Manuscript accepted on : 27-05-2025

Published online on: 18-06-2025

Plagiarism Check: Yes

Reviewed by: Dr. Gandham Rajeev

Second Review by: Dr Sunil Chaudhry

Final Approval by: Dr. Mohd. Fareed

Vasundhara Sawant1* , Sanjay Sawant1

, Sanjay Sawant1 , Prerna Tamte1

, Prerna Tamte1 , Minal Ghante2

, Minal Ghante2 and Jyoti Tangde1

and Jyoti Tangde1

1Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, STES, Smt. Kashibai Navale College of Pharmacy, Kondhwa (Bk.), Savitribai Phule Pune University, Pune, Maharashtra.

2Department of Quality Assurance, STES, Smt. Kashibai Navale College of Pharmacy, Kondhwa (Bk.), Savitribai Phule Pune University, Pune, Maharashtra

Corresponding Author E-mail:pr.vasundhara@gmail.com

DOI : http://dx.doi.org/10.13005/bbra/3390

ABSTRACT: Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus is significantly affected by gluconeogenesis mediated glucose production. Various enzymatic targets and receptors are responsible in pathogenesis of diabetes and obesity. Despite many drugs are available to treat this condition but there is need to explore various natural bioactive molecules with appropriate potency and safety. The present investigation focuses on the multi-targeted activity of bioactive phytoconstituents of Glycine max (soybean) using computational approach. All the phytoconstituents were screened for drug-likeness and ADMET properties, among which 26 were considered for further studies. The binding affinity and interaction patterns within the active site of the enzymes was assessed with molecular docking study. Four key hydrogen bonds were identified between phytochemicals and allosteric amino acid residues through docking analysis. The hydrogen bonds included LYSB542 at 2.08 Å, ARG527 at 2.43 Å, GLU551 at 2.54 Å, and LYSD542 at 3.28 Å. Besides, the interactions were found hydrophobic in nature. This may inhibit the enzymes and stabilize it at the active binding pocket. The superior binding affinity of Genistein, Taraxerol, and β-Amyrin against the reference compounds make it very promising. Therefore, this indicates that it is a useful drug for T2DM and obesity management. Genistein was tested for in-vitro enzyme assay and exhibited comparable enzyme inhibition with standard acarbose. Computational studies shows that phytochemicals like Genistein derived from Glycine max are useful in the management of T2DM and found to be safe through in-silico studies. However, further experimental validation is needed to determine the safety and efficacy. Glycine max may provide potential therapeutic compounds for treatment of obesity and diabetes.

KEYWORDS: Diabetes; Glycine max (G. Max);In-silico;In-vitro; Obesity; Phytochemicals

Download this article as:| Copy the following to cite this article: Sawant V, Sawant S, Tamte P, Ghante M, Tangde J. Exploring the Multi-targeted Therapeutic Mechanism of Bioactives from Glycine max in Treatment of type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Obesity through an In-vitro and In-silico Approach. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(2). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Sawant V, Sawant S, Tamte P, Ghante M, Tangde J. Exploring the Multi-targeted Therapeutic Mechanism of Bioactives from Glycine max in Treatment of type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Obesity through an In-vitro and In-silico Approach. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(2). Available from: https://bit.ly/4n8wKWv |

Introduction

Obesity, a metabolic disorder involving excessive accumulation of fat in adipose tissue poses significant risk of health issues such as diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. This condition arises from a complex interplay of genetic, behavioural and environmental factors. According to World Health Organization (WHO) report 2022, around 2.5 billion people were obese globally.1 Obesity is one of the most reported and significant risk factors for many metabolic and chronic diseases.2 It’s pathophysiology is linked to a spectrum of disorders3 like cancer,4 diabetes mellitus,5 osteoarthritis,6 and coronary heart disease.6,7

Obesity leads to hormonal, inflammatory, and metabolic alterations that act on numerous organs and increase disease risk.9 Obesity is strongly associated with type 2 diabetes (T2DM), cancer, and cardiovascular disease, which usually result from unhealthful lifestyles such as lack of exercise and excessive calorie consumption.10 Approximately 60%–90% of individuals with T2DM have obesity. Obesity not only increases the risk but may directly cause T2DM by disrupting metabolic balance. T2DM is caused by insulin resistance when β-cells do not effectively respond to the signals of insulin.11 Type 1 diabetes, on the other hand, results from the lack of function in β-cells in the pancreas to release insulin.12 Both types lead to high blood sugar and long-term damage to the eyes, kidneys, liver, and nerves. Understanding how obesity causes T2DM is important for improving treatment and prevention.13–15

T2DM results due to peripheral insulin resistance and insulin insufficiency.16,17 This disease results from the failure of pancreatic β-cells to produce adequate amount of insulin. 18 Most allopathic drugs employed for the treatment of T2DM possess some side effects particularly in pregnancy and polypharmacy.19

Consequently, natural agents or phytochemicals could serve as a promising alternative to treat such conditions with minimal side effects and multi-targeted or synergistic effects. 20,21 Numerous research work has demonstrated the potential of Glycine max or soybean, in traditional medicine for management of diabetes.22–26 Since long, this plant serves as a significant source of protein, and regular use of this grain is thought to lower the incidence of T2DM globally. Phytochemicals of this plant primarily contains isoflavones, protein, carbohydrates, and lipid fractions.27 Despite the nutritional and pharmacological values, mechanistic study and role in pathogenesis and obesity is not yet explored.

Hence the current study is focused to predict the mechanism and binding interactions of various phytochemicals from Glycine max with multiple proteins associated with diabetes and obesity treatment.

Aim: This research work is carried out to predict the mechanism of action and binding interactions of various phytochemicals from Glycine max with multiple targets associated with the treatment of diabetes and obesity to facilitate future drug development.

Objectives

During this study, in-silicoADME,28 drug-likeness and toxicity profile of secondary metabolites of Glycine max were tested. 29,30 Further the enzyme inhibition assay was also performed for better understanding of the biological effect.

Materials and Methods

Phytochemical structures were obtained from the IMPPAT (Indian Medicinal Plants, Phytochemistry, and Therapeutics) database that contains information regarding Indian medicinal plants.22 The structure of ligands was downloaded as SDF and processed with Biovia Discovery Studio. They were optimized with MMFF94 force field to ensure that they were in stable conformation.31 They were then stored as PDB files. Later, they were converted to the PDBQT format for compatibility with AutoDock. This setup supports docking simulations by allowing flexibility of the ligand and correct assignment of charges. Polar hydrogens were appended, and Gasteiger charges were used. AutoDock utilized grid-based estimations of binding energies. Docking was conducted to examine ligand-protein target interactions.32 All the steps were performed under standard procedures to minimize deviation and ensure reproducibility. Information concerning active site and phytochemical structures is provided in the supplementary file.

ADMET and drug likeness study

The development and identification of new pharmaceuticals heavily depend on the evaluation of ADMET parameters. These parameters are critical in assessing the pharmacokinetic properties and overall safety profile of potential drug candidates. Efficacy and safety assessments, combined with knowledge of chemical interactions between phytochemicals and the active site of proteins are of great importance in determining their therapeutic potential. However, most of the phytochemicals fail at the clinical trial stage, mainly due to suboptimal drug-likeness scores, which are often because of poor pharmacokinetic properties. Therefore, in-depth knowledge of pharmacokinetics is crucial in the drug development process, helping to choose a suitable candidate for further clinical evaluation and ultimately therapeutic application. Hence, ADMET properties were studied using webtools28,33 such as ADMETlab 2.0 and Swiss ADME. Several ADMET characteristics had been predicted for each ligand including lead likeness, drug likeness, NHBD, MolLogP, MolLogS and Lead likeness, synthetic accessibility, GI absorption, BBB permeability, Coco2 permeability, HERG 1 inhibitors and pkCSM. In addition, toxicity parameters considered during screening of the phytochemicals involve T. Pyriformis toxicity, AMES toxicity, oral rat acute toxicity, hepatotoxicity, minnow toxicity, carcinogenicity and maximum tolerated dose.

Evaluation of in-vitro enzyme assay

The in-vitro enzyme inhibition was determined using α-amylase assay. To constitute the α-amylase stock solution (1000 µg/mL), 2.5 mg of α-amylase was dissolved in 100 mL of 20mM Na3PO4 buffer with 6 mM NaCl. Further, 0.035 g of NaCl, 0.283 g Na2HPO4, and 0.239 g of sodium dihydrogen phosphate (NaH2PO4) were dissolved in distilled water (100 mL) and the pH was adjusted to 7.0. The 100 ml iodine solution (1%) was made by dissolving 1 g of iodine & 2 g of potassium iodide in distilled water, while a starch solution was made by dissolving 1 g powdered starch in 100 mL distilled water.

A 100 µg/mL concentration was prepared by dissolving a concentration of 0.001 g of the sample extract in dimethyl sulfoxide and making it up to a volume of 10 mL with the help of dimethyl sulfoxide. Acarbose at the same concentration used as the reference standard. To carry out the enzyme assay, 1 mL of test solution (100 µg/mL) was added to 1 mL of α-amylase stock solution. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 10 minutes to allow initial interaction between the enzyme and the sample. After the initial incubation, 1 mL of 1% starch solution was added to the solution, which was then further incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. Subsequently, 1 mL of 1% iodine solution and 5 mL of distilled water were added to the reaction mixture, followed by absorbance measurement at 565 nm using a UV-Visible spectrophotometer.

Similar process was used to prepare the control samples, with the exception that distilled water was used in place of the starch solution. The following formula was then used to calculate the percentage inhibition of α-amylase activity.

Inhibition (%) = {(A – C)/C} × 100, where A is the sample’s absorbance and C is the control’s absorbance (starch-free). As part of its evaluation as an antidiabetic activity, this assay provided information on the test sample’s capacity to suppress α-amylase activity.

Results

This research work involves understanding various interactions of phytochemicals from Glycine max with biological targets associated with metabolic disorders. Tested phytochemicals primarily includes Genistein, Taraxerol, β-Amyrin, Dammaradienol, Cycloartanol, Calendol, Simiarenol, 24-Methylenecycloartanol, Lanosterol, Eburicol, Euphol, Tirucallol and Cyclobranol. The interactions were analysed using molecular docking approach. Toxicity predictions and drug-likeness evaluations were carried out to determine their safety and therapeutic potential. Results of the study has given insights into the binding affinities and possible mechanisms of action. Total 26 phytochemicals from Glycine Max were studied by molecular docking approach against 9 different therapeutic target proteins of T2DM and obesity. The binding energy and significant interactions were represented in Table 1. Among all the phytochemicals Genistein, Taraxerol and β-Amyrin have shown better binding interactions with all the target proteins resulting in good binding energies. This suggest that these three phytochemicals are able to exert antidiabetic and anti-obesity effects via multiple mechanistic pathways.

Table 1: Binding Energy and mode of Interaction of each Ligands with each Targets

|

Ligand |

Target Proteins |

||||||||

|

α-Amylase |

Suppressor |

Cholesteryl |

C-Jun N- |

Lamin A/C |

Human |

α- |

Peroxisome |

Adiponectin |

|

|

(-)-Butyrospermol |

-9.1 |

-7.6 |

-9.9 |

-6.8 |

-10.1 |

-11.4 |

-8.6 |

-10.9 |

-6.0 |

|

Dammaradienol |

-9.8 |

-8.0 |

-10.1 |

-6.6* |

-10.1* |

-9.5 |

-10.2 |

-10.9 |

-6.7* |

|

Cycloartanol |

-9.0 |

-7.6 |

-9.8 |

-7.3 |

-10.9** |

-11.0* |

-7.5* |

-9.9 |

-7.0 |

|

Calendol |

-9.8* |

-8.9 |

-11.4 |

-8.0* |

-8.2* |

-10.1* |

-9.1 |

-11.5 |

-7.2 |

|

Genistein |

-9.4$ |

-8.0 |

-9.9*** |

-9.5 |

-9.7# |

-10.3 |

-8.9 |

-10.6* |

-7.0$ |

|

Simiarenol |

-9.6 |

-9.2 |

-11.0 |

-6.9 |

-12.1 |

-9.7 |

-8.1* |

-10.1 |

-7.2 |

|

24-Methylenecycloartanol |

-9.8 |

-7.9 |

-10.6 |

-6.3 |

-9.9 |

-10.5 |

-9.8 |

-9.9 |

-6.1 |

|

α-Amyrin |

-10.4 |

-9.2 |

-11.5 |

-7.7 |

-8.2 |

-10.4 |

-9.1 |

-11.6 |

-7.3 |

|

Taraxerol |

-10.6 |

-9.2 |

-11.7 |

-8.3* |

-8.3 |

-9.7* |

-9.7 |

-10.3 |

-7.3 |

|

Eburicol |

-9.7 |

-8.1 |

-10.4 |

-6.6* |

-8.4* |

-9.7 |

-9.9 |

-11.0 |

-5.8 |

|

Euphol |

-8.9 |

-7.5 |

-10.0 |

-6.4 |

-9.9 |

-10.2 |

-8.8 |

-11.0 |

-6.7 |

|

Tirucallol |

-9.0 |

-7.4 |

-10.6 |

-6.7 |

-10.1* |

-11.4 |

-9.8 |

-10.9* |

-6.0 |

|

Lanosterol |

-9.2 |

-7.4 |

-10.7 |

-6.7 |

-9.3* |

-9.4 |

-9.5 |

-11.7 |

-6.7* |

|

β-Amyrin |

-9.8 |

-9.0 |

-11.7 |

-8.2* |

-8.1 |

-10.2 |

-9.0 |

-10.5 |

-7.3 |

|

Cyclobranol |

-10.3 |

-7.6 |

-11.1 |

-6.7 |

-9.8** |

-11.5* |

-10.4 |

-10.5 |

-6.0 |

(* = 1 H-bond, $= 4 H-Bonds, # = 5 H-bonds, *** = 3-H-Bonds & ** =2 H-Bonds)

A detailed comparison of drug-likeness properties for each phytochemical, including parameters such as molecular weight, the number of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, MolLogP (a measure of lipophilicity), and MolLogS (a measure of solubility), is presented in Table 2, providing insights into their relative suitability as drug candidates. Of three phytochemicals with good binding affinity, only Genistein has shown less violations for drug likeness properties. Genistein has not shown any BRENK or PAINS alerts and hence it can be considered as potential compound for further drug development.

Table 2: Ligand molecule with their molecular formula, Lipinski, Drug likeliness score

|

Compounds |

Molecular |

DLS

|

Mol LOGP |

Mol. Vol (A3) |

PAINS |

Brenk |

Lead likeness |

Synthetic |

||||

|

Lipinski |

Ghose |

Veber |

Egan |

Muegge |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

(-)-Butyrospermol |

426.72 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

6.82 |

496.727 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

6.15 |

|

Dammaradienol |

426.72 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

6.82 |

496.727 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

5.85 |

|

Cycloartanol |

428.73 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

7.07 |

493.444 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

6.22 |

|

Calendol |

426.72 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

4.93 |

490.807 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

6.17 |

|

Genistein |

432.38 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

-1.61 |

404.357 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

5.12 |

|

Simiarenol |

426.72 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

6.92 |

490.807 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

6.34 |

|

24-Methylenecycloartanol |

440.74 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

7.12 |

508.103 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

6.36 |

|

α-Amyrin |

426.72 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

6.92 |

490.807 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

6.17 |

|

Taraxerol |

426.72 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

6.92 |

490.807 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

6.04 |

|

Eburicol |

440.74 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

7.01 |

514.023 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

6.19 |

|

Euphol |

426.72 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

6.82 |

496.727 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

6.07 |

|

Tirucallol |

426.72 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

6.82 |

496.727 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

6.07 |

|

Lanosterol |

426.72 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

6.82 |

496.727 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

6.07 |

|

β-Amyrin |

426.72 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

6.92 |

490.807 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

6.04 |

|

Cyclobranol |

440.74 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

7.12 |

508.103 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

6.64 |

For the pharmacokinetic properties various parameters were studied including human intestinal absorptivity, caco2 permeability, blood brain barrier, Ames’s toxicity, maximum tolerated dose, hERG1 toxicity, oral rat toxicity, hepatotoxicity, T. Pyriformis toxicity, minnow toxicity explained in Table 3. These results indicates that Genistein is not associated with AMES toxicity, hERG-1 inhibition or hepatotoxicity. Overall toxicity results indicate the safety of this phytochemical among others.

Table 3: Toxicity prediction

|

Compound

|

Caco2 permeability |

BBB permeability |

AMES toxicity |

hERG 1 inhibitor |

Oral Rat Acute Toxicity (LD50) |

Hepato toxicity |

T. pyriformis toxicity |

Minnow toxicity |

Carcinogenicity

|

|

(-)-Butyrospermol |

1.217 |

0.723 |

No |

No |

0.808 |

No |

0.578 |

-1.896 |

0.05 |

|

Dammaradienol |

1.232 |

0.751 |

No |

No |

0.885 |

No |

0.408 |

-2.144 |

0.012 |

|

Cycloartanol |

1.218 |

0.833 |

No |

No |

2.674 |

No |

0.361 |

-2.306 |

0.048 |

|

Calendol |

1.232 |

0.698 |

No |

No |

0.82 |

No |

0.364 |

-1.65 |

0.013 |

|

Genistein |

0.464 |

-1.338 |

No |

No |

3.439 |

No |

0.285 |

0.94 |

0.414 |

|

Simiarenol |

1.268 |

0.731 |

No |

No |

2.529 |

No |

0.351 |

-2.202 |

0.118 |

|

24-Methyl-enecycloartanol |

1.208 |

0.843 |

No |

No |

2.622 |

No |

0.297 |

-2.262 |

0.071 |

|

α-Amyrin |

1.238 |

0.693 |

No |

No |

2.217 |

No |

0.398 |

-1.497 |

0.012 |

|

Taraxerol |

1.232 |

0.679 |

No |

No |

2.311 |

No |

0.378 |

-1.54 |

0.008 |

|

Eburicol |

1.218 |

0.724 |

No |

No |

1.987 |

No |

0.639 |

-2.057 |

0.017 |

|

Euphol |

1.197 |

0.676 |

No |

No |

1.848 |

No |

0.755 |

-1.685 |

0.168 |

|

Tirucallol |

1.197 |

0.676 |

No |

No |

1.848 |

No |

0.755 |

-1.685 |

0.247 |

|

Lanosterol |

1.197 |

0.676 |

No |

No |

1.848 |

No |

0.755 |

-1.685 |

0.018 |

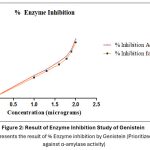

The enzyme inhibition studies for α-amylase shows that Genistein is almost equally potent inhibitor compared with standard drug acarbose.

Discussion

Suppressor of cytokine signalling 3 (SOCS3) is a member of the SOCS protein family and functions as a negative regulator of insulin signalling in insulin-sensitive tissues such as adipocytes and hepatocytes.34 Of all the screened phytoconstituents, only β-amyrin presented significant alkyl interactions with PRO (A: 105), with score – 9.0 kcal/mol as depicted in Figure 1. The docking scores of simiarenol and α-amyrin with SOCS3 were found to have the highest binding affinities, with both achieving -9.2 kcal/mol. In addition, simiarenol also showed alkyl interactions with TRP (A:1369).35

Cholesteryl Ester Transfer Protein (CETP) has significant physiological roles to protect against diet-induced insulin resistance.36 Genistein gives substantial interactions with SER (A:191), MET (A:194) and SER (A:230) of CETP; while binding energy was found to be -9.2 Kcal/mol as depicted in Figure 1. Taraxerol and β-amyrin also exhibited good binding energies of -11.7 kcal/mol each with Cholesteryl Ester Transfer Protein however, these are not stabilized through conventional hydrogen bonding interactions.37,38

C-Jun N-terminal Kinase 1 (JNK-1)39 drives obesity by various mechanistic pathways which includes: direct phosphorylation of IRS 1 and 2; improving the inflammation, metabolism and adiposity via inhibition of TSH; and controlled regulation of the PPAR-α-FGF21 axis. Calendol, Dammaradienol, Eburicol and Taraxerol shows conventional hydrogen bonding interactions with target protein C-Jun N-terminal Kinase 1 via key amino acid residues like ARG (A:127) in addition to hydrophobic interactions with CYS (A:163), TYR (A:130) and TRP (A: 324) in Figure 1. Genistein showed the highest binding affinity with this protein.

|

Figure 1: Interactions of few representative bioactives with an active site of various targets of Diabetes and Obesity

|

Good binding affinity was observed by cycloartanol at a docking score of -11.0 kcal/mol; it formed two hydrogen bonds with Lamin A/C through SER (A:302), as shown in Figure 1. It was found that (-)-butyrospermol and tirucallol possess highest binding energies of all the phytochemicals tested against all the targeted proteins through molecular docking studies.40 Lamin A/C has a hydrophobic pocket at an active site.41 Calendol, Cyloartanol, Cyclobranol, Dammaradienol, Eburicol, Genistein, Lanosterol and Tirucallolare found to be stable at an active site pocket due to strong hydrophobic network.

Hydrogen bonding interactions were observed between cycloartenol and cyclobranol with the SER(A:302) of the human aldose reductase. Moreover, cycloartenol and cyclobranol showed the highest binding energy of -11.0 kcal/mol and -11.5 kcal/mol with this target. Cycloartenol, cyclobranol, and taraxerol had notable π-π stacking with the human aldose reductase enzyme’s active site. These include CYS (A:298), TYR (A:209), TYR (A:48) and PHE (A:122). Besides the π-π stacking, the compounds showed C-H bonding interactions with TRP (A:111) and SER (A:302). The other phytochemicals did not show any remarkable interactions with human aldose reductase. This shows that the glucose-lowering mechanism does not apply for these.42

Noteworthy interactions were not observed for phytochemicals of Glycine max with an active site of α-glucosidase enzyme. Only amino acids involved in this association are TRP (A:1369) and SER (A:1292) as shown in Figure 1 for cycloartenol and Simiarenol whereas binding energy score lies in the range of -8.1 Kcal/mol. This is suggestive that the antidiabetic effect of these phytochemicals may not be exerted by this mechanism.43

Among the compounds tested, the highest interactions at multiple targets were recorded for Genistein, Taraxerol, and β-Amyrin. Genistein have shown binding interactions with α-Amylase (-9.4 kcal/mol), Cholesteryl Ester Transfer Protein (-9.9 kcal/mol) and Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-γ (-10.6 kcal/mol) suggesting its use in carbohydrate metabolism and lipid regulation. It is involved in the formation of network with multiple hydrogen bonds that stabilized its structure in the binding pocket. In addition, Genistein was found to have a good safety profile with No AMES toxicity and moderate Caco-2 permeability. At the same time, Taraxerol and β-Amyrin demonstrated strong binding affinities. They possess strong interactions with C-Jun N-terminal Kinase, Lamin A/C and Human Aldose Reductase. These interactions indicate their function to reduce inflammation and treat complications of diabetes. Both compounds had good pharmacokinetic properties, demonstrated by scores of synthetic accessibilities of 6.04 for β-Amyrin and 6.17 for Taraxerol. This makes them feasible candidates to begin developing them as drugs.44

Dammaradienol, Cycloartanol, and Calendol possess low binding affinities with various target proteins. The compound Dammaradienol had high affinity for Adiponectin (-10.9 kcal/mol) and α-Glucosidase (-10.2 kcal/mol), indicating the potential to act as an antidiabetic agent. Cycloartanol showed good interaction with Lamin A/C (-11.0 kcal/mol) and Human Aldose Reductase (-7.5 kcal/mol), suggesting the involvement in metabolic regulation. However, these compounds had low bioavailability and permeability. Calendol demonstrated mild inhibition against α-Amylase (-9.8 kcal/mol) and PPAR-γ (-11.5 kcal/mol). High LogP value at 4.93 limits the availability of this compound in humans. Genistein exhibited strong network of conventional hydrogen bonds with adiponectin via ARG (A:413), PRO (A:411), THR (A:415) and GLU (A:402). Also, it is stabilized at an active site with various hydrophobic interactions with ILE (A:407) and MET (A:410) as depicted in Figure 1.

Simiarenol, 24-Methylenecycloartanol, and Lanosterol showed weaker binding affinities and less favourable drug-like properties. Simiarenol was shown to interact with Lamin A/C (-12.1 kcal/mol) and α-Glucosidase (-10.1 kcal/mol), but it has poor solubility and low permeability (Caco-2: 1.268). 24-Methylenecycloartanol exhibited moderate binding to several targets but lack the strong hydrogen bonding. Lanosterol showed weak interaction across most of the targets. The highest was -11.7 kcal/mol against Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-γ. Due to low drug-likeness score, weak blood-brain barrier permeability, and lower affinity for other targets, the drug-likeness value is reduced.

The least promising results were from Eburicol, Euphol, Tirucallol, and Cyclobranol. Their binding energies varied from -9.0 to -10.6 kcal/mol. The compounds had weak hydrogen bond network compared to the top-scoring phytochemicals. Pharmacokinetic properties were suboptimal and included decreased permeability and risk of hepatotoxicity.45

Genistein, Taraxerol, and β-Amyrin are the top hit compounds from this study. Genistein is top ranking phytochemical based on binding affinity, drug likeness and in-silico ADMET studies. It has a strong binding affinity with key metabolic targets, including α-Amylase (PDB ID: 1B2Y, -9.4 kcal/mol), CETP (PDB ID: 2OBD, -9.9 kcal/mol), and PPAR-γ (PDB ID: 4CI5, -10.6 kcal/mol). It also forms multiple hydrogen bonds, making it a stable drug candidate. Genistein’s drug-likeness is excellent, as it follows Lipinski, Ghose, Veber, Egan, and Muegge rules. It’s LogP (-1.61) and LogS (-3.18 mg/L) indicate good solubility and absorption. Toxicity studies confirm that Genistein is safe, with no AMES toxicity, good Caco-2 permeability (0.464), and no hepatotoxicity or carcinogenicity risks. Taraxerol and β-Amyrin also showed strong binding interactions with multiple targets, especially JNK-1, Lamin A/C, and Human Aldose Reductase. They have high binding scores (-11.7 kcal/mol for β-Amyrin with CETP, -10.3 kcal/mol for Taraxerol with Adiponectin) and good drug-likeness parameters. However, Genistein ranks the highest due to its superior safety, drug-likeness, and metabolic target binding.46

Drug likeness properties of selected ligands

Among the screened phytochemicals, Genistein is found to fulfil most of the drug-likeness rules such as Lipinski’s rule of five, Veber’s rule, and Muegge’s criteria. Calendol has good physicochemical properties, such as an optimal molecular weight, two hydrogen bond acceptors, and one hydrogen bond donor. These properties suggest a good pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics profile, thus making it a promising compound for further development. Toxicity studies indicate that Genistein does not exhibited any Brenk or PAINS alerts and was found to be comparatively safe among all other phytochemicals. AMES toxicity and blood brain barrier permeation was also found satisfactory for Genistein.

Enzyme Inhibition Study

Genistein (100 μg/mL) from G. max have inhibited 75.3% of α-amylase activity with an IC50 values 32.08 ± 3.50 μg/mL. Whereas, at the same concentration Acarbose, the reference standard has shown 79.6% inhibitory effect and IC50 value was found to be 28.79 ± 4.01 μg/mL. However, these results suggest that Genistein is almost equipotent with the standard drug. (Figure 2).

|

Figure 2: Result of Enzyme Inhibition Study of Genistein

|

Conclusion

The current investigation demonstrates that certain natural molecules from Glycine max (soybean) can be used to treat metabolic disorders. The promising results were exhibited by three molecules Genistein, Taraxerol, and β-Amyrin. Genistein had strong binding affinity with α-Amylase (PDB ID: 3RX2, -9.4 kcal/mol), Cholesteryl Ester Transfer Protein (CETP, PDB ID: 2OBD, -9.9 kcal/mol), and Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-γ (PPAR-γ, PDB ID: 3DZY, -10.6 kcal/mol). Taraxerol was strongly interacting with C-Jun N-terminal Kinase 1 (JNK-1, PDB ID: 4IZY, -8.3 kcal/mol) and Lamin A/C (PDB ID: 1IFR, -9.7 kcal/mol). β-Amyrin interacted very well with Human Aldose Reductase (PDB ID: 1US0, -10.5 kcal/mol). This implies that it can possibly aid in regulating diabetic issues, obesity and reduce inflammation. These molecules are safe, well absorbed, possess good drug-like character and are natural. Hence, further studies on Genistein shall provide novel treatment regimens for obesity and type 2 diabetes with multi-targeted approach.

Acknowledgement

The author is profoundly grateful to STES’s Smt. Kashibai Navale College of Pharmacy, Pune for providing facilities to conduct the work

Funding Sources

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

This statement does not apply to this article.

Ethics Statement

This research did not involve human participants, animal subjects, or any material that requires ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not involve human participants, and therefore, informed consent was not required.

Clinical Trial Registration

This research does not involve any clinical trials.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

Not Applicable

Author Contributions

Vasundhara Sawant: Conceptualization, Analysis, Methodology and Visualization.

Sanjay Sawant: Supervision.

Prerna Tamte: Data Collection, Writing – Review & Editing, Writing – Original Draft.

Minal Ghante: Supervision.

References

- Malone JI, Hansen BC. Does obesity cause type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM)? Or is it the opposite? Pediatr Diabetes. 2019; 20(1):5–9.

CrossRef - Colditz GA, Peterson LL. Obesity and Cancer: Evidence, Impact, and Future Directions. Clin Chem. 2018; 64(1):154–62.

CrossRef - Ruze R, Liu T, Zou X, Song J, Chen Y, Xu R. Obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus: connections in epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatments. Front Endocrinol. 2023;14:1161521.

CrossRef - Cox TR. The matrix in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2021;21(4):217–38.

CrossRef - Antar SA, Ashour NA, Sharaky M, Khattab M, Ashour NA, Zaid RT. Diabetes mellitus: Classification, mediators, and complications; A gate to identify potential targets for the development of new effective treatments. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023; 168: 115734.

CrossRef - Schett G, Kleyer A, Perricone C, Sahinbegovic E, Iagnocco A, Zwerina J. Diabetes Is an Independent Predictor for Severe Osteoarthritis. Diabetes Care. 2013; 36(2): 403–9.

CrossRef - Bax JJ, Young LH, Frye RL, Bonow RO, Steinberg HO, Barrett EJ. Screening for Coronary Artery Disease in Patients With Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007; 30(10): 2729–36.

CrossRef - Magnusson K, Hagen KB, Østerås N, Nordsletten L, Natvig B, Haugen IK. Diabetes Is Associated With Increased Hand Pain in Erosive Hand Osteoarthritis: Data From a Population‐Based Study. Arthritis Care Res. 2015; 67(2):187–95.

CrossRef - Deng T, Lyon CJ, Bergin S, Caligiuri MA, Hsueh WA. Obesity, Inflammation, and Cancer. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis. 2016;11(1):421–49.

CrossRef - Aamir AH, Ul-Haq Z, Fazid S, Shah BH, Raza A, Jawa A. Type 2 diabetes prevalence in Pakistan: what is driving this? Clues from subgroup analysis of normal weight individuals in diabetes prevalence survey of Pakistan. Cardiovasc Endocrinol Metab. 2020; 9(4):159–64.

CrossRef - Adnan M, Aasim M. Prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus in Pakistan: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2024; 24(1):108.

CrossRef - Carvalho LA, Gerdes JM, Strell C, Wallace GR, Martins JO. Interplay between the Endocrine System and Immune Cells. BioMed Res Int. 2015; 2015:1–2.

CrossRef - Deng D, Evans T, Mukherjee K, Downey D, Chakrabarti S. Diabetes-induced vascular dysfunction in the retina: role of endothelins. Diabetologia. 1999; 42(10):1228–34.

CrossRef - Park CW. Diabetic Kidney Disease: From Epidemiology to Clinical Perspectives. Diabetes Metab J. 2014; 38(4):252.

CrossRef - Mohamed J, H. Mechanisms of Diabetes-Induced Liver Damage: The role of oxidative stress and inflammation. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2016; 16(2): e132-141.

CrossRef - Jansson P ‐A. Endothelial dysfunction in insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. J Intern Med. 2007; 262(2):173–83.

CrossRef - Lei X, Zhou Q, Wang Y, Fu S, Li Z, Chen Q. Serum and supplemental vitamin D levels and insulin resistance in T2DM populations: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Sci Rep. 2023; 13(1):12343.

CrossRef - Dludla PV, Mabhida SE, Ziqubu K, Nkambule BB, Mazibuko-Mbeje SE, Hanser S. Pancreatic β-cell dysfunction in type 2 diabetes: Implications of inflammation and oxidative stress. World J Diabetes. 2023; 14(3):130–46.

CrossRef - Kazi AA, Blonde L. Classification of diabetes mellitus. Clin Lab Med. 2001; 21(1):1–13.

CrossRef - Prabhu S, Vijayakumar S. Antidiabetic, hypolipidemic and histopathological analysis of Gymnema sylvestre (R. Br) leaves extract on streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Biomed Prev Nutr. 2014; 4(3):425–30.

CrossRef - El-Sayed MIK. Effects of Portulaca oleracea L. seeds in treatment of type-2 diabetes mellitus patients as adjunctive and alternative therapy. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011; 137(1):643–51.

CrossRef - Mohanraj K, Karthikeyan BS, Vivek-Ananth RP, Chand RPB, Aparna SR, Mangalapandi P. IMPPAT: A curated database of Indian Medicinal Plants, Phytochemistry And Therapeutics. Sci Rep. 2018; 8(1):4329.

CrossRef - Choudhury H, Pandey M, Hua CK, Mun CS, Jing JK, Kong L. An update on natural compounds in the remedy of diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. J Tradit Complement Med. 2018; 8(3):361–76.

CrossRef - Badole SL, Bodhankar SL. Glycine max (Soybean) Treatment for Diabetes. In Bioactive Food as Dietary Interventions for Diabetes. 2013; 77–82.

CrossRef - Kwon DY, Daily JW, Kim HJ, Park S. Antidiabetic effects of fermented soybean products on type 2 diabetes. Nutr Res. 2010; 30(1):1–13.

CrossRef - Sharifinejad N, Hooshyar M, Ramezankhah M, Shamsehkohan A, Saie R, Sahebjam M. An Update on the Anti-diabetic Functions of Genistein: A Soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) Isoflavone. Curr Tradit Med. 2024; 10(2): e070323214439.

CrossRef - Villegas R, Gao YT, Yang G, Li HL, Elasy TA, Zheng W. Legume and soy food intake and the incidence of type 2 diabetes in the Shanghai Women’s Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008; 87(1):162–7.

CrossRef - Ferreira LLG, Andricopulo AD. ADMET modeling approaches in drug discovery. Drug Discov Today. 2019; 24(5):1157–65.

CrossRef - Mohajan D, Mohajan HK. Obesity and Its Related Diseases: A New Escalating Alarming in Global Health. J Innov Med Res. 2023; 2(3):12–23.

CrossRef - Berghöfer A, Pischon T, Reinhold T, Apovian CM, Sharma AM, Willich SN. Obesity prevalence from a European perspective: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2008; 8(1):200.

CrossRef - Yahaya MAF, Bakar ARA, Stanslas J, Nordin N, Zainol M, Mehat MZ. Insights from molecular docking and molecular dynamics on the potential of vitexin as an antagonist candidate against lipopolysaccharide (LPS) for microglial activation in neuroinflammation. BMC Biotechnol. 2021; 21(1):38.

CrossRef - Ni B, Wang H, Khalaf HKS, Blay V, Houston DR. AutoDock-SS: AutoDock for Multiconformational Ligand-Based Virtual Screening. J Chem Inf Model. 2024; 64(9):3779–89.

CrossRef - Xiong G, Wu Z, Yi J, Fu L, Yang Z, Hsieh C. ADMETlab 2.0: an integrated online platform for accurate and comprehensive predictions of ADMET properties. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021; 49(W1):W5–14.

CrossRef - Mori H, Shichita T, Yu Q, Yoshida R, Hashimoto M, Okamoto F. Suppression of SOCS3 expression in the pancreatic β-cell leads to resistance to type 1 diabetes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007; 359(4):952–8.

CrossRef - Ansari P, Khan JT, Chowdhury S, Reberio AD, Kumar S, Seidel V. Plant-Based Diets and Phytochemicals in the Management of Diabetes Mellitus and Prevention of Its Complications: A Review. Nutrients. 2024; 16(21):3709.

CrossRef - Masson W, Lobo M, Siniawski D, Huerín M, Molinero G, Valéro R. Therapy with cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) inhibitors and diabetes risk. Diabetes Metab. 2018; 44(6):508–13.

CrossRef - Purnomo Y, Wibisono N, Triliana R. Molecular Docking Studies of Phytochemical substances of Soybean (Glycine max) seed and Ginger (Zingiber officinale) rhizome on Aldose Reductase and NADPH Oxidase-1 that plays a role in Diabetic complication. Res J Pharm Technol. 2025; 18(5):2095–100.

CrossRef - Patel, D. K. Therapeutic potential of a bioactive flavonoids glycitin from Glycine max: a review on medicinal importance, pharmacological activities and analytical aspects. Cur Trad Med. 2023; 9(2): 33-42.

CrossRef - Yang R, Trevillyan JM. c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathways in diabetes. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008; 40(12):2702–6.

CrossRef - Purnomo Y, Wibisono N, Triliana R. Molecular Docking Studies of Phytochemical substances of Soybean (Glycine max) seed and Ginger (Zingiber officinale) rhizome on Aldose Reductase and NADPH Oxidase-1 that plays a role in Diabetic complication. Res J Pharm Technol. 2025; 18(5):2095–100.

CrossRef - Bertrand AT, Brull A, Azibani F, Benarroch L, Chikhaoui K, Stewart CL. Lamin A/C Assembly Defects in LMNA-Congenital Muscular Dystrophy Is Responsible for the Increased Severity of the Disease Compared with Emery–Dreifuss Muscular Dystrophy. Cells. 2020; 9(4):844.

CrossRef - Purnomo Y, Taufiq M, Wijaya, Hakim R. Molecular Docking of Soybean (Glycine max) Seed and Ginger (Zingiber officinale) Rhizome Components as Anti-Diabetic Through Inhibition of Dipeptidyl Peptidase 4 (DPP-4) and Alpha-Glucosidase Enzymes:. Trop J Nat Prod Res. 2021; 5(10):1735–42.

CrossRef - Haidar S, Lackey S, Charette M, Yoosefzadeh-Najafabadi M, Gahagan AC, Hotte T, Belzile F, Rajcan I, Golshani A, Morrison MJ, Cober ER. Genome-wide analysis of cold imbibition stress in soybean, Glycine max. Front in Plant Sci. 2023;14:1-13.

CrossRef - Gai Y, Liu S, Zhang Z, Wei J, Wang H, Liu L, Bai Q, Qin Q, Zhao C, Zhang S, Xiang N. Integrative Approaches to Soybean Resilience, Productivity, and Utility: A Review of Genomics, Computational Modeling, and Economic Viability. Plants. 2025; 14(5): 671.

CrossRef - Damián-Medina K, Salinas-Moreno Y, Milenkovic D, Figueroa-Yáñez L, Marino-Marmolejo E, Higuera-Ciapara I. In silico analysis of antidiabetic potential of phenolic compounds from blue corn (Zea mays L.) and black bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Heliyon. 2020; 6(3), e03632.

CrossRef - Ramlal A, Bhat I, Nautiyal A, Baweja P, Mehta S, Kumar V. In silico analysis of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitory compounds obtained from soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.]. Front in Physiol, 2023, (14), 1-9.

CrossRef

Abbreviations

ADMET: Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion and Toxicity;

T1DM: Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus;

T2DM: Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus;

WHO: World Health Organization;

IMPPAT: Indian Medicinal Plants, Phytochemistry, and Therapeutics;

JNK1:C-Jun N-terminal Kinase 1 (JNK1);

CETP: Cholesteryl Ester Transfer Protein;

PPAR- γ:Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ;

RCSB: Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics;

NHBD: Number of H-Bond Donors;

BBB: Blood Brain Barrier

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.