Manuscript accepted on : 17-05-2025

Published online on: 27-05-2025

Plagiarism Check: Yes

Reviewed by: Dr. Sonam Sneha

Second Review by: Dr. Ranjit Ranbhor

Final Approval by: Dr. Amr Salah Morsy

Mamadou Toure1* , Kanvaly Dosso1

, Kanvaly Dosso1 , Doudjo Noufou Ouattara2,3

, Doudjo Noufou Ouattara2,3 , N’guetta Moïse Ehouman1

, N’guetta Moïse Ehouman1 and Seydou Tiho1

and Seydou Tiho1

1Laboratoire d’Ecologie et Développement Durable (LEDD), UFR Sciences de la Nature, Université Nangui ABROGOUA, Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire

2Laboratoire de Botanique et Valorisation de la Diversité Végétale, UFR Sciences de la Nature, Université Nangui ABROGOUA, Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire

3Centre Suisse de Recherches Scientifiques en Côte d’Ivoire (CSRS), Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire

Corresponding Author E-mail: tourexham@yahoo.fr

DOI : http://dx.doi.org/10.13005/bbra/3392

ABSTRACT: This study aims to transition the prevailing extensive cashew nut cultivation model into a more sustainable farming approach that enhances tree productivity. To achieve this, insect pest populations were surveyed across three orchard age categories: young orchards (0-5 years), intermediate orchards (5-10 years) and mature orchards (over 10 years), each covering an area of 1 hectare. For each age group, 5 orchards were selected, and in each orchard, an arrangement of 10 consecutive cashew trees chosen at random in the direction of the north-east diagonal was set up. Parasitic pressure parameters were then assessed and determined. A total of 70 insect pests divided into six orders were collected in all the orchards sampled. On average, 43.33% of the cashew seedlings analyses fell victim to insect attack, a proportion that proved higher in orchards aged 0-5 years, where 70% of trees were affected. These young orchards also showed the greatest abundance (32 individuals) and diversity (15 species) of pests. Overall, organ vulnerability was characterized by attack rates reaching 100% for trunks, 54.11% for branches and 8.7% for buds. In addition, a significant variation in parasite pressure was noted according to the different types of orchards sampled. However, orchards more than 10 years old showed significantly better agronomic performance (fruiting and production rates) than younger orchards (0-5 years and 5-10 years). Young orchards require adequate technical support, the lack of which often results in the neglect of pruning and coppicing operations on young plants, leading in particular to a significant accumulation of deadwood. Careful application of these compensatory measures will help increase both the volume and quality of floral resources, as well as increasing the presence of beneficial insects, thereby optimizing the agronomic yields of the various orchards.

KEYWORDS: Cashew tree; Côte d’Ivoire; Insect pests; Parasitic pressures

Download this article as:| Copy the following to cite this article: Toure M, Dosso K, Ouattara D. N, Ehouman N. G. M, Tiho S. Assessment of Insect Pest Pressure in Cashew Orchards (Anacardium occidentale L.) in Marahoué Region, Bouaflé, Côte d’Ivoire. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(2). |

| Copy the following to cite this URL: Toure M, Dosso K, Ouattara D. N, Ehouman N. G. M, Tiho S. Assessment of Insect Pest Pressure in Cashew Orchards (Anacardium occidentale L.) in Marahoué Region, Bouaflé, Côte d’Ivoire. Biotech Res Asia 2025;22(2). Available from: https://bit.ly/43hcNoL |

Introduction

The cashew tree (Anacardium occidentale L.) was introduced in northern Côte d’Ivoire in the early 1960s due to its rapid growth and hardiness, making it effective in combating deforestation, soil erosion, and bushfires.1,2 Initially considered a means of improving ecosystems, the cashew tree gradually gained significant economic importance through the commercialization of its fruit, the cashew nut.3,2

Over the past decade, cashew nut production in Côte d’Ivoire has experienced substantial growth, driven by several factors: favorable international market prices, the expansion of cultivated areas, and reforms initiated by the government from 2001 to structure the cashew sector.² As a result, Côte d’Ivoire has become the world’s leading producer and exporter of raw cashew nuts, accounting for nearly 25% of global production and about 50% of global supply.4 In 2016, the sector’s economic contribution was estimated at approximately USD 700 million, ranking cashew nuts as the country’s third-largest export product, after cocoa and petroleum products. Producer revenues reached USD 500 million.4 Thanks to this potential, cashew cultivation has become a major source of income in producing areas (North, East, and Center), as well as a powerful driver of job creation and improved living conditions.5

However, this economically important crop is threatened by numerous challenges, particularly phytosanitary issues, which significantly hinder its yield and sustainability. Indeed, the development of the sector has largely occurred independently, without sufficient support from the government or assistance from research and agricultural extension services.6,7 This has led to the use of unimproved seeds, the persistence of traditional farming techniques, the application of pesticides whose environmental impacts remain poorly assessed, and, above all, the ongoing prevalence of major phytosanitary problems particularly insect pest infestations.8,9 These pests are estimated to cause production losses ranging from 60% to 80% in the absence of effective control measures.10 It is therefore essential to better assess the health status of cashew orchards in order to propose more effective and sustainable pest management methods, especially to prevent the development of resistance in pest populations.

To sustain its position as the leading global producer and exporter of cashew nuts, Côte d’Ivoire faces a number of challenges, in particular the need to increase production by adopting sustainable agronomic methods that reduce land pressure. This study objective to evaluate the impact of insect pests on the agronomic performance of cashew seedlings. The overall aim is to transform the currently extensive cashew production model towards sustainable cashew cultivation by increasing tree productivity. Specifically, the aim is to: (i) analyze insect pest populations, (ii) diagnose the health status of orchards and (iii) establish a correlation between insect pest populations and the agronomic performance of cashew seedlings.

Materials and Methods

Study site

This research was conducted in the Marahoué region of West-Central Côte d’Ivoire, recognized as one of the country’s key cashew-producing areas. Situated approximately 60 km from Yamoussoukro, the political capital, and 310 km from Abidjan, the economic capital, this region lies at the transition between forest and savannah ecosystems. Annual cashew nut production in the area is estimated between 10000 and 20000 tons.

Furthermore, the village of Attossé (Fig. 1) was chosen as the host site for the study because it represents one of the areas in the region with a large area under cashew cultivation but characterized by low productivity per tree.

|

Figure 1: Study site |

Choice of plots and sampling device

This study is based on the selection of three types of cashew orchards classified by age groups: young (0-5 years), intermediate (5-10 years), and mature (over 10 years), each with an area of one hectare. For each age group, five orchards were selected, for a total of 15 orchards. In each orchard, ten cashew trees were randomly selected to serve as observation units.

The random selection of trees was carried out using a diagonal transect method oriented from the northeast to the southwest of the orchard. A random number generator (using the RAND function in Microsoft Excel) was used to determine the starting point along the transect. From this initial point, trees were selected consecutively without skipping, following the alignment of the transect until ten trees were reached. This approach helps minimize selection bias while ensuring spatial representativeness of the sampled trees within each orchard (Fig. 2).

|

Figure 2: Sampling device |

Capture of insect pests

Insect pests, distinguished by their tendency to remain stationary while feeding on cashew trees9, were collected using entomological forceps. Specimens were preserved in labeled vials 70% ethanol for further analysis. The technique consisted in carefully inspecting trunks, branches, leaves, inflorescences, flowers and fruit to capture pests. Each tree produced 4 samples per sampling hour, and 12 samples per day. The bottles containing the insects were taken to the laboratory for enumeration and identification at the taxonomic levels of order and family. The recognition key of10, the collection identification key of11 and the dichotomous identification key were used to recognize the taxonomic units, order and family, into which the collected insects were classified.

Assessing pest pressure

The technique consisted of carefully inspecting the trunk, branches, leaves, inflorescences, flowers, and fruits to detect areas of insect-related infections.12,9 Thus, data on pest incidence (presence and/or absence) were obtained by counting the damaged areas (holes with fresh sap oozing, points and/or zones of tunneling, desiccation of vegetative and floral buds, scraped leaves, and scraped and/or punctured fruits). Based on the architecture of the cashew trees, the categories of vulnerable organs (trunk, branch, bud, and fruits) for each tree were identified13 and counted within each sampling unit. Next, the severity (S) of infestations was assessed according to previously established methods by characterizing the infected areas on each tree using a grading system.9 Grade “zero” or S0 indicated attacks or infection zones that were healed or completely dry, showing no active pest activity on the host organs. Grade “one” or S1 referred to attacks or infections without harmful effects, such as sap oozing, completely cut branches, and desiccated buds and fruits. Grade “two” or S2 indicated attacks or infections with harmful effects, including sap flow, completely severed branches, and drying of buds and fruits.

Determination of parasitic pressure parameters

Proportion of cashew trees attacked

The proportion of cashew trees attacked by insects (Pa) was determined using the following formula.12:

Pa = (Nm/N) x 100

Where Nm: number of cashew trees attacked by insects; N: number of trees in the device.

These proportions are classified as: Very low (0% < Pa ≤ 25%), Low (25% < Pa < 50%), High (50% < Pa ≤ 75%) and Very High (75% < Pa ≤ 100%) according to.14

Organ vulnerability

Organ vulnerability (Vo) represents the proportion of each organ category under attack. It is determined using the following formula.12:

Vo = (𝚺Oi/Nm) x 100

Where 𝚺Oi: sum of organs attacked by category (trunk, branch, bud and fruit); Nm: number of cashew trees attacked by insects.

According to14, the proportions are classified into the following categories: Very Low (0% < Vo ≤ 25%), Low (25% < Vo ≤ 50%), High (50% < Vo ≤ 75%) and Very High (75% < Vo ≤ 100%).

Severity indices

The severity index (Is) represents the proportion of cashew trees suffering severe attacks (negatively affecting yields). It is determined using the following formula.12:

Is = (𝚺Ni.Si/Na) x 100

Where Ni: number of trees attacked by grade; Si: grade types; Na: total number of pest attacks.

Not hazardous (Is < 15%), Very Weak (15% < Is ≤ 25 %), Weak (25% < Is ≤ 50%), Strong (50% < Is ≤ 75%) and Very Strong (75% < Is ≤ 100%) are classifications given by.14.

Data analysis

The observed species richness (Sobs) was obtained by counting insect species after identification. The software EstimateS version 9.1.0 was used to calculate estimated species richness (Chao 2), Simpson’s diversity index, and its evenness. These indices were chosen because they provide complementary information: Chao 2 estimates undetected species to address sampling limitations, Simpson’s index measures dominance and diversity, while evenness reflects the uniformity of species distribution. To explore relationships between the studied parameters (insect activity, pest pressure, and agronomic performance), Pearson correlation analysis was performed using PAST software version 3.0.9, with a significance threshold of 0.05. Prior to this, Levene’s test was applied to assess the homogeneity of variances, which is crucial for determining whether parametric or non-parametric tests are appropriate. In cases where data followed a normal distribution, Tukey’s pairwise test or one-way repeated-measures ANOVA was used for multiple comparisons. If the distribution was non-normal, non-parametric tests such as the Kruskal-Wallis test or the Mann-Whitney U test were applied. Additionally, all parameters measured in the orchards were compared to those of reference cashew trees selected according to15, which are recognized as high-yielding individuals.

Results

Insect pest population

In all the orchards sampled, 70 insect pests in 6 orders (Hemiptera, Coleoptera, Orthoptera, Lepidoptera, Odonata and Diptera) were collected. Diptera (15±4.06 individuals) and Orthoptera (15±3.23 individuals) showed the highest abundances, followed by Coleoptera (13±4.02 individuals), Lepidoptera (12±1.97 individuals), Hemiptera (11±2.00 individuals) and Odonata (4±0.03 individuals) (Table 1). For the distribution of these pests according to the different types of orchards, the highest abundances were observed in orchards of 0-5 years (32±6.41 individuals) followed by orchards of 5-10 years and over 10, which presented 21±4.85 and 17±1.28 individuals respectively (Mann Whitney U test, p < 0.05). The same is true for specific diversity, with 15 species for orchards aged 0-5 years, followed by orchards aged 5-10 years and over 10 years, which showed 7 and 5 pest species respectively (Mann Whitney U test, p < 0.05). However, a total of 15 pest species were collected during this study (Table 1).

Table 1: Insect pests collected in orchards

| Order of insects | Orchards 0-5 years | Orchards 5-10 years | Orchards over 10 years | Total | Probability |

| Hemiptera | 8±0.54 | 1±0.07 | 2±0.02 | 11±2.00 | – |

| Coleoptera | 9±0.92 | 4±0.26 | 0±0.00 | 13±4.02 | – |

| Orthoptera | 6±0.36 | 7±0.41 | 2±0.05 | 15±3.23 | – |

| Lepidoptera | 3±0.07 | 2±0.13 | 7±1.16 | 12±1.97 | – |

| Odonata | 1±0.01 | 2±0.08 | 1±0.01 | 4±0.03 | – |

| Diptera | 5±0.15 | 5±0.21 | 5±0.85 | 15±4.06 | – |

| Abundance (individuals) | 32±6.41a | 21±4.85b | 17±1.28b | 70±8.12 | 0.02 |

| Specific richness | 15a | 7b | 5b | 15 | 0.037 |

The values with different letters on the same line are substantially different (Mann-Whitney U test, p < 0.05)

Orchard health

Attack rate

In all, 43.33% of the cashew plants sampled had been attacked by insects. Attacks were highest in orchards aged 0-5 years (70±5.24%), followed by those aged 5-10 years (40±2.45%) and those aged 10 years and over (20±1.87%). Thus, the scale of attack assessment was characterized by a high rating in orchards 0-5 years, a medium rating in orchards 5-10 years and a low rating in orchards over 10 years (Table 2).

Table 2: Proportions of cashew trees attacked by insect pests

| Orchards 0-5 years | Orchards 5-10 years | Orchards over 10 years | Means | |

| Proportion of cashew trees attacked (%) | 70±5.24 | 40±2.45 | 20±1.87 | 43.33±4.56 |

| Assessment | High | Medium | Low |

Organ vulnerability

In the orchards sampled, 100±0.50% of trunks, 54.11±0.35% of branches and buds and 8.7±0.03% of fruit were affected. According to the scale of attack, trunks were very vulnerable to insect pests, followed by branches and buds, which were vulnerable, and fruits, which were not very vulnerable. The distribution of attacks according to the types of orchards sampled showed that they were most significant in 0-5 years orchards (100±0.50% trunks, branches and buds, 17.6±0.06% fruit), followed by orchards 5-10 years (100±0.50% trunks, 62.35±0.23% branches and buds, 6.4±0.02% fruit) and orchards over 10 years (100±0.50% trunks, 0% branches and buds, 2.1±0.01% fruit) (Table 3).

Table 3: Proportions of organs attacked by insect pests

| Attacked organs | Orchards 0-5 years | Orchards 5-10 years | Orchards over 10 years | Means | Assessment | ||

|

Vulnerability |

Trunks (%) | 100±0.50 | 100±0.50 | 100±0.50 | 100±0.50 | Very strong | |

| Branches (%) | 100±0.50 | 62.35±0.23 | 0±0.00 | 54.11±0.35 | Strong | ||

| Buds (%) | 100±0.50 | 62.35±0.23 | 0±0.00 | 54.11±0.35 | Strong | ||

| Fruit (%) | 17.6±0.06 | 6.4±0.02 | 2.1±0.01 | 8.7±0.03 | Weak | ||

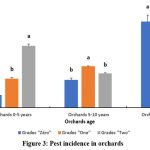

Attack severity index

A significant variation in parasite incidence was recorded, depending on the different types of orchards sampled. The type ”Zero” grades were significantly higher in orchards over 10 years (82.8±6.34 attacks), followed by orchards 5-10 years (26.78±1.82 attacks) and orchards 0-5 years (12.3±0.08 attacks) (Mann Whitney U test, p < 0.05). The types ”One” grades were significantly higher in 5-10 years orchards (40.1±1.52 attacks), followed by 0-5 years orchards (28.1±0.93 attacks) and orchards over 10 years (17.3±0.09 attacks) (Mann Whitney U test, p < 0.05). The types ”Two” grades were significantly higher in orchards 0-5 years (59.6±1.74 attacks), followed by orchards 5-10 years (33±0.58 attacks) and orchards over 10 years (12.3±0.12 attacks) (Mann Whitney U test, p < 0.05). Pest incidence was highest in orchards 0-5 years, followed by orchards 5-10 years and orchards over 10 years (Fig. 3). According to the rating scale, attacks were very severe in 0-5 years orchards, characterized by 66.75±1.93% of attacks, and slightly severe in 5-10 years orchards, characterized by 21.88±0.25% of attacks. On the other hand, in orchards over 10 years old, characterized by 11.35%±0.09, attacks were less harmful to yields.

|

Figure 3: Pest incidence in orchards |

Based on the grades, the proportions with different letter designations were significantly different (Mann-Whitney U test, p < 0.05)

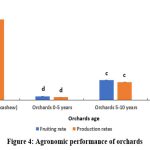

Agronomic performance of cashew orchards

The orchards over 10 years showed a fruiting rate of 28.36±0.68% and a production rate of 28.1±0.54% of flowers. The orchards over 10 years old showed a fruiting rate of 28.36±0.68% and a production rate of 28.1±0.54% of flowers. They were followed by 5-10 years orchards which showed a fruiting rate of 15.32±0.12% and a production rate of 13.82±0.07% of flowers. Finally, the 0-5 years orchards recorded a fruiting rate of 2.89±0.02% and a flower production rate of 2.34±0.01% (Fig. 4). The number of flowers pollinated by bees and the productivity of these orchards were significantly higher in orchards over 10 years, followed by orchards 5-10 years and orchards 0-5 years (Mann Whitney U test, p < 0.05).

Overall, orchards over 10 years old showed significantly higher agronomic performance (fruiting and production rates) than 5-10 years and 0-5 years orchards (Mann Whitney U test, p < 0.05). All three orchard varieties, however, displayed a significant yield difference when compared to the control (Mann Whitney U test, p < 0.05).

|

Figure 4: Agronomic performance of orchards |

The proportions across orchards, denoted by different letters, were significantly different (Mann-Whitney U test, p < 0.05)

Relationship between insect activity, tree health and agronomic performance

There was a substantial and positive correlation between parasite incidences and pest activity (r = 0.89; p < 0.05). Pest activity and pest incidence, on the other hand, were substantially and adversely linked with fruit set and fruit quality (r = -0.66, -0.58, -0.58 and -0.61; p < 0.05, p < 0.05, p < 0.05 and p < 0.05 correspondingly) (Table 4).

Table 4: Correlation between pest activity and agronomic performance

| Pearson correlation coefficient(r > 0.5; p < 0.05)

|

Pest activity | Parasitic impacts | Fructification | Fruit quality |

| Pest activity | – | |||

| Parasitic impacts | 0.89 | – | ||

| Fructification | -0.66 | -0.58 | – | |

| Fruit quality | -0.58 | -0.61 | 0.17 | – |

Discussion

Across all sampled cashew orchards, a total of 70 insect pests belonging to six taxonomic orders were collected. These pests were more abundant and diverse in the youngest orchards (0-5 years old). This observation may reflect a lack of appropriate technical management in young plantations, notably due to the absence of regular pruning and thinning, as well as the accumulation of dead wood from initial land preparation. Such debris provides ideal sites for pest oviposition and larval development.16-18

In addition to poor management practices, agronomic strategies commonly used in these young orchards could also contribute to pest proliferation. For instance, the open canopy structure is often associated with intercropping systems involving food crops such as oil palm and banana, which support farmer livelihoods before cashew production becomes profitable. However, when poorly managed, these systems may inadvertently promote pest activity by enhancing food availability and disrupting ecological balances.11

Beyond these immediate factors, an agroecological lens reveals deeper underlying causes of pest outbreaks. One key factor is soil health: nutrient-poor or unbalanced soils can induce physiological stress in plants, making them more vulnerable to pest attacks.19 Similarly, microclimatic conditions in young orchards often characterized by higher temperatures and humidity can further promote pest development and reproduction.20 Moreover, the reduction in natural enemies, which may result from low plant diversity and farming practices that do not favor biodiversity, limits the natural regulation of pest populations.21 Finally, the genetic makeup of the planting material plays a crucial role: the widespread use of low-resistance or genetically uniform varieties increases susceptibility to infestation.20

These biotic and abiotic vulnerabilities are reflected in field observations. Compared with orchards aged 5-10 years and those over 10 years, the youngest orchards (0-5 years) showed higher pest infestation rates, with a large number of organs reaching severity grade S2. This pattern aligns with the higher pest abundance and diversity recorded in these orchards. Two hypotheses may explain this phenomenon: first, the persistence of dead wood likely facilitates the rapid spread of infestations22; second, as cashew cultivation is relatively recent in this former cocoa-producing area23, residual pest populations and ecological legacies from previous cropping systems may continue to influence pest dynamics across orchards.

In contrast, plants from older orchards (over 10 years) generally displayed better agronomic performance. This suggests that the poor health status of young orchards may negatively impact both the quantity and quality of floral resources, as well as populations of beneficial insects such as bees and ants, which contribute to pest control and organ development.15,24 Furthermore, the accumulation of dead leaves in mature orchards may enrich soil fertility, thereby improving nectar and pollen quality. These improved floral resources could enhance pollinator activity, particularly that of bees, leading to higher plant productivity.24,25

Nonetheless, it is important to note that all three orchard age classes showed lower agronomic performance compared with high-yielding control trees. This discrepancy could be attributed to suboptimal agronomic practices, including the use of wild, heterogeneous seeds as planting material. Additionally, the widespread use of unregulated pesticides may adversely affect floral resources and pollinator populations, as well as beneficial insects involved in biological control, ultimately compromising overall orchard performance.8

Conclusion

In the Marahoué region, a total of 70 insect pest species, distributed across six taxonomic orders, were identified in the orchards surveyed. The greatest diversity and abundance were observed in the youngest orchards (0-5 years), which also exhibited the most severe infestations. These young orchards presented a high number of vulnerable plant organs showing marked levels of damage, indicating intense pest pressure. In contrast, older orchards (over 10 years) showed comparatively better agronomic performance, likely due to improved soil structure, increased ecological stability, and the progressive establishment of beneficial insect populations. Nevertheless, all orchards regardless of age demonstrated lower agronomic performance than reference high-yielding cashew plantations.

To optimize orchard productivity, special attention must be given to young plantations, which often suffer from insufficient technical support. This is particularly evident in the lack of systematic pruning, the accumulation of dead wood, and several biotic and abiotic factors which, from an agroecological perspective, may also contribute to increased pest pressure, thereby promoting the proliferation of insect pests. The implementation of appropriate management practices including regular pruning, debris removal, and ecological intensification can enhance floral resource availability and attract beneficial insect species. These improvements are essential for strengthening plant health and boosting the agronomic performance of cashew orchards across the region.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the NGO “Cultivating New Frontiers in Agriculture (CNFA)”, whose PRO-CASHEW program enabled fieldwork to be carried out in conjunction with the COVIMA cooperative in Bouaflé.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding sources

There are no funding sources.

Ethics approval statement

The study does not involve an experiment on humans and animals. No Ethical approval was conducted.

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not involve human participants, and therefore, informed consent was not required.

Clinical Trial Registration

This research does not involve any clinical trials.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources –

Not Applicable

Author Contributions

Mamadou TOURE: Conceptualization, Writing original draft preparation;

Kanvaly DOSSO: Conceptualization, Methodology;

Doudjo Noufou OUATTARA: Data collection, Analysis;

N’guetta Moise EHOUMAN: Data collection, Analysis;

Seydou TIHO: Supervision and review and editing.

References

- Basset TJ, Koné M, Pavlovic NR. Power relations and upgrading in the cashew value chain of Côte d’Ivoire. Dev. Chang. 2018;49(5):1223-1247. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12400.

CrossRef - Soro D, Dornier M, Abreu F, Assidjo E, Yao B, Reynes M. The cashew (Anacardium occidentale) industry in Côte d’Ivoire: analysis and prospects for development. Fruits. 2011;66(4):237-245. https://doi.org/10.1051/fruits/2011031.

CrossRef - Ndiaye A. Structuration professionnelle de la filière anacarde : une contribution durable à la paix-Côte d’Ivoire [Epertly organizing the cashew nut industry : a long-term way to promote peace in Côte d’Ivoire]. Rapport RONGEAD/IFCI. 2008:20. 24/Juillet 2008. https://www.nitidae.org/ files/ 33c298be/evaluationanacardeci.pdf.

- Bassett T. Le boom de l’anacarde dans le bassin cotonnier du Nord ivoirien : Structures de marché et prix à la production [The Cashew Boom in the Cotton Bassin of Northern Ivory Coast : Market Structures and Production Prices]. Afrique contemporaine. 2017;263-264(3):59-83. https://doi.org/10.3917/afco.263.0059.

CrossRef - Sinan A, Abou NK. Impacts socio-économiques de la culture de l’anacarde dans la Sous-préfecture d’Odienné (Côte d’Ivoire) [Cashew nut cultivation’s socioeconomic effects in the Odienné (Côte d’Ivoire)]. esj journal. 2016;12(32):369. https://doi.org/10.19044/esj.2016.v12n32p369.

CrossRef - Yao SK, James HK, Yeboué-Kouamé BY, Joseph S, Assanvo JE. Study of pesticides use condition in cashew production in Côte d’Ivoire. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Sci. 2020;12:1-9. https://doi.org/10.5897/JTEHS2018.0427.

- Cisse S, Coulibaly TJH, Coulibaly N et al. Assessment of the natural landscape changes due to cashew plantations in the department of Niakaramandougou (North of Côte d’Ivoire). Journal of Agricultural Chemistry and Environment. 2021;10:196-212. https://doi.org/10.4236/jacen.2021.102013.

CrossRef - Djaha AJB, N’Da HA, Koffi KE, Adopo A, Ake S. Diversité morphologique des accessions d’anacardier (Anacardium occidentale L.) introduits en Côte d’Ivoire [Morphological diversity of cashew (Anacardium occidentale L.) accessions introduced in Côte d’Ivoire]. Rev. Ivoir. Sci. Technol. 2014;23(2014):244-258. https://revist.net/REVIST_23/REVIST_23_16.pdf.

- Agboton C, Onzo A, Ouessou FI, Goergen G, Vidal S, Tamo M. Insect fauna associated with Anacardium occidentale (Sapindales: Anacardiaceae) in Benin, West vAfrica. J Insect Sci. 2014;1(14):229. https://doi.org/10.1093/jisesa/ieu091.

CrossRef - Delvare G, Aberlenc H-P. Les insectes d’Afrique et d’Amérique tropicale : Clés pour la reconnaissance des familles [insects of Africa and tropical America : Keys to family recognition] (Editions Quae). 1989:305.

- Roth V, Brown W. Arthropoda: Insecta (Insects). Chapter 22. In : Brusca RC (ed) Common intertidal invertebrates of the Gulf of California. University of Arizona Press, Tucson, Arizona. 1980:326-346. https://www.academia.edu/40498769/Invertebrates_Brusca.

- Cadoso JE, Santos AA, Rossetti AG, Vidal JC. Relationship between incidence and severity of cashew gummosis in semiarid North-eastern Brazil. Plant Pathol. 2024;53(3):363-367. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0032-0862.2004.01007.x.

CrossRef - International Board for Plant Genetic Resources (IBPGR). IBPGR Advisory committee On In Vitro Storage. Report of the third Meeting Held In Valencia, Spain 4-6 June1986/ INTERNATIONAL BOARD FOR PLANT GENETIC RESOURCES. 1986:30. https://www.kikp-pertanian.id/pustaka/opac/detail-opac?id=4785.

- Groth JV, Ozmon EA, Bush RH. Repeatability and Relationship of Incidence and severity Measures of Scab of Wheat Caused by Fusarium graminearum in Inoculated Nurseries. Plant Dis. 1999;83(11):1033-1038. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS.1999.83.11.1033.

CrossRef - Silué D, Yéo K, Soro NA et al. Assessing the influences of bee’s (Hymnoptera: Apidae) floral preference on cashew (Anacardiaceae) agronomics performances in Côte d’Ivoire. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2022;52(2)9474-9494. https://doi.org/10.35759/JAnmPISci.v52-2.5.

- Anato FM, Wargui RB, Sinzogan AAC et al. Reducing losses inflicted by insect pests on cashew, using weaver ants as a biological control agent. Agricultural and Forest Entomology. 2015;17(3):285-291. https://doi.org/10.1111/afe.12105.

CrossRef - Onzo A, Biaou JT, Agboton C. Efficacité du ramassage et du brûlage systématiques des bois morts dans la lutte contre le foreur de bois, Apate terebrans, dans les anacarderaies du Nord Bénin [Effectiveness of systematic collection and burning of dead wood to control the wood borer, Apate terebrans, in cashew groves in Northern Benin]. J. Appl. Biosci. 2018;121:12168-12180. https://dx.doi.org/10.4314/jab.v121i1.7.

CrossRef - Adeniyi DO, Animasaun DA, Abdulrahman AA, Olorunmaiye KS, Olahan GS, Adeji OA. Integrate system for cashew disease management end yield. Cameroon Journal of Experimental biology. 2019;13(1):40-46. https://dx.doi.org/10.4314/cajeb.vol13i1.6.

CrossRef - Altieri MA, Nicholls CI, Dinelli G et al. Towards an agroecological approach to crop health: reducing pest incidence through synergies between plant diversity and soil microbial ecology. Research in Agroecology. 2024;8(2):101-115. https://www.fao.org/agroecology/database/detail/en/c/1710998/.

CrossRef - Amani K, Coulibaly KRL, Tondoh EJ et al. Weather-Informed Recommendations for Pest and Disease Management in the Cashew Production Zone of Côte d’Ivoire. Sustainability. 2023;15(15):11877. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511877.

CrossRef

- Coulibaly A, Adiko YYO, Tra Bi CS, Minhibo MY, Djaha J-BA, Fondio L. Évaluation des techniques de surgreffage dans la lutte contre les termites (Isoptera: Termitidae) dans les vergers d’anacardiers dans le Nord de la Côte d’Ivoire. Agronomie Africaine. 2024;36(1):31-42. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/aga/article/view/275856.

- Olatu MI, du Plessis H, Seguni ZS, Maniania NK. Efficacy of the African weaver ant Oecophylla longinoda (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in the control of Helopeltis spp. (Hemiptera: Miridae) and Pseudotheraptud wayi (Hemiptera; Coreidae) in cashew crop in Tanzania. Pest Mang Sci. 2013;69(8):911-8. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.3451.

CrossRef - Ruf F, Uribe LE, Gboko K, Carimentrand A. Des certifications inutiles ? Les relations asymétriques entre coopératives, labels et cacaoculteurs en Côte d’Ivoire [Useless certifications ? Asymmetrical relations between cooperatives, label and cocoa famers in Côte d’Ivoire]. Revue internationale des études du développement. 2019;240(4),31-61. https://doi.org/10.3917/ried.240.0031.

CrossRef - Coulibaly D, Koné M, Tuo Y, Soro K, Koua KH. Impact of Beekeeping on the Wild Bee Diversity in Northern Ivory Coast (West Africa). Research in Ecology. 2024;6(1):6-13. https://doi.org/10.30564/ re.v6i1.6023.

CrossRef - Tuo Y, Coulibaly D, Coulibaly T, Bakayoko S, Koua KH. Role of two agrosystems (mango and cashew trees orchards) in bees’ activity increasing within beehives in Korhogo, Northern Ivory Cost (West Africa). Entomol. Appl. Sci. Lett. 2019;6(3):48-54. https://easletters.com/issue/vol-6-issue-3-2019.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.