antibiotics. For the disk diffusion test, the presence of clear zone around the antibiotic disk suggesting that the isolates have antibacterial activity which is able to inhibit the growth of the pathogens.

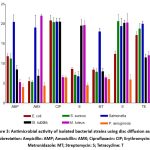

Salmonella spp. exhibited high sensitivity to ampicillin, with significant inhibition zones of 20.45±1.80 mm, while E. coli, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, M. luteus and B. subtilis showed low sensitivity. Salmonella spp. and M. luteus were highly sensitive to amoxicillin, with inhibition zones of 19±3.16 mm and 22±0.40 mm, respectively, but E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, and B. subtilis were less sensitive. E. coli, S. aureus, Salmonella spp., and B. subtilis were highly sensitive to ciprofloxacin, with inhibition zones between 20.4-20.8 mm, whereas P. aeruginosa and M. luteus showed low sensitivity. M. luteus, and B. subtilis. were moderately sensitive to erythromycin, with inhibition zones ~19.5 mm, but E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, and Salmonella spp. showed low sensitivity. Only Salmonella spp. showed high sensitivity to metronidazole with an inhibition zone of 18±0.91 mm; the other bacteria showed low sensitivity. S. aureus, Salmonella, M. luteus, and B. subtilis were highly sensitive to streptomycin, with inhibition zones between 19.37-20.62 mm, while E. coli and P. aeruginosa showed minimal to no sensitivity. E. coli, S. aureus, and Salmonella spp. were highly sensitive to tetracycline, with inhibition zones between 17.12-20 mm, whereas M. luteus and B. subtilis displayed moderate sensitivity and P. aeruginosa showed the least sensitivity (Table 6; Figure 3).

Table 6: Antibiotic sensitivity of different bacteria spp. isolated from raw meat sample.

| Antimicrobial Agent | Symbols | Disc Conc. (mcg) | Bacterial isolates | |||||

| A | B | C | D | E | F | |||

| E. coli | S. aureus | Salmonella spp. | B. subtilis | Micrococcus spp. | P. aeruginosa | |||

| Ampicillin | AMP | 10 | R | R | S | R | R | R |

| Amoxicillin | AMX | 25 | R | R | S | R | S | R |

| Ciprofloxacin | CIP | 30 | S | S | S | S | R | R |

| Erythromycin | E | 15 | R | R | R | I | I | R |

| Metronidazole | MT | 5 | R | R | S | R | R | R |

| Streptomycin | S | 15 | R | S | S | S | S | R |

| Tetracycline | TE | 30 | I | S | S | I | I | R |

S = Sensitive, I = Intermediate, R = Resistant.

|

Figure 3: Antimicrobial activity of isolated bacterial strains using disc diffusion assay.Click here to view Figure |

Abbreviation: Ampicillin: AMP; Amoxicillin: AMX; Ciprofloxacin: CIP; Erythromycin: E; Metronidazole: MT; Streptomycin: S; Tetracycline: T

Discussion

This study employed a cost-effective approach to detect and quantify bacterial microbes in chicken meat sourced from five villages/colonies in Chandigarh city, India. Total Aerobic Counts (TAC) serves as a quality gauge reflecting hygiene condition of the slaughterhouse during processing and aids in evaluating shelf life.18 According to the International Commission on Microbiological Specification for Foods (ICMSF), meat is classified as follows: an acceptable bacterial count is 0-10³ CFU/g, tolerable is 10⁴- 10⁵ CFU/g, and unacceptable is ≥10⁶ CFU/g. A coliform count under 10³ CFU/g poses minimal risk of pathogen transmission to consumers.19 These findings align with a study by Bantawa et al., which reported a higher total aerobic count (log10 8.22 ± 0.14 CFU/g) and total coliform count (8.13 ± 0.13 CFU/g) in retail chicken meat samples.12 In a comparable study conducted by Julqarnain et al. (2022), the bacterial load was maximum of log10 9.04 ± 0.26 CFU/gm, while the minimum was recorded at LBM-4 with log10 8.30 ± 0.54 CFU/gm, at the bird market in Mymensingh City, Bangladesh. The coliform count reached its peak at LBM-2 (log10 6.66 ± 0.80 CFU/gm) and was lowest at LBM-1 (log10 5.53 ± 0.38 CFU/gm).20 It is reasonable to presume that the microbiological community of fresh raw meat in the local market of Daddu Majra is significantly contaminated with spoilage and pathogenic organisms. A statistical analysis did not reveal a significant correlation between the coliform count and the type of meat (P > 0.05).

After microbiological examination of meat sample from Chandigarh (UT, India) revealed the presence of Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella spp., Bacillus subtilis, Micrococcus luteus, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacterial pathogens. This contrasts with an earlier investigation conducted on chicken meat in Nepal, which found that the predominant bacteria isolated included S. aureus (68%), E. coli (54%), Salmonella spp. (34%), P. aeruginosa (40%), and Shigella spp. (6%).12 In a similar study, Jahan and Siddique found that fresh beef samples in Bangladesh were contaminated with Staphylococcus spp. (26.7%), Klebsiella spp. (20%), Enterobacter spp. (10%), and Salmonella spp. (13.3%).21 A study carried out in Nigeria revealed that meat samples were found to contain E. coli (83.6%), S. aureus (96.3%), S. epidermidis (88.8%), Salmonella spp. (42.5%), Pseudomonas spp. (62.5%), and Klebsiella spp. (80%) isolates.22 The higher occurrence of E. coli in meat samples suggests that fecal matter or the conditions of the slaughterhouse environment may have contaminated the meat during the slaughter process. The presence of E. coli serves as a marker for hygiene and sanitation, indicating a risk of foodborne illness to consumers as well as the possibility of other harmful bacteria. The percentage of E. coli isolation and identification varies significantly, possibly due to differences in hygiene levels across various slaughterhouses.23

The occurrence of coagulase-positive S. aureus can be attributed to substandard hygiene practices, which encompass insufficient cleaning, improper handling, contamination after processing, and cross-contamination especially when meat and currency are managed with the same unwashed hands.24 S. aureus is a common pathogen that cause global foodborne illnesses, often linked to improper food handling, especially in meat products. In a study conducted from 2011 to 2016, researchers found that 35% of 1,850 retail meat and meat products in China contained S. aureus. The detection of S. aureus bacterium, despite relatively low contamination levels, underscores the importance of implementing effective food safety measures to avert staphylococcal toxicity.25 Furthermore, 16% of the meat samples sold in Casablanca, Morocco were found to be positive for coagulase positive S. aureus.26 Similar study conducted in Iran, it was found that lamb meat had the highest occurance of S. aureus at 68.8% while beef samples had a prevalence of 57.5% and camel meat had a prevalence of 46.0%.27 A recent study analyzed 139 samples of red meat, meat products, and seafood from various regions in Libya. The findings revealed that 23% of the red meat samples were found to be contaminated with various species of Staphylococci.28

Salmonella spp. is one of the major meat-associated bacterial pathogens responsible for the increased cases of salmonellosis worldwide. A study reported that 21% and 53.3% of the retail meat samples in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam, and Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, respectively, were contaminated with Salmonella spp.29 Salmonella spp. was detected in 11.4% (14/123) of the meat samples. Out of the eight chicken samples, 14.5% tested positive for Salmonella. Similarly, five buffalo samples (13.5%) and one goat sample (3.3%) also showed positive results for Salmonella. The prevalence of Salmonella was found to be 3.3% for S. pullorum, 0.8% for S. gallinarum, 1.6% for S. typhi, 0.8% for S. choleraesuis, and 4.9% for Salmonella of subgenus I or II group.30 In another study, Salmonella spp. counts between log10 1.3 CFU/g and log10 2.67 CFU/g in chicken meat at super shops in Dhaka, Bangladesh.31 The contamination rate is often affected by climate and temperature conditions during food storage. European and northern Asian countries generally experience lower contamination rates due to their temperate climates. Conversely, tropical regions with higher average temperatures face increased risks of Salmonella spp. contamination. Discrepancies in prevalence rates between studies may stem from unsanitary processing practices and inadequate sanitation in meat shops. This underscores the lack of awareness among meat retailers regarding fundamental hygiene standards and guidelines for handling meat.

Bacillus cereus is a pathogen associated with food that has the potential to induce food poisoning. Foods derived from animals, such as meat and meat products, play a crucial role in the diet. Therefore, the contamination and proliferation of B. cereus in raw meat and its products raise significant concerns regarding public health risks.32 In another study of 1,963 samples from Japan, B. cereus was present in 6.6% of raw meat samples and 18.3% of meat product samples.33 A previous study by Tewari et al. 2015 reported that 29 out of the 94 samples analyzed tested positive for B. cereus, accounting for 30.9% of the total. In raw meat samples, the incidence was 27.8%, whereas in meat products, it reached 35%. Interestingly, the contamination rate was higher in cooked meat samples (35%) compared to raw meat samples (27.78%) out of the 40 cooked meat products and 54 raw meat samples that were tested.32

Micrococcus luteus is a gram-negative bacterium found in fresh meat that can spoil the food quality. The Micrococcus species is responsible for the red color of fermented sausage. During fermentation, Micrococcaceae produce the enzyme nitrate reductase, which catalyzes the conversion of added nitrate to nitrite and eventually to nitric oxide. The nitric oxide then reacts with myoglobin to give the desired red color of the product.34 In this study, 25% of samples have shown presence of M. luteus. A study of 68 traditionally prepared meat samples from India found 284 micrococcaceae at a level of 105-107 CFU/g.35 Another study of beef samples from Opolo Market found that M. luteus was the most common bacteria isolate, occurring in 55% of samples.36

Pseudomonas spp., a group of bacteria well-known for their role in food spoilage. Pseudomonas spp. are particularly prevalent in chicken, where they thrive as part of the natural microbiota.37,38 These psychrotrophic bacteria can easily proliferate in foods stored under aerobic conditions and at low temperatures, making them common contaminants in meat, fish, milk, and dairy products.39 Out of 320 meat samples tested, 69 were found to be contaminated with various species of Pseudomonas, including P. lundensis, P. fragi, P. oryzihabitans, P. stutzeri, P. fluorescens, P. putida, and P. aeruginosa.40 In this study, the presence of these bacteria can often be traced back to poor sanitation practices in meat shops, unhygienic processing methods, and a lack of awareness among meat retailers about basic hygiene requirements and guidelines for maintaining meat safety.12 In the current investigation, inadequate sanitation procedures frequently seen in nearby meat stores are responsible for the presence of these bacterial contamination. Microbial contamination is largely caused by factors including unsanitary slaughtering and processing practices, improper equipment and surface cleaning, and inadequate personal hygiene among meat workers. Furthermore, the lack of awareness among meat retailers about standard hygiene protocols and food safety regulations intensifies the problem, underscoring the critical necessity for training initiatives and more stringent regulatory enforcement to guarantee the safety of meat products.

Conclusion

In this study, the meticulous isolation and screening of bacterial strains in meat samples collected from various areas in Chandigarh reveal a concerning level of bacterial contamination. E. coli was detected in 80% of the samples, followed by S. aureus in ~58%, Salmonella spp. in around ~35%, Bacillus subtilis in ~30%, Micrococcus luteus in ~20%, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in ~10%. The lowest mean values for total aerobic count (TAC) and total coliform count (TCC) were log10 3.44 CFU/g and log10 2.57 CFU/g, respectively. This research emphasizes the pivotal role bacteria play in foodborne diseases and antibiotic resistance, paving the way for deeper investigation and potential public health applications of these resilient strains. Markets showed high contamination levels and diverse bacterial populations, likely due to varying hygienic practices among retailers. To address this issue, stringent sanitary and hygienic practices must be adopted in broiler slaughterhouses. Our findings highlight the need for routine monitoring of meat shops, strict enforcement of the Animal Slaughter and Meat Inspection Act 2055 (1999, India), and awareness campaigns for butchers and consumers to ensure better meat quality and safety.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thanks GGDSD college and SGGS college to perform the research work. The authors extend their heartfelt gratitude to co-authors who contributed, directly or indirectly, to the successful completion of this research.

Funding Sources

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

This statement does not apply to this article.

Ethics Statement

This research did not involve human participants, animal subjects, or any material that requires ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not involve human participants, and therefore, informed consent was not required.

Clinical Trial Registration

This research does not involve any clinical trials.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

Not Applicable

Author Contributions

Vikas Kushwaha: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Analysis, Writing

Anuprabha: Methodology, Writing- Reviewing & Editing

Varruchi Shamra: Writing, Data Collection

References

- Osemwowa E., Omoruyi I. M., Kurittu P., et al. Bacterial quality and safety of raw beef: A comparison between Finland and Nigeria. Food Microbiol. 2021; 100:103860.

CrossRef - Leroy F., Smith N. W., Adesogan A. T., et al. The role of meat in the human diet: evolutionary aspects and nutritional value. Anim Front. 2023;13(2):11-18.

CrossRef - Rani Z. T., Mhlongo L. C., Hugo A. Microbial Profiles of Meat at Different Stages of the Distribution Chain from the Abattoir to Retail Outlets. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(3):1986.

CrossRef - Baah D. A., Kotey F. C. N., Dayie N. T. K. D, et al. Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria Contaminating Raw Meat Sold in Accra, Ghana. Pathogens. 2022;11(12):1517.

CrossRef - Didier P., Nguyen-The C., Martens L., et al. Washing hands and risk of cross-contamination during chicken preparation among domestic practitioners in five European countries. Food Control. 2021;108062.

CrossRef - Tesson V., Federighi M., Cummins E. et al. A Systematic Review of Beef Meat Quantitative Microbial Risk Assessment Models. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020;17(3):688.

CrossRef - Food safety. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/food-safety#tab=tab_1 (Accessed on 22 Oct 2024).

- EFSA (2019) The European Union One Health 2018 Zoonoses Report | EFSA. Available from: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/pub/5926 . Accessed 5 Aug 2024).

- Ali S., Alsayeqh A. F. Review of major meat-borne zoonotic bacterial pathogens. Public Health. 2022;10:1045599.

CrossRef - Diyantoro, Wardhana D. K. Risk Factors for Bacterial Contamination of Bovine Meat during Slaughter in Ten Indonesian Abattoirs. Vet Med Int 2019;2019:2707064.

CrossRef - Bigwood T., Hudson J. A., Billington C., et al. Phage inactivation of foodborne pathogens on cooked and raw meat. Food Microbiol. 2008;25(2):400-406.

CrossRef - Bantawa K., Rai K., Subba Limbu D., Khanal H. Food-borne bacterial pathogens in marketed raw meat of Dharan, eastern Nepal. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):618.

CrossRef - Coico R. (2006) Gram StainingCurr Protoc Microbiol 00:A.3C.1-A.3C.2.

CrossRef - Cappuccino J. G., Sherman N. Microbiology: A Laboratory Manual. Benjamin Cummings. 2011. pp 544.

- Bhumbla U. Identification of Bacteria by Biochemical Reactions. In: Workbook for Practical Microbiology. India: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd; 2018. pp 84–100.

CrossRef - Teng F., Darveekaran Nair S. S., Zhu P., et al. Impact of DNA extraction method and targeted 16S-rRNA hypervariable region on oral microbiota profiling. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):16321.

CrossRef - Raj Y., Singh V., Chauhan A. Isolation, characterization and screening of novel antibiotic producing bacteria from natural habitats of Western Himalayas and industrial waste soil samples. J. Chem. Stud. 2019;7(3): 3282-3288.

- Issa-Zacharia A., Seif M. Evaluation of Hygienic Practices and Microbiological Quality of Street Vended Fruit Salads in Morogoro, Tanzania. European j. nutr. food saf. 2023;15:73–84.

CrossRef - Swanson K. M. J., Buchanan R. L., Cole M. B., et al. Microorganisms in Foods 8: Use of Data for Assessing Process Control and Product Acceptance. New York: Springer; 2011.

- Julqarnain S., Bose P., Rahman M., et al. Bacteriological quality and prevalence of foodborne bacteria in broiler meat sold at live bird markets at Mymensingh City in Bangladesh. J Adv Vet Anim Res. 2022;9:405–11.

CrossRef - Jahan F., Mahbub-E-Elahi A. T. M., Siddique A. B. Bacteriological Quality Assessment of Raw Beef Sold in Sylhet Sadar. The Agriculturists. 2015;13(2):9–16.

CrossRef - Obande G. Bacteriological quality of fresh raw beef and chevon retailed in lafia metropolis, nigeria. Microbiol. Res. 2016;6:29–34..

- Lee J., Han D., Lee H. T., et al. Pathogenic and phylogenetic characteristics of non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolates from retail meats in South Korea. Vet. Sci. 2017;19(2):251-259.

CrossRef - Adegunloye D. Microbial composition of the abattoir environment and its health implications on the quality of fresh cow meat sold in Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria. WIT Press, UK. 2013; 170:57-65.

CrossRef - Wu S., Huang J., Wu Q., et al. Staphylococcus aureus isolated from retail meat and meat products in China: Incidence, Antibiotic Resistance and Genetic Diversity. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2767.

CrossRef - Cohen N., Ennaji H., Hassar M., et al. The bacterial quality of red meat and offal in Casablanca (Morocco). Nutr. Food Res. 2006;50:557–562.

CrossRef - Rahimi E., Nonahal F., Salehi E. Detection of Classical Enterotoxins of Staphylococcus aureus Strains Isolated From Raw Meat in Esfahan, Iran. Health Scope. 2013;2:95–98.

CrossRef - Naas H., Edarhoby R., Garbaj A., et al. Occurrence, characterization, and antibiogram of Staphylococcus aureus in meat, meat products, and some seafood from Libyan retail markets. World. 2019;12:925-931.

CrossRef - Van T. T. H., Moutafis G., Istivan T., et al. Detection of Salmonella spp. in Retail Raw Food Samples from Vietnam and Characterization of Their Antibiotic Resistance. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(21):6885-6890.

CrossRef - Maharjan M., Joshi V., Joshi R., et al. Prevalence of Salmonella Species in Various Raw Meat Samples of a Local Market in Kathmandu. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006;1081:249–256.

CrossRef - Uddin Q., Parveen N., Khan N. U., et al. Antifilarial potential of the fruits and leaves extracts of Pongamia pinnata on cattle filarial parasite Setaria cervi. Phytother Res. 2003;17(9):1104-1107.

CrossRef - Tewari A., Singh S. P., Singh R. Incidence and enterotoxigenic profile of Bacillus cereus in meat and meat products of Uttarakhand, India. J Food Sci Technol. 2015;52(3):1796–1801.

CrossRef - Konuma H, Shinagawa K., Tokumaru M., et al. Occurrence of Bacillus cereus in Meat Products, Raw Meat and Meat Product Additives. J Food Prot. 1988;51:324-326.

CrossRef - Zakpaa H., Imbeah C., Mak-Mensah E. Microbial characterization of fermented meat products on some selected markets in the Kumasi metropolis, Ghana. J. Food Sci. 2009;3:340-346.

- Nkanga E., Uraih N. Prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus in Meat Samples from Traditional Markets in Benin City, Nigeria and Possible Control by Use of Condiments. J. Food Prot. 1981;44:4-8.

CrossRef - Oku I., Oyadougha T. Microbial Examination of Bacteria Isolated from Raw Beef Samples Sold in Opolo Market, Yenagoa Metropolis, Bayelsa State, Nigeria. Appl. Sci. Envir. Manag. 2023;27:2009-2014.

CrossRef - Mellor G. E., Bentley J. A., Dykes G. A. Evidence for a role of biosurfactants produced by Pseudomonas fluorescens in the spoilage of fresh aerobically stored chicken meat. Food Microbiol. 2011;28:1101-1104.

CrossRef - Marchand S., Block J., Jonghe V., et al. Biofilm Formation in Milk Production and Processing Environments; Influence on Milk Quality and Safety. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2012;11:133-147.

CrossRef - Remenant B., Jaffrès E., Xavier D., et al. Bacterial spoilers of food: Behavior, fitness and functional properties. Food microbial. 2015;45:45–53.

CrossRef - Elbehiry A., Marzouk E., Moussa I., et al. Pseudomonas Species Prevalence, Protein Analysis, and Antibiotic Resistance: An Evolving Public Health Challenge Health Protection Agency (2009) Guidelines for Assessing the Microbiological Safety of Ready-to-Eat Foods Placed on the Market. UK: HPA; 2021.

CrossRef

Abbreviations

ml: millilitre; min: minute; rpm: rotation per minute; N: Number of samples; TAC: Total aerobic count; TCC: Total coliform count; CFU/g: Colony forming units per gram; MR: Methyl red; VP: Voges Proskauer; mol/L: mol per litre; S: MHA: Muller-Hinton agar; Sensitive, I: Intermediate, R: Resistant; Ampicillin: AMP; Amoxicillin: AMX; Ciprofloxacin: CIP; Erythromycin: E; Metronidazole: MT; Streptomycin: S; Tetracycline: T

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.