Manuscript accepted on : 11-03-2025

Published online on: 23-06-2025

Plagiarism Check: Yes

Reviewed by: Dr. Meryem Aydemir Atasever

Second Review by: Dr. Wan Zawiah Wan Abdullah

Final Approval by: Dr. Hesham Ali El Enshasy

Kouame Ally Stephane*, Zhu Simining, He Hongyuan and Zhang Lufang

School of Food Science and Engineering, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou,China

Corresponding Author Email: kouameally@gmail.com

DOI : http://dx.doi.org/10.13005/bbra/3384

ABSTRACT: Cellulose is a natural polymer with unique physical and chemical properties, making it widely used in the food industry as an emulsifier, thickener, and stabilizer. Its abundance, biodegradability and non-toxicity make it a preferred material and further enhance its appeal. However, extracting cellulose from plant sources remains a challenging due to the complex structure of plant cell walls. This study focuses on optimizing the extraction of cellulose from pistachio kernel and characterizing its physicochemical properties using response surface methodology (RSM). The extraction process involved alkaline treatment with sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution to remove the hemicelluloses and lignin from the pistachio kernel while leaving the cellulose intact and bleaching with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). The effects of key factors - solid-liquid ratio, pH, alkaline treatment time, and reaction temperature were evaluated. The results showed that increasing the alkaline treatment time enhanced cellulose yield, reaching 38.6% - 39.48% between 60min-150min. However, excessive temperature and H2O2 dosage led to reduced cellulose extracted from the Asian pistachio kernel. As a result of the optimization through RSM regression analysis (R2 = 0.98, p = 0.05) identified the optimal extraction conditions as 1.0mL of H2O2, 75.58min alkali treatment time and a reaction temperature is 53.10°C, yielding a maximum of 40.0315%. Compare to conventional extraction

KEYWORDS: Cellulose; Extraction; Optimization; Pistachio Kernels; Response surface analysis; Yield Analysis

Download this article as:| Copy the following to cite this article: Stephane K. A, Simining Z, Hongyuan H, Lufang Z. Optimization of Pistachio Kernel Cellulose Extraction using Response Surface Methodology: Effects of Key Processing Factors. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(2). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Stephane K. A, Simining Z, Hongyuan H, Lufang Z. Optimization of Pistachio Kernel Cellulose Extraction using Response Surface Methodology: Effects of Key Processing Factors. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(2). Available from: https://bit.ly/45Bjjs2 |

Introduction

Asian pistachio (Pistacia vera L.) is a popular nut crop known for its unique flavor, high nutritional value, and health benefits,1 which constitutes about 50% of the weight of the nut.2 It is native to West Asia, especially in northeastern Iran and northern Afghanistan, where the pistachio tree formed an important part of the local semi-arid aromatic forest.3,4 According to a survey, the United States produces 47 % of the pistachio, followed by Iran (38%) and turkey (9%) in the world market.5 Asian pistachio kernel also contains several bioactive compounds,6 such as polyphenols, tocopherols and phytosterols popularly known for their beneficial health effects.2 Polyphenols are known for their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, while tocopherols are important antioxidants that can protect against oxidative stress.7 The phenolic compounds and the oxidizing activity of pistachio decrease with an increase in the ripening period. The core of Asian pistachio (Pistacia vera L.) is made up of protein of 15.0 – 21.2%8,9 fats of 55.2 – 60.5%,10 carbohydrates

14.9 – 17.7%11 moisture of 2.5 – 1%,12 ash of 2.2 – 2.5%,12 13 phenolic compounds13 and fiber.14,15 The fiber content varies from 4.8% to 10.6% and makes it a potential source of cellulose.16 Cellulose, being the most abundant raw material on earth, is produced commercially through several plants every year because of its substantial involvement in a variety of potential applications. It can be used in the paper, textile, and food industries along with its utilization in pharmaceutical and biomedical applications.17 because of its several health benefits, which include reducing the risk of chronic diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and colon cancer.18 Cellulose is referred to as a non-toxic major constituent of plant material that can be extracted from higher plants like wood, cotton, flax, hemp, jute, sugarcane bagasse, ramie, cereal straws, etc.19 It is said to be renewable and acts as a polysaccharide filler.20 It is the most abundant biopolymer in the world, with an estimated 1010–1012 tons produced annually, and primarily consists of lingo-cellulose which includes cellulose, lignin, and hemicellulose.21 Lignin is a highly cross-linked phenolic polymer, while hemicellulose is a branched multiple polysaccharide polymer.19 Lignin and hemicellulose are removed by treating raw matter with alkali and a bleaching agent.22 This study focuses on the study of the extraction of cellulose fibers from the pistachio kernel using response surface methodology.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Design

Materials and Chemicals

Asian pistachio kernel was purchased from Guangzhou Nanxing Tianhong Company, China, sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and 30% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) were purchased from Fuchen (Tianjin) Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., China, and Guangdong Qianhui Reagent Company, China, respectively. The chemicals were analytically graded and purified before purchase. Hence, chemicals were used without further purification.

Apparatus and Equipment’s

A constant temperature heating magnetic stirrer (DF-101S) was purchased from Gongyi Yuhua Instrument Co., Ltd. China, centrifuge (TGL-16MC), was purchased from Changsha Xiangrui Centrifuge Co., Ltd. China, Electronic analytical balance (OP224C), was purchased from Ohaus Instruments (Changzhou) Co., Ltd. China, grinder (XS-04) was purchased from Shanghai Zhaoshen Technology Co., Ltd. China, pH meter (SJ-3F), was purchased from Shanghai Precision Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd. China, Electric blast drying oven (PH050A), was purchased from Shanghai Yiheng Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd. China’s dual-function steam bath Constant Temperature Oscillator (ZD-85) was purchased from Changzhou Enpei Instrument Manufacturing Co., Ltd. China was gotten at the South China University of Technology Food Chemistry Laboratory.

Experimental Methods

Pistachio Kernel Pre-treatment

The pistachio kernels were dried, crushed into 40mm with a shredder, and then the pistachios were soaked in ethanol with a solid-liquid ratio of 1:10, with a reaction of 120 min, at 150 rpm and 50oC in a steam bath constant temperature oscillator. After the process, it was then dried to a constant weight.

Extraction process of Cellulose from Pistachio kernel

At the ratio of 1:20, 5 g of pistachio kernel was added to the sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution with a pH of 10; it was then mixed thoroughly and placed in a constant temperature magnetic stirrer and processed at a speed of 20 rpm/min at 50oC for 60 mins. 0.5 mL of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was then added at a constant reaction for about 30 mins at the same time and speed. After a complete reaction, centrifugation was done at 6000 rpm, then the precipitate (M) was washed repeatedly with ultra-pure water until the supernatant was neutral, then was placed in the oven at 50oC to dry to constant weight. The weight (m) measurement was then calculated to confirm the yield of cellulose.

Calculating Cellulose yield from Pistachio kernel

Where ‘m’ is the initial mass

M is the precipitate after extraction

Optimization of Response Surface Methodology for extracting Cellulose from Pistachio Kernels. Taking the amount of hydrogen peroxide, reaction time, and reaction temperature as the main factors affecting the extraction of cellulose from pistachio nuts, and taking the yield of cellulose as the response value, a three-factor, three-level response surface experiment was carried out to determine the optimal process as shown in the table below.

Table 1: Response surface factors and level design

| coding level | |||

| variable | |||

| -1 | 0 | 1 | |

| A: The amount of hydrogen peroxide (mL) | 1 | ||

| 0 | 0.5 | ||

| B: Alkali treatment time | 30 | 60 | 90 |

| C: Reaction temperature | 40 | 50 | 60 |

Results

Single factor experiments of cellulose extraction from pistachio kernels

Effect of Solid to Liquid ratio on Cellulose yield

The solid-to-liquid ratio significantly influenced cellulose yield from pistachio kernels as depicted in Figure 1. Increasing the volume of the alkaline solution led to a decline in cellulose yield, primarily due to excessive dilution of NaOH, reducing its effectiveness in the degradation of non-cellulosic components. A balanced solid-liquid ratio ensures that the alkaline solution sufficiently penetrates the cell structure to remove lignin and hemicellulose while minimizing excessive cellulose loss.

|

Figure 1: Effect of solid-liquid ratio on cellulose yield of pistachio kernels |

Effect of pH on cellulose yield

As illustrated in Figure 2, the pH of the extraction solution significantly influenced cellulose yield. The yield exhibited a declining trend with increasing pH values. Excessively high pH levels increased alkalinity, leading to the breakdown of hemicellulose and lignin, thereby compromising cellulose integrity. The results showed that an increase in pH beyond 8.0 led to a decline in cellulose recovery, indicating excessive alkalinity contribute to cellulose degradation. A pH around 8.0 was found to be optimal for lignin and hemicellulose removal while preserving cellulose integrity.

|

Figure 2: Effect of pH on the cellulose yield of pistachio kernels |

Effect of alkali treatment time on cellulose yield

As illustrated in Figure 3, extending the alkali treatment time initially led to an increase in cellulose yield, peaking at 39.48% at 150 minutes. However, beyond 60 minutes, the rate of increase slowed, indicating that prolonged exposure of NaOH begins to degrade the cellulose structure rather than improving its purity. These findings indicate that alkali treatment duration of approximately 60 minutes is sufficient to extract most of the pistachio kernel fiber while minimizing excessive degradation.

|

Figure 3: Effect of alkali treatment time on the cellulose yield of pistachio kernels |

Effect of the amount of hydrogen peroxide on the yield of cellulose

The impact of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) dosage on cellulose yield is shown in Figure 4. The data revealed that a moderate H2O2 dosage (0.5 mL) led to optimal cellulose yield, while higher concentration resulted in reduced recovery. This trend is attributed to oxidative degradation, where excessive H2O2 breakdown cellulose along with lihnin and hemicellulose.

|

Figure 4: Effect of 30% H2O2 dosage on the cellulose yield of pistachio kernels |

Effect of reaction temperature on cellulose yield

Reaction temperature had a profound effect on cellulose extyraction (Figure 5). Increasing the temperature from 40°C to 50°C improved cellulose extraction due to enhanced NaOH penetration and lignin breakdown. However, temperatures exceeding 50°C resulted in decreased yield, likely due to thermal degradation of cellulose. The results suggest that an optimal extraction temperature of approximately 50°C maximizes cellulose recovery while preventing degradation.

|

Figure 5: Effect of Temperature on the cellulose yield of pistachio kernels |

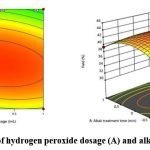

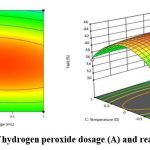

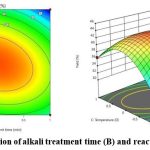

Response surface analysis and optimization of pistachio kernel cellulose extraction Analysis of interaction

Contour plots and response surface plots shows the significance of the interaction between the factors. The contour map tends to be elliptical, the angle between the axis and the coordinate axis is large, and the color changes are rich. Hence, the result indicated that all interaction is significant. Figures 6, 7, and 8 illustrate the response surface plots, which reveal the interactions among hydrogen peroxide dosage, alkali treatment time, and reaction temperature. The elliptical contour plots indicate significant interactions between these factors. Notably, the interaction between alkali treatment time and reaction temperature was found to be the most influential in determining cellulose yield. Optimizing the RSM regression analysis (R2 = 0.98, p < 0.05) identified the optimal conditions as follows: hydrogen peroxide dosage of 1.0 mL, alkali treatment time of 75.58 minutes, and reaction temperature of 53.10°C. Under these conditions, the maximum cellulose yield was predicted to be 40.03%, as confirmed by experimental validation (Figure 9).

|

Figure 6: Interaction of hydrogen peroxide dosage (A) and alkali treatment time (B) |

|

Figure 7: Interaction of hydrogen peroxide dosage (A) and reaction temperature (C) |

|

Figure 8: Interaction of alkali treatment time (B) and reaction temperature (C) |

|

Figure 9: Optimum process conditions |

Discussions

The results show that an increased volume of alkaline solution led to a decrease in cellulose yield (Figure 1). Excessive solvent dilution reduced NaOH efficiency in breaking down non-cellulosic components, leading to lower cellulose recovery. This observation aligns with previous studies, such as those by,20 which reported that excessive solvent use dilutes the reactive agents, reducing their efficiency in breaking down non-cellulosic components. A balanced ratio ensures optimal lignin and hemicellulose removal while minimizing cellulose degradation, similar to findings reported by [10] on lignocellulosic biomass extraction. The optimal solid-liquid ratio was found to balance cellulose yield while minimizing excessive alkali degradation, as supported by studies on cellulose extraction from other plant-based materials.21 As depicted in Figure 2, pH critically affected cellulose yield. Maintaining a pH around 8.0 facilitated effective lignin removal while preserving cellulose integrity. The pH of the extraction medium significantly influenced the cellulose yield (Figure 2). Previous studies, including those by13 and,14 confirm that maintaining the pH at an optimal level prevents excessive degradation and preserves cellulose structure. The results suggest that maintaining the pH at approximately 8 is optimal for minimizing cellulose loss while ensuring effective lignin and hemicellulose removal.

Alkali treatment time strongly impacted cellulose yield (Figure 3), with peak recovery at 150 minutes, but degradation effects were observed beyond 60 minutes. Extended exposure to NaOH can weaken cellulose structure, as seen in studies on corn husk extraction20 and agricultural residues.23 These findings highlight the importance of controlling treatment time to optimize cellulose extraction. Similar findings were reported by,22 who demonstrated that extending alkali treatment beyond optimal durations could lead to cellulose breakdown due to prolonged exposure to harsh chemical conditions. Hydrogen peroxide dosage significantly influenced cellulose yield, as shown in Figure 4. While moderate H₂O₂ (0.5 mL) improved delignification, excessive concentrations reduced cellulose recovery due to oxidative degradation. This reaction leads to excessive removal of lignin and hemicellulose, thereby diminishing the cellulose content24 observed a similar trend in cellulose extraction from biomass sources, emphasizing the delicate balance required in H2O2 dosage to optimize yield. Similar trends were reported in biomass delignification studies by,25 emphasizing the need for precise H₂O₂ control to prevent structural breakdown.

The effect of reaction temperature is evident in Figure 5, where initial increasing temperature from 40°C to 50°C improved cellulose extraction due to enhanced NaOH penetration and lignin breakdown. However, temperatures exceeding 50°C resulted in decreased yield, likely due to thermal degradation of cellulose,19-26 noted that excessive heat exposure could disrupt cellulose chains, reducing overall recovery rates. The results suggest that an optimal extraction temperature of approximately 50°C maximizes cellulose recovery while preventing degradation.27,28 Response surface analysis (Figures 6–8) demonstrated significant interactions between H₂O₂ dosage, alkali treatment time, and reaction temperature. The regression analysis (R² = 0.98, p < 0.05) confirmed that optimized conditions (1.0 mL H₂O₂, 75.58 min alkali treatment, and 53.10°C temperature) resulted in a 40.03% cellulose yield (Figure 9). Notably, the interaction between alkali treatment time and reaction temperature was found to be the most influential in determining cellulose yield which is in consistency the previous study by29,30 similarly reported that optimization of these parameters significantly enhanced cellulose extraction efficiency from plant biomass. These findings align with cellulose optimization studies on pistachio shells8,31 and plant biomass.32

The obtained cellulose yield of 40.03% aligns with previous studies on cellulose extraction from pistachio shells and other plant-based sources32 reported a similar cellulose yield of approximately 38% using ultrasound-assisted extraction, while24 highlighted the efficacy of alkaline treatment in enhancing cellulose recovery. Moreover, the observed interactions among extraction parameters corroborate findings by,22 emphasizing the critical role of process optimization in maximizing cellulose yield. Additionally,21 demonstrated that various extraction methodologies, including acid hydrolysis, could yield similar or higher cellulose recovery rates, though often with additional processing constraints.

While the optimized conditions yielded high-quality cellulose, limitations exist in the methodology. The study relied on laboratory-scale extraction, which may not fully capture industrial-scale variations in raw material composition and processing efficiency. Additionally, the absence of enzymatic or solvent-based comparative analyses limits the understanding of alternative extraction approaches. The extracted cellulose exhibited high purity and thermal stability, making it suitable for food applications such as stabilizers and emulsifiers. Additionally, its biodegradability and non- toxicity position it as a sustainable alternative to conventional cellulose sources. Future studies should focus on scaling up extraction processes, further characterizing the cellulose properties, and exploring applications in biodegradable materials, pharmaceuticals, and food industries.

Conclusion

The study successfully optimized the extraction of cellulose from pistachio kernels using response surface methodology. Key process parameters, including alkali treatment time, hydrogen peroxide dosage, and reaction temperature, significantly influenced cellulose yield. Cellulose was extracted from pistachio kernel through the alkaline method using sodium hydroxide and 30% hydrogen peroxide. Factors such as solid-liquid ratio, pH, and alkaline treatment time determined the yield of cellulose. Response surface methodology was used in this experiment to confirm the significant interaction between the factors such as hydrogen peroxide dosage, alkali treatment time and temperature. The optimized conditions resulted in a maximum yield of 40.03%, demonstrating the feasibility of pistachio kernel cellulose as a sustainable and high-quality source for industrial applications. Beyond its laboratory feasibility, the extracted cellulose holds promising industrial and environmental applications. Given its high purity and biodegradability, pistachio kernel-derived cellulose can be utilized in biodegradable packaging, pharmaceutical formulations, food stabilizers, and bio-based composites, reducing dependence on synthetic polymers and enhancing sustainability in material science. Furthermore, its renewable nature aligns with global efforts to promote eco- friendly alternatives in cellulose-based industries. Future research should focus on scaling up the extraction process and evaluating the physicochemical properties of the extracted cellulose in diverse applications, including functional biomaterials and environmental sustainability efforts and green industrial practices.

Acknowledgment

I thank the staff of the School of Food Science and Engineering at South China University of Technology (SCUT) for their dedication to education, as well as the Food Science and Engineering Campus for their commitment to excellence. I will be eternally grateful for the knowledge and skills acquired at South China University of Technology and look forward to putting them to good use in my future endeavors.

Funding Sources

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

This statement does not apply to this article.

Ethics Statement

This research did not involve human participants, animal subjects, or any material that requires ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not involve human participants, and therefore, informed consent was not required.

Clinical Trial Registration

This research does not involve any clinical trials.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

Not Applicable

Author Contributions

Kouame Ally Stephane: Conceptualization, Visualization, Validation, Data acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Zhu Siming: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

He Hongyuan: Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Zhang Lufang: Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition

References

- Chatrabnous N, Yazdani N, Vahdati Determination of nutritional value and oxidative stability of fresh walnut: [J]. Journal of Nuts 2018, 9(1): 11-20.

CrossRef - Zarei M, Barzegar M, Sahari A et al. Extraction and characterization of oil from pistachio (Pistacia vera l.) kernel by supercritical carbondioxide and solvent extraction: [J]. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 2017, 54(3): 582-590.

- Zohary D, Hopf M, Weiss Domestication of plants in the old world: the origin and spread of domesticated plants in Southwest Asia, Europe, and the Mediterranean Basin: Oxford University Press 2012, 243-250

- Esteki M, Ahmadi P, Vander H, et Fatty Acids-Based Quality Index to Differentiate Worldwide Commercial Pistachio Cultivars: [J]. Journal of Molecules, 2019, 24(1):58-65.

CrossRef - Manirul S.K. Extraction and Characterization of Oil from Pistachio Nutshell: [J]. Journal of Mexican Chemical Society, 2021, 65: 3-8.

CrossRef - Syed A, Mueen A, Sania Z, et An appealing review of industrial and nutraceutical applications of pistachio waste: [J]. Journal of Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 2022, 10: 83-98.

- Asgary S, Parkhideh S, Solhpou A, et al. Improvement of hypertension, endothelial function a nd systemic inflammation following short-term supplementation with red beet (Beta vulgaris L.) juice: a randomized crossover pilot study: [J]. Journal of human hypertension, 2011, 25(3): 165- 169.

- Corsi, , Mateo, S., Spaccini, F. et al. Optimization of Microwave-Assisted Organosolv Pretreatment for Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Cherry Tree Pruning and Pistachio Shells: a Step to Bioethanol Production. Bioenerg. Res. 17, 294–308 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12155-023-10647-x

CrossRef - Moreno-Rojas, J. M., Velasco-Ruiz, I., Lovera, M., Ordoñez-Díaz, J. L., Ortiz-Somovilla, V., De Santiago, E., Arquero, O., & Pereira-Caro, G. (2022). Evaluation of Phenolic Profile and Antioxidant Activity of Eleven Pistachio Cultivars (Pistacia vera L.) Cultivated in Andalusia. Antioxidants, 11(4), 609. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11040609.

CrossRef

- Zhang, , et al., Lignocellulose pretreatment by Deep eutectic solvent and water binary system for enhancement of lignin extraction and cellulose saccharification. Industrial Crops and Products, 2024. 211: p. 118257.

CrossRef - Mollaei S, Nazoori Impact of pistachio nuts consumption on human health: [J]. Journal of Pistachio and Health, 2019, 2(4): 16-26

- Alasalvar C and Shahidi Tree nuts: Composition, phytochemicals, and health effects: An overview. CRC press, Boca Raton, 2008,15-24.

- Kelebek H, Sonmezdag A, Guclu G, et Comparison of phenolic profile and some physicochemical properties of Uzun pistachios as influenced by different harvest period: [J]. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation, 2020, 44(8): 14-20.

CrossRef - Dreher, L. Pistachio nuts: Composition and potential health benefits: [J]. Journal of Nutritional Review, 2012, 70: 234–240.

CrossRef

- Ahmed, Z.B., Yousfi, , Viaene, J., Dejaegher, B., Demeyer, K. and Vander Heyden, Y., 2021. Four Pistacia atlantica subspecies (atlantica, cabulica, kurdica and mutica): A review of their botany, ethnobotany, phytochemistry and pharmacology. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 265, p.113329.

- Seyedi, S, Nasirpour A, Khodaei A et Ultrasound-assisted extraction of cellulose from pistachio shells: [J]. Journal of Carbohydrate Polymers, 2015, 126: 91-98.

- Khan R, Jolly R, Fatima T, Shakir M. (2022) Extraction processes for deriving cellulose: A comprehensive review on green Polym Adv Technol. 33(7): 2069-2090. doi:10.1002/pat.5678

CrossRef - Slavin Pistachio nuts: composition and potential health benefits: [J]. Journal of Nutrition 303 Today, 2013, 48(2): 60-64.

CrossRef - Mounika Movva and RavindraKommineni. Extraction of cellulose from pistachio shell and physical and mechanical characterisation of cellulose-based nanocomposites: [J]. Journal of Material Research Express, 2017, 4: 1-8.

CrossRef - Gopinath R, Ganesan K, Saravanakumar S et al. Characterization of new cellulosic fiber from the stem of Sida rhombifolia: [J].Journal of Polymer Analysis Characterization, 2016, 21: 123–129.

CrossRef - Josh Marett, Alex Aning, Johan Foster. The isolation of cellulose nanocrystals from pistachio shells via acid hydrolysis. [J]. Journal of Industrial Crops & Products, 2017, 109: 869– 874.

CrossRef - Arzu Y, Seda E, Serap Optimum alkaline treatment parameters for the extraction of cellulose and production of cellulose nanocrystals from apple pomace: [J]. Journal of Carbohydrate Polymers, 2019, 215:330-337.

CrossRef - Abdulraheem, M.I., Hu, , Ahmed, S.; Li, L.; and Naqvi, SMZA (2023): Advances in the Use of Organic and Organomineral Fertilizer in Sustainable Agricultural Production. In Book: Organic Fertilizer. IntechOpen. 1 – 20. http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.1001465

CrossRef - Khan, , Raghunathan, V., Singaravelu, D. L., Sanjay, M. R., Siengchin, S., Jawaid, M., Asiri, A. M. (2020). Extraction and Characterization of Cellulose Fibers from the Stem of Momordica Charantia. Journal of Natural Fibers, 19(6), 2232–2242. https://doi.org/10.1080/15440478.2020.1807442

CrossRef - Ali S, Rani A, Dar MA, Qaisrani MM, Noman M, Yoganathan K, Asad M, Berhanu A, Barwant M, Zhu Recent Advances in Characterization and Valorization of Lignin and Its Value-Added Products: Challenges and Future Perspectives. Biomass. 2024; 4(3):947-977.

CrossRef - Zhang, , Zhang, H., Li, D., Abass Z.; Abdulraheem, M.I., Su, R., Ahmed, S. & Hu, J. (2021): Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy for the quantitative detection of abscisic acid in wheat leaves using silver coated gold nanocomposites. Spectroscopy Letters, DOI: 10.1080/00387010.2021.1995

- Martillanes, , Ayuso-Yuste, M.C., Bernalte, M.J. et al. Cellulase-assisted extraction of phenolic compounds from rice bran (Oryza sativa L.): process optimization and characterization. Food Measure 15, 1719–1726 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11694-020-00773-x

CrossRef - Driaa, E.K., Maarir, H., Mennani, M., Grimi, N., Moubarik, A. and Boussetta, N., 2025. Ultrasound, pulsed electric fields, and high-voltage electrical discharges assisted extraction of cellulose and lignin from walnut shells. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 292, p.139319.

- Kandhola, , Djioleu, A., Rajan, K. et al. Maximizing production of cellulose nanocrystals and nanofibers from pre-extracted loblolly pine kraft pulp: a response surface approach. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 7, 19 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40643-020-00302-0

CrossRef

- Kasiri N, Fathi (2018) Production of cellulose nanocrystals from pistachio shells and their application for stabilizing Pickering emulsions. Int J Biol Macromol. 106:1023-1031. doi: 10.1016/ j.ijbiomac.2017. 08.112.

CrossRef - Mkilima, , et al., Investigating the potential of wheat straw and pistachio shell as a bio- functionalized agricultural waste biomass for enhanced biosorption of pollutants from wastewater. Case Studies in Chemical and Environmental Engineering, 2024. 9: p.100662.

CrossRef - Gabriel, , Belete, A.., Syrowatka, F., Neubert, R. H. H., Gebre-Mariam, T. (2020). Extraction and characterization of celluloses from various plant byproducts. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 158: p. 1248-125

CrossRef

Abbreviations

NaOH: Sodium hydroxide

H2O2: Hydrogen peroxide

RSM: Response surface methodology

R2: Coefficient of determination (statistical term)

p: p-value (statistical term)

rpm: revolutions per minute

SCUT: South China University of Technology

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.