Manuscript accepted on : 23-05-2025

Published online on: 23-06-2025

Plagiarism Check: Yes

Reviewed by: Dr. Parasuraman S

Second Review by: Dr. Amit Panaskar

Final Approval by: Dr. Eugene A. Silow

Rohit Jaysing Bhor1* , Mayur Sitaram Gaikwad2

, Mayur Sitaram Gaikwad2 , Harshali Narayan Anap3

, Harshali Narayan Anap3 , Vaishanavi Parashuram Vikhe1

, Vaishanavi Parashuram Vikhe1 , Mayuri Rajendra Dighe1

, Mayuri Rajendra Dighe1 , Harsh Mahesh Kashid1

, Harsh Mahesh Kashid1 , Nikita Machhindra Jondhale1

, Nikita Machhindra Jondhale1 , Sakshi Uttam Mulay1

, Sakshi Uttam Mulay1 , Urmila Suryaji Gaikwad1

, Urmila Suryaji Gaikwad1 and Sunil Eknath Jadhav1

and Sunil Eknath Jadhav1

1Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, Savitribai Phule Pune University, Pravara Rural College of Pharmacy, Pravaranagar, Maharashtra, India.

2Matoshri Miratai Aher College of Pharmacy, Karjule Harya, Maharashtra, India

3Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, MABD Institute of Pharmaceutical education and Research, Yeola, Maharashtra, India

Corresponding Author E-mail:rohit.bhor69@gmail.com

DOI : http://dx.doi.org/10.13005/bbra/3388

ABSTRACT: The proposed approach summarizes each activity in silico research. The structure-activity correlations and pharmacological effects of compounds containing Triazole are examined in this study. Using a variety of computational techniques, in silico studies allow for forecasting structural changes and how they would impact the pharmacological properties as well as the efficiency of these modifications. The aim of this study was to investigate 3LAM (PDB 00003lam)enzyme inhibitory, and HIV-1 reverse transcriptase activities of a new series of 1H-Triazole derivatives, for their possible use as multi-action therapeutic agents. Molecular Design Suite was used to conduct Combi Lab investigations and 3D-QSAR. Pyrexand Biovia software was used for the molecular docking investigation. The results show that Doravirine (− 9.1 kcal/mol) and its analogue (− 8.3 kcal/mol) showed better binding affinity with 3LAM (PDB 00003lam)with amino acids LYS154: LYS385; GLY384:UNK1; LYS385; ILE94; TRP88; TRP88:O; B:TRP383TRP383;MET184; LYS385; UNK1; THR386; THR386; GLN182 ILE94; GLY384:O - TRP383. The top 10 predicted drugs containing The computational study of Triazole derivatives is the main topic of this article. All compounds' cytotoxicity against HIV-1 reverse transcriptase was assessed, and the outcomes showed that several of them had strong inhibitions. This study determined the structural elements affecting by carefully changing the substituents, ring modifications, and linker groups. The logical creation and optimization of more powerful and selective molecules is made possible by these discoveries. The current findings are limited to in silico analysis and lack in vivo efficacy. Millions of people are living with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), which causes AIDS or AIDS- related complex. HIV-1 reverse transcriptase (RT) is one of the key viral targets for HIV-1 inhibition. In the present work, new Doravirine 1H-Triazole derivatives heterocyclic Schiff base complexes as HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibitors have been synthesized. Molecular orbital energy calculations of the synthesized 1H-Triazole complexes have been studied, in which the complexes were theoretically optimized. Geometrical structures of the complexes were found to be square pyramidal and square planar. To test the reverse transcriptase inhibition activity of the ligands and their 1H-Triazole complexes, HIV-1 RT kit assay was used. Doravirine was used as reference drug. 1H-Triazole complexes were found to exhibit higher anti-HIV activity than pyrrole copper complexes.

KEYWORDS: ADMET; HIV-1 resistance; 3LAM (PDB 00003lam); Molecular docking; Triazole

Download this article as:| Copy the following to cite this article: Bhor R. J, Gaikwad M. S, Anap H. N, Vikhe V. P, Dighe M. R, Kashid H. M, Jondhale N. M, Mulay S. U, Gaikwad U. S, Jadhav S. E. Molecular Docking Insights into Doravirine Derivativeson3LAM (PDB 00003lam) RT Inhibitors: A Target Protein Involved in HIV-1 infections. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(2). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Bhor R. J, Gaikwad M. S, Anap H. N, Vikhe V. P, Dighe M. R, Kashid H. M, Jondhale N. M, Mulay S. U, Gaikwad U. S, Jadhav S. E. Molecular Docking Insights into Doravirine Derivativeson3LAM (PDB 00003lam) RT Inhibitors: A Target Protein Involved in HIV-1 infections. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(2). Available from: https://bit.ly/3ZKIFzX |

Introduction

The emergence of HIV-1 resistance linked to RT amino acid alterations necessitates the creation of innovative theories that clarify the connections between a specific HIV-1 RT conformation and treatment resistance. These data can be used to predict HIV-1 resistance to antiretroviral medications and/or to further develop novel HIV-1 RT inhibitor.1 New drugs that are effective against the mutant versions of HIV-1 RT may potentially be discovered using this technique. Docking-based methods can be used to forecast the significance of mutations for HIV-1 resistance if the molecular docking process is carried out utilising a data set of known medications. Unlike SAR analysis, which necessitates information on a set of low molecular weight compounds and their effects on a specific protein, molecular docking can be performed if data are available on at least one protein-ligand (protein-low molecular weight compound) complex. The molecular docking methods are reviewed often. RT inhibitors come in two primary varieties; they interact with RT at its active site.2 Didanosine, lamivudine, abacavir, stavudine, and tenofovir disoproxil are among the NRTIs that have received clinical approval. Doravirine is a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor drug that was created by Merck & Co. to treat HIV and is marketed under the trade name Pifeltro.The exploration and subsequent synthesis of innovative hybrid molecules, characterized by a multifaceted array of pharmacological activities achievable through the modulation of a diverse spectrum of biochemical pathways, holds considerable promise in the therapeutic intervention of a wide range of pathological conditions, as it is well acknowledged that multifactorial disorders can have multiple origins.3 Because the hazards of drug-drug interactions are reduced, this approach has distinct advantages over drug combinations or multicomponent medications, notwithstanding the enormous difficulty in designing and optimizing such molecules. The synchronized combining of various advantageous moieties on similar substance, particularly for treatment of particular illness, is one of the promising developments in drug discovery.4 The exordium for engendering avant-garde compounds exhibiting pleiotropic pharmacological effects resides optimally within the domain of pharmaceutical advantages that mitigate the exigency for polypharmacy, encompassing therapeutic modalities that concurrently attenuate iatrogenic sequelae, abrogate symptomatic manifestations, or potentiate salutary outcomes via adjuvant therapeutic mechanisms.5 Even if they have a lot of potential for therapeutic use, this is important to assess possibility of adverse consequences. High atomic weight is a common characteristic of dual inhibitors, which may lessen the likelihood of their therapeutic effects. Consequently, while designing dual inhibitors, the safety profiles and pharmacokinetic characteristics must be carefully taken into account.6 Because of their many effects of this heterocyclic nucleus, i.e., analgesic, anti-tumor, antiviral, and psychoactive properties, they have played a significant role in medicinal chemistry. The intricate biological reaction with viral infections, which is defensive action towards immune cells.7 In human viral infection, 3LAM (PDB 00003lam) contributes to angiogenesis as well as cell division and death. One technique for figuring out how a protein and ligand interact is called molecular docking, and it explains the molecule’s orientation, binding interactions, and binding energy.8-9 Predicting the shared molecular characteristics those in molecular interactions with biological target and initiate response requires the use of pharmacophore methods.10 The purpose of this investigation was to determine the molecular interactions in Triazoles analogues as well as to screen the synthetic compounds’ physicochemical and ADMET characteristics.11 Additionally, pharmacophore modelling studies were used to examine distinctive traits. Since Triazole derivatives reported to have anti-viral features, it is necessary to demonstrate how they work.12 As a result, in-silico research helps identify how Triazoles work to block 3LAM (PDB 00003lam) enzymes, which is what gives them their Anti-viral infection properties. HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase enzyme is a vital defensive mechanism against all forms of physical, chemical, and viral assault.13 When this mechanism is dysregulated, the body develops pathological conditions, such as organ rejection, autoimmune diseases, and allergies.14 Needleman and Isakson originally described two cyclooxygenase isoenzymes in 1997. The “Inducible” enzyme, 3LAM (PDB 00003lam), causes viral reactions and is triggered by a variety of events. It is currently unclear what the exact roles of a 3LAM (PDB 00003lam) isoform that is solely expressed in particular brain and spinal cord areas. Numerous studies have linked 3LAM (PDB 00003lam) to a range of viral illnesses gives result, also used in viral infection treatment.15 In order to mitigate these serious side effects, selective 3LAM (PDB 00003lam), inhibitor medications were created. These medications have viral inhibitor property same as non-selective inhibitors, but they also have improved gastric safety profiles. The distinct chemical makeup of 3LAM (PDB 00003lam) was associated with their adverse effects. As a result, research for selective anti-viral medications with superior safety profiles than the others anti-viral drugs on the market is still ongoing.163LAM (PDB 00003lam), activity of inhibition synthesized derivatives were evaluated. Lastly, the synthesized compounds docked into 3LAM (PDB 00003lam), site to clarify their possible method of action.17

Material and Method

Molecular Docking and Ligand preparation

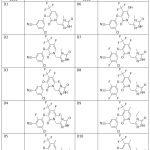

Preceding molecular docking, test compounds of Derivative’s 1–Derivative’s 10 structures and scheme of Triazole were given in Table 1. We optimized by using the semi-empirical approach and the ArgusLab 4.0.1 software program. Getting proteins ready We used a variety of different 3LAM (PDB 00003lam), enzyme crystal structures via the RCSB for docking studies. Maestro 11.9 was used for all computational analysis.18-20 Software were installed on Dell Inc. 27-inch computer that was on Linux x86_64 as OS and has Intel Core i7-7600U CPU at 3.90 GHz x8 with 16 GB RAM and 1 TB SSD. Drug likeness, physicochemical characteristics, and ADMET of compounds were studied. The PDB supplied Ribbon composition for 3LAM (PDB 00003lam).21 Auto dock version was 1.5.6. Chain A was chosen. Hydrogen with polarity and Gasteiger charges introduced after water was removed. The compounds’ 2D formula was drawn using ChemDraw Ultra 12.0. Avogadro software was used to minimize energy use. Autodock Vina was used to realize the docking process, while Discovery Studio 3.5 was used to visualize the interactions. 3LAM (PDB 00003lam) crystal structures were compared to the anticipated conformations of docking data of derivatives in order to optimize the docking method. Table 1 showed the superimposition of structure.

|

Table 1: Derivativesofdesignedcompound of Triazole DerivativesClick here to view Table |

Results

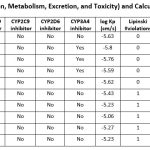

Molecular modelling utilizes quantum techniques to evaluate possibility of interaction, including cytochrome P450s, which has role in ADME processes.22-25 QSAR techniques is commonly used for data modellingof Derivative’s 1–Derivative’s 10. These look for relationships between a collection of chemical and structural molecules likes GI absorption; BBB permeant; Pgp substrate; CYP1A2 inhibitor; CYP2C19 inhibitor; CYP2C9 inhibitor; CYP2D6 inhibitor; and CYP3A4 inhibitor in question and certain property using statistical methods.26-28 Choosing appropriate mathematical method, appropriate chemical descriptors for ADMET endpoint, sizable enough collection of data pertaining with same endpoint for model validation are all essential components of effective prediction models for ADMET parameters. Good ADMET property prediction techniques are becoming more and more necessary to achieve two main goals.29-31 In order to lower the risk, novel compounds libraries should be designed first. Secondly, screening and testing should be optimized by focusing on the most promising compounds. Predicting characteristics like oral absorption, bioavailability, BBB penetration, clearance, and Vd (for frequency) which give information about dosage quantity and frequency is our goal. Molecular modelling and data modelling are the two categories of computational techniques that are employed.32-33 Recent developments in the prediction of ADME-related physicochemical qualities (like lipophilicity), ADME properties (like absorption), and toxicity problems (like drug–drug interactions) are discussed in this article see Table number 2. During the next ten years or so, automated medium and HTS in-vitro tests will be employed.Another potential future avenue for molecular docking techniques is the creation of methods that might enhance the prediction of RT inhibition. We believe that developing new techniques that allow for the consideration of small molecule pharmacophores in addition to docking data may be beneficial. There is also a great need for new methods that machine learning techniques to improve docking scoring functions might result in a notable improvement in the prediction value of molecular docking. Specifically, there are several studies that used different machine learning techniques to estimate the binding affinities of different sets of ligands. Given the information on mutations and resistance linked to them, we suggest that it may be extensively utilized in HIV-1 resistance research. Together with docking findings, information about the correlations between the prevalence of a certain mutation and decreased drug sensitivity may be utilized as descriptors in machine learning. We propose that the ability to incorporate information on the 3-dimensional complex inhibitor into the model can result in notable enhancements in the prediction of pharmacological activity.QSAR is one such technique that was covered drug discovery in the above session/chapter. In this above session/chapter will cover the newly developed idea of “drug-likeness” as well as the computer modelling of a number of biological and physicochemical characteristics that are crucial in turning a clinical lead into a commercially available medication. Pharmacologists and medicinal chemists have looked for beneficial drug-like chemical characteristics that produce agents with predictable oral therapeutic effectiveness. Drug development process follows Lipinski’s “rule of five” which is computational and experimental method for estimating solubility, permeability. 3LAM (PDB 00003lam)enzymes were docked with the drugs, and the molecular interactions between them were examined. Tables number 4 summarize interactions between chemicals with residues of dynamic amino acids, whereas Table number 3 display the 2D – 3D conformations for molecular bindingsof Derivative’s 1–Derivative’s 10. Computer-aided molecular design (CAMD) has traditionally concentrated on lead optimization and identification, and several creative techniques have been created to help increase the binding affinities of drug candidates to certain receptors. Those are general guideline which assesses drug-likeness and establishes whether molecule has pharmacological activity. The rule was founded on the finding that the majority of medications that work well when taken orally are tiny, somewhat lipophilic molecules. It is employed in the process of developing new drugs when pharmacologically active lead structures are gradually improved to boost their activity and selectivity while maintaining their drug-like physicochemical characteristics. Bonds rotation; H-bond acceptors; H-bond donors; Lipinski; Ghose; Veber; Egan and Muegge violations were given in Table number 2. ADMET (which stands for absorption, distribution, excretion, and toxicity) characteristics for substances are necessary to create effective oral medications. The toxicity of a ligand is thought to be required to ligand as function to effective discovery tool, and Qik-Prop produces physically relevant descriptions. The Ligprep module used for ligand preparation utilized in investigation. The protein preparation wizard utilized for protein preparation. The PDB data bank provided the X-ray crystal structures of 3LAM (PDB 00003lam), based on the optimal ligand-protein interaction, the scoring function assigns points. The extra-precision mode was used to assess the docking positions. The program detects steric conflicts, metal-ligation interactions, hydrophobic interactions, and hydrogen bonding. Every substance has a molecular weight between 400 and 500, which is less than 500. The compounds’ computed log P values fall between 3.56-5.35. The substances being studied have donors of hydrogen bonds.

|

Table 2: In silico ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) and Calculations of Lipinski’s rule of Five and Druglikeness |

|

Table 3: Docking Poses 2D and 3D |

Discussion

Three-dimensional (3D) and two-dimensional (2D) structures of RT with mutation-induced amino acid alterations are necessary for molecular docking. Several biochemical approaches can be used to gather information. Analogues with best interactions and far from zero auto dock score determined as best conformation. All of the “compounds had molecular weights less than 500,” according to data warrior results, suggesting that they will bind action site. To have a good in vivo response, pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetic characteristics must be balanced. Further details on medication dose and regimen are also provided by ADMET. According to “Lipinski’s rule of five”, an oral medication is selected if its molecular weight is < 500, hydrogen bond donors is less than 5, hydrogen bond acceptors is less than ten, and log P value less than five. Oral bioavailability depends on molecular flexibility, which is shown by the number of rotatable bonds. Additionally, as TPSA is indirectly related to percentage absorption, it suggested that used as 3D descriptor in number of hydrogen bonding groups. All drugs had LogP below 5, which indicates excellent penetration and absorption across cell membranes. Table 1 provides various derivatives of Triazole which specifics on the “binding energies and hydrogen bonds” of Derivative’s 1–Derivative’s 10. Furthermore, the dock score values of all the produced compounds ranged from 9.5 and 8.5 kcal/mol, suggesting their binding energies lower to Triazole, which has “binding energy” of 9.5 kcal/mol. Interactions towards 3LAM (PDB 00003lam) revealed that they have anti-viralproperties. N:UNK1:H – B:THR377:OG1;N:UNK1:C – B:GLN373:OE1;B:VAL108:O – N:UNK1:F;B:ASP186:OD1 – N:UNK1:F;B:ASP186:OD1 – N:UNK1:F;B:ASP186:OD2 – N:UNK1:F;B:GLN373:CB – N:UNK1;B:TYR232 – N:UNK1;B:TYR232 – N:UNK1;N:UNK1 – B:TYR232;B:TYR232 – N:UNK1:Clwere active amino acids 3LAM (PDB 00003lam). Derivative’s5 and Derivative’s 6 demonstrated Pi-Pi stacking to B:HIS96:HN – N:UNK1:F;N:UNK1 – B:ILE94;B:HIS96:HN – N:UNK1:O;B:TYR181:HH – N:UNK1:N;B:MET184:HN – N:UNK1:O;N:UNK1:H – B:GLN182:O;B:GLY93:CA – N:UNK1:F;B:PRO95:CA – N:UNK1:F;N:UNK1:C – B:GLY384:O;B:TRP88:O – N:UNK1:F;B:TRP88:O – N:UNK1:F;B:GLU89:O – N:UNK1:F;B:GLU89:O – N:UNK1:FB:ILE94:O – N:UNK1:F;N:UNK1:F;B:PRO321;N:UNK1:Cl via the Triazole and H-bond with Ser-530 via nitrogen of the Triazole ring. Derivative’s 10 demonstrated Pi-Pi stacking with Tyr385 via the Triazole ring and hydrogen bonding with Ser530. Derivative’s 10 demonstrated Pi-Pi stacking with A:GLN507:NE2 – N:UNK1:O;N:UNK1:HA:TYR532:OH;A:TRP406:CD1:UNK1:N;A:GLU404:OE2 – N:UNK1:F;A:TRP535:N – N:UNK1;A:ALA534:CA – N:UNK1;N:UNK1:Cl – A:LYS431;N:UNK1:C – B:GLY384:O;B:TRP88:O – N:UNK1:F; B:TRP88:O – N:UNK1:F;B:ASP186:OD2 – N:UNK1:Fvia benzene ring and H-bond with Met-522 via nitrogen. Comparing the 10Triazole derivatives to the standard drug, Derivative’s 10 and Derivative’s9 had a satisfactory docking score of -8.572 kcal/mol. B:GLN373:CB – N:UNK1;B:TYR232 – N:UNK1;B:TYR232 – N:UNK1; B:HIS96:HN – N:UNK1:O;B:TYR181:HH – N:UNK1:N;B:MET184:HN – N:UNK1:O; N:UNK1:H – B:GLN182:O, were active amino acids in the enzyme 3LAM (PDB 00003lam)enzymes. Comparing 10Triazole derivatives to the standard drug(-10.099 kcal/mol),Derivative’s 5, Derivative’s 6, Derivative’s 5, Derivative’s 9 and Derivative’s 10 showed elevated docking scores, from -9.25 to -9.51 kcal/mol (Table 4). Compound Derivative’s 5’s binding affinity score with 3LAM (PDB 00003lam)is -56.79 kcal/mol, whereas compound Derivative’s 6 binding score with 3LAM (PDB 00003lam) is -60.27 kcal/mol. Late-stage drug attrition may now be decreased and the most promising compounds can be found using in silico ADME screens. They should thus have high oral absorption; nevertheless, this quality cannot be used to explain variances in bioactivity. Additionally, the compounds’ oral absorption percentage ranged from 70.69 to 73.87%, indicating high ADME. Their TPSA values were 101.3 and 104.80 A2 (140 A2), respectively, and rotatable bonds ranged in 7 to 8 (<10). It is generally accepted that a molecule that is soluble in water and satisfies Lipinski’s and Veber’s criteria is said to possess both lipophilicity and hydrophilicity. Interactions towards 3LAM (PDB 00003lam) enzymes revealed that they have anti-viral properties. Comparing 10Triazole derivatives to the standard drugs (-10.099 kcal/mol), Late-stage drug attrition may now be decreased and the most promising compounds can be found using in silico ADME screens. To have a good in vivo response, pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic characteristics must be balanced. Further details on medication dose and regimen are also provided by ADMET.

Table 4: The active amino residues, bond length, bond category, bond type, ligand energies, and docking scores.

| Name | Distance | Category | Type | Docking Score |

| D7 | ||||

| B:LYS154:HZ1 – | 2.68372 | Hydrogen Bond;Halogen | H-Donor;Halogen Acceptor | -9.2 |

| B:LYS385N:UNK1 – | 3.05367 | Hydrogen Bond;Halogen | H-Donor;Halogen Acceptor | |

| B:GLY384:O – N:UNK1:F | 3.64144 | Hydrogen Bond;Halogen | H-Donor;Halogen Acceptor | |

| B:LYS385:NZ – N:UNK1 | 3.10072 | Halogen | H-Donor;Halogen Acceptor | |

| B:ILE94:CB – N:UNK1 | 3.20925 | Halogen | Pi-Orbitals | |

| B:TRP88 – N:UNK1N:UNK1:C – | 2.98246 | Halogen | Halogen Acceptor | |

| B:TRP88:O | 3.26362 | Halogen | Halogen Acceptor | |

| B:TRP383:O -N:UNK1:F | 3.47908 | Halogen | Halogen Acceptor | |

| B:TRP383:O – N:UNK1:F | 3.211195.32245 | Halogen | Halogen Acceptor | |

| B:MET184:HN – N:UNK1:O | 5.32245 | Halogen | Halogen Acceptor | |

| B:LYS385:HZ2 – N:UNK1:F | 2.98246 | Hydrophobic | Halogen (Fluorine) | |

| B:THR386:HN – N:UNK1:N | 3.17501 | Hydrogen Bond;Halogen | Halogen (Fluorine) | |

| B:THR386:HG1 – N:UNK1:N | 3.8068 | Hydrogen Bond;Halogen | Pi-Cation | |

| B:GLN182:O | 3.78708 | Halogen | Pi-Sigma | |

| B:ILE94:ON:UNK1:C – | 4.81898 | Halogen | Pi-Orbitals | |

| B:GLY384:O – N:UNK1:F | 4.24922 | Halogen | Pi-Pi T-shapedAlkyl | |

| B:TRP383:O – N:UNK1:F | 4.1529 | Halogen | Pi-Alkyl | |

| D6 | ||||

| N:UNK1:H – B:THR377:OG1 | 2.45996 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | -8.5 |

| N:UNK1:C – B:GLN373:OE1 | 3.47128 | Hydrogen Bond | Carbon Hydrogen Bond | |

| B:VAL108:O – N:UNK1:F | 3.66547 | Halogen | Halogen (Fluorine) | |

| B:ASP186:OD1 – N:UNK1:F | 3.3079 | Halogen | Halogen (Fluorine) | |

| B:ASP186:OD1 – N:UNK1:F | 3.09832 | Halogen | Halogen (Fluorine) | |

| B:ASP186:OD2 – N:UNK1:F | 3.128 | Halogen | Halogen (Fluorine) | |

| B:GLN373:CB – N:UNK1 | 3.27526 | Halogen | Pi-Sigma | |

| B:TYR232 – N:UNK1 | 3.61271 | Hydrophobic | Pi-Pi Stacked | |

| B:TYR232 – N:UNK1 | 4.61382 | Hydrophobic | Pi-Pi T-shaped | |

| N:UNK1 – B:TYR232 | 4.76255 | Hydrophobic | Pi-Alkyl | |

| B:TYR232 – N:UNK1:Cl | 5.10267 | Hydrophobic | Pi-AlkylPi-Alkyl | |

|

D5 |

||||

| B:HIS96:HN – N:UNK1:F | 2.0643 | Hydrogen Bond;Halogen | Conventional Hydrogen Bond;Halogen (Fluorine) |

-8.3 |

| N:UNK1 – B:ILE94 | 2.4132 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | |

| B:HIS96:HN – N:UNK1:O | 1.77794 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | |

| B:TYR181:HH – N:UNK1:N | 1.96059 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | |

| B:MET184:HN – N:UNK1:O | 2.00403 | Hydrogen Bond;Halogen | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | |

| N:UNK1:H – B:GLN182:O | 3.23436 | Hydrogen Bond;Halogen | Carbon Hydrogen Bond;Halogen (Fluorine) | |

| B:GLY93:CA – N:UNK1:F | 3.13084 | Hydrogen Bond | Carbon Hydrogen Bond | |

| B:PRO95:CA – N:UNK1:F | 3.31674 | Hydrogen Bond | Carbon Hydrogen Bond | |

| N:UNK1:C – B:GLY384:O | 3.30027 | Halogen | Halogen (Fluorine) | |

| B:TRP88:O – N:UNK1:F | 2.82571 | Halogen | Halogen (Fluorine) | |

| B:TRP88:O – N:UNK1:F | 2.84946 | Halogen | Halogen (Fluorine) | |

| B:GLU89:O – N:UNK1:F | 3.21084 | Halogen | Halogen (Fluorine) | |

| B:GLU89:O – N:UNK1:F | 3.69758 | Halogen | Halogen (Fluorine) | |

| B:ILE94:O – N:UNK1:F | 3.34484 | Halogen | Halogen (Fluorine) | |

| N:UNK1:F | 4.40763 | Hydrophobic | Alkyl | |

| B:PRO321 | 5.01787 | Hydrophobic | Pi-Alkyl | |

| N:UNK1:Cl – | 4.31408 | Hydrophobic | Pi-Alkyl | |

| D1 | ||||

| A:GLN507:NE2 – N:UNK1:O | 2.85862 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond |

-9.0 |

| N:UNK1:H – A:TYR532:OH | 1.87131 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | |

| A:TRP406:CD1 – N:UNK1:N | 3.46597 | Hydrogen Bond |

Conventional Hydrogen Bond | |

| A:GLU404:OE2 – N:UNK1:F | 3.53101 | Halogen | Halogen (Fluorine) | |

| A:TRP535:N – N:UNK1 | 3.9025 | Halogen | Halogen (Fluorine) | |

| A:ALA534:CA – N:UNK1 | 3.80036 | Hydrogen Bond | Pi-Donor | |

| N:UNK1:Cl – A:LYS431 | 3.93906 | Hydrophobic | Pi-Sigma | |

| N:UNK1:C – B:GLY384:O | 3.13084 | Hydrophobic | Alkyl | |

| B:TRP88:O – N:UNK1:F | 3.31674 | Hydrophobic | Pi-Alkyl | |

| B:TRP88:O – N:UNK1:F | 3.30027 | Hydrophobic | Pi-Alkyl | |

|

D3 |

||||

| B:ASP186:OD2 – N:UNK1:F | 3.128 | Halogen | Halogen (Fluorine) | -9.2 |

| B:GLN373:CB – N:UNK1 | 3.27526 | Halogen | Pi-Sigma | |

| B:TYR232 – N:UNK1 | 3.61271 | Hydrophobic | Pi-Pi Stacked | |

| B:TYR232 – N:UNK1 | 4.61382 | Hydrophobic | Pi-Pi T-shaped | |

| B:HIS96:HN – N:UNK1:O | 1.77794 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | |

| B:TYR181:HH – N:UNK1:N | 1.96059 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | |

| B:MET184:HN – N:UNK1:O | 2.00403 | Hydrogen Bond;Halogen | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | |

| N:UNK1:H – B:GLN182:O | 3.23436 | Hydrogen Bond;Halogen | Carbon Hydrogen Bond;Halogen (Fluorine) | |

Conclusion

In this study, we have examined new methods for molecularly docking variations that have been studied over the past ten years. Common mutations that result in resistance which are commonly employed in CADD were also covered. Both the use of molecular docking and its drawbacks were taken into consideration. A strong and practical method for figuring out the binding mechanism of recently created and examined drugs is molecular docking. The ligands Derivative’s1 and Derivative’s 5 had high docking scores with 3LAM (PDB 00003lam) (-9.572 kcal/mol), respectively, out of the 10Triazole derivatives. Furthermore, the pharmacophoric characteristics that underlie their biological action were also disclosed. As a result, these in silico methods have helped identify binding and affinity between 3LAM (PDB 00003lam) enzyme &Triazoles, responsible for anti-viral properties. To ascertain their anti-viral properties, Triazole analogues were docked with 3LAM (PDB 00003lam) enzymes. All of the compounds’ values were discovered to be within the typical range, and Lipinski’s rule of five was not broken. Therefore, it is anticipated that the compounds will have a high oral bioavailability. Structural properties of the compounds are not the only consideration; ease of chemical synthesis, low molecular weight, bioavailability, and stability are also of crucial importance. Compared to commercial products the main advantage of Derivative’s1 and Derivative’s 5 is the ease of chemical synthesis with low molecular weight. Furthermore modification of Derivative’s1 and Derivative’s 5 has a structure that is different to peptidomimetics, which could contribute to its stability and bioavailability. Geometrical structures for the synthesized above drug complexes were computed. The goal of ligand (complex)-protein docking is to predict the predominant binding model(s) of a ligand with a protein of known.

Acknowledgement

The authors are thankful to Dr. S.B. Bhawar, Pravara Rural College of Pharmacy, Pravaranagar.

Funding Sources

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

This statement does not apply to this article.

Ethics Statement

This research did not involve human participants, animal subjects, or any material that requires ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not involve human participants, and therefore, informed consent was not required.

Clinical Trial Registration

This research does not involve any clinical trials.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

Not Applicable

Author Contributions

Rohit Jaysing Bhor: Methodology, Writing and Original Draft.

Mayur Sitaram Gaikwad: Methodology, Writing and Original Draft.

Harshali Narayan Anap: In silico ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity)

Vaishanavi Parashuram Vikhe: In silico ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) by Pyrex Software’s and SWISS ADMET Software

Mayuri Rajendra Dighe: Calculations of Lipinski’s rule of Five and Druglikeness by Pyrex Software’s and SWISS ADMET Software

Harsh Mahesh Kashid: Calculations of Lipinski’s rule of Five and Druglikeness by Pyrex Software’s and SWISS ADMET Software

Nikita Machhindra Jondhale: Docking images of 2D and 3D by Discovery Studio 2021 software

Sakshi Uttam Mulay: by Pyrex Software’s and SWISS ADMET Software

Urmila Suryaji Gaikwad: The active amino residues, bond length, bond category, bond type, ligand energies, and docking scores.

Sunil Eknath Jadhav: The active amino residues, bond length, bond category, bond type, ligand energies, and docking scores.

References

- Sliwoski G, Kothiwale S, Meiler J, Lowe E.W., Computational methods in drug discovery, Rev.2014; 66(2): 334–395.

CrossRef - Song C.M, Lim S.J, Tong J.C, Recent advances in computer-aided drug design, Bioinform,2009; 10(1): 579–591.

CrossRef - Macalino S.J.Y, Gosu V, Hong S, Choi, S, Role of computer-aided drug design in modern drug discovery, Pharm. Res, 2015; 38(2): 1686–1701.

CrossRef - Agostino D, Clematis A, Quarati A, Cesini D, Chiappori F, Milanesi L, Merelli I, Cloud Infrastructures for In Silico Drug Discovery: Economic and Practical Aspects, Biomed Res. Int,2013; 4(4):138-144.

CrossRef - Jorgensen W.L, The Many Roles of Computation in Drug Discovery, Science,2004; 303(4): 1813–1818.

CrossRef - Kapetanovic I.M, Computer-aided drug discovery and development (CADDD): In silico-chemico-biological approach. Chem, Biol. Interact, 2008; 171(1): 165–176.

CrossRef - Kitchen D.B, Decornez H, Furr J.R, Bajorath J, Docking and scoring in virtual screening for drug discovery: methods and applications, Rev. Drug Discov,2004; 3(1): 935–949.

CrossRef - DesJarlais R.L, Sheridan R.P, Dixon J.S, Kuntz I.D, Venkataraghavan R, Docking flexible ligands to macromolecular receptors by molecular shape, Med. Chem,1986; 29(6): 2149–2153.

CrossRef - Levinthal C, Wodak S.J, Kahn P, Dadivanian A.K, Hemoglobin interaction in sickle cell fibers. I: Theoretical approaches to the molecular contacts, Natl. Acad. Sci, 1975;72(1): 1330–1334.

CrossRef - Goodsell D.S, Olson A.J, Automated docking of substrates to proteins by simulated annealing, Proteins, 1990; 8(1): 195–202.

CrossRef - Salemme F.R, An hypothetical structure for an intermolecular electron transfer complex of cytochromes c and b5, Mol. Biol.,1976; 102(1): 563–568.

CrossRef - Wodak S.J, Janin J, Computer analysis of protein-protein interaction, Mol. Biol.,1978; 124(3): 323–342.

CrossRef - Kuntz I.D, Blaney J.M, Oatley S.J, Langridge R, Ferrin T.E, A geometric approach to macromolecule-ligand interactions, Mol. Biol.,1982; 161(2): 269–288.

CrossRef - Kuhl F.S, Crippen G.M, Friesen D.K, A combinatorial algorithm for calculating ligand binding, Comput. Chem,1984; 5(1): 24–34.

CrossRef - DesJarlais R.L, Sheridan R.P, Seibel G.L, Dixon J.S, Kuntz I.D, Venkataraghavan R, Using shape complementarity as an initial screen in designing ligands for a receptor binding site of known three-dimensional structure, Med. Chem,1988; 31(4): 722–729.

CrossRef - Warwicker J, Investigating protein-protein interaction surfaces using a reduced stereochemical and electrostatic model, Mol. Biol,1989; 206(2): 381–395.

CrossRef - Jiang F, Kim S.H, “Soft docking”: Matching of molecular surface cubes, Mol. Biol,1991; 219(1): 79–102.

CrossRef - Meng X.Y, Zhang H.X, Mezei M, Cui M, Molecular docking: A powerful approach for structure-based drug discovery, Comput, Aided. Drug Des,2011; 7(4): 146–157.

CrossRef - Amaro R.E, Baudry J, Chodera J, Demir Ö, McCammon J.A, Miao Y, Smith J.C, Ensemble Docking in Drug Discovery, J.,2018; 11(4): 2271–2278.

CrossRef - Abagyan R, Totrov M, High-throughput docking for lead generation, Opin. Chem. Biol.,2001; 5(3): 375–382.

CrossRef - Carlson H.A, Protein flexibility and drug design: how to hit a moving target, Opin. Chem. Biol, 2002;6(11): 447–452.

CrossRef - Frieden TR, Das-Douglas M, Kellerman SE, Henning KJ.Applying public health principles to the HIV epidemic, N Engl J Med., 2005; 353 (22):2397-2402.

CrossRef - Sogolow E, Peersman G, Semaan S, Strouse D, Lyles CM, The HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis Project: scope, methods, and study classification results, J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2002; 30 (suppl 1): S15-S29.

CrossRef - Scofield JM, Smith RA, Implications of the HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis Project for the efforts of state, territorial, and local health departments, J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2002; 30(suppl 1): S134-S136.

CrossRef - Johnson WD, Hedges LV, Ramirez G, HIV prevention research for men who have sex with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2002; 30(suppl1): S118-S129.

CrossRef - Mullen PD, Ramírez G, Strouse D, Hedges LV, Sogolow E, Meta-analysis of the effects of behavioral HIV prevention interventions on the sexual risk behavior of sexually experienced adolescents in controlled studies in the United States, J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2002; 30(suppl 1): S94-S105.

CrossRef - Neumann MS, Johnson WD, Semaan S, Review and metaanalysis of HIV prevention intervention research for heterosexual adult populations in the United States, J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2002; 30(suppl 1): 106-S117.

CrossRef - Semaan S, Des Jarlais DC, Sogolow E, A meta-analysis of the effect of HIV prevention interventions on the sex behaviors of drug users in the United States, J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2002; 30(suppl 1):S73-S93.

CrossRef - Semaan S, Kay L, Strouse D, A profile of U.S.-based trials of behavioral and social interventions for HIV risk reduction, J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2002; 30(suppl 1):S30-S50.

CrossRef - Herbst JH, Sherba RT, Crepaz N, A meta-analytic review of HIV behavioral interventions for reducing sexual risk behavior of men who have sex with men, J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39(2):228-241.

- Passin WF, Kim AS, Hutchinson AB, A systematic review of HIV partner counseling and referral services: client and provider attitudes, preferences, practices, and experiences, Sex Transm Dis, 2006;33(5):320-328.

CrossRef - Crepaz N, Horn AK, Rama SM, The efficacy of behavioural interventions in reducing HIV risk sex behaviors and incident sexually transmitted disease in Black and Hispanic sexually transmitted disease clinic patients in the United States: a meta-analytic review, Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34(6):319-332.

CrossRef - Herbst JH, Beeker C, Mathew A, The effectiveness of individual-, group-, and community-level HIV behavioural risk-reduction interventions for adult men who have sex with men: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(4 suppl):38-67.

CrossRef

Abbreviations:

mg/kg: Milligram/ kilograms; Sec: seconds; Kcal: kilocalorie; Mol.Wt: Molecular Weight; Gm: Gram; LEU: Leucine; THR: Threonine; ALA: Alanine; MET: Methionine; PHE: Phenylalanine; WHO: World health association; Log P: partition coefficient

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.