Manuscript accepted on : 14 Apr 2025

Published online on: 17-04-2025

Plagiarism Check: Yes

Reviewed by: Dr. Sayed Hussain

Second Review by: Dr. M M V Baig

Final Approval by: Dr. Eugene A. Silow

Monika Chaudhary1 , Amar Prakash Garg 2*

, Amar Prakash Garg 2* and Dilfuza Jabborova3

and Dilfuza Jabborova3

1School of Biotechnology and Life Sciences, Shobhit Institute of Engineering and Technology, Meerut, India.

2Research and Development Cell, Swami Vivekanand Subharti University, Subhartipuram, Meerut, India

3 Department of Plant Microbe Interaction, Institute of Genetics and Plant Experimental Biology, Kibray, Uzbekistan

Corresponding Author E-mail: amarprakashgarg@yahoo.com

DOI : http://dx.doi.org/10.13005/bbra/3387

ABSTRACT: Serendipita indica is a root endophytic fungus that promotes overall plant development by forming a symbiotic relationship with the roots of vascular host plants. Azotobacter is a Gram-negative, motile, aerobic, free-living bacteria, used as a biofertilizer, improves seed germination, overall plant development and yield of various crops. In this paper, we are evaluating the impact of combinatorial effect of Serendipita indica and Azotobacter chroococcum on root colonization and soil enzyme activity of Oryza sativa. The study utilized cultures of S. indica and A.chroococcum grown in jaggery- based broth for bulk multiplication. Tests in the field were carried out during May–October 2023, with treatments: Control (C), T1 (A. chroococcum), T2 (S. indica), and T3 (combination) with 3 replicates and approximately 100 plants each replicate. Root colonization was examined using Trypan blue staining, and soil enzyme activities (alkaline phosphatase, urease, and dehydrogenase) were measured following standard protocols. This study evaluated the effects of Serendipita indica and Azotobacter chroococcum on soil enzymes in two rice types i.e. PB1121 and PB1718. PB1718 exhibited higher soil dehydrogenase activity, while PB1121 showed greater increases in alkaline phosphatase and urease activities. In PB 1121, the combined treatment of S. indica and A. chroococcum significantly boosted soil dehydrogenase (148.2%), urease (89.5%), and alkaline phosphatase (109.9%) activities, demonstrating strong synergy. Similarly, in PB 1718, these activities increased 219.8, 70.5 and 27.2%, respectively, with a greater rise in urease and phosphatase in PB 1121, while PB 1718 exhibited a higher enhancement in dehydrogenase activity.. The in-depth analysis provides valuable insights into synergistic effect of S. indica and A. chroococcum on plant root system and soil enzyme activity.

KEYWORDS: A. chroococcum; Endophyte; Root colonization; Soil activity; S.indica

Download this article as:| Copy the following to cite this article: Chaudhary M, Garg A. P, Jabborova D. Root Colonization of Rice by Serendipita indica and Azotobacter chroococcum and their Soil Enzyme Activity. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(2). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Chaudhary M, Garg A. P, Jabborova D. Root Colonization of Rice by Serendipita indica and Azotobacter chroococcum and their Soil Enzyme Activity. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(2). Available from: https://bit.ly/44t3rqN |

Introduction

In natural ecosystems, plants engage in complex interactions with a diverse array of microorganisms, which can significantly influence their growth, development, and overall fitness. These interactions can range from beneficial to detrimental, depending on the nature of the relationship. Among the most studied and ecologically significant interactions are those involving mutualistic symbiosis, where both the plant and the microorganism derive substantial benefits. Many microorganisms interact with plants in nature, influencing their growth and development in both positive and negative ways. In mutualistic symbiosis, both the plant and the microorganism benefit from the relationship. For example, Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi (AMF), a type of symbiotic fungus, can form beneficial partnerships with about 80% of all known land plants. These fungi help plants grow better, absorb water more efficiently, use nutrients effectively, and tolerate environmental stress. In return, the plant provides the fungi with carbon in the form of sugars. Serendipita indica, also known as Piriformaspora indica, is a well-known endophytic fungus that grows in plant roots. It was discovered in the root zones of drought-resistant plants, Prosopis juliflora and Zizyphus nummularia, in India’s Thar Desert by Professor Ajit Varma. 1-5

The endophytic fungus, S. indica forms symbiotic relationships with a variety plant species by colonizing their roots. The process begins with the germination of chlamydospores, primarily in the root zone, followed by the growth of a hyphal network on and inside the roots. The hyphae branch out, penetrate the outer root layers, and continue growing to surround the rhizodermal and cortical cells. 6-7While the fungus avoids the conductive tissues of roots, it colonizes mature root sections both within and between cells. Different parts of the root are colonized, with the cell differentiation zone having the highest levels of fungal presence. The fungus also enters root hair cells, where its hyphae grow from the germinated spores. This extensive colonization of the root system allows S. indica to exert its plant growth-promoting effects, which include enhanced nutrient uptake, improved stress tolerance, and increased resistance to pathogens. 8-10 The symbiotic relationships between plants and fungi Serendipita indica, play a crucial role in enhancing plant growth and stress tolerance. S. indica colonizes the roots of a wide range of plant species, promoting growth and stress tolerance through various mechanisms. Both fungi provide significant benefits to their host plants, making them valuable tools for sustainable agriculture and ecosystem management.

Azotobacter are round or oval-shaped, motile bacteria belonging to the Azotobacteraceae family in the kingdom Bacteria. They are known for their thick-walled cysts and their ability to produce large amounts of extracellular slime. These free-living soil bacteria play a key role in nutrient cycling by mineralizing nutrients and fixing atmospheric nitrogen (N), releasing it into the soil as ammonium ions. Azotobacter has been studied as a model organism for nitrogen-fixing bacteria (diazotrophs) and is used to produce food additives, biofertilizers, and certain biopolymers. Being gram-negative, they grow best in neutral to alkaline soils.11 When used alone or combined with other bacterial biomass, has shown positive effects on the growth of many crops when applied as a biofertilizer. Kurrey, 12 found that onion plants inoculated with A. chroococcum had much higher levels of carotenoids and chlorophyll a and b compared to untreated plants. It is widely accepted as a natural alternative to chemical fertilizers because of its ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen. The application of Azotobacter significantly improved soil fertility and nutrient availability. Treated soils showed higher levels of organic carbon, available nitrogen, and other essential nutrients compared to untreated soils. The increase in nitrogen content was particularly notable, as Azotobacter is known for its nitrogen-fixing capabilities, which enhance soil nitrogen levels and reduce the need for chemical fertilizers. Additionally, the treated soils exhibited improved microbial activity, indicating a healthier soil ecosystem.

S. indica and A. chroococcum both microorganisms are known for their beneficial interactions with plants, enhancing nutrient uptake and providing resistance against various stresses. A study examined the deployment of a microbial consortium, including S. indica, Rhizophagus intraradices, and A. chroococcum, to boost drought tolerance in maize.13 Although direct studies on their combined effect on soil enzyme activities are not available, the individual positive impacts of each microorganism suggest that their joint application could lead to synergistic improvement in soil dehydrogenase, urease, and alkaline phosphatase activities. In this study, we aim to evaluate the impact of combinatorial effect of Serendipita indica and Azotobacter chroococcum on root colonization and soil enzyme activity on two varieties of Oryza sativa.

Materials and Methods

S. indica and A. chroococcum Culture

Dr. Ajit Varma of AIMT, Amity University, Noida graciously provided a culture of Serendipita indica which is normally cultured on Potato Dextrose, Hill and Kaefer, and yeast extract peptone glycerol (YPG) media. We have used a simple culture medium, developed by Attri et al.,14 containing fresh Jaggery (concentrated raw sugarcane juice) as an energy nutrition source. A medium containing 4% (w/v) Jaggery only was prepared, pH of 6.5 was adjusted and autoclaved at 15 p.s.i for 15 min in 1 litre Erlenmeyer flask containing 100mL medium and and A. chroococcum were inoculated aseptically and separately and incubated at 28 and 37 ℃ temperature respectively for 2-4 days for A. chroococcum and 10-14 days for S. indica in shake flasks at 120 rpm for bulk multiplication. Jaggery has been used in our laboratory for the culture of lactic acid bacteria also (Garg et al., 2025)32

Field Experiment

Twenty four fields (each measuring 2 x 2 meter) were prepared using standard agronomical practices for cultivation of two varieties of rice in research farm of Shobhit Institute of Engineering and Technology Meerut. Sowing was done in May 2023 and transplantation in July 2023 when the seedlings were 40-day-old having 8-10 cm in size. The rice varieties PB 1121and PB 1718 were procured from Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel University of Agriculture and Technology, Meerut and these are long duration varieties. All recommended standard cultivation practices for both varieties were used.

A Completely Randomized Design (CRD) with 3 replicates for each treatment was used in this study. 14-day-old microbial biomass of S. indica and 4-day-old biomass of A. chroococcum cultured in 100mL medium were added in 500g sterile saw dust as carrier and spread in 2 x 2 meter field where transplantation was made. Control (C) field was treated similarly but without microbial inoculum. Treatment (T1) was treated with A. chroococcum alone, T2 with S. indica alone while T3 included combination of both A. chroococcum and S. indica in equal ratio by mixing half of each inoculum.

Root Colonization and Staining

For staining of roots of Orzya sativa, tryphan blue staining method was used as given by. 15 To perform trypan Blue staining of roots, we began by thoroughly washing the roots with water to remove any soil or debris, then cut the roots into 1 cm segments to ensure uniform staining. Next, boil the root segments in a 10% (w/v) KOH solution for 10 minutes. This step clears the root tissues and enhances stain penetration. After boiling, we washed the roots again with water to remove excess KOH. Finally, the roots were stained by immersing them in a trypan Blue stain. To prepare 1 litre of trypan Blue stain solution, combine 500 mL of glycerol, 475 mL of distilled water, and 25 mL of acetic acid in a container. Then, add 0.1 g of trypan Blue powder to the mixture. Stir well until the stain is completely dissolved and the solution is homogeneous.

Soil enzyme Activity

Alkaline Phosphatase Activity

The alkaline phosphatase enzyme activity was assayed using a standard method described by Tabatabai and Bremner (1972).16 A one gram soil sample was placed in screw-capped tubes (30 mL) and treated with 0.25 mL of toluene, 4 mL of Modified Universal Buffer (pH-11), and 1 mL of 0.025 M p-nitrophenyl phosphate solution. The mixture was vortexed for 1–2 minutes and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. After incubation, 1 mL of 0.5 M CaCl₂ and 4 mL of 0.5 M NaOH were added. Soil blanks were prepared in the same way, but without the addition of p-nitrophenyl phosphate. The solution was filtered using Whatman filter paper No. 42, and the optical density of the yellow solution was measured at 420 nm. The alkaline phosphatase activity was expressed as micrograms of p-nitrophenol released per gram of soil.

Modified universal buffer (MUB) (pH-11) preparation:

To prepare the solution, dissolve 12.1 g of THAM (Tris-hydroxymethyl aminomethane), 11.6 g of maleic acid, 14 g of citric acid, and 6.3 g of boric acid. Add 488 mL of 1 N NaOH to the mixture. Adjust the volume to 800 mL and set the pH to 11 using 0.1 N NaOH. Finally, make up the volume to 1000 mL with distilled water.

Urease Activity

The urease enzyme activity was measured using a method described by Tabatabai and Bremner (1969). 17 In triplicate, 1 g of soil was placed in culture tubes (125 × 15 mm), and 500 μL of 0.8 M urea solution was added to each tube. The tubes were sealed and incubated at 37°C for 2 hours. After incubation, 1 N KCl (prepared in 0.01 N HCl) was added to each tube, and the tubes were shaken on a shaker for 30 minutes. The resulting suspension was filtered using Whatman filter paper No. 42. From the filtrate, 1 mL was mixed with 5 mL each of Reagent A (50 g phenol and 25 g sodium nitroprusside per litre, diluted 1:4 with distilled water) and Reagent B (25 g NaOH and 2.1 g sodium hypochlorite per litre, diluted 1:4 with distilled water). After 30 minutes, a blue color developed, and its optical density was measured at 625 nm.

Soil Dehydrogenase Activity

Dehydrogenase activity was determined using a standard method described by Casida (1964). 18 A total of 20 g of air-dried soil was mixed with 0.2 g of CaCO₃. From this mixture, 6 g of soil was placed into each of three culture tubes (125 × 15 mm). To each tube, 1 mL of 3% (w/v) triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) solution and 2.5 mL of distilled water were added. The contents were mixed thoroughly and incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. After incubation, 10 mL of methanol was added to each tube, vortexed for one minute, and filtered through Whatman filter paper No. 42. This step was repeated with another 10 mL of methanol. The optical density (OD) of the filtrate was measured at 485 nm, and dehydrogenase activity was expressed as micrograms of triphenylformazan (TPF) produced per gram of soil.

Statistical analysis

ANOVA was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 20 to analyze the experimental data. This method was used to determine whether the treatments had a significant or insignificant impact on rice traits such as soil enzyme activity. Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT) was applied to identify differences among treatments, with the least significant difference set at a 5% significance level (α=0.05\alpha = 0.05).

Results

Root Colonization

Microscopic examination of untreated Oryza sativa roots showed typical parenchymatous cells in the cortex, with normal microbial colonization while the roots collected from treated plants clearly revealed high degree of colonization with Serendipita indica within 30 days (Fig 1).

Using trypan blue staining technique, the colonization was distinctly visualized, revealing both ectomycorrhizal (Fig 1b) and endomycorrhizal (Fig 1c, 1d) associations. The staining revealed bulb-shaped, minute fungal structures penetrating into the parenchymatous cells of the root cortex. These structures, likely vesicles or arbuscules, are typical of endomycorrhizal fungi, which forms symbiotic relationship by penetrating plant root cells, aiding nutrient exchange. In addition to these fungal associations, branched hyphae were observed within clear, defined pockets inside the root cells, signifying extensive fungal colonization. Bacterial colonization was also evident around the surface of the hyphal fragments, suggesting a close symbiotic relationship between the fungus and bacterium. This intimate interaction may enhance the overall efficiency of nutrient uptake and promote plant growth, as the bacteria potentially benefit from the hyphal networks while contributing to the microbial ecosystem surrounding the root.

Thus, the combined fungal and bacterial colonization of Oryza sativa roots following S. indica treatment illustrates a complex and cooperative microbial community, likely to enhance the plant’s ability to absorb nutrients, resist stress, and promote overall plant health.

|

Figure 1: Variety PB1718 – (a) Control- No Inoculation (b) Root colonization by A. chroococcum (c) Root Colonization By S. indica (d) Root Colonization By S. indica & A. chroococcum (Arrows show the colonization by fungal hypha).Click here to view Figure |

On comparison of root colonization of the two varieties namely PB 1121 and PB1718, it was found that variety PB 1121 revealed greater penetration and colonization of the roots of Orzya sativa by the fungus S. indica than variety PB1718.

|

Figure 2: (a) Control- No Inoculation (b) Root colonization by A. chroococcum (c) Root Colonization by S. indica (d) Root Colonization By S. indica & A. chroococcum (variety PB1121).Click here to view Figure |

Soil Enzyme Activity

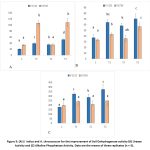

In the present study, it was revealed that the soil dehydrogenase activity in S. indica or A. chroococcum treated variety PB 1121 increased by 69.1 and 87% respectively over the control (Fig 5). The combined effect of S. indica and A. chroococcum further increased the soil dehydrogenase activity by 148.2% suggesting its synergistic action. Similarly, urease activity increased by 56.6 and 72.5% with S. indica and A. chroococcum, respectively, over the control. The combined application of both resulted in a synergistic increase of 89.5%.The alkaline phosphate activity after treatment with S. indica or A. chroococcum enhanced by 60 and 81.9% respectively over the control (Fig 3) and the combined treatment synergistically increased by 109.9%.

|

Figure 3: (A) S. indica and A. chroococcum for the improvement of Soil Dehydrogenase activity (B) Urease Activity and (C) Alkaline Phosphatase Activity. Data are the means of three replicates (n = 3).Click here to view Figure |

In variety PB 1718, soil dehydrogenase activity was enhanced by 1.8 and 214.8% under the influence of S. indica and A. chroococcum, respectively as compared to the control and the combination of both demonstrated a synergistic effect and reached to 219.8%. Similarly, urease activity increased by 6.6 and 29.5% with S. indica and A. chroococcum, respectively over the control and the combined application of both resulted in a significant increase in with 70.5%. Alkaline phosphatase activity also showed an improvement, with S. indica and A. chroococcum by 6.15 and 22.5%, respectively over the control. Their combined application further enhanced alkaline phosphatase activity by 27.2% (Fig. 3).

Discussion

The colonization of rice plant roots by Serendipita indica represents a significant symbiotic relationship that profoundly impacts plant growth and health. This beneficial fungus enhances the development of its host plants by establishing itself within the root system. 19 Upon colonization, S. indica forms a mycorrhiza-like association, characterized by the formation of intricate hyphal networks. These hyphae extend into the root cells, creating specialized structures known as arbuscules, which facilitate nutrient exchange between the fungus and the plant. The arbuscules, which branch out from the fungal mycelium into the root tissue, play a critical role in the mutualistic relationship by enabling the transfer of essential nutrients and promoting plant growth. Liu, 20 demonstrated the growth-promoting effects of S. indica by establishing a co-culture system with Oncidium plants in G10 media. The study revealed that the addition of S. indica plugs and chlamydospore suspensions to the rooting media of banana seedlings in vitro significantly accelerated plant development and reduced the time required for root formation. This highlights the fungus’s ability to enhance root growth and overall plant vigour. The role of S. indica in improving plant health and growth has been corroborated by other studies. For instance, Wu et al., 21 investigated the effects of S. indica inoculation on Camellia oleifera and observed a notable increase in root colonization rates, from 3.37% to 9.42%. This enhanced colonization was associated with improved plant height and a higher net photosynthetic rate, underscoring the fungus’s ability to boost plant physiological performance. The increased photosynthetic efficiency likely results from the improved nutrient uptake facilitated by the arbuscules, which act as hubs for nutrient exchange between the fungus and the plant.

They help the plant to absorb phosphorus and other important elements and in return take carbohydrates from the plant. The effective development of the symbiotic connection between S. indica and the host plant is highlighted by the presence of hyphal growth in the roots of rice plants dyed with trypan blue. 22 It is frequently feasible to see fungal structures in plant tissues and gauge the level of fungal colonisation by using trypan blue staining. The development of hyphae suggests that the rice plant’s roots are actively being colonised by fungi, indicating a functional mycorrhizal association that may offer the plant a number of advantages, including better nutrient uptake, increased resistance to environmental stress, and enhanced resistance to pathogens. S. indica’s colonisation of rice plant roots serves as further evidence of the significance of mycorrhizal symbioses in agricultural settings. 23 The size, height, number of roots, buds, and chlorophyll content of Aloe vera all increased significantly after treatment with S. indica. According to Atia, 24 S. indica significantly reduces the damage to the shoot and root biomass of infected cucumber plants. The findings demonstrated that P. indica inoculation significantly improved cucumber tolerance to root-knot nematodes. The fungus enhanced photosynthetic efficiency and chlorophyll content, indicating better plant health and growth despite nematode infestation. Soil dehydrogenase, urease, and alkaline phosphatase activities were also examined. A study conducted by Islam & Borthakur, 25 found that dehydrogenase activity was significantly correlated with nutrient content, particularly during the flowering stage of rice and also reported that alkaline phosphatase activity peaked during the flowering stage of rice, positively correlating with nutrient content .Similarly, Srinivas & Sridhar, 26 showed that the application of organic manure increased urease activity and significantly improved rice grain yield under flooded conditions. The study suggests that long-term application of organic manure, particularly when combined with inorganic fertilizers, improves soil urease activity and enhances rice grain yield under flooded conditions. This integrated approach promotes sustainable agriculture by maintaining soil health, improving nutrient availability, and increasing crop productivity, making it a viable strategy for rice cultivation in similar agro-ecosystems. In addition to improving plant growth and productivity, Azotobacter inoculation also modifies plant quality and reduces the need for artificial fertiliser. When Azotobacter was introduced to vegetable, cereal, and estate crops, the yield increased by 5–24% compared to when chemical fertilisers were used. 27 The application of S. indica and A. chroococcum, individually or in combination, has been shown to enhance soil enzyme activities, which are critical for soil health and fertility. Inoculating A. chroococcum has been reported to significantly increase dehydrogenase activity, reflecting enhanced microbial respiration and metabolic functions. 28 A. chroococcum, with its nitrogen-fixing capabilities, boosts urease activity, improving nitrogen availability, while S. indica positively influences urease activity, contributing to better nitrogen utilization.29 Additionally, S. indica has been reported to improve alkaline phosphatase activity, enhancing phosphorus uptake in crops like rice and rapeseed, while Azotobacter is reported to promote overall soil health, potentially influencing phosphorus mineralization. 30 As reported by Fu et al., 31 Oryza sativa (rice) showed that co-inoculation with S. indica and A. chroococcum increased nutrient acquisition, resulting in higher crop yields. The findings demonstrated that S. indica significantly improved the growth of Camellia oleifera by enhancing root and shoot biomass. The fungus also increased the uptake of essential nutrients, such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, which are critical for plant development. Additionally, S. indica inoculation led to higher sugar accumulation in the plants, indicating improved photosynthetic efficiency and carbohydrate metabolism. These positive effects were attributed to the fungus’s ability to enhance nutrient availability, stimulate root development, and modulate plant physiological processes. The application of A. chroococcum and S. indica together consistently produced the maximum increases in enzyme activity for both types, suggesting that these microbial inoculants have synergistic effects.

Conclusion

This study highlights the synergistic interaction between S. indica and A. chroococcum, significantly enhancing root colonization and soil enzyme activities in rice varieties PB 1121 and PB 1718. Microscopic analysis confirmed extensive root colonization, with S. indica forming both ectomycorrhizal and endomycorrhizal associations, while bacterial colonization around hyphal fragments suggested a mutualistic relationship. The combined inoculation led to the highest dehydrogenase (148.2%, 219.8%), urease (89.5%, 70.5%), and alkaline phosphatase (109.9%, 27.2%) activities in PB 1121 and PB 1718, respectively, demonstrating their synergistic effect. This enhanced nutrient uptake, plant health, and crop productivity. The findings confirm that microbial inoculants improve soil biochemical processes and nutrient cycling, reducing dependence on chemical fertilizers. The study emphasizes the potential of S. indica and A. chroococcum as biofertilizers, providing a sustainable approach to improving soil quality and rice yield.

Acknowledgement:

The author would like to thank Shobhit Institute of Engineering and Technology for granting the Ph.D. research work.

Funding Sources

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

This statement does not apply to this article.

Ethics Statement

This research did not involve human participants, animal subjects, or any material that requires ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not involve human participants, and therefore, informed consent was not required.

Clinical Trial Registration

This research does not involve any clinical trials.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

Not Applicable

Author contributions

Monika: Conceptualization and conduction of experiments, data collection and analysis.

Amar Garg: Data interpretation, photography, identification, designing of experiments and supervision of entire work, writing of manuscript

Dilfuza Jabborova: Finalization of experimental design, finalization of writing of paper, supervision of enzymatic analysis.

References

- Verma Savita, Ajit Varma, Karl-Heinz Rexer, Annette Hassel, Gerhard Kost, Ashok Sarbhoy et al., Piriformospora indica, gen. et sp. nov., a new root-colonizing fungus: Mycologia90, no. 5 1998: 896-903.

CrossRef - Michal Johnson, R. Oelmüller. Mutualism or parasitism: life in an unstable continuum. What can we learn from the mutualistic interaction between Piriformospora indica and Arabidopsis thaliana? : Endocytobiosis Cell Res.: J. Int. Soc. Endocytobiol. 2009, 19, 81–111.

- Parniske. Arbuscular mycorrhiza: the mother of plant root endosymbiosis: Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008, 6 (10) 763–775.

CrossRef - Weiß, F. Waller, A. Zuccaro, M.A. Selosse. Sebacinales–one thousand and one interactions with land plants: New Phytol. 2016, 211 (1) 20–40.

CrossRef - Bahadur A, Batool F, Nasir S, Jiang Q, Mingsen Q, Zhang J, Pan Y, Liu H, Feng Mechanistic insights into arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi-mediated drought stress tolerance in plants: J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20 (17) 4199.

CrossRef - Ntana F, Bhat WW, Johnson SR, Jørgensen HJ, Collinge DB, Jensen B, Hamberger BA. sesquiterpene synthase from the endophytic fungus Serendipita indica catalyzes formation of viridiflorol: Biomol. 2021, 11, 898

CrossRef - Qiang X, Weiss M, Kogel KH, Schafer P. Piriformospora indica—A mutualistic basidiomycete with an exceptionally large plant host range: Plant. Pathol, 2011, 13, 508–518.

CrossRef - Bleša, D; Orchideoid Mycorrhizal Fungi as Endophytes: Diploma Thesis, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic. 2018.

- Gill SS, Gill R, Trivedi DK, Anjum NA, Sharma KK, Ansari MW et al., Piriformospora indica: Potential and significance in plant stress tolerance: Microbiol, 2016, 67, 332.

CrossRef - Mensah RA, Li D, Liu F, Tian N, Sun X, Hao X et al., Versatile Piriformospora indica and its potential applications in horticultural crops: Plant J., 2020, 6, 111–121.

CrossRef - Dar SA, Bhat RA, Dervash MA, Dar ZA & Dar GH. Azotobacter as biofertilizer for sustainable soil and plant health under saline environmental conditions: Microbiota and Biofertilizers: A Sustainable Continuum for Plant and Soil Health, 2021, 231-254.

CrossRef - Kurrey DK, Sharma R, Lahre MK, & Kurrey RL. Effect of Azotobacter on physio-chemical characteristics of soil in onion field: Pharma Innov. J., 2018, 7(2), 108–113.

- Tyagi J, Mishra A, Kumari S, Singh S, Agarwal H, Pudake RN et al., Deploying a microbial consortium of Serendipita indica, Rhizophagus intraradices, and Azotobacter chroococcum to boost drought tolerance in maize: EEB. 2022.

CrossRef - Attri MK & Varma A. Comparative study of growth of Piriformospora indica by using different sources of jaggery: J Pure Appl Microbiol.2018 12, 933-942.

CrossRef - Phillips JM, Hayman DS. Improved procedures for clearing roots and staining parasitic and vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi for rapid assessment of infection: Trans Br mycol Soc.1970; 55:158–161.

CrossRef - Tabatabai MA and JM Bremner. Assay of urease activity in soils: Soil Biol. Biochem. 1972, 4:479-487.

CrossRef - Tabatabai MA, Bremner JM. Use of p-nitrophenol phosphate for the assay of soil phosphatase activity: Soil Biol. Biochem. 1969, 1, 301–307.

CrossRef - Casida LE, Klein DA, Santoro T. Soil dehydrogenase activity: Soil Sci. 1964, 98, 371–376.

CrossRef - Shukla J, Narayan S, Mishra A, Shirke PA, Kumar M. Reduction of arsenic accumulation in rice grain by endophytic fungus Serendipita indica: Rhizosphere, 2023, 26, 100680

CrossRef - Liu HC, Li MJ, Jin L, Tian DQ, Zhu KY, Zhang JQ, Tang C . Effects of Piriformospora indica on growth of oncidium seedling in vitro: ZAAS, 2019, 60(4):642-645.

- Wu C, Yang Y, Wang Y, Zhang W & Sun H. Colonization of root endophytic fungus Serendipita indica improves drought tolerance of Pinus taeda seedlings by regulating metabolome and proteome: Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1294833.

CrossRef - Cao MA, Liu RC, Xiao ZY, Hashem A, Abduallah EF, Alsayed MF et al., Symbiotic fungi alter the acquisition of phosphorus in Camellia oleiferathrough regulating root architecture, plant phosphate transporter gene expressions and soil phosphatase activities: Fungi, 2022, 8, 800.

CrossRef - Bhatnagar VS, Bandyopadhyay P, Rajacharya GH, Sarkar S, Poluri KM, Kumar S. Amelioration of biomass and lipid in marine alga by an endophytic fungus Piriformospora indica: Biofuels. 2019, 12(1):12-176.

CrossRef - Atia MAM, Abdeldaym EA, Abdelsattar M, Ibrahim DSS, Saleh I, Elwahab MA, Osman GH et al., Piriformospora indica promotes cucumber tolerance against root-knot nematode by modulating photosynthesis and innate responsive genes: Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019 27(1):279-287.

CrossRef - Islam NF & Borthakur B. Effect of different growth stages on rice crop on soil microbial and enzyme activities: Plant Res., 2016, 3(1), 40-47.

- Srinivas D & Sridhar TV. Urease Activity and Grain Yield of Rice as Influenced by the Long-term Effect of Application of Organic Manure and Inorganic Fertilizers under Flooded Conditions: The Andhra Agric. J, 2022, 69(2), 199-203.

- Hindersah R, Kamaluddin NN, Samanta S, Banerjee S, and Sarkar, S. Role and perspective of Azotobacter in crops production: STJSSA, 2020, 17(2): 170-179

CrossRef - Kumar S & Sindhu SS. Drought stress mitigation through bioengineering of microbes and crop varieties for sustainable agriculture and food security: res. Microbial., 2024, 7, 100285.

CrossRef - Xiong Q, Hu J, Wei H, Zhang H & Zhu J. Relationship between Plant Roots, Rhizosphere Microorganisms, and Nitrogen and Its Special Focus on Rice: Agriculture, 2021, 11(3), 234

CrossRef - Saleem S, Sekara A & Pokluda R. Serendipita indica-A Review from Agricultural Point of View: Plants, 2022, 11(24), 3417.

CrossRef - Fu Wan-Lin, Wei-Jia Wu, Zhi-Yan Xiao, Fang-Ling Wang, Jun-Yong Cheng, Ying-Ning Zou et al., Serendipita indica: A Promising Biostimulant for Improving Growth, Nutrient Uptake, and Sugar Accumulation in Camellia oleifera : Horticulturae.10, no. 9 (2024): 936.

CrossRef - Garg, Amar Prakash, Anchal Bamal and Rashmi Goley. A better and cheaper culture medium for isolation of lactic acid bacteria from milk and its products. Biosciences Biotechnology Research Asia. 2025, 22(1): 149-155.

CrossRef

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.